Ole Miss riot of 1962

| Ole Miss riot of 1962 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

|

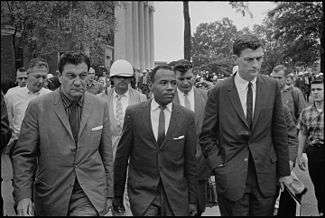

Chief U.S. Marshal James McShane (left) and Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, John Doar (right) of the Justice Department, escorting James Meredith to class at Ole Miss. | |||

| Date | September 30, 1962 – October 1, 1962 (2 days) | ||

| Location | Lyceum-The Circle Historic District, University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi | ||

| Causes |

| ||

| Result |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

The Ole Miss riot of 1962, or Battle of Oxford, was fought between Southern segregationist civilians and federal and state forces beginning the night of September 30, 1962; segregationists were protesting the enrollment of James Meredith, a black US military veteran, at the University of Mississippi (known affectionately as Ole Miss) at Oxford, Mississippi. Two civilians were killed during the night, including a French journalist, and over 300 people were injured,[1] including one third of the US Marshals deployed.

Background

In 1954 the US Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Meredith applied as a legitimate student with strong experience as an Air Force veteran and good grades in completed coursework at Jackson State University. Despite this, his entrance was barred first by university officials, and later by segregationist Governor Ross Barnett.

In late September, 1962, the administration of President John F. Kennedy had extensive discussions with Governor Barnett and his staff about protecting Meredith, but Barnett publicly vowed to keep the university segregated. The President and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy wanted to avoid bringing in federal forces for several reasons. Robert Kennedy hoped that legal means, along with the escort of U.S. Marshals, would be enough to force the Governor to comply.[2] He also was very concerned there might be a "mini-civil war" between the U.S. Army troops and armed protesters.[2]

Governor Barnett, under pressure from the courts, conducted secret back door discussions in response to calls from the Kennedy administration between Thursday September 27 and Sunday the 30th.[3] He was committed to maintain civil order and reluctantly agreed to allow Meredith to register in exchange for a scripted face-saving event. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy ordered 500 U.S. Marshals to accompany Meredith during his arrival and registration.

Events

In accordance with Barnett and Kennedy's plan, on Sunday evening, September 30, the day before the anticipated showdown, Meredith was flown to Oxford. He was quietly escorted by Mississippi Highway Patrol as he moved into a dorm room. The federal marshals assembled on to campus, supported by the 70th Army Engineer Combat Battalion from Ft Campbell, Kentucky. Responding to the federal presence, a crowd of a thousand, mostly students quickly crowded onto campus. As the scene grew more out of control, at first the highway patrol helped hold off the crowds, but, despite Barnett's renewed commitment, they were withdrawn by State Senator George Yarbrough starting at about 7:25 pm local time.[4][5] The students, increasingly joined by other agitators, started to break out into a full riot on the Oxford campus.

The crowd eventually swelled to about three thousand. As its behavior turned increasingly violent, including the death of a journalist, the marshals ran out of tear gas defending the officials in the Lyceum. President Kennedy reluctantly decided to call in reinforcements in the middle of the night under the command of Brigadier General Charles Billingslea. He ordered in U.S. Army military police from the 503rd and 716th Military Police Battalions, which had previously been readied for deployment under cover of the nuclear war Exercise Spade Fork, plus the U.S. Border Patrol and the federalized Mississippi National Guard. U.S. Navy medical personnel (physicians and hospital corpsmen) attached to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Millington, Tennessee, were also sent to the university.

Before they arrived, rioters roaming the campus discovered Meredith was in Baxter Hall and started to assault it. Early in the morning, as Gen. Billingslea's party entered the university gate, a white mob attacked his staff car and set it on fire. Billingslea, the Deputy Commanding General John Corley, and aide, Capt Harold Lyon, were trapped inside the burning car, but they forced the door open, then crawled 200 yards under gunfire from the mob to the University Lyceum Building. The army did not return this fire. To keep control, Gen Billingslea had established a series of escalating secret code words for issuing ammunition down to the platoons, a second one for issuing it to squads, and a third one for loading, none of which could take place without the General confirming the secret codes.

