Nekomata

Nekomata (original form: 猫また, later forms: 猫又, 猫股, 猫胯) are a kind of cat yōkai told about in folklore as well as classical kaidan, essays, etc. There are two very different types, the beast that lives in the mountains, and the ones raised domestically that grow old and transform.[1] It is often confused with Bakeneko.

Mountain Nekomata

In China, they are told of in stories even older than in Japan from the Sui dynasty like in 猫鬼 or 金花猫 that told of mysterious cats, but in Japan, in the Meigetsuki by Fujiwara no Teika in the early Kamakura period, in the beginning of Tenpuku (1233), August 2, in Nanto (now Nara Prefecture), there is a statement that a nekomata (猫胯) ate and killed several people in one night. This is the first appearance of the nekomata in literature, and the nekomata was talked about as a beast in the mountains. However, in the "Meigetsuki," concerning their appearance, it was written, "they have eyes like a cat, and have a large body like a dog," there are many who raise the question of whether or not it really is a monster of a cat,[2] and since there are statements that people suffer an illness called the "nekomata disease (猫跨病)," there is the interpretation that it is actually a beast that has caught rabies.[3] Also, in the essay Tsurezuregusa from the late Kamakura period (around 1331), it was written, "in the mountain recesses, there are those called nekomata, and people say that they eat humans... (奥山に、猫またといふものありて、人を食ふなると人の言ひけるに……)."[2][4]

Even the kaidan collections, the "Tonoigusa (宿直草)" and the "Sorori Monogatari (曾呂利物語)," nekomata conceal themselves in the mountain recesses, and there are stories where deep in the mountains they would appear shapeshifted into humans,[5][6] and in folk religion there are many stories of nekomata in mountainous regions.[1] The nekomata of the mountains have a tendency to be larger in later literature, and in the "Shin Chomonjū (新著聞集)," nekomata captured in the mountains of the Kii Province are as large as a wild boar, and in "Wakun no Shiori (倭訓栞)" from 1775 (Anei 4), from the statement that their roaring voice echos throughout the mountain, they can be seen to be as big as a lion or a leopard. In "Gūisō (寓意草)" from 1809 (Bunka 6), a nekomata that held a dog in its mouth had a span of 9 shaku and 5 sn (about 2.8 meters).[2]

In the Etchū Province (now Toyama Prefecture), in Aizu, at the Nekomatayama said to be where nekomata would eat and kill humans (now Fukushima Prefecture), nekomata that shapeshift into humans and fool people, like Mount Nekomadake, sometimes have their legends be named after the name of the mountain.[3] Concerning Nekomatayama, it can be seen that not following folklore at all, there actually are large cats living in the mountain that attack humans.[7]

Domesticated cat Nekomata

At the same time, in the Kokon Chomonjū from the Kamakura period, in the story called Kankyō Hōin (観教法印), an old cat raised in a precipitous mountain villa held in its mouth a secret treasure, a protective sword, and ran away, and people chased after it, but it disguised its appearance right then, and it left behind that the pet cat became a monster, but in the aforementioned "Tsurezuregusa," this is also a nekomata, and it talks about how other than the nekomata that conceal themselves in the mountains, there are also the pet cats that grow old, transform, and eat and abduct people.[4]

In the Edo period and afterwards, it has become generally thought that cats raised domestically would turn into nekomata as they grow old, and the aforementioned nekomata of the mountains have come to be interpreted as cats that have run away and came to live in the mountains. Because of that, a folk belief emerged in each area of Japan that cats are not to be raised for many months and years.[1]

In the "Ansai Zuihitsu (安斎随筆)" by the court ceremonial Sadatake Ise, the statement "a cat that is several years of age will come to have two tails, and become the yōkai called nekomata" can be seen. Also, the mid-Edo period scholar Arai Hakuseki stated, "old cats become 'nekomata' and bewilder people," and indicating it was common sense at that time to think that cats become nekomata, and even the Kawaraban of the Edo period reported on this strange phenomenon.[2]

