Mad Max

| Mad Max | |

|---|---|

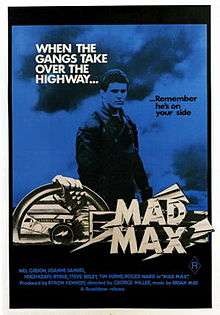

Australian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Miller |

| Produced by | Byron Kennedy |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Brian May |

| Cinematography | David Eggby |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Roadshow Entertainment |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes[1] |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$350,000–400,000 |

| Box office | US$100 million |

Mad Max is a 1979 Australian post-apocalyptic dystopian exploitation action film directed by George Miller, produced by Byron Kennedy, and starring Mel Gibson as "Mad" Max Rockatansky, Joanne Samuel, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Steve Bisley, Tim Burns, and Roger Ward. James McCausland and Miller wrote the screenplay from a story by Miller and Kennedy. The film presents a tale of societal collapse, murder, and vengeance set in a future Australia, in which a vengeful policeman becomes embroiled in a feud with a vicious motorcycle gang. Principal photography took place in and around Melbourne, Australia, and lasted six weeks.

The film initially received a polarized reception upon its release in April 1979, although it won three AACTA Awards and attracted a cult following, while its critical reputation has grown since. The film earned more than $100 million worldwide in gross revenue. It held the Guinness record for most profitable film from 1980-1999[2] and has been credited for further opening up the global market to Australian New Wave films. The film became the first in a series, giving rise to the sequels Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981), Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Fury Road (2015).

Plot

In the not-too-distant future in which society is teetering upon the brink of collapse, berserk motorbike gang member Crawford "Nightrider" Montazano (Vincent Gil) steals a Pursuit Special, which he uses to escape from police custody after killing a rookie officer of an Australian highway patrol called the Main Force Patrol (MFP). Even though he manages to elude other MFP officers, the MFP's top-pursuit man Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson) then engages the less-skilled Nightrider in a high-speed chase. He breaks off first, but then is unable to recover his concentration before he and his girlfriend are killed in a fiery crash.

Nightrider's motorbike gang, led by Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne) and Bubba Zanetti (Geoff Parry), run roughshod over a town, vandalizing property, stealing fuel, and terrorizing the population. Max and fellow officer Jim Goose (Steve Bisley) arrest Toecutter's young protégé Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns), who was too high to leave the scene of the gang's rape of a young couple. When neither the rape victims nor any of the townspeople show for Johnny's trial, the federal courts close the case, thus releasing Johnny into Bubba's custody over Goose's furious objections.

While Goose visits a nightclub in the city the next day, Johnny sabotages his police motorbike. After being thrown into a field at high speed uninjured during a ride, Goose borrows a ute to haul his damaged bike back to the MFP. However, Johnny ambushes Goose off the road with a drum brake and reluctantly burns him alive by throwing a match at the inverted ute. After seeing Goose's charred body in a hospital intensive-care unit, Max becomes disillusioned with the MFP and informs his superior Fifi Macaffee (Roger Ward) that he will resign. Fifi convinces Max to take a vacation first before he can make his final decision about leaving.

While on vacation, Max's wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) and their infant son Sprog (Brendan Heath) encounter Toecutter and his gang, who attempt to molest Jessie while buying ice cream. Max and his family then flee to a remote farm owned by an elderly friend named May Swaisey (Sheila Florance), but the gang manages to follow them. Jessie and Sprog escape from the gang, only to be run over by them.

With Sprog having been killed instantly and Jessie near death in a hospital ICU, an enraged Max dons his police leathers and takes the supercharged black Pursuit Special from the MFP garage to pursue the gang. He eliminates several gang members off a bridge at high speed, kills Bubba during an ambush, and forces Toecutter into the path of a speeding semi-trailer truck. Max eventually locates Johnny, who is looting a deceased car-crash victim for a pair of boots. Max handcuffs Johnny's ankle to a wrecked vehicle, and sets a crude time-delay fuse involving a slow petrol-leak and Johnny's lighter. Max throws Johnny a hacksaw, leaving him the choice of sawing through either the handcuffs or his ankle in order to escape within the given time-limit. As Max drives away from the bridge, the vehicle explodes, apparently killing Johnny. Now a shell of his former self, Max drives on to points unknown, pushing deep into the Outback.