By the end, one third of the US Marshals, a total of 166 men, were injured in the melee, and 40 soldiers and National Guardsmen were wounded.[6]

Two men were murdered during the first night of the riots: French journalist Paul Guihard,[7] on assignment for the London Daily Sketch, who was found behind the Lyceum building with a gunshot wound to the back; and 23-year-old Ray Gunter, a white jukebox repairman who had visited the campus out of curiosity. Gunter was found with a bullet wound in his forehead. Law enforcement officials described these as execution-style killings.[8]

Finally, on October 1, 1962, Meredith became the first African-American student to be enrolled at the University of Mississippi,[9] and attended his first class, in American History.[1] Meredith graduated from the university on August 18, 1963 with a degree in political science.[10] At that time, there were still hundreds of troops guarding him 24 hours a day.[11]

Governor Barnett was fined $10,000 and sentenced to jail for contempt. The charges were later dismissed by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Representation in other media

Sports journalist Wright Thompson wrote an article "Ghosts of Mississippi" (2010),[12] that described the riot and the football team's season that year. It was adapted as a documentary film for the ESPN 30 for 30 series, entitled The Ghosts of Ole Miss (2012), about the 1962 football team's perfect season and the early violence in the fall over integration of the historic university.[13]

Legacy

The event is regarded as a pivotal moment in the history of civil rights in the United States. Bob Dylan wrote and sang about the events in his song "Oxford Town". Charles W. Eagle described Meredith's achievement by the following:

"In a major victory against white supremacy, he had inflicted a devastating blow to white massive resistance to the civil rights movement and had goaded the national government into using its overpowering force in support of the black freedom struggle."[14]

- Because of the civil rights significance of Meredith's admission, the Lyceum-The Circle Historic District where the riot took place has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and state historic district.

- A statue of Meredith has been erected on the campus to commemorate his historic role.

- The university conducted a series of programs for a year beginning in 2002 to mark the 40th anniversary of its integration. In 2012, it initiated a yearlong series of programs to mark its 50th anniversary of integration.

References

- 1 2 "Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot". NPR. 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- 1 2 Schlesinger 2002, pp. 317-320.

- ↑ Branch 1988, p. 650.

- ↑ Branch 1988, p. 662.

- ↑ Bryant 2006, 71.

- ↑ Farber, David and Beth Bailey. The Columbia Guide to America in the 1960s.

- ↑ "Though the Heavens Fall (5 of 7)". TIME. October 12, 1962. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Bryant (2006), 70-71.

- ↑ "1962: Mississippi race riots over first black student". BBC News - On this day. October 1, 1962. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ↑ Leslie M. Alexander; Walter C. Rucker (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 890.

- ↑ Gallagher 2012, p. 187.

- ↑ Thompson, Wright (February 2010). "Ghosts of Mississippi". Outside the Lines. ESPN. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ↑ Thompson, Wright (October 30, 2012). "'Ghosts' a story of family, home". ESPN Films. ESPN.com. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ↑ Eagles, Charles W. (Spring 2009). "'The Fight for Men's Minds': The Aftermath of the Ole Miss Riot of 1962" (PDF). The Journal of Mississippi History. 71 (1): 1–53., reprinted at Mississippi Department of Archives and History website, accessed 1 August 2014

Bibliography

- Branch, Taylor (1988). Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-68742-7.

- Bryant, Nick (Autumn 2006). "Black Man Who Was Crazy Enough to Apply to Ole Miss". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (53): 60–71. (restricted access - subscription)

- Eagles, Charles W. (Spring 2009). "'The Fight for Men's Minds': The Aftermath of the Ole Miss Riot of 1962" (PDF). The Journal of Mississippi History. 71 (1): 1–53., reprinted at Mississippi Department of Archives and History website

- Gallagher, Henry (2012). James Meredith and the Ole Miss riot : A Soldier's story. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-61703-653-8.

- Schlesinger, Arthur (2002) [1978]. Robert Kennedy and His Times. New York: First Mariner Books. ISBN 0-618-21928-5.

Further reading

- Eagles, Charles W. (2009). The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807895597.

- Scheips, Paul J. (2005). "The Riot at Oxford". The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1945–1992 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. pp. 101–136. ISBN 9780160723612.