American airborne landings in Normandy

| American airborne landings in Normandy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Normandy landings | |||||||

Map of Operation Neptune showing final airborne routes | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

(airlifted) 13,100 paratroopers 3,900 glider troops 5,700 USAAF aircrew |

36,600 (7th Army) 17,300 (OKW Reserve)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

(campaign) 1,003 killed 2,657 wounded 4,490 missing — Airborne losses only |

(whole campaign, not just against airborne units) 21,300 killed, wounded, and missing | ||||||

The American airborne landings in Normandy were the first United States combat operations during Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy by the Western Allies on June 6, 1944 during World War II. Around 13,100 American paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne and 101st Airborne Divisions made night parachute drops early on D-Day, June 6, followed by 3,937 glider troops flown in by day.[2] As the opening maneuver of Operation Neptune (the assault operation for Overlord) the American airborne divisions were delivered to the continent in two parachute and six glider missions.

Both divisions were part of the U.S. VII Corps and provided it support in its mission of capturing Cherbourg as soon as possible to provide the Allies with a port of supply. The specific missions of the airborne divisions were to block approaches into the vicinity of the amphibious landing at Utah Beach, to capture causeway exits off the beaches, and to establish crossings over the Douve River at Carentan to assist the U.S. V Corps in merging the two American beachheads.

The assault did not succeed in blocking the approaches to Utah for three days. Numerous factors played a part, most of which dealt with excessive scattering of the drops. Despite this, German forces were unable to exploit the chaos. Many German units made a tenacious defense of their strong-points, but all were systematically defeated within the week.

Background

Except where footnoted, information in this article is from the USAF official history: Warren, Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater

Plans and revisions

Plans for the invasion of Normandy went through several preliminary phases throughout 1943, during which the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) allocated 13½ U.S. troop carrier groups to an undefined airborne assault. The actual size, objectives, and details of the plan were not drawn up until after General Dwight D. Eisenhower became Supreme Allied Commander in January 1944. In mid-February Eisenhower received word from Headquarters U.S. Army Air Forces that the TO&E of the C-47 Skytrain groups would be increased from 52 to 64 aircraft (plus nine spares) by April 1 to meet his requirements. At the same time the commander of the U.S. First Army, Lieutenant General Omar Nelson Bradley, won approval of a plan to land two airborne divisions on the Cotentin Peninsula, one to seize the beach causeways and block the eastern half at Carentan from German reinforcements, the other to block the western corridor at La Haye-du-Puits in a second lift. The exposed and perilous nature of the La Haye de Puits mission was assigned to the veteran U.S. 82nd Airborne Division ("The All-Americans"), commanded by Major General Matthew Ridgway, while the causeway mission was given to the untested U.S. 101st Airborne Division ("The Screaming Eagles"), which received a new commander in March, Major General Maxwell D. Taylor, replacing Major General William Lee, who suffered from a heart attack and returned to the United States.

Bradley insisted that 75 per cent of the airborne assault be delivered by gliders for concentration of forces. Because it would be unsupported by naval and corps artillery, the commander of the 82nd Airborne also wanted a glider assault to deliver his organic artillery. The use of gliders was planned until April 18, when tests under realistic conditions resulted in excessive accidents and destruction of many gliders. On April 28 the plan was changed; the entire assault force would be inserted by parachute drop at night in one lift, with gliders providing reinforcement during the day.

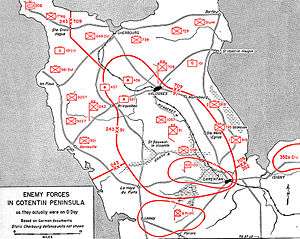

The Germans, who had neglected to fortify Normandy, began constructing defenses and obstacles against airborne assault in the Cotentin, including specifically the planned drop zones of the 82nd. At first no change in plans were made, but when significant German forces were moved into the Cotentin in mid-May, the drop zones of the 82nd were relocated, even though detailed plans had already been formulated and training had proceeded based on them.

