Microburst

A microburst is a small downdraft that moves in a way opposite to a tornado. Microbursts are found in strong thunderstorms.[1] There are two types of microbursts within a thunderstorm: wet microbursts and dry microbursts. They go through three stages in their cycle, the downburst, outburst, and cushion stages. A microburst can be particularly dangerous to aircraft, especially during landing, due to the wind shear caused by its gust front. Several fatal crashes have been attributed to the phenomenon over the past several decades, and flight crew training goes to great lengths on how to properly recover from a microburst/wind shear event.

A microburst often has high winds that can knock over fully grown trees. They usually last from a couple of seconds to several minutes.

History of term

The term was defined by mesoscale meteorology expert Ted Fujita as affecting an area 4 km (2.5 mi) in diameter or less, distinguishing them as a type of downburst and apart from common wind shear which can encompass greater areas.[2] Fujita also coined the term macroburst for downbursts larger than 4 km (2.5 mi).[3]

A distinction can be made between a wet microburst which consists of precipitation and a dry microburst which typically consists of virga.[4] They generally are formed by precipitation-cooled air rushing to the surface, but they perhaps also could be powered from the high speed winds of the jet stream deflected toward the surface by a thunderstorm or by dynamical processes (see rear flank downdraft).

Microbursts are recognized as capable of generating wind speeds higher than 75 m/s (170 mph; 270 km/h).

Microbursts have also been called air bombs.[5]

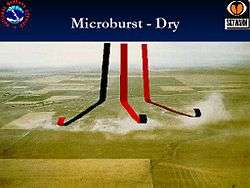

Dry microbursts

When rain falls below the cloud base or is mixed with dry air, it begins to evaporate and this evaporation process cools the air. The cool air descends and accelerates as it approaches the ground. When the cool air approaches the ground, it spreads out in all directions and this divergence of the wind is the signature of the microburst. High winds spread out in this type of pattern showing little or no curvature are known as straight-line winds.[6]

Dry microbursts, produced by high based thunderstorms that generate little to no surface rainfall, occur in environments characterized by a thermodynamic profile exhibiting an inverted-V at thermal and moisture profile, as viewed on a Skew-T log-P thermodynamic diagram. Wakimoto (1985) developed a conceptual model (over the High Plains of the United States) of a dry microburst environment that comprised three important variables: mid-level moisture, a deep and dry adiabatic lapse rate in the sub-cloud layer, and low surface relative humidity.

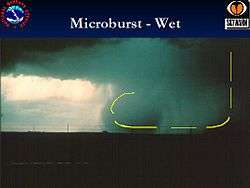

Wet microbursts

Wet microbursts are downbursts accompanied by significant precipitation at the surface which are warmer than their environment (Wakimoto, 1998).[7] These downbursts rely more on the drag of precipitation for downward acceleration of parcels than negative buoyancy which tend to drive "dry" microbursts. As a result, higher mixing ratios are necessary for these downbursts to form (hence the name "wet" microbursts). Melting of ice, particularly hail, appears to play an important role in downburst formation (Wakimoto and Bringi, 1988), especially in the lowest 1 km (0.62 mi) above ground level (Proctor, 1989). These factors, among others, make forecasting wet microbursts a difficult task.

| Characteristic | Dry Microburst | Wet Microburst |

|---|---|---|

| Location of highest probability within the United States | Midwest / West | Southeast |

| Precipitation | Little or none | Moderate or heavy |

| Cloud bases | As high as 500 mb (hPa) | As high as 850 mb (hPa) |

| Features below cloud base | Virga | Precipitation shaft |

| Primary catalyst | Evaporative cooling | Downward transport of higher momentum |

| Environment below cloud base | Deep dry layer/low relative humidity/dry adiabatic lapse rate | Shallow dry layer/high relative humidity/moist adiabatic lapse rate |

| Surface outflow pattern | Omni-directional | Gusts of the direction of the mid-level wind |

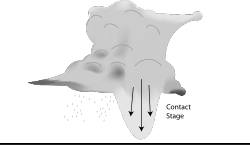

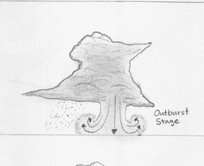

Development stages of microbursts

The evolution of downbursts is broken down into three stages: the contact stage, the outburst stage, and the cushion stage.

