Bokmål

| Norwegian Bokmål | |

|---|---|

| bokmål | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ˈbuːkmoːl] |

| Native to | Norway |

Native speakers |

None (written only) |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms |

Old East Norse

|

Standard forms |

Bokmål (official)

Riksmål (unofficial)

|

| Latin (Norwegian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Norway Nordic Council |

| Regulated by |

Norwegian Language Council (Bokmål proper) Norwegian Academy (Riksmål) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

nb |

| ISO 639-2 |

nob |

| ISO 639-3 |

nob |

| Glottolog |

(insufficiently attested or not a distinct language)norw1259[1] |

| Linguasphere |

52-AAA-ba to -be & |

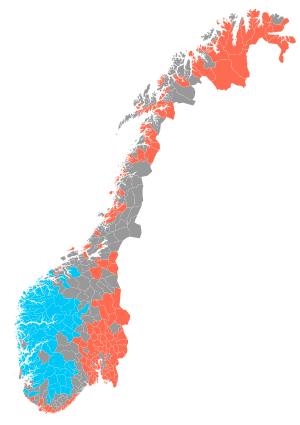

Bokmål ([ˈbuːkmoːl], literally "book tongue") is an official written standard for the Norwegian language, alongside Nynorsk. Bokmål is the preferred written standard of Norwegian for 85% to 90%[2] of the population in Norway, and is most used by people who speak Standard Østnorsk.

Bokmål is regulated by the governmental Norwegian Language Council. A more conservative orthographic standard, commonly known as Riksmål, is regulated by the non-governmental Norwegian Academy for Language and Literature. The written standard is a Norwegianised variety of the Danish language.

The first Bokmål orthography was officially adopted in 1907 under the name Riksmål after being under development since 1879.[3] The architects behind the reform were Marius Nygaard and Jacob Jonathan Aars.[4] It was an adaptation of written Danish, which was commonly used since the past union with Denmark, to the Dano-Norwegian koiné spoken by the Norwegian urban elite, especially in the capital. When the large conservative newspaper Aftenposten adopted the 1907 orthography in 1923, Danish writing was practically out of use in Norway. The name Bokmål was officially adopted in 1929 after a proposition to call the written language Dano-Norwegian lost by a single vote in the Lagting (a chamber in the Norwegian parliament).[3]

The government does not regulate spoken Bokmål and recommends that normalised pronunciation should follow the phonology of the speaker's local dialect.[5] Nevertheless, there is a spoken variety of Norwegian that is commonly seen as the de facto standard for spoken Bokmål. In The Phonology of Norwegian, Gjert Kristoffersen writes that

Bokmål [...] is in its most common variety looked upon as reflecting formal middle-class urban speech, especially that found in the eastern part of Southern Norway, with the capital Oslo as the obvious centre. One can therefore say that Bokmål has a spoken realisation that one might call an unofficial standard spoken Norwegian. It is in fact often referred to as Standard Østnorsk ('Standard East Norwegian').[6]

Standard Østnorsk (Standard East Norwegian) is the pronunciation most commonly given in dictionaries and taught to foreigners in Norwegian language classes.

History

Up until about 1300, the written language of Norway, Old Norwegian, was essentially the same as the other Old Norse dialects. The speech, however, was gradually differentiated into local and regional dialects. As long as Norway remained an independent kingdom, the written language remained essentially constant.[7]

In 1380, Norway entered into a personal union with Denmark. By the early 16th century, Norway had lost its separate political institutions, and together with Denmark formed the political unit known as Denmark–Norway until 1814, progressively becoming the weaker member of the union. During this period, the modern Danish and Norwegian languages emerged. Norwegian went through a Middle Norwegian transition, and a Danish written language more heavily influenced by Low German was gradually standardised. This process was aided by the Reformation, which prompted Christiern Pedersen's translation of the Bible into Danish. Remnants of written Old Norse and Norwegian were thus displaced by the Danish standard, which became used for virtually all administrative documents.[7][8]

Norwegians used Danish primarily in writing, but it gradually came to be spoken by urban elites on formal or official occasions. Although Danish never became the spoken language of the vast majority of the population, by the time Norway's ties with Denmark were severed in 1814, a Dano-Norwegian vernacular often called the "educated daily speech" had become the mother tongue of elites in most Norwegian cities, such as Bergen, Kristiania and Trondheim. This Dano-Norwegian koiné could be described as Danish with regional Norwegian pronunciation (see Norwegian dialects), some Norwegian vocabulary, and simplified grammar.[9]

