Operation Fortitude

| Operation Fortitude | |

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Bodyguard | |

Fortitude North and South constituted the main portion of the overall Bodyguard deception | |

| Operational scope | Military deception |

| Location | United Kingdom |

| Planned | December 1943 – March 1944 |

| Planned by | London Controlling Section, Ops (B), R Force |

| Target | Axis powers |

| Date | March – June 1944 |

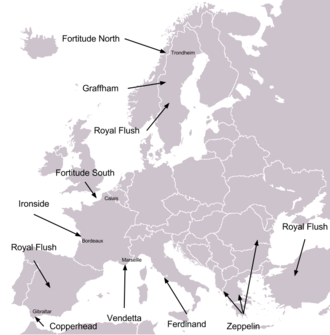

Operation Fortitude was the code name for a World War II military deception employed by the Allied nations as part of an overall deception strategy (code named Bodyguard) during the build-up to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was divided into two sub-plans, North and South, with the aim of misleading the German high command as to the location of the imminent invasion.

Both Fortitude plans involved the creation of phantom field armies (based in Edinburgh and the south of England) which threatened Norway (Fortitude North) and Pas de Calais (Fortitude South). The operation was intended to divert Axis attention away from Normandy and, after the invasion on June 6, 1944, to delay reinforcement by convincing the Germans that the landings were purely a diversionary attack.

Background

Fortitude was one of the major elements of Operation Bodyguard, the overall Allied deception stratagem for the Normandy landings. Bodyguard's principal objective was to ensure the Germans would not increase troop presence in Normandy by promoting the appearance that the Allied forces would attack in other locations. After the invasion (on June 6, 1944) the plan was to delay movement of German reserves to the Normandy beachhead and prevent a potentially disastrous counter-attack. Fortitude's objectives were to promote alternative targets of Norway and Calais.[1][2]

The planning of Operation Fortitude came under the auspices of the London Controlling Section (LCS), a secret body set up to manage Allied deception strategy during the war. However, the execution of each plan fell to the various theatre commanders, in the case of Fortitude this was Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) under General Dwight D. Eisenhower. A special section, Ops (B), was established at SHAEF to handle the operation (and all of the theatre's deception warfare). The LCS retained responsibility for what was called "Special Means"; the use of diplomatic channels and double-agents.[2]

Fortitude was split into two parts, North and South, both with similar aims. Fortitude North was intended to convince the German high command that the Allies, staging out of Scotland, would attempt an invasion of occupied Norway. Fortitude South employed the same tactic, with the apparent objective being Pas de Calais.[1]

Planning

Fortitude planning was ostensibly the responsibility of Noel Wild and his Ops (B) staff. However, in practice the work was shared between Wild and the heads of the LCS and B1a. Work began in December 1943, at first under the codename Mespot. Prime Minister Winston Churchill judged this unsuitable and so the Fortitude name was adopted on February 18.[note 1][3]

Fortitude South

Wild's first version of the Fortitude South plan was produced in early January 1943 and aimed to counter the likelihood that the Germans would notice invasion preparations in the South of England.[4] The intention was to create the impression that an invasion was aimed at the Pas de Calais some time in mid-July; once the real invasion had landed, six fictional divisions would keep this threat to Calais alive.[5] The Fortitude South plan would be implemented, at an operational level, by the invasion force—the 21st Army Group under the command of General Bernard Montgomery.[3]

This presented a problem, in the form of Colonel David Strangeways, head of Montgomery's R Force deception staff.[3] Strangeways had, in the opinion of Ops(B)'s Christopher Harmer, the same arrogance as his commanding officer. More important, he held a low opinion of the London establishment of the "old boys" clubs of Ops (B) and LCS. Dissatisfied with the Fortitude South outline he, in the words of Harmer, set out to ride "roughshod over the established deception organization".[5] Strangeways' criticisms highlighted that the plan aimed to cover the Allies real intentions, rather than create a realistic threat to Calais.[5][6] This was not the only issue, and Strangeways was not the only one to notice them. If the Germans were able to judge the Allied state of readiness in southwest England then they would be expecting an invasion in early June , which left several weeks to defeat any bridgehead and turn to the defence of Calais.[6]

