Leopard cat

| Leopard cat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Prionailurus |

| Species: | P. bengalensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Prionailurus bengalensis[2] (Kerr, 1792) | |

| |

| Leopard cat range | |

The leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) is a small wild cat native to South, Southeast and East Asia. Since 2002 it has been assessed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List as it is widely distributed but threatened by habitat loss and hunting in parts of its range.[1]

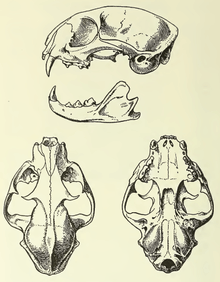

Leopard cat subspecies differ widely in fur colour, tail length, skull shape and size of carnassials.[3]

Characteristics

A leopard cat is about the size of a domestic cat, but more slender, with longer legs and well-defined webs between its toes. Its small head is marked with two prominent dark stripes and a short and narrow white muzzle. There are two dark stripes running from the eyes to the ears, and smaller white streaks running from the eyes to the nose. The backs of its moderately long and rounded ears are black with central white spots. Body and limbs are marked with black spots of varying size and color, and along its back are two to four rows of elongated spots. The tail is about half the size of its head-body length and is spotted with a few indistinct rings near the black tip. The background color of the spotted fur is tawny, with a white chest and belly. However, in their huge range, they vary so much in coloration and size of spots as well as in body size and weight that initially they were thought to be several different species. The fur color is yellowish brown in the southern populations, but pale silver-grey in the northern ones. The black markings may be spotted, rosetted, or may even form dotted streaks, depending on subspecies. In the tropics, leopard cats weigh 0.55 to 3.8 kg (1.2 to 8.4 lb), have head-body lengths of 38.8 to 66 cm (15.3 to 26.0 in), with long 17.2 to 31 cm (6.8 to 12.2 in) tails. In northern China and Siberia, they weigh up to 7.1 kg (16 lb), and have head-body lengths of up to 75 cm (30 in); generally, they put on weight before winter and become thinner until spring.[4] Shoulder height is about 41 cm (16 in).

Leopard cats in the Sundaic region are darker, have smaller spots and shorter tails than leopard cats in mainland Asia.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Leopard cats are the most widely distributed Asian small cats. Their range extends from the Amur region in the Russian Far East over the Korean Peninsula, China, Indochina, the Indian Subcontinent, to the West in northern Pakistan, and to the south in the Philippines and the Sunda islands of Indonesia. They live in tropical evergreen rainforests and plantations at sea level, in subtropical deciduous and coniferous forests in the foothills of the Himalayas at altitudes above 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[4] They are able to tolerate human-modified landscapes with vegetation cover to some degree, and inhabit agriculturally used areas such as oil palm and sugar cane plantations.[5][6]

In 2009, a leopard cat was camera trapped in Nepal's Makalu-Barun National Park at an altitude of 3,254 m (10,676 ft). At least six individuals inhabit the survey area, which is dominated by associations of rhododendron, oak and maple.[7] The highest altitudinal record was obtained in September 2012 at 4,500 m (14,800 ft) in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area.[8]

In the northeast of their range they live close to rivers, valleys and in ravine forests, but avoid areas with more than 10 cm (3.9 in) of snowfall.[9] They are rare in Pakistan's arid treeless areas.[10] In Afghanistan, they were reported in the 1970s from Jalalkot and Norgul in the Kunar Valley, and the Waygul forest of Dare Pech.[11]

In Sabah's Tabin Wildlife Reserve leopard cats had average home ranges of 3.5 km2 (1.4 sq mi).[12] In Thailand's Phu Khieu Wildlife Reserve 20 leopard cats were radio-collared between 1999 and 2003. Home ranges of males ranged from 2.2 km2 (0.85 sq mi) to 28.9 km2 (11.2 sq mi), and of the six females from 4.4 km2 (1.7 sq mi) to 37.1 km2 (14.3 sq mi).[13]

Leopard cats are not found in the Japanese archipelago, but fossils have been excavated there from the Pleistocene period.[14]

Distribution of subspecies

As of 2009, the following subspecies are recognized:[1][15]

- Indian leopard cat P. b. bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) — ranges from India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, to Indochina and Yunnan in China;[16]