Cast

- Mel Gibson as "Mad" Max Rockatansky

- Joanne Samuel as Jessie Rockatansky

- Hugh Keays-Byrne as Toecutter

- Steve Bisley as Jim "Goose" Rains

- Tim Burns as Johnny the Boy

- Roger Ward as Fred "Fifi" Macaffee

- Geoff Parry as Bubba Zanetti

- Lisa Aldenhoven as Hospital Nurse

- Peter Felmingham as Emergency Room Doctor

- Neil Thompson as TV News Anchor

- David Bracks as Mudguts

- Bertrand Cadart as Clunk

- David Cameron as Barry

- Stephen Clark as Sarse

- Jonathan Hardy as Police Commissioner Labatouche

- Robina Chaffey as Nightclub Singer

- Brendan Heath as Sprog Rockatansky

- Jerry Day as Ziggy

- Howard Eynon as Diabando

- Max Fairchild as Benno

- John Farndale as Grinner

- Sheila Florence as May Swaisey

- Nic Gazzana as Starbuck

- Paul Johnstone as Cundalini

- Vincent Gil as Crawford "The Nightrider" Montazano

- Lulu Pinkus as The Nightrider's Girlfriend

- Steve Millichamp as "Roop"

- John Ley as "Charlie"

- George Novak as "Scuttle"

- Reg Evans as Station Master

- Nico Lathouris as Mechanic

Production

Development

George Miller was a medical doctor in Sydney, working in a hospital emergency room where he saw many injuries and deaths of the types depicted in the film. He also witnessed many car accidents growing up in rural Queensland and had as a teenager lost at least three friends in accidents.[3]

While in residency at a Sydney hospital, Miller met amateur filmmaker Byron Kennedy at a summer film school in 1971. The duo produced a short film, Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, which was screened at a number of film festivals and won several awards. Eight years later, the duo produced Mad Max, working with first-time screenwriter James McCausland (who appears in the film as the bearded man in an apron in front of the diner).

According to Miller, his interest while writing Mad Max was "a silent movie with sound", employing highly kinetic images reminiscent of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd while the narrative itself was basic and simple. Miller believed that audiences would find his violent story more believable if set in a bleak dystopian future.[4] Screenwriter McCausland drew heavily from his observations of the 1973 oil crisis' effects on Australian motorists:

Yet there were further signs of the desperate measures individuals would take to ensure mobility. A couple of oil strikes that hit many pumps revealed the ferocity with which Australians would defend their right to fill a tank. Long queues formed at the stations with petrol—and anyone who tried to sneak ahead in the queue met raw violence. ... George and I wrote the [Mad Max] script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late.

Kennedy and Miller first took the film to Graham Burke of Roadshow, who was enthusiastic. The producers felt they would be unable to raise money from the government bodies "because Australian producers were making art films, and the corporations and commissions seemed to endorse them whole-heartedly", according to Kennedy.[6]

They designed a 40-page presentation, circulated it widely, and eventually raised the money. Kennedy and Miller also contributed funds themselves by doing three months of emergency medical calls, with Kennedy driving the car while Miller did the doctoring.[6] Miller claimed the final budget was between $350,000 and $400,000.[7] His brother Bill Miller was an associate producer on the film.[8]

Casting

George Miller had considered an American actor to "get the film seen as widely as possible" and even travelled to Los Angeles, but eventually opted to not do so as "the whole budget would be taken up by a so-called American name."[4] So instead the cast would deliberately feature lesser known actors so they did not carry past associations with them.[3] Miller's first choice for the role of Max was the Irish-born James Healey, who at the time worked at a Melbourne abattoir and was seeking a new acting job. Upon reading the script Healey declined, finding the meager, terse dialogue too unappealing.[9]

Casting director Mitch Matthews invited for Mad Max a class of recent National Institute of Dramatic Art graduates, specifically asking a NIDA teacher for "spunky young guys". Among these actors was Mel Gibson, whose audition impressed Miller and Matthews and earned him the role of Max. An apocryphal tale stated that Gibson went to auditions in poor shape following a fight, but this has been denied by both Matthews and Miller. Gibson's friend and classmate Steve Bisley, who worked with him in his only screen role, 1976's Summer City, became Max's partner Jim Goose. A classmate of both, Judy Davis, was said to have auditioned and passed over,[9] but Miller has declared she was only in Matthews' studio to accompany Gibson and Bisley.[4]

Most of the biker gang extras were members of actual Australian outlaw motorcycle clubs and rode their own motorcycles in the film. They were even forced to ride the motorcycles from their residence in Sydney to the shooting locations in Melbourne because the budget did not allow for aerial transport.[4] Three of the main cast members (Hugh Keays-Byrne, Roger Ward and Vincent Gil) had previously appeared in Stone, a 1974 film about biker gangs that is said to have inspired Miller.[10]