On January 25, Montgomery's Chief of Staff Francis de Guingand sent a letter to the deception planners asking them, amongst other things, to focus on Pas de Calais as the main assault. It was almost certainly sent at the behest of Strangeways.[7] With these criticisms in hand, Wild produced his final draft for Fortitude South. In this revised plan, issued on January 30 and approved by the Allied chiefs on 18 February, fifty divisions would be positioned in Southern England to attack Pas de Calais.[5][7] After the real invasion had landed the story would change, suggesting to the Germans that several assault divisions remained in England ready to conduct a cross-channel attack once the Normandy beachhead had drawn German defences away from Calais. The plan still retained some of its earlier form, most notably that the first part of the story still aimed to suggest an invasion date of mid-July.[8] Strangeways was still unimpressed. He pointed out that convincing the Germans of so many fictional divisions would be tough, and even harder would be convincing them of Montgomery's ability to manage two entire invasions at the same time.[9] Wild's plan outlined ten divisions for the Calais assault, six of them fictional and the remainder being the real American V Corps and British I Corps. However, these corps would be part of the actual Normandy invasion and so it would be difficult to imply Calais being the main assault following D-Day.[10] Strangeways' final concerns related to the effort required for physical deception, as the plan called for large numbers of troop movements and dummy craft.[9]

I rewrote it entirely. It was too complicated, and the people who made it had not never done it before. Now they did their best - but it didn't suit the operation that Monty was considering ... You see so much depended on the success of that deception plan.

Strangeways, writing in 1996[11]

Strangeways' objections were so strong that he refused to undertake most of the physical deception. A power struggle ensued, throughout February and early March, between Ops(B) and Strangeways as to who had authority to implement each part of the deception plan. Montgomery put his full support behind his head of deception, and so Strangeways prevailed.[12][13] Finally, in a 23 February meeting between R Force and Ops(B), Strangeways tore up a copy of the plan, decreeing it useless, and announced that he would rewrite it from scratch.[9]

The established deceivers were dubious about Strangeways' announcement, assuming he would re-submit the existing plan with some modifications.[13] However, he duly submitted a re-written operation which was met, in Harmers words, with "astonishment".[11]

Strangeways' revised Fortitude South invented an entire new field army. The First United States Army Group (FUSAG) was a skeleton formation formed for administrative purposes, but never used. However, the Germans had discovered its existence through radio intercepts. Strangeways proposed activating the unit, with a series of fictional and real formations, to overcome the problem of Montgomery handling two invasions.[13] Moreover, he proposed that FUSAG should represent the main Allied threat to the Germans, which they would expect to land around Calais. Once Operation Neptune landings had taken place, this should be passed off as a diversion to distract German defences from the main attack by FUSAG.[14]

The new Fortitude South came with six subsidiary plans, Quicksilver I-VI, with specific implementation details.[14]

Special means

For deceptions the Allies had developed a number of methodologies, referred to as "special means". They included combinations of physical deception, fake wireless activity, leaks through diplomatic channels, and double agents. Fortitude used all of these techniques to various extents. For example, Fortitude North relied heavily on wireless transmission (the Allies thought that Scotland was too far for German reconnaissance to reach) while Fortitude South utilised the Allies network of double agents.

- Physical deception: to mislead the enemy with nonexistent units through fake infrastructure and equipment, such as dummy landing craft, dummy airfields, and decoy lighting.

- Controlled leaks of information through diplomatic channels, which might be passed on via neutral countries to the Germans.

- Wireless traffic: To mislead the enemy, wireless traffic was created to simulate actual units.

- Use of German agents controlled by the Allies through the Double Cross System to send false information to the German intelligence services.

- Public presence of notable staff associated with phantom groups such as FUSAG, most notably the well-known US general George S. Patton.