Just ten days before D-Day, a compromise was reached. Because of the heavier German presence, First Army wanted the 82nd landed close to the 101st for mutual support if needed. VII Corps, however, wanted the drops made west of the Merderet to seize a bridgehead. On May 27 the drop zones were relocated 10 miles (16 km) east of Le Haye-du-Puits along both sides of the Merderet. The 101st Airborne's 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), which had originally been given the task of capturing Sainte-Mère-Église, was shifted to protect the Carentan flank, and the capture of Sainte-Mère-Église was assigned to the 505th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd.

For the troop carriers, experiences in the Allied invasion of Sicily dictated a route that avoided Allied naval forces and German anti-aircraft defenses along the eastern shore of the Cotentin. On April 12 a route was approved that would depart England at Portland Bill, fly at low altitude southwest over water, then turn 90 degrees to the southeast and come in "by the back door" over the western coast. At the initial point the 82nd would continue straight to La Haye-du-Puits, and the 101st would make a small left turn and fly to Utah Beach. The plan called for a right turn after drops and a return on the reciprocal route.

However the change in drop zones on May 27 and the increased size of German defenses made the risk to the planes from ground fire much greater, and the routes were modified so that the 101st would fly a more southerly ingress route along the Douve River (which would also provide a better visual landmark at night for the inexperienced troop carrier pilots). Over the reluctance of the naval commanders, exit routes from the drop zones were changed to fly over Utah Beach, then northward in a 10 miles (16 km) wide "safety corridor", then northwest above Cherbourg. As late as May 31 routes for the glider missions were changed to avoid overflying the peninsula in daylight.

Preparations

IX Troop Carrier Command (TCC) was formed in October 1943 to carry out the airborne assault mission in the invasion. Brigadier General Paul T. Williams, who had commanded the troop carrier operations in Sicily and Italy, took command in February 1944. The TCC command and staff officers were an excellent mix of combat veterans from those earlier assaults, and a few key officers were held over for continuity.

The 14 groups assigned to IX TCC were a mixture of experience. Four had seen significant combat in the Twelfth Air Force. Four had no combat experience but had trained together for more than a year in the United States. Four others had been in existence less than nine months and arrived in the United Kingdom one month after training began. One had experience only as a transport (cargo carrying) group and the last had been recently formed.

Joint training with airborne troops and an emphasis on night formation flying began at the start of March. The veteran 52nd Troop Carrier Wing (TCW), wedded to the 82nd Airborne, progressed rapidly and by the end of April had completed several successful night drops. The 53rd TCW, working with the 101st, also progressed well (although one practice mission on April 4 in poor visibility resulted in a badly scattered drop) but two of its groups concentrated on glider missions. By the end of April joint training with both airborne divisions ceased when Taylor and Ridgway deemed that their units had jumped enough. The 50th TCW did not begin training until April 3 and progressed more slowly, then was hampered when the troops ceased jumping.

A divisional night jump exercise for the 101st Airborne scheduled for May 7, Exercise Eagle, was postponed to May 11-May 12 and became a dress rehearsal for both divisions. The 52nd TCW, carrying only two token paratroopers on each C-47, performed satisfactorily although the two lead planes of the 316th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) collided in mid-air, killing 14 including the group commander, Col. Burton R. Fleet. The 53rd TCW was judged "uniformly successful" in its drops. The lesser-trained 50th TCW, however, got lost in haze when its pathfinders failed to turn on their navigation beacons. It continued training till the end of the month with simulated drops in which pathfinders guided them to drop zones. The 315th and 442d Groups, which had never dropped troops until May and were judged the command's "weak sisters", continued to train almost nightly, dropping paratroopers who had not completed their quota of jumps. Three proficiency tests at the end of the month, making simulated drops, were rated as fully qualified. The inspectors, however, made their judgments without factoring that most of the successful missions had been flown in clear weather.

By the end of May 1944, the IX Troop Carrier Command had available 1,207 C-47 Skytrain troop carrier airplanes and was one-third overstrength, creating a strong reserve. Three quarters of the planes were less than one year old on D-Day, and all were in excellent condition. Engine problems during training had resulted in a high number of aborted sorties, but all had been replaced to eliminate the problem. All matériel requested by commanders in IX TCC, including armor plating, had been received with the exception of self-sealing fuel tanks, which Chief of the Army Air Forces General Henry H. Arnold had personally rejected because of limited supplies.

