List of leaders of the Soviet Union

| Leader of the Soviet Union | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Residence | Grand Kremlin Palace, Moscow |

| Appointer | A leader would not be able to rule, or hold on to power, without support in the Politburo, Central Committee and/or the Secretariat of the Central Committee |

| Formation | 30 December 1922 (founding of the Soviet Union) |

| First holder |

Vladimir Lenin (as Premier) |

| Final holder |

Mikhail Gorbachev (as President) |

| Abolished |

25 December 1991 (end of communist rule) 26 December 1991 (end of the Soviet Union) |

Under the 1977 Constitution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the Chairman of the Council of Ministers was the head of government[1] and the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet was the head of state.[2] The office of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers was the equivalent to a First World Prime Minister,[1] while the office of the Chairman of the Presidium was equivalent to the office of the President.[2] In the Soviet Union's seventy-year history there was no official leader of the Soviet Union offices but a Soviet leader usually led the country through the office of the Premier and/or the office of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). In the ideology of Vladimir Lenin the head of the Soviet state was a collegiate body of the vanguard party (see What Is to Be Done?).

Following Joseph Stalin's consolidation of power in the 1920s[3] the post of the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party became synonymous with 'Leader of the Soviet Union'[4] because the post controlled both the CPSU and the Soviet Government.[3] The post of the General Secretary was abolished under Stalin and later re-established by Nikita Khrushchev under the name of First Secretary; in 1966 Leonid Brezhnev reverted the office title to its former name. Being the head of the communist party,[5] the office of the General Secretary was the highest in the Soviet Union until 1990.[6] The post of General Secretary lacked clear guidelines of succession, so after the death or removal of a Soviet leader, the successor usually needed the support of the Politburo, the Central Committee, or another government or party apparatus to both take and stay in power. The President of the Soviet Union, an office created in March 1990, replaced the General Secretary as the highest Soviet political office.[7]

Contemporaneously to establishment of the office of the President, representatives of the Congress of People's Deputies voted to remove Article 6 from the Soviet constitution which stated that the Soviet Union was a one-party state controlled by the Communist Party which, in turn, played the leading role in society. This vote weakened the Party and its hegemony over the Soviet Union and its people.[8] Upon death, resignation, or removal from office of an incumbent President, the Vice President of the Soviet Union would assume the office, though the Soviet Union collapsed before this was actually tested.[9] After the failed August Coup the Vice President was replaced by an elected member of the State Council of the Soviet Union.[10]

Summary

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Soviet Union |

|

Judiciary |

Vladimir Lenin was voted the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR (Sovnarkom) on 30 December 1922 by the Congress of Soviets.[11] His health, at the age of 53, declined from effects of two bullet wounds, later aggravated by three strokes which culminated with his death in 1924.[12] Irrespective of his health status in his final days, Lenin was already losing much of his power to Stalin.[13] Alexei Rykov succeeded Lenin as Chairman of the Sovnarkom, and although he was de jure the most powerful person in the country, the Politburo of the Communist Party began to overshadow the Sovnarkom in the mid-1920s. By the end of the decade, Rykov merely rubber stamped the decisions predetermined by Stalin and the Politburo.[14]

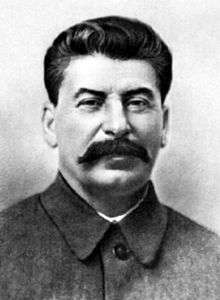

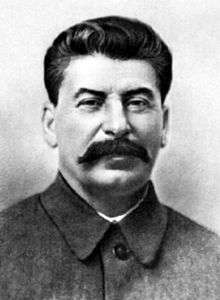

Stalin's early policies pushed for rapid industrialisation, nationalisation of private industry[15] and the collectivisation of private plots created under Lenin's New Economic Policy.[16] As leader of the Politburo, Stalin consolidated near-absolute power by 1938 after the Great Purge, a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution.[17] Nazi German troops invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941,[18] but were repulsed by the Soviets in December. On Stalin's orders, the USSR launched a counter-attack on Nazi Germany.[19] Stalin died in March 1953,[20] his death triggered a power struggle in which Nikita Khrushchev after several years emerged victorious against Georgy Malenkov.[21]