Double agents

One of the main deception channels for the Allies were double agents. B1A (the Counter-Intelligence Division of MI5) had done a good job intercepting all of the German agents in Britain. Many of these were recruited as double agents under the Double Cross System. The three most important double agents during the Fortitude operation were:

- Juan Pujol García (Garbo), a Catalan who managed to get recruited by German intelligence, and sent them abundant but convincing disinformation from Lisbon, until the Allies accepted his offer and he was employed by the British. He created a network of 27 imaginary sub-agents by the time of Fortitude, and the Germans unwittingly paid the British Exchequer large amounts of money regularly, thinking they were funding a network loyal to themselves. He was awarded both the Iron Cross by the Germans and an MBE by the British after D-Day.

- Roman Czerniawski (Brutus), a Polish officer who ran an intelligence network for the Allies in occupied France. Captured by the Germans, he was offered a chance to work for them as a spy. On his arrival in Britain, he subsequently turned himself in to British intelligence.

- Dusan Popov (Tricycle), a Yugoslav lawyer.

Fortitude North

Fortitude North was designed to mislead the Germans into expecting an invasion of Norway. By threatening any weakened Norwegian defence the Allies hoped to prevent or delay reinforcement of France following the Normandy invasion. The plan involved simulating a buildup of forces in northern England and political contact with Sweden.[15]

During a similar operation in 1943, Operation Cockade, a fictional field army (British Fourth Army) had been created, headquartered in Edinburgh Castle.[16] It was decided to continue to use the same force during Fortitude. Unlike its Southern counterpart the deception relied primarily on "Special Means" and fake radio traffic, since it was judged unlikely that German reconnaissance planes could reach Scotland unintercepted.[15][17] False information about the arrival of troops in the area were reported by double agents Mutt and Jeff, who had surrendered following their 1941 landing in the Moray Firth, while the British media cooperated by broadcasting fake information, such as football scores or wedding announcements, to nonexistent troops.[17]:464–466 Fortitude North was so successful that by late spring 1944, Hitler had thirteen army divisions in Norway.[18]

In the early spring of 1944, British commandos attacked targets in Norway to simulate preparations for invasion. They destroyed industrial targets, such as shipping and power infrastructure, as well as military outposts. This coincided with an increase in naval activity in the northern seas, and political pressure on neutral Sweden.[17]:466–467

Operation Skye

Operation Skye was the code name for the radio deception component of Fortitude North, involving simulated radio traffic between fictional army units. The programme began on 22 March 1944, overseen by Colonel R. M. McLeod, and became fully operational by 6 April.[17] The operation was split into four sections, relating to different divisions of the Fourth Army:

- Skye I; Fourth Army headquarters

- Skye II; British II Corps

- Skye III; American XV Corps (a genuine formation, but with fictional units added to its order of battle)

- Skye IV; British VII Corps.

In his 2000 book, Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign, Roger Fleetwood-Hesketh, who was a member of Ops (B), concluded that "No evidence has so far been found to show that wireless deception or visual misdirection made any contribution to Fortitude North". It is thought that the Germans were not in fact monitoring the radio traffic being simulated.[19]

Fortitude South

Fortitude South employed similar deception in the south of England, threatening an invasion at Pas de Calais by the fictional 1st U.S. Army Group (FUSAG). France was the crux of the Bodyguard plan; as the most logical choice for an invasion, the Allied high command had to mislead the German defences in a very small geographical area. The Pas de Calais offered a number of advantages over the chosen invasion site, such as the shortest crossing of the English Channel and the quickest route into Germany. As a result, German command, particularly Rommel, took steps to heavily fortify that area of coastline. The Allies decided to amplify this belief of a Calais landing.[20]

Montgomery, commanding the Allied landing forces, knew that the crucial aspect of any invasion was the ability to enlarge a beachhead into a full front. He also had only limited divisions at his command, 37 compared to around 60 German formations. Fortitude South's main aims were to give the impression of a much larger invasion force (the FUSAG) in the South-East of England, to achieve tactical surprise in the Normandy landings and, once the invasion had occurred, to mislead the Germans into thinking it a diversionary tactic with Calais the real objective.[20]

Operation Quicksilver

The key element of Fortitude South was Operation Quicksilver. It entailed the creation of the belief in German minds that the Allied force consisted of two army groups, 21st Army Group under Montgomery (the genuine Normandy invasion force), and 1st U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) (a fictitious force under General George Patton), positioned in south eastern England for a crossing at the Pas de Calais.