Crew availability exceeded numbers of aircraft, but 40 per cent were recent-arriving crews or individual replacements who had not been present for much of the night formation training. As a result, 20 per cent of the 924 crews committed to the parachute mission on D-Day had minimum night training and fully three-fourths of all crews had never been under fire. Over 2,100 CG-4 Waco gliders had been sent to the United Kingdom, and after attrition during training operations, 1,118 were available for operations, along with 301 Airspeed Horsa gliders received from the British. Trained crews sufficient to pilot 951 gliders were available, and at least five of the troop carrier groups intensively trained for glider missions.

Because of the requirement for absolute radio silence and a study that warned that the thousands of Allied aircraft flying on D-Day would break down the existing system, plans were formulated to mark aircraft including gliders with black-and-white stripes to facilitate aircraft recognition. Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, approved the use of the recognition markings on May 17.

For the troop carrier aircraft this was in the form of three white and two black stripes, each two feet (60 cm) wide, around the fuselage behind the exit doors and from front to back on the outer wings. A test exercise was flown by selected aircraft over the invasion fleet on June 1, but to maintain security, orders to paint stripes were not issued until June 3.

Opposing forces

- U.S. VII Corps

- IX Troop Carrier Command

- 50th Troop Carrier Wing

- 52nd Troop Carrier Wing

- 53rd Troop Carrier Wing

- German Seventh Army

- 91st Air Landing Division

- 243rd Infantry Division

- 709th Infantry Division

- 6th Parachute Regiment

Pathfinders

The 300 men of the pathfinder companies were organized into teams of 14-18 paratroops each, whose main responsibility would be to deploy the ground beacon of the Rebecca/Eureka transponding radar system, and set out holophane marking lights. The Rebecca, an airborne sender-receiver, indicated on its scope the direction and approximate range of the Eureka, a responsor beacon. The paratroops trained at the school for two months with the troop carrier crews, but although every C-47 in IX TCC had a Rebecca interrogator installed, to keep from jamming the system with hundreds of signals, only flight leads were authorized to use it in the vicinity of the drop zones.

Despite many early failures in its employment, the Eureka-Rebecca system had been used with high accuracy in Italy in a night drop of the 82nd Airborne to reinforce the U.S. Fifth Army during the Allied invasion of Italy in September 1943. However, a shortcoming of the system was that within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the ground emitter, the signals merged into a single blip in which both range and bearing were lost. The system was designed to steer large formations of aircraft to within a few miles of a drop zone, at which point the holophane marking lights or other visual markers would guide completion of the drop.

Each drop zone (DZ) had a serial of three C-47 aircraft assigned to locate the DZ and drop pathfinder teams, who would mark it. The serials in each wave were to arrive at six-minute intervals. The pathfinder serials were organized in two waves, with those of the 101st Airborne arriving a half-hour before the first scheduled assault drop. These would be the first U.S. and possibly the first Allied troops to land in the invasion. The three pathfinder serials of the 82nd Airborne were to begin their drops as the final wave of 101st Airborne paratroopers landed, thirty minutes ahead of the first 82nd Airborne drops.

D-Day results

Efforts of the early wave of pathfinder teams to mark the drop zones were partially ineffective. The first serial, assigned to DZ A, missed its zone and set up a mile away near St. Germain-de-Varreville. The team was unable to get either its amber halophane lights or its Eureka beacon working until the drop was well in progress. Although the second pathfinder serial had a plane ditch in the sea en route, the remainder dropped two teams near DZ C, but most of their marker lights were lost in the ditched airplane. They managed to set up a Eureka beacon just before the assault force arrived but were forced to use a hand held signal light which was not seen by some pilots. The planes assigned to DZ D along the Douve River failed to see their final turning point and flew well past the zone. Returning from an unfamiliar direction, they dropped 10 minutes late and 1 mile (1.6 km) off target. The drop zone was chosen after the 501st PIR's change of mission on May 27 and was in an area identified by the Germans as a likely landing area. Consequently so many Germans were nearby that the pathfinders could not set out their lights and were forced to rely solely on Eureka, which was a poor guide at short range.