Vehicles

Max's yellow Interceptor was a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan (previously, a Victorian police car) with a 351 c.i.d. Cleveland V8 engine.[11]

The Big Bopper, driven by Roop and Charlie, was also a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan and a former Victorian Police car, but was powered by a 302 c.i.d. V8.[12] The March Hare, driven by Sarse and Scuttle, was an in-line-six-powered 1972 Ford Falcon XA sedan (this car was formerly a Melbourne taxi cab).[13]

The most memorable car, Max's black Pursuit Special was a 1973 Ford XB Falcon GT351, a limited edition hardtop (sold in Australia from December 1973 to August 1976), which was primarily modified by Murray Smith, Peter Arcadipane, and Ray Beckerley. The main modifications are the Concorde front end and the supercharger protruding through the bonnet (for looks only; it was not functional). The Concorde front was a fairly new accessory at the time, designed by Peter Arcadipane at Ford Australia as a showpiece, and later became available to the general public because of its popularity.[14] After filming of the first movie was completed, the car went up for sale, but no buyers were found; eventually it was given to Smith.

When production of The Road Warrior (1981) began, Miller brought the car back for use in the sequel. Once filming was over the car was left at a wrecking yard in Adelaide since it again found no buyers, and was bought and restored by Bob Forsenko. Eventually it was sold again and was put on display in the Cars of the Stars Motor Museum in Cumbria, England. When the museum closed, the black on black car went to a collection in the Dezer Museum in Miami, Florida.[15]

The Nightrider's vehicle, another Pursuit Special (one of two in the film), was a 1972 Holden Monaro Coupe HQ LS, also tuned but deliberately damaged to look like it has been involved in crashes.[16]

The car driven by the young couple, that is vandalised and then finally destroyed by the bikers, is a 1959 Chevrolet Bel Air Sedan, also pretuned to look like a hot-rod car with fake fuel injection stacks, fat tires, and a flame red paint job.

Of the motorcycles that appear in the film, 14 were Kawasaki Kz1000 donated by a local Kawasaki dealer. All were modified in appearance by Melbourne business La Parisienne—one as the MFP bike ridden by 'The Goose' and the balance for members of the Toecutter's gang, played in the film by members of a local Victorian motorcycle club, the Vigilanties.[17]

By the end of filming, fourteen vehicles had been destroyed in the chase and crash scenes, including the director's personal Mazda Bongo (the small, blue van that spins uncontrollably after being struck by the Big Bopper in the film's opening chase).[18]

Filming

Originally, filming was scheduled to take ten weeks—six weeks of first unit, and four weeks on stunt and chase sequences. However, four days into shooting, Rosie Bailey, who was originally cast as Max's wife, was injured in a bike accident. Production was halted, and Bailey was replaced by Joanne Samuel, causing a two-week delay.

In the end, the shoot took six weeks over November and December 1977, with a further six-week second unit. The unit reconvened two months later, in May 1978, and spent another two weeks doing second unit shots and re-staging some stunts.[6] Miller described the whole experience as "guerrilla filmmaking", where the crew would close roads without filming permits, not use walkie-talkies because their frequency coincided with the police radio, and after filming was done Miller and Kennedy would even sweep down the roads. Still, as filming progressed the Victoria Police became interested in the production, helping the crew by closing down roads and escorting the vehicles.[4] Because of the film's low budget, almost all the police uniforms in the film were made of vinyl leather, with only one genuine leather uniform made for stunt sequences involving Bisley and Gibson.

Shooting took place in and around Melbourne. Many of the car chase scenes for Mad Max were filmed near the town of Little River, northeast of Geelong. The early town scenes with the Toe Cutter Gang were filmed in the main street of Clunes, north of Ballarat. Much of the streetscape remains unchanged. Some scenes were filmed at Tin City at Stockton Beach.[19][20] The "execution of the mannequin" scene was filmed at Seaford Beach in Seaford, Victoria.