At no point were the Germans fed false documents describing the invasion plans. Instead they were allowed to construct a misleading order of battle for the Allied forces. To mount a massive invasion of Europe from England, military planners had little choice but to stage units around the country with those that would land first nearest to the embarkation point. As a result of FUSAG's having been placed in the south-east, German intelligence would (and did) deduce that the centre of the invasion force was opposite Calais, the point on the French coast closest to England and therefore a likely landing point.

To facilitate this deception, additional buildings were constructed; dummy aircraft and landing craft were placed around possible embarkation points. Patton paid many of these a visit along with a photographer. Contrary to popular belief, there was no use of other dummy vehicles, such as inflatable tanks, in large part due to Strangeways' refusal to implement widespread physical deception.[12][21] It is thought that the Army encouraged the idea that these dummies were used to draw attention away from some of the other means of deception, such as turned agents.[21] In any case, the Allies overestimated the Germans' abilities to conduct aerial surveillance, so many of the props were never constructed. Patton was photographed visiting the props that were mocked up on regular occasions.

A deception of such a size required input from many organisations, including MI5, MI6, SHAEF via Ops B, and the armed services. Information from the various deception agencies was organized by and channelled through the London Controlling Section under the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel John Bevan.

Fortitude South II

On July 20, Ops (B) took over control of Fortitude South from R Force. Earlier in the previous month, they had begun work on a follow up to the operation.[22] Their new story centered on the idea that Eisenhower had decided to defeat the Germans through the existing beachhead. As a result, elements of FUSAG had been detached and sent to reinforce Normandy and instead a second, smaller, Second American Army Group (SUSAG) would be formed to threaten the Pas-de-Calais.[23]

The plan met some criticism; first of all, there was opposition to the creation of so many fictional US formations in the face of a known manpower shortage in America. Secondly, the plan reduced the threat to Pas-de-Calais and so the Fifteenth Army might be moved to reinforce Normandy. As with its predecessor, in late June Strangeways re-wrote the operation to ensure the focus remained on Calais.[23] In his version, the Normandy beachhead was not as successful, and Eisenhower had taken elements of FUSAG to reinforce its efforts. FUSAG would be rebuilt with newly arrived US formations with the aim of landing in France toward the end of July.[24]

Impact

By 28 September 1944 the Allies had agreed to end the Fortitude deception, moving to operational deceptions in the field under the overall charge of Ops (B).[25]

The Allies were able to judge how well Fortitude was working thanks to Ultra, signals intelligence obtained by breaking German codes and ciphers. On June 1, a decrypted transmission by Hiroshi Ōshima (the Japanese ambassador) to his government recounting a recent conversation with Hitler confirmed the effectiveness of Fortitude. When asked for his thoughts on the Allied battle plan, Hitler had said, "I think that diversionary actions will take place in a number of places - against Norway, Denmark, the southern part of western France, and the French Mediterranean coast".[26] Adding that he expected the Allies to subsequently attack in force across the Straits of Dover.[26]

They maintained the pretense of FUSAG and other forces threatening Pas de Calais for some considerable time after D-Day, possibly even as late as September 1944. This was vital to the success of the Allied plan, since it forced the Germans to keep most of their reserves bottled up waiting for an attack on Calais that never came, thereby allowing the Allies to maintain and build upon their marginal foothold in Normandy.

During the course of Fortitude, the almost complete lack of German aerial reconnaissance, together with the absence of uncontrolled German agents in Britain, came to make physical deception almost irrelevant. The unreliability of the "diplomatic leaks" resulted in their discontinuance. The majority of deception was carried out by means of false wireless traffic and through German double agents. The latter proved to be by far the most significant.

Reasons for success

The operation was successful for several reasons:

- The long term view taken by British Intelligence to cultivate double agents as channels of disinformation to the enemy.

- The use of Ultra decrypts of machine-encrypted messages between the Abwehr and the German High Command, which quickly indicated the effectiveness of deception tactics. This is one of the early uses of a closed-loop deception system. The messages were usually encrypted by Fish rather than Enigma machines.

