Models of migration to the Philippines

There have been several models of early human migration to the Philippines. Since H. Otley Beyer first proposed his wave migration theory, numerous scholars have approached the question of how, when and why humans first came to the Philippines.

The question of whether the first humans arrived from the south (Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei as suggested by Beyer) or from the north (Yunnan via Taiwan as suggested by the Austronesian theory) has been a subject of heated debate for decades. As new discoveries have come to light, past hypotheses have been reevaluated and new theories constructed.

Beyer's Wave Migration Theory

The most widely known theory of the prehistoric peopling of the Philippines is that of H. Otley Beyer, founder of the Anthropology Department of the University of the Philippines. Heading that department for 40 years, Professor Beyer became the unquestioned expert on Philippine prehistory, exerting early leadership in the field and influencing the first generation of Filipino historians and anthropologists, archaeologists, paleontologists, geologists, and students the world over.[1] According to Dr. Beyer, the ancestors of the Filipinos came in different "waves of migration", as follows:[2]

- "Dawn Man", a cave-man type who was similar to Java man, Peking Man, and other Asian Homo erectus of 250,000 years ago.

- The aboriginal pygmy group, the Negritos, who arrived between 25,000 and 30,000 years ago via land bridges.

- The seafaring tool-using Indonesian group who arrived about 5,000 to 6,000 years ago and were the first immigrants to reach the Philippines by sea.

- The seafaring, more civilized Malays who brought the Iron age culture and were the real colonizers and dominant cultural group in the pre-Hispanic Philippines.

Unfortunately, there is no definite evidence, archaeological or historical, to support this migration theory. On the contrary, the passage of time has made it ever more unlikely. Important problems include his reliance on 19th-century theories of progressive evolution and migratory diffusion that have been shown in other contexts to be overly simplistic and unreliable and his reliance on incomplete archaeological findings and conjecture.[3]

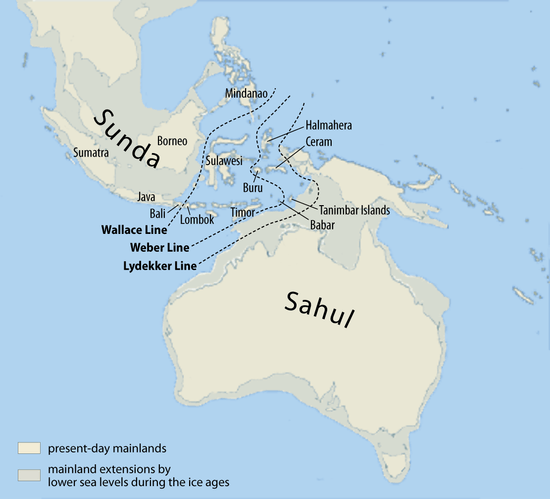

His claims that the Malays were the original settlers of the lowland regions and the dominant cultural transmitter now seem untenable, no subsequent evidence has emerged to support his "Dawn Man",[3] and improved bathymetric soundings have established that there was almost certainly not a land bridge to Sundaland,[4] although most of the islands were connected and could be accessed across the Mindoro Strait and Sibutu Passage. Writing in 1994, Philippine historian William Scott concluded that "it is probably safe to say that no anthropologist accepts the Beyer Wave Migration Theory today."[5]

A German scientist who has studied the Philippines, Fritjof Voss, has even argued that the present soundings are probably a generous overestimate of the earlier situation, as the Philippines have steadily risen over known geologic history.

Core Population Theory

A less rigid version of the earlier wave migration theory is the Core Population Theory first proposed by anthropologist Felipe Landa Jocano of the University of the Philippines.[6] This theory holds that there weren't clear discrete waves of migration. Instead it suggests early inhabitants of Southeast Asia were of the same ethnic group with similar culture, but through a gradual process over time driven by environmental factors, differentiated themselves from one another.[7][8][9]

Jocano contends that what fossil evidence of ancient men show is that they not only migrated to the Philippines, but also to New Guinea, Borneo, and Australia. He says that there is no way of determining if they were Negritos at all. However, what is sure is that there is evidence the Philippines was inhabited tens of thousands of years ago. In 1962, a skull cap and a portion of a jaw, presumed to be those of a human being, were found in Tabon Cave in Palawan.[10]

The nearby charcoal from cooking fires have been dated to c. 22,000 years ago. While Palawan was connected directly to Sundaland during the last ice age (and separated from the rest of the Philippines by the Mindoro Strait), Callao Man's still-older remains (c. 67,000 B.P.) were discovered in northern Luzon. Some have argued that this may show settlement of the Philippines earlier than that of the Malay Peninsula.[10]

Jocano further believes that the present Filipinos are products of the long process of cultural evolution and movement of people. This not only holds true for Filipinos, but for the Indonesians and the Malays of Malaysia, as well. No group among the three is culturally or genetically dominant. Hence, Jocano says that it is not correct to attribute the Filipino culture as being Malayan in orientation.[6]

According to Jocano's findings, the people of the prehistoric islands of Southeast Asia were of the same population as the combination of human evolution that occurred in the islands of Southeast Asia about 1.9 million years ago. The claimed evidence for this is fossil material found in different parts of the region and the movements of other people from the Asian mainland during historic times. He states that these ancient men cannot be categorized under any of the historically identified ethnic groups (Malays, Indonesians, and Filipinos) of today.[6]

Other prominent anthropologists like Robert Bradford Fox, Alfredo E. Evangelista, Jesus Peralta, Zeus A. Salazar, and Ponciano L. Bennagen agreed with Jocano.[9][11] Some still preferred Beyer's theory as the more acceptable model, including anthropologist E. Arsenio Manuel.[9]

Diffusion of Austronesian languages

Another, more contemporary theory based on the study of the evolution of languages suggests that starting 4000–2000 BC, Austronesian groups descended from Yunnan Plateau in China and settled in what is now the Philippines by sailing using balangays or by traversing land bridges coming from Taiwan. Many of these Austronesians settled on the Philippine islands and became the ancestors of the present-day Filipinos and later colonizing most of the Pacific islands and Indonesia to the south.

