Mihajlo Pupin

| Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin | |

|---|---|

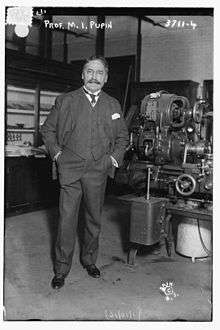

Pupin around 1890 | |

| Born |

9 October 1858 village of Idvor in Banat, Military Frontier, Austrian Empire (now in Serbia) |

| Died |

12 March 1935 (aged 76) New York City, New York, USA |

| Citizenship | Serbian, American |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Fields | Physics, Invention |

| Alma mater | Columbia College |

| Doctoral students | Robert Andrews Millikan, Edwin Howard Armstrong |

| Known for | Long-distance telephone communication |

| Notable awards |

Elliott Cresson Medal (1905) IEEE Medal of Honor (1924)[1] Edison Medal[2] (1920) Pulitzer Prize (1924) John Fritz Medal (1932) |

|

Signature | |

Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin, Ph.D., LL.D. (Serbian Cyrillic: Михајло Идворски Пупин, pronounced [miˈxǎjlo ˈîdʋoɾski ˈpǔpin]; 9 October 1858[3][4] – 12 March 1935), also known as Michael I. Pupin was a Serbian American physicist and physical chemist. Pupin is best known for his numerous patents, including a means of greatly extending the range of long-distance telephone communication by placing loading coils (of wire) at predetermined intervals along the transmitting wire (known as "pupinization"). Pupin was a founding member of National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) on 3 March 1915, which later became NASA.[5]

Early life and education

Mihajlo Pupin was born on 9 October (27 September, OS) 1858 in the village of Idvor (in the modern-day municipality of Kovačica, Serbia) in Banat, in the Military Frontier in the Austrian Empire. He always remembered the words of his mother and cited her in his autobiography, From Immigrant to Inventor (1925):

| “ | My boy, If you wish to go out into the world about which you hear so much at the neighborhood gatherings, you must provide yourself with another pair of eyes; the eyes of reading and writing. There is so much wonderful knowledge and learning in the world which you cannot get unless you can read and write. Knowledge is the golden ladder over which we climb to heaven; knowledge is the light which illuminates our path through this life and leads to a future life of everlasting glory.[6] | ” |

Pupin went to elementary school in his birthplace, to Serbian Orthodox school, and later to German elementary school in Perlez. He enrolled in high school in Pančevo, and later in the Real Gymnasium. He was one of the best students there; a local archpriest saw his enormous potential and talent, and influenced the authorities to give Pupin a scholarship.

Because of his activity in the "Serbian Youth" movement, which at that time had many problems with Austro-Hungarian police authorities, Pupin had to leave Pančevo. In 1872, he went to Prague, where he continued the sixth and first half of the seventh year. After his father died in March 1874, the sixteen-year-old Pupin decided to cancel his education in Prague due to financial problems and to move to the United States.

| “ | When I landed at Castle Garden, forty-eight years ago, I had only five cents in my pocket. Had I brought five hundred dollars, instead of five cents, my immediate career in the new, and to me perfectly strange, land would have been the same. A young immigrant such as I was then does not begin his career until he has spent all the money which he has brought with him. I brought five cents, and immediately spent it upon a piece of prune pie, which turned out to be a bogus prune pie. It contained nothing but pits of prunes. If I had brought five hundred dollars, it would have taken me a little longer to spend it, mostly upon bogus things, but the struggle which awaited me would have been the same in each case. It is no handicap to a boy immigrant to land here penniless; it is not a handicap to any boy to be penniless when he strikes out for an independent career, provided that he has the stamina to stand the hardships that may be in store for him.[7] | ” |

Studies in America and Ph.D

For the next five years in the United States, Pupin worked as a manual laborer (most notably at the biscuit factory on Cortlandt Street in Manhattan) while he learned English, Greek and Latin. He also gave private lectures. After three years of various courses, in the autumn of 1879 he successfully finished his tests and entered Columbia College, where he became known as an exceptional athlete and scholar. A friend of Pupin's predicted that his physique would make him a splendid oarsman, and that Columbia would do anything for a good oarsman. A popular student, he was elected president of his class in his Junior year. He graduated with honors in 1883 and became an American citizen at the same time.

He obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Berlin under Hermann von Helmholtz and in 1889 he returned to Columbia University to become a lecturer of mathematical physics in the newly formed Department of Electrical Engineering. Pupin's research pioneered carrier wave detection and current analysis.[8]

Pupin completed his studies in 1883 as one of the best students, especially in the field of physics and mathematics, which gave him a diploma. Later, he went back to Europe, initially the United Kingdom (1883–1885), where he continued his schooling at the University of Cambridge. He was an early investigator into X-ray imaging, but his claim to have made the first X-ray image in the United States is incorrect.[9] He learned of Röntgen's discovery of unknown rays passing through wood, paper, insulators, and thin metals leaving traces on a photographic plate, and attempted this himself. Using a vacuum tube, which he had previously used to study the passage of electricity through rarefied gases, he made successful images on 2 January 1896. Edison provided Pupin with a calcium tungstate fluoroscopic screen which, when placed in front of the film, shortened the exposure time by twenty times, from one hour to a few minutes. Based on the results of experiments, Pupin concluded that the impact of primary X-rays generated secondary X-rays. With his work in the field of X-rays, Pupin gave a lecture at the New York Academy of Sciences. He was the first person to use a fluorescent screen to enhance X-rays for medical purposes. A New York surgeon, Dr. Bull, sent Pupin a patient to obtain an X-ray image of his left hand prior to an operation to remove lead shot from a shotgun injury. The first attempt at imaging failed because the patient, a well-known lawyer, was "too weak and nervous to be stood still nearly an hour" which is the time it took to get an X-ray photo at the time. In another attempt, the Edison fluorescent screen was placed on a photographic plate and the patient's hand on the screen. X-rays passed through the patients hand and caused the screen to fluoresce, which then exposed the photographic plate. A fairly good image was obtained with an exposure of only a few seconds and showed the shot as if "drawn with pen and ink." Dr. Bull was able to take out all of the lead balls in a very short time.[10][11]

Pupin coils

Pupin's 1899 patent for loading coils, archaically called "Pupin coils", followed closely on the pioneering work of the English physicist and mathematician Oliver Heaviside, which predates Pupin's patent by some seven years. The importance of the patent was made clear when the American rights to it were acquired by American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), making him wealthy. Although AT&T bought Pupin's patent, they made little use of it, as they already had their own development in hand led by George Campbell and had up to this point been challenging Pupin with Campbell's own patent. AT&T were afraid they would lose control of an invention which was immensely valuable due to its ability to greatly extend the range of long distance telephones and especially submarine ones.[12]

Research during the First World War

When the United States joined the First World War in 1917, Pupin was working at Columbia University, organizing a research group for submarine detection techniques.[13] Together with his colleagues, professors Wils and Morcroft, he performed numerous researches with the aim of discovering submarines at Key West and New London. He also conducted research in the field of establishing telecommunications between places. During the war Pupin was a member of the state council for research and state advisory board for aeronautics. For his work he received a laudative from president Warren G. Harding, which was published on page 386 of his autobiography.[14]

Contributions to determining borders of Yugoslavia

In 1912, the Kingdom of Serbia named Pupin an honorary consul in the United States. Pupin performed his duties until 1920. During the First World War, Pupin met with Cecil Spring Rice, the British ambassador to the United States, in an attempt to aid Austro-Hungarian Slavs in Canadian custody. Canada had incarcerated some 8,600 so-called Austrians and Hungarians who were deemed to be a threat to national security and were sent to internment camps across the country. The majority, however, turned out to be Ukrainian, but among them were hundreds of Austro-Hungarian Slavs, including Serbs. The British ambassador agreed to allow Pupin to send delegates to visit Canadian internment camps and accept their recommendation of release. Pupin went on to make great contributions to the establishment of international and social relations between the Kingdom of Serbia, and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the United States.