Khrushchev denounced Stalin on two occasions: in 1956 and 1962. His policy of de-Stalinisation earned him many enemies within the party, especially from old Stalinist appointees. Many saw this approach as destructive and destabilising. A group known as Anti-Party Group tried, but failed, to oust Khrushchev from office in 1957.[22] As Khrushchev grew older, his erratic behavior became worse, usually making decisions without discussing or confirming them with the Politburo.[23] Leonid Brezhnev, a close companion of Khrushchev, was elected First Secretary the same day of Khrushchev's removal from power; Alexei Kosygin became the new Premier and Anastas Mikoyan kept his office as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. In 1965, on the orders of the Politburo, Mikoyan was forced to retire; Nikolai Podgorny took over the office of Chairman of the Presidium.[24] The USSR in the post-Khrushchev 1960s was governed by a collective leadership.[25] Henry A. Kissinger, the American National Security Advisor, mistakenly believed that Kosygin was the 'Leader of the Soviet Union and that he was at the helm of 'Soviet foreign policy' because he represented the Soviet Union at the 1967 Glassboro Summit Conference.[26] The "Era of Stagnation", a derogatory term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, was a period marked by low socio-economic efficiency in the country and a gerontocracy ruling the country.[27] Yuri Andropov succeeded Brezhnev in his post as General Secretary in 1982. He was 68 years old at the time. In 1983 Andropov was hospitalised, and rarely met up at work to chair the politburo meetings due to his declining health; Nikolai Tikhonov usually chaired the meetings in his place.[28] Following Andropov's death 15 months after his appointment, an even older leader, 72 year old Konstantin Chernenko was elected to the General Secretariat. His rule lasted for little more than a year until his death 13 months later on 10 March 1985.[29]

Mikhail Gorbachev was elected to the General Secretariat by the Politburo on 11 March 1985.[30] He was 54 years old at the time. In May 1985, Gorbachev publicly admitted the slowing down of the economic development and inadequate living standards, being the first Soviet leader to do so, and began a series of fundamental reforms. From 1986 to around 1988 he dismantled central planning, allowed state enterprises to set their own outputs, enabled private investment in businesses not previously permitted to be privately owned, and allowed foreign investment, among other measures. He also opened up the management of and decision-making within the Soviet Union, and allowed greater public discussion and criticism, along with a warming of relationships with the West. These twin policies were known as perestroika (literally meaning "reconstruction", but varies) and glasnost ("openness" and "transparency") respectively.[31] The dismantling of the principal defining features of communism in 1988 and 1989 in the Soviet Union led to the unintended consequence of the Soviet Union breaking up after the failed August Coup of 1991 led by Gennady Yanayev,[32] and its conversion to a federation of 15 independent states.

List of leaders

The following list includes only those persons who were able to gather enough support from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the government, or one of these to lead the Soviet Union. † denotes leaders who died in office.

| Name (Birth–Death) |

Portrait | Supreme Rule | Congress | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924)[33] |

|

30 December 1922[33] ↓ 21 January 1924†[13] |

11th–12th Congress | Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) and informal leader of the Bolsheviks since their inception.[33] Was leader of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) from 1917 and leader of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) from 1922 until his death.[34] |

| Joseph Stalin (1878–1953)[13] |

|

21 January 1924[13] ↓ 5 March 1953†[35] |

13th–19th Congress | General Secretary from 3 April 1922 until 1934, when he resigned from office; the post of General Secretary itself was abolished in October 1952.[36] Stalin served as Premier from 6 May 1941 until his death on 5 March 1953.[35] He also held the post of the Minister of Defence from 19 July 1941 until 3 March 1947 and Chairman of the State Defense Committee during the Great Patriotic War[37] and became the only officer to hold the office of People's Commissariat of Nationalities from 1921–1923.[38] |

| Georgy Malenkov (1902–1988)[39] |

|

5 March 1953[39][40] ↓ 8 February 1955[41] |

19th Congress | Succeeded to all of Stalin's titles, but was forced to resign most of them within a month.[42] Malenkov, through the office of Premier, was locked in a power struggle against Khrushchev.[43] |

| Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971)[44] |

|

8 February 1955[44] ↓ 14 October 1964[45] |

20th–22nd Congress | Served as the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (from September 1953) and Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 27 March 1958 to 14 October 1964. While vacationing in Abkhazia, Khrushchev was called by Leonid Brezhnev to return to Moscow for a special meeting of the Presidium, to be held on 13 October 1964. There, at the most fiery session since the so-called "anti-party group" crisis of 1957, he was fired from all his posts. He was largely left in peace in retirement, but was made a "non-person" to the extent that his name was removed even from the thirty-volume Soviet Encyclopedia.[46] He died in 1971. He was seen overseas as a reformer of a "petrified structure" [47] and described his main contribution as removing the fear that Stalin had brought,[48] but many of his reforms were later reversed. |

| Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982)[45] |

.jpg) |

14 October 1964[45] ↓ 10 November 1982†[49] |

23rd–26th Congress | Served as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, was later renamed General Secretary,[23] and was co-equal with premier Alexei Kosygin until the 1970s. To consolidate his power he later assumed the title of Chairman of the Presidium.[24] |

| Yuri Andropov (1914–1984)[50] |

|

12 November 1982[50] ↓ 9 February 1984†[51] |

— | General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party[26] and Chairman of the Presidium from 16 June 1983 until 9 February 1984.[52] |

| Konstantin Chernenko (1911–1985)[53] |

|

13 February 1984[53] ↓ 10 March 1985†[23] |

— | General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party[54] and Chairman of the Presidium from 11 April 1984 to 10 March 1985.[55] |

| Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–)[56] |

|

11 March 1985[23] ↓ 19 August 1991[57] |

27th–28th Congress | Served as General Secretary from 11 March 1985,[55] and resigned on 24 August 1991,[58] Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1 October[54] 1988 until the office was renamed to the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet on 25 May 1989 to 15 March 1990[55] and President of the Soviet Union from 15 March 1990[59] to 25 December 1991.[60] The day following Gorbachev's resignation as President, the Soviet Union was formally dissolved.[57] |

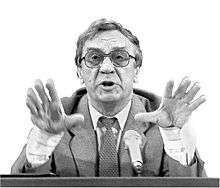

| Gennady Yanayev (1937–2010) (usurper) |

|

19 August 1991 ↓ 21 August 1991 |

— | Took power during the 2 days of the failed 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, with the State Committee on the State of Emergency. |

List of troikas

On three occasions—between Lenin's death and Stalin's rise; Stalin's death and Nikita Khrushchev's rise; and Khrushchev's fall and Leonid Brezhnev's consolidation of power—a form of collective leadership known as the troika ("triumvirate")[61] governed the Soviet Union, with no single individual holding leadership alone.[24][40]

| Members (Birth–Death) |

Tenure | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

↓ 1925[63] |

When Vladimir Lenin suffered his first stroke a Troika was established to govern the country in his place. The Troika consisted of Lev Kamenev, Joseph Stalin, and Grigory Zinoviev. The Troika was dissolved when Kamenev and Zinoviev decided to break with Stalin in 1925 and joined the faction led by Leon Trotsky.[63] Later, Kamenev, Zinoviev and Trotsky would be murdered at Stalin's orders. |

| Lev Kamenev (1883–1936)[64] |

Joseph Stalin (1878–1953)[13] |

Grigory Zinoviev (1883–1936)[65] | ||

|

|

|

↓ 26 June 1953[66] |

This Troika consisted of Georgy Malenkov, Lavrentiy Beria, and Vyacheslav Molotov[67] and ended when Malenkov and Molotov joined Nikita Khrushchev in the arrest and execution of Beria.[44] |

| Lavrentiy Beria (1899–1953)[40] |

Georgy Malenkov (1902–1988)[40] |

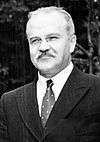

Vyacheslav Molotov (1890–1986)[40] | ||

.jpg) |

|

|

↓ 16 June 1977[24] |

The Troika consisted of the leading members of the collective leadership, and consisted of Brezhnev as First Secretary, Kosygin as Premier and Anastas Mikoyan as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. In 1965, Mikoyan was succeeded by Nikolai Podgorny. During Brezhnev's gradual consolidation of power, the Troika was "dissolved" when he succeeded Podgorny in 1977 as Presidium chairman.[24] However, the collective leadership continued to exist in a different shape after Podgorny's ouster in the Party leadership throughout the rest of Brezhnev's rule.[68] |

| Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982)[45] |

Alexei Kosygin (1904–1980)[45] |

Nikolai Podgorny (1903–1983)[45] | ||

See also

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- List of heads of state of the Soviet Union

- Premier of the Soviet Union

- List of presidents of the Russian Federation

Notes

- 1 2 Armstrong 1986, p. 169.

- 1 2 Armstrong 1986, p. 165.

- 1 2 Armstrong 1986, p. 98.

- ↑ Armstrong 1986, p. 93.

- ↑ Ginsburgs, Ajani & van den Berg 1989, p. 500.

- ↑ Armstrong 1989, p. 22.

- ↑ Brown 1996, p. 195.

- ↑ Brown 1996, p. 196.

- ↑ Brown 1996, p. 275.

- ↑ Gorbachev, M. (5 September 1991). ЗАКОН Об органах государственной власти и управления Союза ССР в переходный период [Law Regarding State Governing Bodies of the USSR in Transition] (in Russian). Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Lenin 1920, p. 516.

- ↑ Clark 1988, p. 373.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown 2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Gregory 2004, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 62.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 63.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 72.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 90.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 194.