The Cagayan valley of northern Luzon contains large stone tools as evidence for the hunters of the big game of the time: the elephant-like stegodon, rhinoceros, crocodile, tortoise, pig and deer. The Austronesians pushed the Negritos to the mountains, while they occupied the fertile coastal plains.

Solheim's hypothesis

Anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II posited an alternative model based on maritime movement of people over different directions and routes. It suggests that people with distant origins from 50,000 years ago in the area of present-day coastal eastern Vietnam and Southern China had moved to the area of the Bismarck Islands south and east of Mindanao and developed Pre-Austronesian. Proto-Austranesian then later developed and spread among seafarers from the area to the rest of Island Southeast Asia and areas along the South China Sea. In support of this idea Solheim notes there is little or no indication that Pre- or Proto Malayo-Polynesian was present in Taiwan. According to Solheim, "The one thing I feel confident in saying is that all native Southeast Asians are closely related culturally, genetically and to a lesser degree linguistically."[12]

New developments

The "out of Taiwan" model based on Austronesian linguistic evidence that had become the mainstream explanation is in turn being challenged by newer findings. Studies based on mitochondrial DNA show greater genetic diversity in southern regions than in northern ones suggesting that a significant migration wave was in a south-to-north direction. Older populations entered Southeast Asia first following the coastal regions from Africa then slowly spread north to populate East Asia.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Zaide 1999, p. 32, citing Beyer Memorial Issue on the Prehistory of the Philippines in Philippine Studies, Vol. 15:No. 1 (January 1967).

- ↑ Zaide 1999, pp. 32–34.

- 1 2 Zaide 1999, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Scott 1984, pp. 1 and Map 2 in Frontispiece

- ↑ Scott, William H. Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society, p. 11. Manila University Press (Manila), 1994. ISBN 971-550-135-4. Accessed 14 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 Antonio; et al. (2007). Turning Points I. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 65. ISBN 978-971-23-4538-8.

- ↑ Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History. Rex Bookstore. pp. 34–35. ISBN 971-23-3934-3. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ Rowthorn, Chris, Monique Choy, Michael Grosberg, Steven Martin, and Sonia Orchard. (2003). Philippines (8th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 12. ISBN 1-74059-210-7. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- 1 2 3 Samuel K. Tan (2008). A History of the Philippines. UP Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-971-542-568-1.

- 1 2 Rosario S. Sagmit & Nora N. Soriano (1998). Geography in the Changing World. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 978-971-23-2451-2.

- ↑ S. Lily Mendoza (2001). "Nuancing Anti-Essentialism: A Critical Genealogy of Philippine Experiments in National Identity Formation". In Lisa C. Bower; David Theo Goldberg. Between law and culture: relocating legal studies. University of Minnesota Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-8166-3380-7.

- ↑ Solheim II, Wilhelm G. (January 2006). Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-03. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ New DNA evidence overturns population migration theory in Island Southeast Asia. (May 23, 2008). Oxford University. Retrieved March 3, 2011 from PhysOrg.com.

- ↑ Genetic study uncovers new path to Polynesia. (February 3, 2011). Leeds University. Retrieved March 3, 2011 from PhysOrg.com.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul. (October 5, 2006). Early humans followed the coast. BBC News. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ↑ Genetic 'map' of Asia's diversity. (December 11, 2009). BBC News. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ↑ Soares, Pedro, Jean Alain Trejaut, Jun-Hun Loo, Catherine Hill, Maru Mormina, Chien-Liang Lee, Yao-Ming Chen, Georgi Hudjashov, Peter Forster, Vincent Macaulay, David Bulbeck; et al. (2008-03-21). "Climate Change and Postglacial Human Dispersals in Southeast Asia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 25 (6): 1209–1218. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn068. PMID 18359946. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) Pan-Asian SNP Consortium. (2009-12-11). "Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia". Science. 326 (5959): 1541–1545. doi:10.1126/science.1177074. PMID 20007900. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ Soares, Pedro, Teresa Rito, Jean Trejaut, Maru Mormina, Catherine Hill, Emma Tinkler-Hundal, Michelle Braid, Douglas J. Clarke, Jun-Hun Loo; et al. (2011-02-11). "Ancient Voyaging and Polynesian Origins". American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (2): 239–247. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.009. PMC 3035714

. PMID 21295281. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

. PMID 21295281. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

References

- Scott, William Henry (1984), Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History, New Day Publishers, ISBN 971-10-0226-4, retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1999), The Philippines: A Unique Nation (Second ed.), All-Nations Publishing, ISBN 971-642-071-4.

Further reading

- Bellwood, Peter S., James J. Fox, and Darrell T. Tryon. (Eds.). (1995). The Austronesians – Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Department of Anthropology as part of the Comparative Austronesian Project, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0-7315-1578-1. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Jocano, F. Landa (1975), Philippine Prehistory: An Anthropological Overview of the Beginnings of Filipino Society and Culture, Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines System

- Oppenheimer, Stephen (1999), Eden in the East – The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia, Phoenix, ISBN 0-7538-0679-7.

- Regalado, Felix B; Franco, Quintin B. (1973), Grimo, Eliza B., ed., History of Panay, Central Philippine University

- Scott, William Henry (1992), Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino, Quezon City: New Day Publishers, ISBN 971-10-0524-7.