Prenatal perception

Prenatal perception is the study of the extent of somatosensory and other types of perception during pregnancy. In practical terms, this means the study of fetuses; none of the accepted indicators of perception are present in embryos.

Studies in the field inform the abortion debate, along with certain related pieces of legislation in countries affected by that debate.

Prenatal hearing

Numerous studies have found evidence indicating a fetus's ability to respond to auditory stimuli. Research at Zhejiang University, China indicates that fetuses of 33–41 weeks gestational age can not only hear, but also distinguish their mothers' voices from others.[1][2] See also a UK study on child's "Hearing and listening in the womb":[3] and UK material on "How babies develop hearing":[4]

Prenatal pain

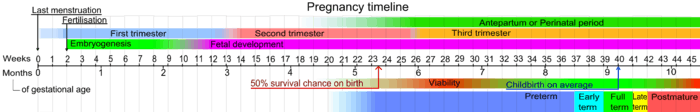

The hypothesis that human fetuses are capable of perceiving pain in the first trimester is not supported by science; the scientific consensus is that a fetus "is not capable of feeling pain until the third trimester",[5][6][7] which "begins at about 27 weeks of pregnancy".

In March 2010, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists submitted a report,[8] concluding that "Current research shows that the sensory structures are not developed or specialized enough to respond to pain in a fetus of less than 24 weeks", pg. 22.

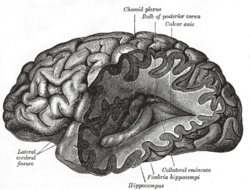

The neural regions and pathways that are responsible for pain experience remain under debate but it is generally accepted that pain from physical trauma requires an intact pathway from the periphery, through the spinal cord, into the thalamus and on to regions of the cerebral cortex including the primary sensory cortex (S1), the insular cortex and the anterior cingulated cortex.3,4 Fetal pain is not possible before these necessary neural pathways and structures (figure 1) have developed. -pg. 3

The report specifically identified the anterior cingulate as the area of the cerebral cortex responsible for pain processing. The anterior cingulate is part of the cerebral cortex, which begins to develop in the fetus at week 26.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco in the Journal of the American Medical Association concluded in a meta-analysis of data from dozens of medical reports and studies that fetuses are unlikely to feel pain until the third trimester of pregnancy.[6][9] There is a consensus among developmental neurobiologists that the establishment of thalamocortical connections (at weeks 22-34, reliably at 29) is a critical event with regard to fetal perception of pain, as they allow peripheral sensory information to arrive at the cortex.[10]

Electroencephalography indicates that the capacity for functional pain perception in premature infants does not exist before 29 or 30 weeks; a 2005 meta-analysis states that withdrawal reflexes and changes in heart rates and hormone levels in response to invasive procedures are reflexes that do not indicate fetal pain.[6]

Also in 2005, David Mellor and colleagues reviewed several lines of evidence that suggested a fetus does not awaken during its time in the womb. Mellor notes that much of the literature on fetal pain simply extrapolates from findings and research on premature babies. He questions the value of such data:

Systematic studies of fetal neurological function suggest, however, that there are major differences in the in utero environment and fetal neural state that make it likely that this assumption is substantially incorrect.

He and his team detected the presence of such chemicals as adenosine, pregnanolone, and prostaglandin-D2 in both human and animal fetuses, indicating that the fetus is both sedated and anesthetized when in the womb. These chemicals are oxidized with the newborn's first few breaths and washed out of the tissues, allowing consciousness to occur. If the fetus is asleep throughout gestation then the possibility of fetal pain is greatly minimized.[11] "A fetus," Mellor told The New York Times, "is not a baby who just hasn’t been born yet.".[12] Nonetheless, recent studies show that the neuromediators supposed to anesthetise the fetus in the womb can give just a slight sedation, as their levels in some cases overlap those in adults' blood.[13]

Fetal anesthesia

Direct fetal analgesia is used in only a minority of prenatal surgeries.[14]

Some caution that unnecessary use of fetal anesthetic may pose potential health risks to the mother. "In the context of abortion, fetal analgesia would be used solely for beneficence toward the fetus, assuming fetal pain exists. This interest must be considered in concert with maternal safety and fetal effectiveness of any proposed anesthetic or analgesic technique. For instance, general anesthesia increases abortion morbidity and mortality for women and substantially increases the cost of abortion. Although placental transfer of many opioids and sedative-hypnotics has been determined, the maternal dose required for fetal analgesia is unknown, as is the safety for women at such doses.[6]

Anesthesia researcher Laura Myers has suggested that fetal pain legislation may make abortions harder to obtain, because abortion clinics lack the equipment and expertise to supply fetal anesthesia. Currently, anesthesia is administered directly to fetuses only while they are undergoing surgery.[15]

Wendy Savage, press officer of Doctors for a Woman’s Choice on Abortion, pointed out that the majority of surgical abortions in Britain are already performed under general anesthesia, which also affects the fetus. In a letter to the British Medical Journal in April 1997, she deemed the discussion "unhelpful to women and to the scientific debate"[16] despite McCullagh and Saunders reporting in the British Medical Journal that "the theoretical possibility that the fetus may feel pain (albeit much earlier than most embryologists and physiologists consider likely) with the procedure of legal abortion".[17] Glover and Fisk have stated that "acute stress in fetuses… as shown by Doppler studies of human fetuses from 18 weeks undergoing invasive procedures" is evident.[18]

United States legislation

Federal legislation

In 2013 during the 113th Congress, Representative Trent Franks introduced a bill called the "Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act" (H.R. 1797). It passed in the House on June 18, 2013 and was received in the U.S. Senate, read twice, and referred to the Judiciary Committee.[19]

