Piracy in the Sulu Sea

Piracy in the Sulu Sea occurred in the vicinity of Mindanao, where frequent acts of piracy were committed against the Spanish. Because of the continual wars between Spain and the Moro people, the areas in and around the Sulu Sea became a haven for piracy which was not suppressed until the beginning of the 20th century. The pirates should not be confused with the naval forces or privateers of the various Moro tribes. However, many of the pirates operated under government sanction during time of war.[1][2]

Ships

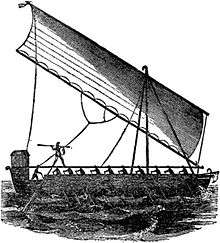

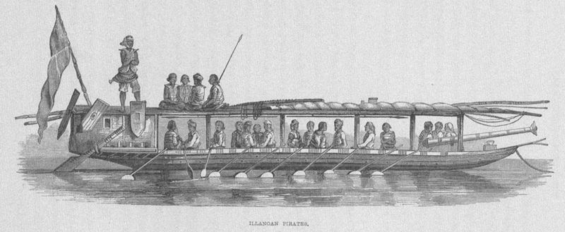

The pirate ships used by the Moros were known as proa, or garays, and they varied in design. The majority were wooden sailing galleys about ninety feet long with a beam of ten feet 27.4 by 6.1 m. They carried around fifty to 100 crewmen. Moros usually armed their vessels with three swivel guns, called lelahs or lantakas, and occasionally a heavy cannon, proas were very fast and the pirates would prey on merchant ships becalmed in shallow water as they passed through the Sulu Sea. Slave trading and raiding was also very common, the pirates would assemble large fleets of proas and attack coastal towns. Hundreds of Christians were captured and imprisoned over the centuries, many were used as galley slaves aboard the pirate ships.[3][4]

Weapons

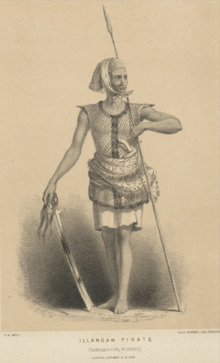

Other than muskets and rifles, the Moro pirates, as well as the navy sailors and the privateers, used a sword called the kris with a wavy blade incised with blood channels. The wooden or ivory handle was often heavily ornamented with silver or gold. The type of wound inflicted by its blade makes it difficult to heal. The kris was used often used in boarding a vessel. Moros also used a Kampilan, another sword, a knife, or barong and a spear, made of bamboo and an iron spearhead. The Moro's swivel guns were not like more modern guns used by the world powers but were of a much older technology, making them largely inaccurate, especially at sea. Lantakas dated back to the 16th century and were up to six feet long, requiring several men to lift one. They fired up to a half-pound cannonball or grape shot. A lantaka was bored by hand and were sunk into a pit and packed with dirt to hold them in a vertical position. The barrel was then bored by a company of men walking around in a circle to turn drill bits by hand.[2]

History

The Spanish engaged the Moro pirates frequently in the 1840s. The expedition to Balanguingui in 1848 was commanded by Brigadier José Ruiz with a fleet of nineteen small warships and hundreds of Spanish Army troops. They were opposed by at least 1,000 Moros holed up in four forts with 124 cannons and plenty of small arms. There were also dozens of proas at Balanguingui but the pirates abandoned their ships for the better defended fortifications. The Spanish stormed three of the positions by force and captured the remaining one after the pirates had retreated. Over 500 prisoners were freed in the operation and over 500 Moros were killed or wounded, they also lost about 150 proas. The Spanish lost twenty-two men killed and around 210 wounded. The pirates later reoccupied the island in 1849: another expedition was sent which encountered only light resistance.