Mad Max was one of the first Australian films to be shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens,[7] although Peter Weir's The Cars That Ate Paris (1974) was shot in anamorphic four years earlier.[21] Miller's desire to shoot in anamorphic made him seek a set of Todd-AO wide angle lenses used by Sam Peckinpah to film The Getaway (1972), which were damaged enough in that shoot to get discarded in Australia. The only one which worked properly was a 35mm lens which was employed in the whole of Mad Max.[4]

Post-production

The film's post-production was done at a friend's apartment in North Melbourne, with Wilson and Kennedy editing the film in the small lounge room on a home-built editing machine that Kennedy's father, an engineer, had designed for them. Wilson and Kennedy also performed sound editing there.

Tony Patterson edited the film for four months, then had to leave because he was contracted to make Dimboola (1979). George Miller took over editing with Cliff Hayes, and they worked on it for three months. Kennedy and Miller did the final cut,[6] in a process Miller described as "he would cut sound in the lounge room and I’d cut picture in the kitchen." Professional sound engineer Roger Savage would perform the sound mixing in the studio he worked after finishing his work with Little River Band, and employed timecoding techniques that were unseen in Australian cinema.[4]

Music

The musical score for Mad Max was composed and conducted by Australian composer Brian May (not to be confused with the guitarist of the English rock band Queen). Miller wanted a Gothic, Bernard Herrmann–type score and hired May after hearing his work for Patrick (1978).[3] "With the little budget that we had we went ahead and did it, and spent a lot of time on it," said May. "George was marvelous to work with; he had a lot of ideas about what he wanted although he wasn’t a musician."[22] A soundtrack album was released in 1980 by Varèse Sarabande.[23]

Release

Mad Max was first released in Australia through Roadshow Entertainment (now Village Roadshow Pictures) in 1979.[24]

The movie was sold overseas for $1.8 million, with American International Pictures releasing in the United States and Warner Bros. handling the rest of the world.[7]

When shown in the United States during 1980, the original Australian dialogue was redubbed by an American crew.[25] American International Pictures distributed this dub after it underwent a management re-organisation.[26] Much of the Australian slang and terminology was also replaced with American usages (examples: "Oi!" became "Hey!", "See looks!" became "See what I see?", "windscreen" became "windshield", "very toey" became "super hot", and "proby"—probationary officer—became "rookie"). AIP also altered the operator's duty call on Jim Goose's bike in the beginning of the film (it ended with "Come on, Goose, where are you?"). The only dubbing exceptions were the voice of the singer in the Sugartown Cabaret (played by Robina Chaffey), the voice of Charlie (played by John Ley) through the mechanical voice box, and Officer Jim Goose (Steve Bisley), singing as he drives a truck before being ambushed. Since Mel Gibson was not well known to American audiences at the time, trailers and television spots in the United States emphasised the film's action content.

The original Australian dialogue track was finally released in North America in 2000 in a limited theatrical reissue by MGM, the film's current rights holders. It has since been released in the US on DVD with the US and Australian soundtracks on separate tracks.[27][28]

The film was banned in New Zealand and Sweden, in the former because of the scene where Goose is burned alive inside his vehicle: it unintentionally mirrored an incident with a real gang shortly before the film's release. It was later shown in New Zealand in 1983 after the success of the sequel, with an 18 certificate.[29] The ban in Sweden was removed in 2005, and it has since been shown on television and sold on home media there.

Reception

Upon its release, the film polarized critics. In a 1979 review, the Australian social commentator and film producer Phillip Adams condemned Mad Max, saying that it had "all the emotional uplift of Mein Kampf" and would be "a special favourite of rapists, sadists, child murderers and incipient [Charles] Mansons".[30] After its United States release, Tom Buckley of The New York Times called the film "ugly and incoherent".[31] However, Variety magazine praised the directorial debut by Miller.[32]

Mad Max grossed A$5,355,490 at the box office in Australia and over US$100 million worldwide.[33][34] It was the most profitable film ever made at the time, holding the Guinness World Record for the highest box office to budget ratio of any motion picture, ceding the record to The Blair Witch Project in 1999.[35][36] The film was awarded three Australian Film Institute Awards in 1979 (for editing, sound, and musical score). It was also nominated for Best Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actor (Hugh Keays-Byrne) by the Australian Film Institute. The film also won the Special Jury Award at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival.[37]

Mad Max holds an 89% "Fresh" rating on review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes, based on 54 positive critic reviews, with consensus being "Staging the improbable car stunts and crashes to perfection, director George Miller succeeds completely in bringing the violent, post-apocalyptic world of Mad Max to visceral life."[38] The film has been included in "best films of all time" lists by The New York Times[39] and the The Guardian.[40]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Winner/Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACTA Award (1979 AFI Awards) |