-

A downburst initially develops as the downdraft begins its descent from the cloud base. The downdraft accelerates, and within minutes reaches the ground (contact stage). It is during the contact stage that the highest winds are observed.

-

During the outburst stage, the wind "curls" as the cold air of the downburst moves away from the point of impact with the ground.

-

During the cushion stage, winds about the curl continue to accelerate, while the winds at the surface slow due to friction.[1]

- ^ University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign. Microbursts. Retrieved on 2008-08-04.

Physical processes of dry and wet microbursts

.svg.png)

Basic physical processes using simplified buoyancy equations

Start by using the vertical momentum equation:

By decomposing the variables into a basic state and a perturbation, defining the basic states, and using the ideal gas law (), then the equation can be written in the form

where B is buoyancy. The virtual temperature correction usually is rather small and to a good approximation; it can be ignored when computing buoyancy. Finally, the effects of precipitation loading on the vertical motion are parametrized by including a term that decreases buoyancy as the liquid water mixing ratio () increases, leading to the final form of the parcel's momentum equation:

The first term is the effect of perturbation pressure gradients on vertical motion. In some storms this term has a large effect on updrafts (Rotunno and Klemp, 1982) but there is not much reason to believe it has much of an impact on downdrafts (at least to a first approximation) and therefore will be ignored.

The second term is the effect of buoyancy on vertical motion. Clearly, in the case of microbursts, one expects to find that B is negative meaning the parcel is cooler than its environment. This cooling typically takes place as a result of phase changes (evaporation, melting, and sublimation). Precipitation particles that are small, but are in great quantity, promote a maximum contribution to cooling and, hence, to creation of negative buoyancy. The major contribution to this process is from evaporation.

The last term is the effect of water loading. Whereas evaporation is promoted by large numbers of small droplets, it only requires a few large drops to contribute substantially to the downward acceleration of air parcels. This term is associated with storms having high precipitation rates. Comparing the effects of water loading to those associated with buoyancy, if a parcel has a liquid water mixing ratio of 1.0 g kg−1, this is roughly equivalent to about 0.3 K of negative buoyancy; the latter is a large (but not extreme) value. Therefore, in general terms, negative buoyancy is typically the major contributor to downdrafts.[8]

Negative vertical motion associated only with buoyancy

Using pure "parcel theory" results in a prediction of the maximum downdraft of

where NAPE is the negative available potential energy,

and where LFS denotes the level of free sink for a descending parcel and SFC denotes the surface. This means that the maximum downward motion is associated with the integrated negative buoyancy. Even a relatively modest negative buoyancy can result in a substantial downdraft if it is maintained over a relatively large depth. A downward speed of 25 m/s (56 mph; 90 km/h) results from the relatively modest NAPE value of 312.5 m2 s−2. To a first approximation, the maximum gust is roughly equal to the maximum downdraft speed.[8]

Danger to aircraft

The scale and suddenness of a microburst makes it a notorious danger to aircraft, particularly those at low altitude which are taking off or landing. The following are some fatal crashes and/or aircraft incidents that have been attributed to microbursts in the vicinity of airports:

- A BOAC Canadair C-4 Argonaut (G-ALHE), Kano Airport - 24 June 1956.

- A Malév Ilyushin Il-18 (HA-MOC), Copenhagen Airport – 28 August 1971.

- Eastern Air Lines Flight 66 Boeing 727-225(N8845E), John F. Kennedy International Airport – 24 June 1975[9]

- Pan Am Flight 759 Boeing 727-235 (N4737), New Orleans International Airport – 9 July 1982[9]

- Delta Air Lines Flight 191 Lockheed L-1011 TriStar (N726DA), Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport – 2 August 1985[9]

- Martinair Flight 495 McDonnell Douglas DC-10 (PH-MBN), Faro Airport – 21 December 1992[10]

- USAir Flight 1016 Douglas DC-9 (N954VJ), Charlotte/Douglas International Airport – 2 July 1994

- Goodyear Blimp GZ-20A (N1A, "Stars and Stripes"), Coral Springs, Florida – 16 June 2005

- Bhoja Air Flight 213 Boeing 737-200 (AP-BKC), Islamabad International Airport, Islamabad, Pakistan – April 20, 2012