After World War I, Pupin was already a well-known and acclaimed scientist, as well as a politically influential figure in America. He influenced the final decisions of the Paris peace conference when the borders of the future kingdom (of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians) were drawn. Pupin stayed in Paris for two months during the peace talk (April–May 1919) on the insistence of the government.[15]

| “ | My home town is Idvor, but this fact says little because Idvor can’t be found on the map. That is a small village which is found near the main road in Banat, which belonged to Austro-Hungary, and now is an important part of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians Kingdom. This province on the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, was requested by the Romanians, but their request was invalid. They could not negate the fact that the majority of the inhabitants were Serbs, especially in the Idvor area. President Wilson and Mr. Lancing knew me personally and when found out that I was originally from Banat, Romanian reasons lost its weight.[16] | ” |

According to the London agreement from 1915. it was planned that Italy should get Dalmatia. After the secret London agreement France, England and Russia asked from Serbia some territorial concessions to Romania and Bulgaria. Romania should have gotten Banat and Bulgaria should have gotten a part of Macedonia all the way to Skoplje.[15]

In a difficult situation during the negotiations on the borders of Yugoslavia, Pupin personally wrote a memorandum on 19 March 1919 to American president Woodrow Wilson, who, based on the data received from Pupin about the historical and ethnic characteristics of the border areas of Dalmatia, Slovenia, Istria, Banat, Međimurje, Baranja and Macedonia, stated that he did not recognize the London agreement signed between the allies and Italy.

Mihajlo Pupin foundation

In 1914, Pupin formed "Fund Pijade Aleksić-Pupin" within the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts[17] to commemorate his mother Olimpijada for all the support she gave him through life. Fund assets were used for helping schools in old Serbia and Macedonia, and scholarships were awarded every year on the Saint Sava day. One street in Ohrid was named after Mihajlo Pupin in 1930 to honour his efforts. He also established a separate "Mihajlo Pupin fund" which he funded from his own property in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which he later gave to "Privrednik" for schooling of young people and for prizes in "exceptional achievements in agriculture", as well as for Idvor for giving prizes to pupils and to help the church district.[18]

Thanks to Pupin’s donations, the library in Idvor got a reading room, schooling of young people for agriculture sciences was founded, as well as the electrification and waterplant in Idvor.[19] Pupin established a foundation in the museum of Natural History and Arts in Belgrade. The funds of the foundation were used to purchase artistic works of Serbian artists for the museum and for the printing of certain publications. Pupin invested a million dollars in the funds of the foundation.[18]

In 1909, he established one of the oldest Serbian emigrant organizations in the United States called "Union of Serbs - Sloga." The organization had a mission to gather Serbs in immigration and offer help, as well as keeping ethnic and cultural values. This organization later merged with three other immigrant societies.[20]

Other emigrant organizations in to one large Serbian national foundation, and Pupin was one of its founders and a longtime president (1909–1926)).

He also organized "Kolo srpskih sestara" (English: Circle of Serbian sisters) who gathered help for the Serbian Red Cross, and he also helped the gathering of volunteers to travel to Serbia during the First World War with the help of the Serbian patriotic organization called the "Serbian National Defense Council" which he founded and led. Later, at the start of the Second World War this organization was rehabilitated by Jovan Dučić and worked with the same goal. Pupin guaranteed the delivery of food supplies to Serbia with his own resources, and he also was the head of the committee that provided help to the victims of war. He also founded the Serbian society for helping children which provided medicine, clothes and shelter for war orphans.[21]

Literary work

Besides his patents he published several dozen scientific disputes, articles, reviews and a 396-page autobiography under the name Michael Pupin, From Immigrant to Inventor (Scribner's, 1923).[22] He won the annual Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.[23][24] It was published in Serbian in 1929 under the title From pastures to scientist (Od pašnjaka do naučenjaka).[25] Beside this he also published:

- Pupin Michael: Der Osmotische Druch und Seine Beziehung zur Freien Energie, Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doctorwurde, Buchdruckerei von Gustav Shade, Berlin, June, 1889.

- Pupin Michael: Thermodynamics of Reversible Cycles in Gases and Saturated Vapors, John Wiley & Sons. 1894.

- Pupin Michael: Serbian Orthodox Church, J. Murray. London, 1918.

- Pupin Michael: Yugoslavia. (In Association for International Conciliation Amer. Branch —Yugoslavia). American Association for International Conciliation. 1919.

- Pupin Michael: The New Reformation; from Physical to Spiritual Realities, Scribner, New York, 1927.

- Pupin Michael: Romance of the Machine, Scribner, New York, 1930.