- Javan leopard cat P. b. javanensis (Desmarest, 1816) — inhabits Java and Bali;[3]

- Sumatran leopard cat P. b. sumatranus (Horsfield 1821) — inhabits Sumatra and Tebingtinggi;[3]

- Chinese leopard cat P. b. chinensis (Gray 1837) — lives in Taiwan and China except Yunnan;[16]

- Himalayan leopard cat P. b. horsfieldi (Gray 1842) — ranges in Kashmir, Punjab, Kumaon, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan;[16]

- Amur leopard cat P. b. euptilurus/euptilura (Elliott 1871) — is distributed in eastern Siberia, Manchuria, Korea[16] and on the Tsushima Island;[17]

- Bornean leopard cat P. b. borneoensis (Brongersma 1936) — inhabits Borneo;[3]

- P. b. trevelyani (Pocock 1939) — lives in northern Kashmir and Punjab, and in southern Baluchistan;[16]

- Hainan leopard cat P. b. alleni (Sody, 1949) — inhabits Hainan Island

- Iriomote cat P. b. iriomotensis (Imaizumi, 1967) — is found exclusively on the island of Iriomote, one of the Ryukyu Islands in the Japanese Archipelago;[18]

- Palawan leopard cat P. b. heaneyi (Groves 1997) — inhabits the Philippine island of Palawan;[3]

- Visayan leopard cat P. b. rabori (Groves 1997) — inhabits the Philippine islands of Negros, Cebu, and Panay.[3]

The Iriomote cat has been proposed as a species since 1967, but following mtDNA analysis in the 1990s it is now considered a subspecies of the leopard cat.[1][19]

The Tsushima leopard cat (Japanese: Tsushima yamaneko)[20] lives exclusively on Tsushima Island. Initially regarded as belonging to the Chinese leopard cat subspecies, it is now considered an isolated population of the Amur leopard cat, P. b. euptilurus/euptilura.[21]

Ecology and behavior

Leopard cats are solitary, except during breeding season. Some are active during the day, but most hunt at night, preferring to stalk murids, tree shrews and hares. They are agile climbers and quite arboreal in their habits. They rest in trees, but also hide in dense thorny undergrowth on the ground.[13] In the oil palm plantations of Sabah, they have been observed up to 4 m (13 ft) above ground hunting rodents and beetles. In this habitat, males had larger home ranges than females, averaging 3.5 km2 (1.4 sq mi) and 2.1 km2 (0.81 sq mi) respectively. Each male's range overlapped one or more female ranges.[22] There is evidence to suggest that rats are abundant and may be easy to catch in oil palm plantations. [22] There, leopard cats feed on a large proportion of rats compared to forested areas.[5]

Leopard cats can swim, but seldom do so. They produce a similar range of vocalisations to the domestic cat. Both sexes scent mark their territory by spraying urine, leaving faeces in exposed locations, head rubbing, and scratching.[4]

Diet

Leopard cats are carnivorous, feeding on a variety of small prey including mammals, lizards, amphibians, birds and insects. In most parts of their range, small rodents such as rats and mice form the major part of their diet, which is often supplemented with grass, eggs, poultry, and aquatic prey. They are active hunters, dispatching their prey with a rapid pounce and bite. Unlike many other small cats, they do not "play" with their food, maintaining a tight grip with their claws until the animal is dead. This may be related to the relatively high proportion of birds in their diet, which are more likely to escape when released than are rodents.[4]

Reproduction and development

The breeding season of leopard cats varies depending on climate. In tropical habitats, kittens are born throughout the year. In colder habitats farther north, females give birth in spring. Their gestation period lasts 60–70 days. Litter size varies between two and three kittens. Captive born kittens weighed 75 to 130 grams (2.6 to 4.6 oz) at birth and opened their eyes by latest 15 days of age. Within two weeks, they doubled their weight and were four times their birth weight at the age of five weeks. At the age of four weeks, their permanent canines break through, and they begin to eat meat. Captive females reach sexual maturity earliest at the age of one year and have their first litter at the age of 13 to 14 months. Captive leopard cats have lived for up to thirteen years.[4]

The estrus period lasts 5–9 days.