A microburst often causes aircraft to crash when they are attempting to land (the above-mentioned BOAC and Pan Am flights are notable exceptions). The microburst is an extremely powerful gust of air that, once hitting the ground, spreads in all directions. As the aircraft is coming in to land, the pilots try to slow the plane to an appropriate speed. When the microburst hits, the pilots will see a large spike in their airspeed, caused by the force of the headwind created by the microburst. A pilot inexperienced with microbursts would try to decrease the speed. The plane would then travel through the microburst, and fly into the tailwind, causing a sudden decrease in the amount of air flowing across the wings. The decrease in airflow over the wings of the aircraft causes a drop in the amount of lift produced. This decrease in lift combined with a strong downward flow of air can cause the thrust required to remain at altitude to exceed what is available, thus causing the aircraft to stall.[9] If the plane is at a low altitude shortly after takeoff or during landing, it will not have sufficient altitude to recover.

The strongest microburst recorded thus far occurred at Andrews Field, Maryland on August 1st 1983, with wind speeds reaching 240.5 km/h (149.5 mi/h).[11]

Danger to buildings

- On August 9, 2016, a wet microburst struck the city of Cleveland Heights, Ohio, an eastern suburb of Cleveland.[12][13] The storm developed very quickly. Thunderstorms developed west of Cleveland at 9 PM, and the National Weather Service issued a severe thunderstorm warning at 9:55 PM. The storm had passed over Cuyahoga County by 10:20 PM.[14] Lightning struck 10 times per minute over Cleveland Heights.[14] and 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) winds knocked down hundreds of trees and utility poles.[13][15] More than 45,000 people lost power, with damage so severe that nearly 6,000 homes remained without power two days later.[15]

- On July 22, 2016 a wet microburst hit portions of Kent and Providence Counties in Rhode Island, causing wind damage in the cities of Cranston, Rhode Island and West Warwick, Rhode Island. Numerous fallen trees were reported, as well as downed powerlines and minimal property damage. Thousands of people were without power for several hours. The storm occurred late at night, and no injuries were reported.

- On June 23, 2015 a macroburst hit portions of Gloucester and Camden Counties in New Jersey causing widespread damage mostly due to falling trees. Electrical utilities were affected for several days causing protracted traffic signal disruption and closed businesses.

- On August 23, 2014, a dry microburst hit Mesa, Arizona. It ripped the roof off of half a building and a shed, nearly damaging the surrounding buildings. No serious injuries were reported.

- On December 21, 2013 a wet microburst hit Brunswick, Ohio. The roof was ripped off of a local business; the debris damaged several houses and cars near the business. Due to the time, between 1 am and 2 am, there were no injuries.

- On July 9, 2012, a wet microburst hit an area of Spotsylvania County, Virginia near the border of the city of Fredericksburg, causing severe damage to two buildings. One of the buildings was a children's cheerleading center. Two serious injuries were reported.

- On July 1, 2012, a wet microburst hit DuPage County, Illinois, a county 15 to 30 mi (24 to 48 km) west of Chicago. The microburst left 250,000 Commonwealth Edison users without power. Many homes did not recover power for one week. Several roads were closed due to 200 reported fallen trees.[16]

- On June 22, 2012, a wet microburst hit the town of Bladensburg, Maryland, causing severe damage to trees, apartment buildings, and local roads. The storm caused an outage in which 40,000 customers lost power.

- On September 8, 2011, at 5:01 PM, a dry microburst hit Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada causing several aircraft shelters to collapse. Multiple aircraft were damaged and eight people were injured.[17]

- On September 22, 2010 in the Hegewisch neighborhood of Chicago, a wet microburst hit, causing severe localized damage and localized power outages, including fallen-tree impacts into at least four homes. No fatalities were reported.[18]

- On September 16, 2010, just after 5:30 PM, a wet macroburst with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h) hit parts of Central Queens in New York City, causing extensive damage to trees, buildings, and vehicles in an area 8 miles long and 5 miles wide. Approximately 3,000 trees were knocked down by some reports. There was one fatality when a tree fell onto a car on the Grand Central Parkway.[19][20]

- On June 24, 2010, shortly after 4:30 PM, a wet microburst hit the city of Charlottesville, Virginia. Field reports and damage assessments show that Charlottesville experienced numerous downbursts during the storm, with wind estimates at over 75 mph (121 km/h). In a matter of minutes, trees and downed power lines littered the roadways. A number of houses were hit by trees. Immediately after the storm, up to 60,000 Dominion Power customers in Charlottesville and surrounding Albemarle County were without power.[21]