- Pupin Michael: Discussion by M. Pupin and other prominent engineers in Toward Civilization, edited by C. A. Beard. Longmans, Green & Co. New York, 1930.

Pupin Hall

Columbia University's Physical Laboratories building, built in 1927, is named Pupin Hall in his honor. It houses the physics and astronomy departments of the university. During Pupin's tenure, Harold C. Urey, in his work with the hydrogen isotope deuterium demonstrated the existence of heavy water, the first major scientific breakthrough in the newly founded laboratories (1931). In 1934 Urey was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the work he performed in Pupin Hall related to his discovery of "heavy hydrogen".[26]

Patents

Pupin released about 70 technical articles and reviews[27] and 34 patents.[28]

| Number of patent | Date |

|---|---|

| U.S. Patent 519,346 Apparatus for telegraphic or telephonic transmission | 8 May 1894 |

| U.S. Patent 519,347 Transformer for telegraphic, telephonic or other electrical systems | 8 May 1894 |

| U.S. Patent 640,515 Art of distributing electrical energy by alternating currents | 2 January 1900 |

| U.S. Patent 640,516 Electrical transmission by resonance circuits | 2 January 1900 |

| U.S. Patent 652,230 Art of reducing attenuation of electrical waves and apparatus therefore | 19 June 1900 |

| U.S. Patent 652,231 Method of reducing attenuation of electrical waves and apparatus therefore | 19 June 1900 |

| U.S. Patent 697,660 Winding-machine | 15 April 1902 |

| U.S. Patent 707,007 Multiple telegraphy | 12 August 1902 |

| U.S. Patent 707,008 Multiple telegraphy | 12 August 1902 |

| U.S. Patent 713,044 Producing asymmetrical currents from symmetrical alternating electromotive process | 4 November 1902 |

| U.S. Patent 768,301 Wireless electrical signalling | 23 August 1904 |

| U.S. Patent 761,995 Apparatus for reducing attenuation of electric waves | 7 June 1904 |

| U.S. Patent 1,334,165 Electric wave transmission | 16 March 1920 |

| U.S. Patent 1,336,378 Antenna with distributed positive resistance | 6 April 1920 |

| U.S. Patent 1,388,877 Sound generator | 3 December 1921 |

| U.S. Patent 1,388,441 Multiple antenna for electrical wave transmission | 23 December 1921 |

| U.S. Patent 1,415,845 Selective opposing impedance to received electrical oscillation | 9 May 1922 |

| U.S. Patent 1,416,061 Radio receiving system having high selectivity | 10 May 1922 |

| U.S. Patent 1,456,909 Wave conductor | 29 May 1922 |

| U.S. Patent 1,452,833 Selective amplifying apparatus | 24 April 1923 |

| U.S. Patent 1,446,769 Aperiodic pilot conductor | 23 February 1923 |

| U.S. Patent 1,488,514 Selective amplifying apparatus | 1 April 1923 |

| U.S. Patent 1,494,803 Electrical tuning | 29 May 1923 |

| U.S. Patent 1,503,875 Tone producing radio receiver | 29 April 1923 |

Honors and tributes

- President of the Institute of Radio Engineers, USA (1917)

- President of American Institute of Electrical Engineers (1925–26).

- President of American Association for the Advancement of Sciences

- President of New York Academy of Sciences

- Honorary member of German Electrical Society

- Honorary member of American Institute of Electrical Engineers

- Member of National Academy of Sciences

- Member of French Academy of Sciences

- Member of Serbian Academy of sciences

- Member of American Mathematical Society

- Member of American Philosophical Society

- Member of American Physical Society

- Titles

- Doctor of science, Columbia University (1904)

- Honorable doctor of science, Johns Hopkins University (1915)

- Doctor of science, Princeton University (1924)

- Honorable doctor of science, New York University (1924)

- Honorable doctor of science, Muhlenberg College (1924)

- Doctor of engineering, Case School of Applied Science (1925)

- Doctor of science, George Washington University (1925)

- Doctor of science, Union College (1925)

- Honorable doctor of science, Mariette College (1926)

- Honorable doctor of science, University of California (1926)

- Doctor of science, Rutgers University (1926)

- Honorable doctor of science, Delaware University (1926)

- Honorable doctor of science, Canyon College (1926)