Threats

In China, leopard cats are hunted mainly for their fur. Between 1984 and 1989, about 200,000 skins were exported yearly. A survey carried out in 1989 among major fur traders revealed more than 800,000 skins on stock. Since the European Union imposed an import ban in 1988, Japan has become the main buyer, and imported 50,000 skins in 1989.[23] Although commercial trade is much reduced, the species continues to be hunted throughout most of its range for fur, for food, and as pets. They are also widely viewed as poultry pests and killed in retribution.[1]

In Myanmar, 483 body parts of at least 443 individuals were observed in four markets surveyed between 1991 and 2006. Numbers were significantly larger than non-threatened species. Three of the surveyed markets are situated on international borders with China and Thailand, and cater to international buyers, although the leopard cat is completely protected under Myanmar's national legislation. Implementation and enforcement of CITES is considered inadequate.[24]

Conservation

Prionailurus bengalensis is listed in CITES Appendix II. In Hong Kong, the species is protected under the Wild Animals Protection Ordinance Cap 170. The population is well over 50,000 individuals and, although declining, the cat is not endangered.[1]

The Tsushima leopard cat is listed as Critically Endangered on the Japanese Red List of Endangered Species, and has been the focus of a conservation program funded by the Japanese government since 1995.[21]

In the United States, P. bengalensis is listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act since 1976; except under permit, it is prohibited to import, export, sell, purchase and transport leopard cats in interstate commerce.[25]

Taxonomic history

In 1792, Robert Kerr first described a leopard cat under the binominal Felis bengalensis in his translation of Carl von Linné's Systema Naturae as being native to southern Bengal.[26] Between 1829 and 1922, different authors of 20 more descriptions classified the cat either as Felis or Leopardus.[16] Owing to the individual variation in fur colour, leopard cats from British India were described as Felis nipalensis from Nepal, Leopardus ellioti from the area of Bombay, Felis wagati and Felis tenasserimensis from Tenasserim. In 1939, Reginald Innes Pocock subordinated them to the genus Prionailurus. The collection of the Natural History Museum in London comprised several skulls and large amounts of skins of leopard cats from various regions. Based on this broad variety of skins, he proposed to differentiate between a southern subspecies Prionailurus bengalensis bengalensis from warmer latitudes to the west and east of the Bay of Bengal, and a northern Prionailurus bengalensis horsfieldi from the Himalayas, having a fuller winter coat than the southern. His description of leopard cats from the areas of Gilgit and Karachi under the trinomen Prionailurus bengalensis trevelyani is based on seven skins that had longer, paler and more greyish fur than those from the Himalayas. He assumed that trevelyani inhabits more rocky, less forested habitats than bengalensis and horsfieldi.[27]

Between 1837 and 1930, skins and skulls from China were described as Felis chinensis, Leopardus reevesii, Felis scripta, Felis microtis, decolorata, ricketti, ingrami, anastasiae and sinensis, and later grouped under the trinomen Felis bengalensis chinensis.[16] In the beginning of the 20th century, a British explorer collected wild cat skins on the island of Tsushima. Oldfield Thomas classified these as Felis microtis, which had been first described by Henri Milne-Edwards in 1872.[28]

Two skins from Siberia motivated Daniel Giraud Elliot to write a detailed description of Felis euptilura in 1871. One was depicted in Gustav Radde's illustration cum description of a wild cat; the other was part of a collection at the Regent's Park Zoo. The ground colour of both was light brownish-yellow, strongly mixed with grey and covered with reddish-brown spots, head grey with a dark-red stripe across the cheek.[29] In 1922, Tamezo Mori described a similar but lighter grey spotted skin of a wild cat from the vicinity of Mukden in Manchuria that he named Felis manchurica.[30] Later both were grouped under the trinomen Felis bengalensis euptilura.[16] In the 1970s and 1980s, the Russian zoologists Geptner, Gromov and Baranova disagreed with this classification. They emphasized the differences of skins and skulls at their disposal and the ones originating in Southeast Asia, and coined the term Amur forest cat, which they regarded as a distinct species.[31][32] In 1987, Chinese zoologists pointed out the affinity of leopard cats from northern China, Amur cats and leopard cats from southern latitudes. In view of the morphological similarities they did not support classifying the Amur cat as a species.[33]