The pathfinders of the 82nd Airborne had similar results. The first serial, bound for DZ O near Sainte-Mère-Église, flew too far north but corrected its error and dropped near its DZ. It made the most effective use of the Eureka beacons and holophane marking lights of any pathfinder team. The planes bound for DZ N south of Sainte-Mère-Église flew their mission accurately and visually identified the zone but still dropped the teams a mile southeast. They landed among troop areas of the German 91st Division and were unable to reach the DZ. The teams assigned to mark DZ T northwest of Sainte-Mère-Église were the only ones dropped with accuracy, and while they deployed both Eureka and BUPS, they were unable to show lights because of the close proximity of German troops. Altogether, four of the six drops zones could not display marking lights.

The pathfinder teams assigned to Drop Zones C (101st) and N (82nd) each carried two BUPS beacons. The units for DZ N were intended to guide in the parachute resupply drop scheduled for late on D-Day, but the pair of DZ C were to provide a central orientation point for all the SCR-717 radars to get bearings. However the units were damaged in the drop and provided no assistance.

Combat jumps

Mission profile

The assault lift (one air transport operation) was divided into two missions, "Albany" and "Boston", each with three regiment-sized landings on a drop zone. The drop zones of the 101st were northeast of Carentan and lettered A, C, and D from north to south (Drop Zone B had been that of the 501st PIR before the changes of May 27). Those of the 82nd were west (T and O, from west to east) and southwest (Drop Zone N) of Sainte-Mère-Eglise.

Each parachute infantry regiment (PIR), a unit of approximately 1800 men organized into three battalions, was transported by three or four serials, formations containing 36, 45, or 54 C-47s, and separated from each other by specific time intervals. The planes, sequentially designated within a serial by chalk numbers (literally numbers chalked on the airplanes to aid paratroopers in boarding the correct airplane), were organized into flights of nine aircraft, in a formation pattern called "vee of vee's" (vee-shaped elements of three planes arranged in a larger vee of three elements), with the flights flying one behind the other. The serials were scheduled over the drop zones at six-minute intervals. The paratroopers were divided into sticks, a plane load of troops numbering 15-18 men.

To achieve surprise, the parachute drops were routed to approach Normandy at low altitude from the west. The serials took off beginning at 22:30 on June 5, assembled into formations at wing and command assembly points, and flew south to the departure point, code-named "Flatbush". There they descended and flew southwest over the English Channel at 500 feet (150 m) MSL to remain below German radar coverage. Each flight within a serial was 1,000 feet (300 m) behind the flight ahead. The flights encountered winds that pushed them five minutes ahead of schedule, but the effect was uniform over the entire invasion force and had negligible effect on the timetables. Once over water, all lights except formation lights were turned off, and these were reduced to their lowest practical intensity.

Twenty-four minutes 57 miles (92 km) out over the channel, the troop carrier stream reached a stationary marker boat code-named "Hoboken" and carrying a Eureka beacon, where they made a sharp left turn to the southeast and flew between the Channel Islands of Guernsey and Alderney. Weather over the channel was clear; all serials flew their routes precisely and in tight formation as they approached their initial points on the Cotentin coast, where they turned for their respective drop zones. The initial point for the 101st at Portbail, code-named "Muleshoe", was approximately 10 miles (16 km) south of that of the 82d, "Peoria", near Flamanville.

Scattered drops

Despite precise execution over the channel, numerous factors encountered over the Cotentin Peninsula disrupted the accuracy of the drops, many encountered in rapid succession or simultaneously. These included:[3][4][5]

- C-47 configuration, including severe overloading, use of drag-inducing parapacks, and shifting centers of gravity,

- a lack of navigators on 60 percent of aircraft, forcing navigation by pilots when formations broke up,

- radio silence that prevented warnings when adverse weather was encountered,

- a solid cloud bank at penetration altitude (1,500 feet (460 m)), obscuring the entire western half of the 22 miles (35 km) wide peninsula, thinning to broken clouds over the eastern half,

- an opaque ground fog over many drop zones,

- German antiaircraft fire ("flak"),

- limitations of the Rebecca/Eureka transponding radar system used to guide serials to their drop zones,

- emergency usage of Rebecca by numerous lost aircraft, jamming the system,

- unmarked or poorly marked drop zones,

- drop runs by some C-47s that were above or below the designated 700 feet (210 m) drop altitude, or in excess of the 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) drop speed, and

- second or third passes over an area searching for drop zones.