- Doctor of science, Brown University (1927)

- Doctor of science, Rochester University (1927)

- Honorable doctor of science, Middlebury College (1928)

- Doctor of science, University in Belgrade (1929)

- Doctor of science, University in Prague (1929)

- Medals

- Eliot Kresson Medal of Franklin Institute (1902)

- Herbert award of French academy (1916)

- Edison's medal of American Institute of Electrical Engineers (1919)

- Honorable medal of American radio institute (1924)

- Honorable medal of institute of social sciences (1924)

- Prize George Washington from western association of engineers (1928)

- White eagle, first degree, Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929)

- White lion, first degree, the greatest medal of Czech-Slovakia (1929)

- Medal John Fritz, four American national association engineers electromechanics (1931)[17]

- Other

- Pupin was pictured on the old 50 million Yugoslav dinar banknote.

- Home page world web browser Google has been dedicated on 9 October 2011, to 157th birth anniversary of scientist Mihajlo Pupin. On the drawing in honor of the Pupin birth symbolically represented as a boy and a girl with two different hills talking on the phone.[31]

- The Central Radio Institute was renamed the Telecommunication and Automation Institute "Mihailo Pupin" in his honor in 1956.[32]

- A small lunar impact crater, in the eastern part of the Mare Imbrium, was named in his honor.[33]

- He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1926 to 1929.

- Honorary citizen, city of Zrenjanin [34] and Municipality of Bled[35]

- Various streets and schools across Serbia are named after him; Boulevard of Mihajlo Pupin (in capital city, Belgrade) or tenth Belgrade gymnasium - Mihajlo Pupin, being the most famous examples.

- A road bridge over the Danube River in Belgrade was named Pupin Bridge in his honor after the vote of the citizens.

Private life

After going to America, he changed his name to Michael Idvorsky Pupin, stressing his origin. His father was named Constantine and mother Olimpijada and Pupin had four brothers and five sisters. In 1888 he married American Sarah Catharine Jackson from New York, with whom he had a daughter named Barbara. They were married only for eight years, because she died from pneumonia.

Pupin had a reputation not only as a great scientist but also a great person. He was known for his manners, great knowledge, love of his homeland and availability to everyone. Pupin was a great philanthropist and patron of the arts. He was a devoted Orthodox Christian and a prominent Freemason.

Mihajlo Pupin died in New York City in 1935 at age 76 and was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx.

Legacy

He is included in The 100 most prominent Serbs.

See also

Notes

- ↑ IEEE Global History Network (2011). "IEEE Medal of Honor". IEEE History Center. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ IEEE Global History Network (2011). "IEEE Edison Medal". IEEE History Center. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ Although Pupin's birth year is sometimes given as 1854 (and Serbia and Montenegro issued a postage stamp in 2004 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his birth), peer-reviewed sources list his birth year as 1858. See:

- Daniel Martin Dumych, "Pupin, Michael Idvorsky (4 Oct. 1858 – 12 Mar. 1935)," American National Biography Online, Oxford University Press, 2005. Accessed 11 March 2008.

- Bergen Davis, "Biographical Memoir of Michael Idvorksy Pupin", National Academy of Sciences of the United States Biographical Memoirs, tenth memoir of volume XIX (1938), pp. 307-323. Accessed 11 March 2008.

- According to Pupin's obituary notice in the New York Times, (14 March 1935, p. 21), he died "in his 77th year." Accessed via ProQuest, 11 March 2008.

- ↑ The Tesla Memorial Society tribute webpage, though dedicated to a "150 years" birthday celebration in 2004, includes a photo of Pupin's gravestone showing the dates 4 October 1858 and 12 March 1935. Accessed 9 October 2011.

- ↑ "NASA - First Meeting". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ Michael I. Pupin's autobiography "From Immigrant to Inventor" (Scribner's, 1925), p. 12

- ↑ From Immigrant to Inventor - Michael Pupin - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. 2005-11-30. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/images/6/6f/Pupin_-_obituaries_for_pupin.pdf

- ↑ Nicolaas A. Rupke, Eminent Lives in Twentieth-Century Science and Religion, page 300, Peter Lang, 2009 ISBN 3631581203.

- ↑ William R. Hendee, E. Russell Ritenour, Medical Imaging Physics, page 227, John Wiley & Sons, 2003 ISBN 047146113X.