Best Film | Byron Kennedy | Nominated |

| Best Direction | George Miller | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Nominated | ||

| James McCausland | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Hugh Keays-Byrne | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Cliff Hayes | Won | |

| Tony Paterson | Won | ||

| Best Original Music Score | Brian May | Won | |

| Best Sound | Ned Dawson | Won | |

| Byron Kennedy | Won | ||

| Roger Savage | Won | ||

| Gary Wilkins | Won | ||

| Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival | Special Jury Award | George Miller | Won |

Legacy

References

- ↑ "MAD MAX (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ "Movie Budgets". the-numbers.com. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- 1 2 3 Scott Murray & Peter Beilby, "George Miller: Director", Cinema Papers, May–June 1979 p369-371

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Filmmaker Interview: George Miller

- ↑ James McCausland (4 December 2006). "Scientists' warnings unheeded". The Courier-Mail. News.com.au. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Beilby & Scott Murray, "Byron Kennedy", Cinema Papers, May–June 1979 p366

- 1 2 3 David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p241-243

- ↑ "Mad Max Tail Credits" (PDF). Ozmovies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- 1 2 Clarkson, Wensley (2005). "6". Mel Gibson - Man on a Mission. John Blake Publishing. ISBN 1784184756.

- ↑ Stone rewatched: the Australian bikie movie that inspired Mad Max

- ↑ "Mad Max Cars – Max's Yellow Interceptor (4 Door XB Sedan)". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars – Big Boppa/Big Bopper". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars – March Hare". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Movies – The History of the ''Interceptor'', Part 1". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "Cars of the Stars Motor Museum". Carsofthestars.com. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars – The Nightrider's Monaro". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars – Toecutter's Gang (Bikers)". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Lyttelton, Oliver (12 April 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About 'Mad Max'". Indiewire. Snagfilms. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Elliot, Tim (9 January 2014). "Welcome to Tin City, Stockton". The Newcastle Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Tin City, Stockton Beach". Parliament of New South Wales. 27 August 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Harland Smith, Richard. "The Cars That Ate Paris". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Flanagan, Graeme (14 May 2015). "A Conversation with Brian May". CinemaScore (published 1983) (11/12). Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Osborne, Jerry (2010). Movie/TV Soundtracks and Original Cast Recordings Price and Reference Guide. Port Townsend, Washington: Osborne Enterprises Publishing. p. 353. ISBN 0932117376.

- ↑ Moran, Albert; Vieth, Errol (2005). "Kennedy Miller Productions". Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema. Scarecrow Press (Rowman & Littlefield). p. 174. ISBN 0-8108-5459-7. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ↑ Herx, Henry (1988). "Mad Max". The Family Guide to Movies on Video. The Crossroad Publishing Company. p. 163 (pre-release version). ISBN 0-8245-0816-5.

- ↑ McFarlane, Brian (1988). Australian Cinema. Columbia University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-231-06728-3. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ↑ Zad, Martie (29 December 2001). "Gibson's Voice Returns on New 'Mad Max' DVD". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Publishing. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Mad Max (1979)". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ↑ Carroll, Larry (3 February 2009). "Greatest Movie Badasses Of All Time: Mad Max – Movie News Story | MTV Movie News". Mtv.com. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ↑ Phillip Adams, The Bulletin, 1 May 1979; cited by urban cinefile, 2010, "Mad Max". Adams has since remained a prominent opponent of screen violence. He has also been consistent in his criticism of Mel Gibson's political and social opinions.

- ↑ Buckley, Tom (14 June 1980). "Mad Max". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Mad Max Review – Read Variety's Analysis Of The Movie Mad Max". Variety.com. 1979-01-01. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Film Victoria - Australian Films at the Australian Box Office" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Haenni, Sabine; Barrow, Sarah; White, John, eds. (2014). "Mad Max (1979)". The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films. Routledge. pp. 323–326. ISBN 9781317682615.

- ↑ Robertson, Patrick (1991). Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats. Abbeville Press. p. 34. ISBN 9781558592360.

- ↑ "Mad Max : SE". DVD Times. 19 January 2002. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Awards for Mad Max at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Mad Max (1979)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. 29 April 2003. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ↑ "1000 films to see before you die". The Guardian. 4 July 2007.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mad Max |

- Official website—home to the original Mad Max film, maintained by members of the cast and crew.

- Mad Max at the Internet Movie Database

- Mad Max at the TCM Movie Database

- Mad Max at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mad Max at Oz Movies