In 2004 during the 108th Congress, Senator Sam Brownback introduced a bill called the "Unborn Child Pain Awareness Act" for the stated purpose of "ensur[ing] that women seeking an abortion are fully informed regarding the pain experienced by their unborn child.", which was read twice and referred to committee.[20][21]

State legislation

Subsequently, 25 states have examined similar legislation related to fetal pain and/or fetal anesthesia,[15] and in 2010 Nebraska banned abortions after 20 weeks on the basis of fetal pain.[22] Eight states – Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Alaska, South Dakota, and Texas – have passed laws which introduced information on fetal pain in their state-issued abortion-counseling literature, which one opponent of these laws, the Guttmacher Institute founded by Planned Parenthood, has called "generally irrelevant" and not in line "with the current medical literature".[23] Dr. Arthur Caplan, director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania, said laws such as these "reduce... the process of informed consent to the reading of a fixed script created and mandated by politicians not doctors."[24]

See also

References

- ↑ Kisilevsky, B.S.; Hains, S.M.J.; Brown, C.A.; Lee, C.T.; Cowperthwaite, B.; Stutzman, S.S.; Swansburg, M.L.; Lee, K.; Xie, X.; Huang, H.; Ye, H.-H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Z. (2009). "Fetal sensitivity to properties of maternal speech and language". Infant Behavior and Development. 32 (1): 59–71. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.10.002. PMID 19058856.

- ↑ Smith, Laura S.; Dmochowski, Pawel A.; Muir, Darwin W.; Kisilevsky, Barbara S. (2007). "Estimated cardiac vagal tone predicts fetal responses to mother's and stranger's voices". Developmental Psychobiology. 49 (5): 543–7. doi:10.1002/dev.20229. PMID 17577240.

- ↑ http://www.maternal-and-early-years.org.uk/hearing-and-listening-in-the-womb[]

- ↑ http://www.amplifon.co.uk/resources/how-babies-develop-hearing/[]

- ↑ http://www.livescience.com/54774-fetal-pain-anesthesia.html 2016

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, Susan J.; Ralston, Henry J. Peter; Drey, Eleanor A.; Partridge, John Colin; Rosen, Mark A. (2005). "Fetal Pain". JAMA. 294 (8): 947–54. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.947. PMID 16118385.

- ↑ Derbyshire, S. W G (2006). "Can fetuses feel pain?". BMJ. 332 (7546): 909–12. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7546.909. PMC 1440624

. PMID 16613970.

. PMID 16613970. - ↑ Fetal Awareness – Review of Research and Recommendations for Practice:

- ↑ AP (August 24, 2005). "Study: Fetus feels no pain until third trimester". MSNBC.

- ↑ Johnson, Martin and Everitt, Barry. Essential reproduction (Blackwell 2000), p. 235. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ↑ Mellor, David J.; Diesch, Tamara J.; Gunn, Alistair J.; Bennet, Laura (2005). "The importance of 'awareness' for understanding fetal pain". Brain Research Reviews. 49 (3): 455–71. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.006. PMID 16269314.

- ↑ Paul, AM (2008-02-10). "The First Ache". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bellieni, Carlo Valerio; Buonocore, Giuseppe (2012). "Is fetal pain a real evidence?". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 25 (8): 1203. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.632040.

- ↑ Bellieni, Carlo V.; Tei, M.; Stazzoni, G.; Bertrando, S.; Cornacchione, S.; Buonocore, G. (2012). "Use of fetal analgesia during prenatal surgery". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 26: 90. doi:10.3109/14767058.2012.718392.

- 1 2 Paul, Annie Murphy (February 10, 2008). "The First Ache". New York Times.

- ↑ Savage, W.; Wall, P. D; Derbyshire, S. W. (1997). "Do fetuses feel pain?". BMJ. 314 (7088): 1201. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7088.1201.

- ↑ McCullagh, P.; Saunders, P J (1997). "Do fetuses feel pain?". BMJ. 314 (7076): 302. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7076.302a.

- ↑ Szawarski, Z (1996). "Do fetuses feel pain? Probably no pain in the absence of "self"". BMJ. 313 (7060): 796–7. PMC 2352169

. PMID 8842076.

. PMID 8842076. - ↑ Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act of 2013 H.R.1797, 113th Cong., 1st Sess. (2013)

- ↑ Unborn Child Pain Awareness Act of 2005, S.2466, 108t Cong., 2nd Sess. (2004)

- ↑ Weisman, Jonathan. "House to Consider Abortion Anesthesia Bill", Washington Post 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ↑ Kliff, Sarah Newly Passed 'Fetal Pain' Bill in Nebraska Is a Big Deal The Daily Beast Apr 13, 2010

- ↑ Gold Rachel Benson; Nash Elizabeth (2007). "State Abortion Counseling Policies and the Fundamental Principles of Informed Consent". Guttmacher Policy Review. 10 (4).

- ↑ Caplan, Arthur. "Abortion politics twist facts in fetal pain laws" MSNBC.com, November 30, 2005

External links

- "Oversight Hearing on Pain of the Unborn" from U.S. Congress, House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties (2005). This includes testimony both for and against proposed legislation dealing with fetal pain.

- "Can a embryo or fetus feel pain? Various opinions and studies" from Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. This site states: "We feel that all women considering an abortion should be fully informed and as free as possible from outside pressure."

- Pro-life site presenting case for fetal pain from second month of pregnancy: HTML version.

- Statement of National Abortion Federation Opposing H.R. 3442, the "Unborn Child Pain Awareness Act" (2008) PDF version and HTML version.

- National Right to Life Committee's webpage of testimonies regarding fetal pain: HTML version

- Small survivors: How the disputed science of fetal pain is reshaping abortion law by Eric Schulzke in Deseret News