- ↑ Pupin, pp.307-308

- ↑ Michael I Pupin (13 Jul 1914). "Serb and Austrian". The Independent. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ "Scientist and inventor - Mihailo Pupin | EEP". Electrical-engineering-portal.com. 2011-04-11. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Pandora Archive". Pandora.nla.gov.au. 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- 1 2 http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0350-3593/2004/0350-35930402071G.pdf

- ↑ From Immigrant to Inventor - Michael Pupin - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "САНУ, Српска академија наука и уметности - Фондови и задужбине". Sanu.ac.rs. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- 1 2 "Zadužbinarstvo - za dobrobit svog naroda | Glas javnosti". Glas-javnosti.rs. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Domovina u srcu | Ostali članci". Novosti.rs. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Vreme 1073 - Atlas naucnika: Sta je meni Mihajlo Pupin". Vreme.com. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Српска народна одбрана у Америци у Првом и Другом светском рату". Snd-us.com. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "From immigrant to inventor". Library of Congress Catalog Record. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ↑ "Biography or Autobiography". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ↑ "Pulitzer Prize - WikiCU, the Columbia University wiki encyclopedia". Wikicu.com. 2012-11-21. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Sa pasnjaka do naucenjaka - Mihajlo Pupin". Gerila.com. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Harold C. Urey - Facts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Биографија Михајла Идворског Пупина

- ↑ Биографија Михајла Пупина на сајту Универзитета Колумбија

- ↑ http://www.mtt-serbia.org.rs/microwave_review/pdf/Vol11No1-02-AMarincic.pdf

- ↑ "Prilozi. : Mihajlo Pupin". Mihajlopupin.info. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Gugl obilježava 157. godinu od rođenja Mihajla Pupina - Vijesti online". Vijesti.me. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Timeline". Institute Mihailo Pupin. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑

- ↑ "Grad Zrenjanin - Počasni građani". Zrenjanin.rs. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Pupin je na Luni, bo tudi na Bledu dobil spomenik?". slovenskenovice.si. 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

Further reading

- Michael Pupin, "From Immigrant to Inventor" (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1924)

- Edward Davis, "Michael Idvorsky Pupin: Cosmic Beauty, Created Order, and the Divine Word." In Eminent Lives in Twentieth-Century Science & Religion, ed. Nicolaas Rupke (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2007), pp. 197–217.

- Bergen Davis: Biographical Memoir of Michael Pupin, National Academy of Sciences of the United States Biographical Memoirs, tenth memoir of volume XIX, New York, 1938.

- Daniel Martin Dumych, Pupin Michael Idvorsky, Oxford University Press, 2005. Accessed 11 March 2008

- Lambić Miroslav: Jedan pogled na život i delo Mihajla Pupina, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, Tehnički fakultet "Mihajlo Pupin", Zrenjanin, 1997.

- S. Bokšan, Mihajlo Pupin i njegovo delo, Naučna izdanja Matice srpske, Novi Sad, 1951.

- S. Gvozdenović, Čikago, Amerika i Vidovdan, Savez Srba u Rumuniji-Srpska Narodna Odbrana, Temišvar-Čikago, 2003.

- J. Nikolić, Feljton Večernjih novosti, galerija srpskih dobrotvora, 2004.

- P. Radosavljević, Idvorski za sva vremena, NIN, Br. 2828, 2005.

- R. Smiljanić, Mihajlo Pupin-Srbin za ceo svet, Edicija – Srbi za ceo svet, Nova Evropa, Beograd, 2005.

- Savo B. Jović, Hristov svetosavac Mihajlo Pupin, Izdavačka ustanova Sv. arh. sinoda, Beograd, 2004.

- Dragoljub A. Cucic, Michael Pupin Idvorsky and father Vasa Zivkovic, 150th Anniversary of the Birth of Mihajlo Pupin, Banja Luka, 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mihajlo Pupin. |

- Mihajlo Pupin at Find a Grave

- Michael Pupin at IEEE History Center

- Pupin's autobiography From Immigrant to Inventor

- ... Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Birth of Michael Pupin ... at Tesla Memorial Society of New York

- Michael Pupin at Library of Congress Authorities, with 23 catalog records