According to a legend, the Rungus in Sabah also fought a battle to protect their homeland on the northern tip of Borneo against the Moro pirates in a place later named Tanjung Simpang Mengayau.[5][6] Also in the 1840s, James Brooke became the White Rajah of Sarawak and he led a series of campaigns against the Moro pirates. In 1843 Brooke attacked the pirates of Malludu and in June 1847 he participated in a major battle with pirates at Balanini where dozens of proas were captured or sunk. Brooke fought in several more anti-piracy actions in 1849 as well. During one engagement off Mukah with Illanun Sulus in 1862, his nephew, ex-army Captain Brooke, sank four proas, out of six engaged, by ramming them with his small four-gun steamship Rainbow. Each pirate ship had over 100 crewmen and galley slaves aboard and was armed with three brass swivel guns. Brooke lost only a few men killed or wounded while at least 100 pirates were killed or wounded. Several prisoners were also released.[4][7] As recently as 1985, pirates caused chaos in the town of Lahad Datu in Sabah, killing 21 people and injuring 11 others.[8][9]

On 17 October 2014, 10 Vietnamese fishermen working for Malay employer were attacked by Filipino pirates.[10] In late 2015, a Vietnamese fisherman was killed by Filipino pirates in South China Sea after the pirates reaching there to expanding their activities.[11]

Gallery

-

Piratical Proa in Full Chase

-

Moro proa armed with a lantaka at the bow

-

Sulu pirate

-

James Brooke's engages pirates off Sarawak

-

Spanish warships bombarding the Moro pirates of Balanguingui in 1848

-

The Spanish landing at Balanguingui by Antonio Brugada

-

Kris from Java

-

19th century barong from the Sulu Archipelago

See also

- Timawa

- Barbary Pirates

- Caribbean Pirates

- Spanish–Moro conflict

- Philippine-American War

- Cross border attacks in Sabah

References

- ↑ Root 1902, pp. 383-397.

- 1 2 Hurley 1936.

- ↑ Scholz 2006.

- 1 2 McDougall 1882.

- ↑ Ena 2012.

- ↑ Kleinen & Osseweijer 2010, p. 229.

- ↑ Sala & Yates 1868.

- ↑ New Straits Times 1987.

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald 1985.

- ↑ Filipino pirates shoot Vietnamese fishermen off Malay coast Thanh Nien News. 17 October 2014. Retrieved on 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Trung Nguyen (1 December 2015). "Killing of Vietnamese Fisherman in Contested Waters Sparks Outrage". Voice of America. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

Earlier Phan Huy Hoang, chairman of Quang Ngai Association of Fisheries, said the fishermen told him that Philippine bandits might be involved in the case. For sure, they are foreign attackers, but their nationality is not known yet.

* "Fishing association claims Filipino boat crew shot dead Vietnamese fisherman". Dantri News International. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

* "Vietnam orders investigation into shooting death of fisherman in Vietnamese waters". Tuổi Trẻ. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2016.A local fishery association has said the murderers were Filipinos.

Sources

- Ena (9 July 2012). "Heaven at the edge of Borneo". Tourism Malaysia. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- Hurley, Vic (Gerald Victor) (1936) [2010]. Swish of the Kris, The Story of the Moros (PDF). Christopher L. Harris 2010. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. ISBN 978-0615382425. OCLC 1837416.

- Kleinen, John & Osseweijer, Manon (2010). Pirates, Ports, and Coasts in Asia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Institute of Southeast Asian. p. 229. ISBN 978-9814279079.

- McDougall, Harriette (1882) [2015]. "Sketches of Our Life at Sarawak". SPCK. ISBN 978-1511851268. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- New Straits Times, K. P. Waran (24 September 1987). "Lahad Datu Recalls Its Blackest Monday". p. 12. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- Root, Elihu (1902) [2012]. Elihu Root collection of United States documents relating to the Philippine Islands. vol 91 pt 2. US Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1231100561.

- Sala, George Augustus & Yates, Edmund Hodgson (1868) [2011]. "The Career and Character of Rajah Brooke". Temple Bar – A London Magazine for Time and Country Readers. XXIV. Ward and Lock. pp. 204–216. ISBN 978-1173798765. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Scholz, Herman (2006). "Discover Sabah - History". Flyingdusun.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Sydney Morning Herald, Masayuki Doi (30 October 1985). "Filipino pirates wreak havoc in a Malaysian island paradise". p. 11. Retrieved 30 October 2014.