The initial binomial euptilura given by Elliott[29] was eventually changed to euptilurus referring to the ICZN Principle of Gender Agreement; at present, both terms are used.[34]

Molecular analysis of 39 leopard cat tissue samples clearly showed three clades: a northern lineage and southern lineages 1 and 2. The northern lineage comprises leopard cats from Tsushima Islands, the Korean Peninsula, the continental Far East, Taiwan, and Iriomote Island. Southern lineage 1, comprising Southeast Asian populations, showed higher genetic diversity. Southern lineage 2 is genetically distant from the other lineages.[17]

Leopard cats and hybrids as pets

Archeological and morphometric studies have indicated that the first cat species to become a human commensal or domesticate in Neolithic China was the leopard cat, beginning at least 5000 years ago. However, these cats were ultimately replaced over time with cats descended from Felis sylvestris lybica from the Middle East.[35]

The Asian leopard cat (P. b. bengalensis) has been mated with a domestic cat since the 1960s to produce hybrid offspring known as the Bengal cat. This hybrid is usually permitted to be kept as a pet without a license. For the typical pet owner, a Bengal cat should be at least four generations (F4) removed from the leopard cat. The "foundation cats" from the first three filial generations of breeding (F1–F3) are usually reserved for breeding purposes or the specialty-pet home environment.[36]

Keeping a leopard cat as a pet may require a license in some localities. License requirements vary.[37]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ross, J.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Hearn, A.; Izawa, M.; Loken, B.; Lynam, A.; McCarthy, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Phan, C.; Rasphone, A. & Wilting, A. (2015). "Prionailurus bengalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 542. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Groves, C. P. (1997). "Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 62: 330–338.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). Wild cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–232. ISBN 0-226-77999-8.

- 1 2 Chua, Marcus A. H.; Sivasothi, N.; Meier, R. (2016). "Population density, spatiotemporal use and diet of the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) in a human-modified succession forest landscape of Singapore" (PDF). Mammal Research. 61 (2): 99–108. doi:10.1007/s13364-015-0259-4. ISSN 2199-2401.

- ↑ Lorica, M. R. P.; Heaney, L. R. (2013). "Survival of a native mammalian carnivore, the leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 (Carnivora: Felidae), in an agricultural landscape on an oceanic Philippine island". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 5 (10): 4451–4460. doi:10.11609/JoTT.o3352.4451-60. ISSN 0974-7907.

- ↑ Ghimirey, Y., Ghimire, B. (2010). Leopard Cat at high altitude in Makalu-Barun National Park, Nepal. Cat News 52: 16–17.

- ↑ WCN (2012). Leopard Cat found at 4500m. Wildlife Conservation Nepal.

- ↑ Geptner, V. G., Sludskii, A. A. (1972). Mlekopitaiuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Vysšaia Škola, Moskva. (In Russian; English translation: Heptner, V.G., Sludskii, A.A., Komarov, A., Komorov, N.; Hoffmann, R.S. (1992). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol III: Carnivores (Feloidea). Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, Washington DC)

- ↑ Roberts, T.J. (1977). The mammals of Pakistan. Ernest Benn, London.

- ↑ Habibi, K. (2004). Mammals of Afghanistan. Zoo Outreach Organisation, Coimbatore, India.

- ↑ Rajaratnam, R. (2000). Ecology of the leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis in Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia. PhD Thesis, Universiti Kabangsaan Malaysia.

- 1 2 Grassman Jr, L. I., Tewes, M. E., Silvy, N. J., Kreetiyutanont, K. (2005). Spatial organization and diet of the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) in north-central Thailand. Journal of Zoology (London) 266: 45–54.

- ↑ Ohdachi, S.; Ishibashi, Y.; Iwasa, A.M.; Fukui, D., Saitohet, T.; et al. (2015). The Wild Mammals of Japan. Shoukadoh. ISBN 978-4-87974-691-7.

