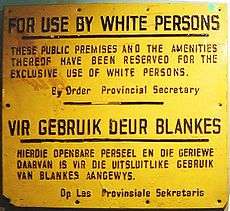

Separate but equal

| Part of a series of articles on Racial segregation | |

|---|---|

| |

| South Africa | |

| United States | |

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law according to which racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted in 1868, which guaranteed equal protection under the law to all citizens. Under the doctrine, as long as the facilities provided to each race were equal, state and local governments could require that services, facilities, public accommodations, housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation be segregated by race, which was already the case throughout the former Confederacy. The phrase was derived from a Louisiana law of 1890, although the law actually used the phrase "equal but separate."[1]

The doctrine was confirmed in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision of 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation. Though segregation laws existed before that case, the decision emboldened segregation states during the Jim Crow era, which had commenced in 1876 and supplanted the Black Codes, which restricted the civil rights and civil liberties of African Americans during the Reconstruction Era. 17 states had segregation laws.

In practice the separate facilities provided to African Americans were rarely equal; usually they were not even close to equal, or they did not exist at all. The doctrine was overturned by a series of Supreme Court decisions, starting with Brown v. Board of Education of 1954. However, the overturning of segregation laws in the United States was a long process that lasted through much of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, involving federal legislation (especially the Civil Rights Act of 1964), and many court cases.

Origins

The American Civil War (1861–1865), though technically focused on whether (pro-slavery) Southern states could secede from the Union, brought slavery in the United States to an end, with the Emancipation Proclamation during the war, and the Thirteenth Amendment shortly after.[2] Following the war, the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteed equal protection under the law to all citizens, and Congress established the Freedmen's Bureau to assist the integration of former slaves into Southern society. After the end of Reconstruction with the Compromise of 1877, and the withdrawal of federal troops from all Southern states, former slave-holding states enacted various laws to undermine the equal treatment of African Americans, although the Fourteenth Amendment as well as federal Civil Rights laws enacted during reconstruction were meant to guarantee it. However Southern states contended that the requirement of equality could be met in a manner that kept the races separate. Furthermore, the state and federal courts tended to reject the pleas by African Americans that their Fourteenth Amendment rights were violated, arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to federal, not state, citizenship. This rejection is evident in the Slaughter-House Cases and Civil Rights Cases.

After the end of Reconstruction, the federal government adopted a general policy of leaving racial segregation up to the individual states. One example of this policy was the second Morrill Act (Morrill Act of 1890). Before the end of the war, the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act (Morrill Act of 1862) had provided federal funding for higher education by each state with the details left to the state legislatures.[3] The 1890 Act which implicitly accepted the legal concept of separate but equal for the 17 states which had institutionalized segregation.

Provided, That no money shall be paid out under this act to any State or Territory for the support and maintenance of a college where a distinction of race or color is made in the admission of students, but the establishment and maintenance of such colleges separately for white and colored students shall be held to be a compliance with the provisions of this act if the funds received in such State or Territory be equitably divided as hereinafter set forth.[4][5]

Prior to the Second Morrill Act, 17 states excluded blacks from access to the land grant colleges without providing similar educational opportunities. In response to the Second Morrill Act, 17 states established separate land grant colleges for blacks which are now referred to as public historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). In fact, some states adopted laws prohibiting schools from educating blacks and whites together, even if a school was willing to do so. (The Constitutionality of such laws was upheld in Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908).) Under the 'separate but equal doctrine', blacks were entitled to receive the same public services and accommodations such as schools, bathrooms, and water fountains, but states were allowed to maintain different facilities for the two groups. The legitimacy of such laws under the 14th Amendment was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. The Plessy doctrine was extended to the public schools in Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528 (1899).

Although the Constitutional doctrine required equality, the facilities and social services offered to African-Americans were almost always of lower quality than those offered to white Americans; for example, many African American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools. In Texas, the state established a state-funded law school for white students without any law school for black students.

In 1892, Homer Plessy, who was of mixed ancestry and appeared to be white, boarded an all-white railroad car between New Orleans and Covington, Louisiana. The conductor of the train collected passenger tickets at their seats. When Plessy told the conductor he was 7/8ths white and 1/8th black, he was advised he needed to move to a coloreds-only car. Plessy said he resented sitting in a coloreds-only car and was arrested immediately.

One month after his arrest, Plessy appeared in court before Judge John Howard Ferguson. Plessy's lawyer, Albion Tourgee, claimed Plessy’s 13th and 14th amendment rights were violated. The 13th amendment abolished slavery, and the 14th amendment granted equal protection to all under the law.

The Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson established the phrase "separate but equal". The ruling "[required] railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches in that State to provide equal, but separate, accommodations for the white and colored races…".[6] Accommodations provided on each railroad car were required to be the same as those provided on the others. Separate railroad cars could be provided. The railroad could refuse service to passengers who refused to comply, and the Supreme Court ruled this did not infringe upon the 13th and 14th amendments.

The "separate but equal" doctrine applied to railroad cars and to schools, voting rights, and drinking fountains. Segregated schools were created for students, as long as they followed "separate but equal". The majority of all black schools received old textbooks, used equipment, and poorly prepared or trained teachers.[7] A study conducted by the American Psychological Association found that black students were emotionally impaired when segregated at a young age.[8] Furthermore, many black students were forced to associate with "white dolls" or colors similar, but lighter, than their own skin.[8] State voting right restrictions, such as literacy tests and poll taxes created an environment that made it almost impossible for blacks to vote. This era also saw separate drinking fountains in public areas.

The "Separate but Equal" doctrine was eventually overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. But African Americans were still not equal; poorer services and restrictions on voting rights still limited them throughout the United States, and they still were not granted more political and social power than before.

Rejection

The repeal of such restrictive laws, generally known as Jim Crow laws, was a key focus of the Civil Rights Movement prior to 1954. In Sweatt v. Painter, the Supreme Court addressed a legal challenge to the doctrine by a student seeking admission to a state-supported law school in Texas. Because Texas did not have a law school for blacks, the lower court delayed the case until Texas could create one. However, the Supreme Court ordered that the student be admitted to the white law school on the grounds that the separate school failed to qualify as being "equal," both because of quantitative differences in facilities and intangible factors, such as its isolation from most of the future lawyers with whom its graduates would interact. The court held that, when considering graduate education, intangibles must be considered as part of "substantive equality." The same day, the Supreme Court in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents ruled that Oklahoma segregation laws which required a graduate student working on a Doctor of Education degree to sit in the hallway outside the classroom door did not qualify as 'separate but equal.' These cases ended 'separate but equal' in graduate and professional education.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), attorneys for the NAACP referred to the phrase "equal but separate" used in Plessy v. Ferguson as a custom de jure racial segregation enacted into law. The NAACP, led by the soon-to-be first black Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, was successful in challenging the constitutional viability of the separate but equal doctrine, and the court voted to overturn sixty years of law that had developed under Plessy. The Supreme Court outlawed segregated public education facilities for blacks and whites at the state level. The companion case of Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 outlawed such practices at the Federal level in the District of Columbia. The court held:

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Even though the constitutionality of separate but equal in education had been overturned, it would be almost ten more years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would extinguish the application of separate but equal in all areas of public accommodations such as transportation and hotels. Additionally, in 1967 under Loving v. Virginia, the United States Supreme Court declared Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924", unconstitutional, and invalidated all anti-miscegenation laws in the United States. Although federal legislation prohibits racial discrimination in college admissions, the historically black colleges and universities continue to teach student bodies that are 75% to 90% African American.[9] This however does not necessarily indicate racial discrimination within college admissions in those schools when factors such as student preference are taken into account. In 1975, Jake Ayers Sr. filed a lawsuit against Mississippi, stating that they gave more financial support to the predominantly white public colleges. The state settled the lawsuit in 2002, directing $503 million to three historically black colleges over 17 years.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Separate but equal: West's Encyclopedia of American Law (Full Article) from Answers.com

- ↑ Williams G. Thomas (June 24, 2008). "How Slavery Ended in the Civil War". University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- ↑ Library of Congress. "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". loc.gov.

- ↑ "Act of August 30, 1890, ch. 841, 26 Stat. 417, 7 U.S.C. 322 et seq." Act of 1890 Providing for the Further Endowment and Support Of Colleges of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts.

- ↑ "104th Congress 1st Session, H. R. 2730" To eliminate segregationist monkey from the Second Morrill Act.

- ↑ Plessy v. Ferguson.

- ↑ "Black-white student achievement gap persists". NBC News. July 14, 2009.

- 1 2 Clark, Kenneth. "Segregation Ruled Unequal, Therefore Unconstitutional".

- ↑ "Historically Black Colleges and Universities,1976 to 2001" (PDF). Dept. of Education. September 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ "Opposition strong to Barbour's plan to merge Mississippi's 3 black universities into 1". Associated Press. November 19, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

Further reading

- Roche, John P. (1951). "The Future of "Separate but Equal"". Phylon. 12 (3): 219–226. doi:10.2307/271632.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Racial segregation in the United States. |

- A film clip A Study of Educational Inequalities in South Carolina is available at the Internet Archive

- Cornell Legal Information Institute