In the book Yamato Kaiiki (大和怪異記, engl. "Mysterious stories from Japan"), written by an unknown author in 1708, a story speaks about a haunted house of a rich samurai. The inhabitants of this house witness several poltergeist-activities and the samurai invites countless shamans, priests and evokers in attempt to make the happenings come to an end. But none of them is able to find the source of the terror. One day one of the most loyal servants observes his master's very old cat carrying a shikigami with the imprinted name of the samurai in its mouth. Immediately the servant fires a sacred arrow, hitting the cat in its head. When the cat is lying dead on the floor, all inhabitants can see that the cat has two tails and therefore had become a nekomata. With the death of the demon-cat the poltergeist-activities end. Similar eerie stories about encounters with nekomata appear in books such as Taihei Hyakumonogatari (太平百物語, engl. "Collection of 100 fairy tales"), written by Yusuke (祐佐, or Yūsa) in 1723 and in the book Rōō Chabanashi (老媼茶話, "Tea-time gossip of old ladies"), written by Misaka Daiyata (三坂大彌) in 1742.

It is generally said that the "mata" (又) of "nekomata" comes from how they have two tails, but from the view of folkloristics, this is seen as questionable, and since they transform as they grow older, the theory that it is the "mata" meaning "repetition," or as previously stated, since they were once thought to be a beast in the mountains, there is the theory that it comes from "mata" (爰) meaning monkeys, with the meaning that they are like monkeys that can freely come and go between trees in the mountains at will.[8] There is also the theory that it comes from the way in which cats that grow old shed the skin off their backs and hang downwards, making it seem like they have two tails.[9]

Cats are often associated with death in Japan, and this particular spirit is often blamed. Far darker and malevolent than most bakeneko, the nekomata is said to have powers of necromancy, and upon raising the dead, will control them with ritualistic dances - gesturing with paw and tail. These yōkai are associated with strange fires and other unexplainable occurrences. The older, and the more badly treated a cat has been before its transformation, the more power the nekomata is said to have. To gain revenge against those who have wronged it, the spirit may haunt humans with visitations from their dead relatives. Like bakeneko, some tales state how these demons have taken on human appearance - but have usually appeared as older women, behaving badly in public and bringing gloom and malevolence wherever they travelled. Sometimes the tails of kittens were cut off as a precaution as it was thought that if their tails could not fork, they could not become nekomata

From this discernment and strange characteristics, nekomata have been considered devilish ones from time immemorial. Due to fears and folk beliefs such as the dead resurrecting at a funeral, or that seven generations would be cursed as a result of killing a cat, it is thought that the legend of the nekomata was born.[3][10] Also, in folk beliefs cats and the dead are related. As carnivores, cats have a sharp sense of detecting the smell of rotting, and so it was believed that they had a trait of approaching corpses; with this folk belief sometimes the kasha, a yōkai that steals the corpses of the dead, are seen to be the same as the nekomata.[1]

Also in Japan there are cat yōkai called the bakeneko, but since nekomata are certainly the yōkai of transformed cats, sometimes nekomata are confused with bakeneko.[11]

Yōkai depictions

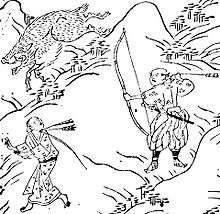

In the Edo period, many in style of illustrated reference books, yōkai emaki, have been made, and nekomata are frequently the subject of these yōkai depictions. In the Hyakkai Zukan published in 1737 (Gembun 2), there was a depiction of a nekomata taking on the appearance of a human female playing a shamisen, but since shamisen in the Edo period were frequently made by using the skins of cats, the nekomata played the shamisen and sang a sad song about its own species,[1] and has been interpreted as a kind of irony etc.[12] Concerning the fact that they wear geisha clothing, there is the viewpoint they are related due to the fact that geisha were once called "cats (neko)"[12] (refer to first image).