- ↑ Wilson, D. E., Mittermeier, R. A. (eds.) (2009). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 1: Carnivores. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ellerman, J. R., Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946. Second edition. British Museum of Natural History, London. Pp. 312–313

- 1 2 Tamada, T.; Siriaroonrat, B.; Subramaniam, V.; Hamachi, M.; Lin, L.-K.; Oshida, T.; Rerkamnuaychoke, W.; Masuda, R. (2006). "Molecular Diversity and Phylogeography of the Asian Leopard Cat, Felis bengalensis, Inferred from Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal DNA Sequences" (PDF). Zoological Science. 25: 154–163. doi:10.2108/zsj.25.154. PMID 18533746.

- ↑ Imaizumi, Y. (1967). A new genus and species of cat from Iriomote, Ryukyu Islands. Journal of Mammalian Society Japan 3(4): 74.

- ↑ Masuda, R.; Yoshida, M. C. (1995). "Two Japanese wildcats, the Tsushima cat and the Iriomote cat, show the same mitochondrial DNA lineage as the leopard cat Felis bengalensis". Zoological Science. 12: 655–659. doi:10.2108/zsj.12.655.

- ↑ Ministry of the Environment, Tsushima Wildlife Conservation Center (2005). National Endangered Species Tsushima Leopard Cat - English Version.

- 1 2 Murayama, A. (2008). The Tsushima Leopard Cat (Prionailurus bengalensis euptilura): Population Viability Analysis and Conservation Strategy. MSc thesis in Conservation Science. Imperial College London.

- 1 2 Rajaratnam, R., Sunquist, M., Rajaratnam, L., Ambu, L. (2007). Diet and habitat selection of the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis borneoensis) in an agricultural landscape in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Journal of Tropical Ecology 23: 209–217.

- ↑ Nowell, K., Jackson, P. (1996). Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis (Kerr 1792): Principal Threats in: Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland

- ↑ Shepherd, C. R., Nijman, V. (2008). The wild cat trade in Myanmar. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

- ↑ Department of the Interior. (1976). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. Endangered Status of 159 Taxa of Animals. Federal Register Vol. 41 (115): 24062−24067.

- ↑ Kerr, R; Gmelin, S.G. (1792). The animal kingdom or zoological system of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus : class I. Mammalia : containing a complete systematic description ... being a translation of that part of the Systema Naturae. London : Murray.

- ↑ Pocock, R.I. (1939). The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. Taylor and Francis, Ltd., London. Pp. 266–276

- ↑ Thomas, O. (1908). The Duke of Bedford's zoological exploration in Eastern Asia. – VII List of mammals from the Tsushima Islands. Proceedings of Zoological Society of London, 1908 (January – April): 47–54.

- 1 2 Elliott, D.G. (1871). Remarks on Various Species of Felidae, with a Description of a Species from North-Western Siberia. Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London for the Year 1871. Pp. 765–761.

- ↑ Mori, T. (1922). On some new Mammals from Korea and Manchuria. Felis manchurica, sp. n. Annals and magazine of natural history : including zoology, botany and geology. Vol. X, Ninth Series: 609–610

- ↑ Heptner, V. G. (1971). [On the systematic position of the Amur forest cat and some other east Asian cats placed in Felis bengalensis Kerr, 1792.] Zoologicheskii Zhurnal 50: 1720–1727 (in Russian)

- ↑ Gromov, I.M., Baranova, G.I., Baryšnikov, G. F. (eds.) (1981). Katalog mlekopitaûŝih SSSR : pliocen--sovremennostʹ Zoologičeskij Institut "Nauka." Leningradskoe otdelenie, Leningrad

- ↑ Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.L.; Ye, Z.Y.; Zhou, J.D.; eds. (1987). [Fauna Sinica. Mammalia 8: Carnivora.] Science Press, Beijing. (in Chinese)

- ↑ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. "What if the spelling is changed later?". Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ Vigne, J.-D.; Evin, A.; Cucchi, T.; Dai, L.; Yu, C.; Hu, S.; Soulages, N.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Gao, J.; Dobney, K.; Yuan, J. (2016-01-22). "Earliest "Domestic" Cats in China Identified as Leopard Cat (Prionailurus bengalensis)". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147295.

- ↑ The Bengal Cat Guide

- ↑ http://www.leopardcat.8k.com/purchasingLC.html

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Prionailurus bengalensis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prionailurus bengalensis. |

- Cat Specialist Group: Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis

- Leopard Cat Foundation

- BBC Wildlife Finder: The Leopard Cat