- ↑ Brown 2009, pp. 231–33.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 246.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Service 2009, p. 378.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown 2009, p. 402.

- ↑ Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 13.

- 1 2 Brown 2009, p. 403.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 398.

- ↑ Zemtsov 1989, p. 146.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 481.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 487.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 489.

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 503.

- 1 2 3 Brown 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ Sakwa 1999, pp. 140–143.

- 1 2 Service 2009, p. 323.

- ↑ Service 1986, pp. 231–32.

- ↑ Green & Reeves 1993, p. 196.

- ↑ Service 2005, p. 154.

- 1 2 Service 2009, p. 331.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Service & 2009 332.

- ↑ Duiker & Spielvogel 2006, p. 572.

- ↑ Cook 2001, p. 163.

- ↑ Hill 1993, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Taubman 2003, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Service 2009, p. 377.

- ↑ Service 2009, p. 376.

- ↑ Schwartz 1971.

- ↑ Taubman 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Service 2009, p. 426.

- 1 2 Service 2009, p. 428.

- ↑ Service 2009, p. 433.

- ↑ Paxton 2004, p. 234.

- 1 2 Service 2009, p. 434.

- 1 2 Europa Publications Limited 2004, p. 302.

- 1 2 3 Paxton & 2004 235.

- ↑ Service 2009, p. 435.

- 1 2 3 Gorbachev 1996, p. 771.

- ↑ Service 2009, p. 503.

- ↑ Paxton 2004, p. 236.

- ↑ Paxton 2004, p. 237.

- ↑ Tinggaard & Svendsen 2009, p. 460.

- ↑ Reim 2002, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Rappaport 1999, pp. 141 & 326.

- ↑ Rappaport 1999, p. 140.

- ↑ Rappaport 1999, p. 325.

- ↑ Andrew & Gordievsky 1990, pp. 423–24.

- ↑ Marlowe 2005, p. 140.

- ↑ Baylis 1989, p. 98.

Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher; Gordievsky, Oleg (1990). KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0060166052.

- Brown, Archie (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827344-8.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0061138799.

- Armstrong, John Alexander (1986). Ideology, Politics, and Government in the Soviet Union: An Introduction. University Press of America. ASIN B002DGQ6K2.

- Bacon, Edwin; Sandle, Mark (2002). Brezhnev Reconsidered. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333794630.

- Baylis, Thomas A. (1989). Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-944-4.

- Cook, Bernard (2001). Europe since 1945: An Encyclopedia. 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0815313366.

- Clark, William (1988). Lenin: The Man Behind the Mask. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571154609.

- Duiker, William; Spielvogel, Jackson (2006). The Essential World History. Cengage Learning. p. 572. ISBN 978-0495902270.

- Europa Publications Limited (2004). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857431872.

- Ginsburgs, George; Ajani, Gianmaria; van den Berg, Gerard Peter (1989). Soviet Administrative Law: Theory and Policy. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-0792302889.

- Gorbachev, Mikhail (1996). Memoirs. University of Michigan: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385480192.

- Green, William C.; Reeves, W. Robert (1993). The Soviet Military Encyclopedia: P–Z. University of Michigan: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813314310.

- Gregory, Paul (2004). The Political Economy of Stalinism: Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521533676.

- Hill, Kenneth (1993). Cold War chronology: Soviet–American relations, 1945–1991. University of Michigan: Congressional Quarterly. ISBN 978-0871879219.

- Lenin, Vladimir (1920). Collected Works. 31. p. 516.

- Marlowe, Lynn Elizabeth (2005). GED Social Studies. Research and Education Association. ISBN 978-0738601274.

- Paxton, John (2004). Leaders of Russia and the Soviet Union: from the Romanov dynasty to Vladimir Putin. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1579581329.

- Phillips, Steven. Lenin and the Russian Revolution. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32719-4.

- Rappaport, Helen (1999). Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576070840.

- Sakwa, Richard (1999). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917–1991. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12290-0.

- Reim, Melanie (2002). The Stalinist Empire. Twenty-first Century Books. ISBN 978-0-7613-2558-1.

- Service, Robert (2009). History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0674034938.

- Service, Robert (2005). Stalin: A Biography. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674016972.

- Taubman, William (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393051445.

- Tinggaard Svendsen, Gert; Svendsen, Gunnar Lind Haase (2009). Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1845423230.

- Zemtsov, Ilya (1989). Chernenko: The Last Bolshevik: The Soviet Union on the Eve of Perestroika. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0887382604.

External links

- Succession of Power in the USSR from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Heads of State and Government of the Soviet Union (1922–1991)