- R.V. Jones, the Assistant Director Intelligence (Science) at the British Air Ministry insisted for reasons of tactical deception that for every radar station attacked within the real invasion area, two were to be attacked outside it.

- The extensive nature of the German Intelligence machinery, and the rivalry amid the various elements.

- General George S. Patton was the leader the Germans feared the most, and they considered him the Allies' best general.[27] Therefore, the German High Command believed he would lead the attack.

In fiction

Eye of the Needle is a novel (and subsequent movie) about a Nazi spy figuring out the Allied deception and racing to let the German leadership know. Another book, The Unlikely Spy, is a novel that focuses on Allied attempts to carry out Fortitude, as well as a German agent's race to discover the true plans. Blackout, as well as its sequel All Clear, is a novel about time-travelling historians who are studying the events of the Battle of Britain. One of the historians, posing as an American journalist, ends up working for Operation Fortitude. Overlord, Underhand (2013), by the American author Robert P. Wells (novelist) is a fictionalized retelling of the Juan Pujol (Agent Garbo) double-agent story from the Spanish Civil War through 1944, examining his role in MI5's Double-Cross System in selling "Operation Fortitude" to the German High Command. ISBN 978-1-63068-019-0.

Notes

- ↑ SHAEF was offered a list of names to choose from; Bulldog, Axehead, Swordhilt, Fortitude and Ignite

References

- 1 2 Jablonsky 1991

- 1 2 Brown 1975, pp. 1–10

- 1 2 3 Levine (2011), p. 202

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 531

- 1 2 3 4 Levine (2011), pp. 203–204

- 1 2 Holt (2004), p. 532

- 1 2 Holt (2004), p. 533

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 534

- 1 2 3 Levine (2011), pp. 205–206

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 535

- 1 2 Levine (2011), p. 208

- 1 2 Holt (2004), pp. 536–37

- 1 2 3 Levine (2011), p. 206

- 1 2 Levine (2011), p. 207

- 1 2 Sexton 1983, p. 112

- ↑ Holt 2004, p. 486

- 1 2 3 4 Cave Brown 1975

- ↑ Ambrose, Stephen, D-Day June 6th, 1944 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994) p. 82

- ↑ Hesketh, p. 167

- 1 2 Latimer 2001, pp. 218–232

- 1 2 Gawne (2002), p.

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 584

- 1 2 Holt (2004), p. 585

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 586

- ↑ Holt (2004), p. 630

- 1 2 Holt 2004, pp. 565–566

- ↑ Beevor (2012), p. 571

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Fortitude. |

- Cave Brown, Anthony (1975), Bodyguard of Lies: The Extraordinary True Story Behind D-Day, Harpercollins, ISBN 978-0060105518

- Beevor, Antony (2012), The Second World War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0297844976

- Delmer, Sefton, The Counterfeit Spy (Hutchinson, London, 1972)

- Gawne, Jonathan, Ghosts of the ETO (American Tactical Deception Units in the European Theater, 1944–1945)(Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2002)

- Howard, Sir Michael, Strategic Deception (British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 5) (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1990)

- Holt, Thaddeus, The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War (Scribner, New York, 2004)

- Harris, Tomas, GARBO, The Spy Who Saved D-Day, Richmond, Surrey, England: Public Record Office, 2000, ISBN 1-873162-81-2

- Hesketh, Roger (2000). Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN 1-58567-075-8.

- Latimer, Jon, Deception in War, Overlook Press, New York, 2001 ISBN 978-1-58567-381-0

- Levine, Joshua, Operation Fortitude: the Story of the Spy Operation that Saved D-Day, London: Collins, 2011, ISBN 978-0-00-731353-2

- Marks, Leo (1998). Between Silk and Cyanide: A Codemaker's War 1941–1945. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-653063-X.

- Sexton, Donal J. (1983). "Phantoms of the North: British Deceptions in Scandinavia, 1941–1944". Military Affairs. Society for Military Histor. 47 (3): 109–114. doi:10.2307/1988080. ISSN 0026-3931.