With the gradual subsequent process of Norwegianisation of the written language used in the cities of Norway, from Danish to Riksmål to Bokmål, the upper-class sociolects in the cities changed accordingly. In 1814, when Norway was ceded from Denmark to Sweden, Norway defied Sweden and her allies, declared independence and adopted a democratic constitution. Although compelled to submit to a dynastic union with Sweden, this spark of independence continued to burn, influencing the evolution of language in Norway. Old language traditions were revived by the patriotic poet Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845), who championed an independent non-Danish written language.[8] Haugen indicates that:

"Within the first generation of liberty, two solutions emerged and won adherents, one based on the speech of the upper class and one on that of the common people. The former called for Norwegianisation of the Danish writing, the latter for a brand new start."[7]

The more conservative of the two language transitions was advanced by the work of writers like Peter Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, schoolmaster and agitator for language reform Knud Knudsen, and Knudsen's famous disciple, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, as well as a more cautious Norwegianisation by Henrik Ibsen.[7][10] In particular, Knudsen's work on language reform in the mid-19th century was important for the 1907 orthography and a subsequent reform in 1917, so much so that he is now often called the "father of Bokmål".

Controversy

Riksmål vs. Bokmål

The term Riksmål, meaning National Language, was first proposed by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson in 1899 as a name for the Norwegian variety of written Danish as well as spoken Dano-Norwegian. It was borrowed from Denmark where it denoted standard written and spoken Danish. The same year the Riksmål movement became organised under his leadership in order to fight against the growing influence of Nynorsk, eventually leading to the foundation of the non-governmental organisation Riksmålsforbundet in 1907. Bjørnson became Riksmålsforbundet's first leader until his death in 1910.

The 1917 reform introduced some elements from Norwegian dialects and Nynorsk as optional alternatives to traditional Dano-Norwegian forms. This was part of an official policy to bring the two Norwegian languages more closely together, intending eventually to merge them into one. These changes met resistance from the Riksmål movement, and Riksmålsvernet (The Society for the Protection of Riksmål) was founded in 1919.

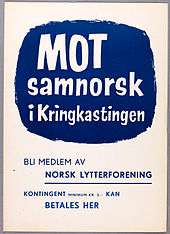

The 1938 reform in Bokmål introduced more elements from dialects and Nynorsk, and more importantly, many traditional Dano-Norwegian forms were excluded. This so-called radical Bokmål or Samnorsk (Common Norwegian) met even stiffer resistance from the Riksmål movement, culminating in the 1950s under the leadership of Arnulf Øverland. Riksmålsforbundet organised a parents' campaign against Samnorsk in 1951, and the Norwegian Academy for Language and Literature was founded in 1953. Because of this resistance, the 1959 reform was relatively modest, and the radical reforms were partially reverted in 1981 and 2005.

Currently, Riksmål denotes the moderate, chiefly pre-1938, unofficial variant of Bokmål, which is still in use and is regulated by the Norwegian Academy and promoted by Riksmålsforbundet. Riksmål has gone through some spelling reforms, but none as profound as the ones that shaped Bokmål. A Riksmål dictionary was published in four volumes in the period 1937 to 1957 by Riksmålsvernet, and two supplementary volumes were published in 1995 by the Norwegian Academy. After the latest Bokmål reforms, the difference between Bokmål and Riksmål have diminished and they are now comparable to American and British English differences, but the Norwegian Academy still upholds its own standard.

Norway's most popular daily newspaper, Aftenposten, is notable for its use of Riksmål as its standard language. Use of Riksmål is rigorously pursued, even with regard to readers' letters, which are "translated" into the standard.

Terminology

In the Norwegian discourse, the term Dano-Norwegian is seldom used with reference to contemporary Bokmål and its spoken varieties. The nationality of the language has been a hotly debated topic, and its users and proponents have generally not been fond of the implied association with Danish (hence the neutral names Riksmål and Bokmål, meaning state language and book language respectively). The debate intensified with the advent of Nynorsk in the 19th century, a written language based on rural Modern Norwegian dialects and puristic opposition to the Danish and Dano-Norwegian spoken in Norwegian cities.