- On June 11, 2010, around 3:00 AM, a wet microburst hit a neighborhood in southwestern Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It caused major damage to four homes, all of which were occupied. No injuries were reported. Roofs were blown off of garages and walls were flattened by the estimated 100 mph (160 km/h) winds. The cost of repairs was thought to be $500,000 or more.[22]

- On May 2, 2009, the lightweight steel and mesh building in Irving, Texas used for practice by the Dallas Cowboys football team was flattened by a microburst, according to the National Weather Service.[23]

- On March 12, 2006, a microburst hit Lawrence, Kansas. 60 percent of the University of Kansas campus buildings sustained some form of damage from the storm. Preliminary estimates put the cost of repairs at between $6 million and $7 million.[24]

See also

- Convective storm detection

- Downburst

- List of microbursts

- Low level windshear alert system (LLWAS)

- Planetary boundary layer (PBL)

- Squall

- Tornado

- Vertical draft

- Windthrow

References

Notes

- ↑ http://news.discovery.com/earth/weather-extreme-events/what-is-a-microburst-140515.htm

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology. Microburst. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology. Macroburst. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Fernando Caracena, Ronald L. Holle, and Charles A. Doswell III. Microbursts: A Handbook for Visual Identification. Retrieved on 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Stump, Scott (October 21, 2016). "The mystery of the Bermuda Triangle may have finally been solved". Today. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology. Straight-line wind. Retrieved on 2008-08-01.

- ↑

- Fujita, T.T. (1985). "The Downburst, microburst and macroburst". SMRP Research Paper 210, 122 pp.

- 1 2 Charles A. Doswell III. Extreme Convective Windstorms: Current Understanding and Research. Retrieved on 2008-08-04.

- 1 2 3 4 NASA Langley Air Force Base. Making the Skies Safer From Windshear. Retrieved on 2006-10-22.

- ↑ Aviation Safety Network. Damage Report. Retrieved on 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness Book of World Records 2014. The Jim Pattinson Group. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ↑ Roberts, Samantha (August 10, 2016). "What happened in Cleveland Heights Tuesday night?". KLTV. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Steer, Jen; Wright, Matt (August 10, 2016). "Damage in Cleveland Heights caused by microburst". Fox8.com. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Reardon, Kelly (August 10, 2016). "Wind gusts reached 58 mph, lightning struck 10 times a minute in Tuesday's storms". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Higgs, Robert (August 11, 2016). "About 4,000 customers, mostly in Cleveland Heights, still without power from Tuesday's storms". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ Evbouma, Andrei (July 12, 2012). "Storm Knocks Out Power to 206,000 in Chicago Area". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ Gorman, Tom. "8 injured at Nellis AFB when aircraft shelters collapse in windstorm - Thursday, Sept. 8, 2011 | 9 p.m.". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ↑ "Microbursts reported in Hegewisch, Wheeling". Chicago Breaking News. 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ↑ "New York News, Local Video, Traffic, Weather, NY City Schools and Photos - Homepage - NY Daily News". Daily News. New York.

- ↑ "Power Restored to Tornado Slammed Residents: Officials". NBC New York. 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ↑ http://www.newsplex.com/news/headlines/97104629.html and http://www.nbc29.com/Global/story.asp?S=12705577

- ↑ Brian Kushida (2010-06-11). "Strong Winds Rip Through SF Neighborhood - News for Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa". Keloland.com. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ↑ Gasper, Christopher L. (May 6, 2009). "Their view on matter: Patriots checking practice facility". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ "One year after microburst, recovery progresses" KU.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

Bibliography

- Fujita, T. T. (1981). "Tornadoes and Downbursts in the Context of Generalized Planetary Scales". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 38 (8).

- Wilson, James W. and Roger M. Wakimoto (2001). "The Discovery of the Downburst - TT Fujita's Contribution". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 82 (1).

External links

- The Semi-official Microburst Handbook Homepage (NOAA)

- Taming the Microburst Windshear (NASA)

- Microbursts (University of Wyoming)

- Forecasting Microbursts & Downbursts (Forecast Systems Laboratory)