Also, in the "Gazu Hyakki Yagyō" published in 1776 (An'ei 5) (refer to image on right), with a depiction of a cat on the left with its head coming out of a shōji, a cat on the right with a handkerchief on its head and its forepaw on the veranda, and a cat in the middle also wearing a handkerchief and standing on two legs, and thus as a cat that has not had enough experience and thus as difficulty standing on two legs, a cat that has grown older and has become able to stand on two legs, it can be seen to be depicting the process by which a normal cat grows older and tramsforms into a nekomata.[12] Also, in the Bigelow collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (the ukiyo-e collection), in the "Hyakki Yagyō Emaki," since pretty much the same composition of nekomata has been depicted, some have pointed out a relation between them.[13]

Senri

In China there is a cat yōkai called "senri (仙狸)" (where 狸 means "leopard cat"). This is where leopard cats that grow old gain a divine spiritual power, and they would shapeshift into a beautiful man or woman and suck the spirit out of humans.[14]

There is the theory that the legends of nekomata of Japan come from tales of the senri.[15]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 多田 (2000)、170-171頁。

- 1 2 3 4 笹間 (1994)、127-128頁。

- 1 2 3 石川 (1986)、696頁。

- 1 2 平岩 (1992)、36-66頁。

- ↑ 荻田安静編著 (1989). "宿直草". In 高田衛編・校中. 江戸怪談集. 岩波文庫. 上. 岩波書店. pp. 121–124. ISBN 978-4-00-302571-0.

- ↑ 編著者不詳 (1989). "曾呂利物語". In 高田衛編・校中. 江戸怪談集. 岩波文庫. 中. 岩波書店. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-4-00-302572-7.

- ↑ 谷川健一 (1998). 続 日本の地名. 岩波新書. 岩波書店. p. 146. ISBN 978-4-00-430559-0.

- ↑ 日野巌 (2006). 動物妖怪譚. 中公文庫. 下. 中央公論新社. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-4-12-204792-1.

- ↑ "ネコのうんちく". カフェ にゃんまる. Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2012-11-03. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ 佐野賢治他 (1980). 桜井徳太郎編, ed. 民間信仰辞典. 東京堂出版. p. 223. ISBN 978-4-490-10137-9.

- ↑ 京極夏彦 (2010). "妖怪の宴 妖怪の匣 第6回". In 郡司聡他編. 怪. カドカワムック. vol.0029. 角川書店. p. 122. ISBN 978-4-04-885055-1.

- 1 2 3 古山他 (2005)、155頁。

- ↑ 湯本豪一編著 (2006). 続・妖怪図巻. 国書刊行会. pp. 161–165. ISBN 978-4-336-04778-6.

- ↑ 新紀元社編集部 (2003). 健部伸明監修, ed. 真・女神転生悪魔事典. Truth In Fantasy. 新紀元社. p. 94. ISBN 978-4-7753-0149-4.

- ↑ 一条真也監修 (2010). 世界の幻獣エンサイクロペディア. 講談社. p. 194. ISBN 978-4-06-215952-4.

References

- 石川純一郎他 (1986). 乾克己他編, ed. 日本伝奇伝説大事典. 角川書店. ISBN 978-4-04-031300-9.

- 笹間良彦 (1994). 図説・日本未確認生物事典. 柏書房. ISBN 978-4-7601-1299-9.

- 多田克己 (2000). 京極夏彦・多田克己編, ed. 妖怪図巻. 国書刊行会. ISBN 978-4-336-04187-6.

- 平岩米吉 (1992). "猫股伝説の変遷". 猫の歴史と奇話. 築地書館. ISBN 978-4-806-72339-4.

- 古山桂子他 (2005). 播磨学研究所編, ed. 播磨の民俗探訪. 神戸新聞総合出版センター. ISBN 978-4-343-00341-6.

- Patrick Drazen: A Gathering of Spirits: Japan's Ghost Story Tradition: from Folklore and Kabuki to Anime and Manga. iUniverse, New York 2011, ISBN 1-4620-2942-6, page 114.

- Elli Kohen: World history and myths of cats. Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston 2003, ISBN 0-7734-6778-5, page 48–51.

- Carl Van Vechten: The Tiger In The House. Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 1-4179-6744-7, page 96.

External links

- web-informations about Nekomata at obakemono.com (English)

- Nekomata – The Split-Tailed Cat at hyakumonogatari.com(English)