Characteristics

Differences from Danish

The following table shows a few central differences between Bokmål and Danish.

| Danish | Bokmål | |

|---|---|---|

| Definite plural suffix either -ene or -erne the women the wagons |

yes kvinderne vognene |

no kvinnene vognene |

| West Scandinavian diphthongs heath hay |

no hede hø |

yes hei høy |

| Softening of p, t and k loss (noun) food (noun) roof (noun) |

yes tab mad tag |

no tap mat tak |

| Danish vocabulary afraid (adjective) angry (adjective) boy (noun) frog (noun) |

yes bange (also ræd) vred dreng (also gut) frø |

no redd sint gutt frosk |

Differences from the traditional Oslo dialect

Most natives of Oslo today speak a dialect that is an amalgamation of vikværsk (which is the technical term for the traditional dialects in the Oslofjord area) and written Danish; and subsequently Riksmål and Bokmål, which primarily inherited their non-Oslo elements from Danish. The present day Oslo dialect is also influenced by other Eastern Norwegian dialects.[6]

The following table shows some important cases where traditional Bokmål and Standard Østnorsk followed Danish rather than the traditional Oslo dialect as it is commonly portrayed in literature about Norwegian dialects.[6][11] In many of these cases, radical Bokmål follows the traditional Oslo dialect and Nynorsk, and these forms are also given.

| Danish | Bokmål/Standard Østnorsk | traditional Oslo dialect | Nynorsk1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| traditional | radical | ||||

| Differentiation between masculine and feminine a small man a small woman |

no en lille mand en lille kvinde |

no en liten mann en liten kvinne |

yes en liten mann ei lita kvinne |

yes en liten mann ei lita kvinne |

yes ein liten mann ei lita kvinne |

| Differentiation between masc. and fem. definite plural the boats the wagons |

no bådene vognene |

no båtene vognene |

yes båta vognene |

yes båtane vognene | |

| Definite plural neuter suffix the houses |

-ene/erne husene |

-ene husene |

-a husa |

-a husa |

-a husa |

| Weak past participle suffix cycled |

-et cyklet |

-et syklet |

-a sykla |

-a sykla |

-a sykla |

| Weak preterite suffix cycled |

-ede cyklede |

-et syklet |

-a sykla |

-a sykla |

-a sykla |

| Strong past participle suffix written |

-et skrevet |

-et skrevet |

-i skrivi |

-e skrive | |

| Split infinitive come lie (in bed) |

no komme ligge |

no komme ligge |

yes komma ligge |

yes koma ligge | |

| Splitting of masculines ending on unstressed vowel ladder round |

no stige runde |

no stige runde |

yes stega runde |

no stige runde | |

| West Scandinavian diphthongs leg (noun) smoke (noun) soft/wet (adjective) |

no ben røg blød |

no ben røk bløt |

yes bein røyk blaut |

yes bein røyk blaut |

yes bein røyk blaut |

| West Scandinavian u for o bridge (noun) |

no bro |

no bro2 |

yes bru |

yes bru |

yes bru |

| West Scandinavian a-umlaut floor (noun) |

no gulv |

no gulv |

yes golv |

yes gølv |

yes golv |

| Stress on first syllable in loan words banana (noun) |

no /ba'naːn/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation |

yes /'banan/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation | |

| Retroflex flap /ɽ/ from old Norse /rð/ table, board (noun) |

no /boːr/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation |

yes /buːɽ/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation | |

| Retroflex flap /ɽ/ from old Norse /l/ sun (noun) |

no /soːl/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation |

yes /suːɽ/ |

no officially recognised standard pronunciation | |

1 Closest match to the traditional Oslo dialect.

2 However, Bokmål uses ku "cow" and (now archaic) su "sow" exclusively.

See also

| Bokmål language edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Danish language

- Differences between Norwegian Bokmål and Standard Danish

- History of Norway

- Norwegian language

- Norwegian language conflict

- Nynorsk

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Norwegian Bokmål". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Vikør, Lars. "Fakta om norsk språk". Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- 1 2 Lundeby, Einar. "Stortinget og språksaken". Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Halvorsen, Eyvind Fjeld. "Marius Nygaard". In Helle, Knut. Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ "Råd om uttale". Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- 1 2 3 Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000). The Phonology of Norwegian. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Haugen, Einar (1977). Norwegian English Dictionary. Oslo: Unifersitetsforlaget. ISBN 0-299-03874-2.

- 1 2 Gjerset, Knut (1915). History of the Norwegian People, Volumes I & II. The MacMillan Company. ISBN none.

- ↑ Hoel, Oddmund Løkensgard (1996). Nasjonalisme i norsk målstrid 1848–1865. Oslo: Noregs Forskingsråd. ISBN 82-12-00695-6.

- ↑ Larson, Karen (1948). A History of Norway. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Skjekkeland, Martin (1997). Dei norske dialektane. Høyskoleforlaget. ISBN 82-7634-103-9.