Flak from German anti-aircraft guns resulted in planes either going under or over their prescribed altitudes. Some of the men who jumped from planes at lower altitudes were injured when they hit the ground because of their chutes not having enough time to slow their descent, while others who jumped from higher altitudes reported a terrifying descent of several minutes watching tracer fire streaking up towards them.

Of the 20 serials making up the two missions, nine plunged into the cloud bank and were badly dispersed. Of the six serials which achieved concentrated drops, none flew through the clouds. However the primary factor limiting success of the paratroop units, because it magnified all the errors resulting from the above factors, was the decision to make a massive parachute drop at night, a concept that was not again used in three subsequent large-scale airborne operations. This was further illustrated when the same troop carrier groups flew a second lift later that day with precision and success under heavy fire.[6]

First wave: Mission Albany

Paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division "Screaming Eagles" jumped first on June 6, between 00:48 and 01:40 British Double Summer Time. 6,928 troops were carried aboard 432 C-47s of mission "Albany" organized into 10 serials. The first flights, inbound to DZ A, were not surprised by the bad weather, but navigating errors and a lack of Eureka signal caused the 2nd Battalion 502nd PIR to come down on the wrong drop zone. Most of the remainder of the 502nd jumped in a disorganized pattern around the impromptu drop zone set up by the pathfinders near the beach. Two battalion commanders took charge of small groups and accomplished all of their D-Day missions. The division's parachute artillery experienced one of the worst drops of the operation, losing all but one howitzer and most of its troops as casualties.

The three serials carrying the 506th PIR were badly dispersed by the clouds, then subjected to intense antiaircraft fire. Even so, 2/3 of the 1st Battalion was dropped accurately on DZ C. The 2nd Battalion, much of which had dropped too far west, fought its way to the Haudienville causeway by mid-afternoon but found that the 4th Division had already seized the exit. The 3rd Battalion of the 501st PIR, also assigned to DZ C, was more scattered, but took over the mission of securing the exits. A small unit reached the Pouppeville exit at 0600 and fought a six-hour battle to secure it, shortly before 4th Division troops arrived to link up.

The 501st PIR's serial also encountered severe flak but still made an accurate jump on Drop Zone D. Part of the DZ was covered by pre-registered German fires that inflicted heavy casualties before many troops could get out of their chutes. Among the killed were two of the three battalion commanders and one of their executive officers. A group of 150 troops captured the main objective, the la Barquette lock, by 04:00. A staff officer put together a platoon and achieved another objective by seizing two foot bridges near la Porte at 04:30. The 2nd Battalion landed almost intact on DZ D but in a day-long battle failed to take Saint-Côme-du-Mont and destroy the highway bridges over the Douve.

The glider battalions of the 101st's 327th Glider Infantry Regiment were delivered by sea and landed across Utah Beach with the 4th Infantry Division. On D-Day its third battalion, the 1st Battalion 401st GIR, landed just after noon and bivouacked near the beach. By the evening of June 7 the other two battalions were assembled near Sainte Marie du Mont.

Second wave: Mission Boston

The 82nd Airborne's drop, mission "Boston", began at 01:51. It was also a lift of 10 serials organized in three waves, totaling 6,420 paratroopers carried by 369 C-47s. The C-47s carrying the 505th did not experience the difficulties that had plagued the 101st's drops. Pathfinders on DZ O turned on their Eureka beacons as the first 82nd serial crossed the initial point and lighted holophane markers on all three battalion assembly areas. As a result the 505th enjoyed the most accurate of the D-Day drops, half the regiment dropping on or within a mile of its DZ, and 75 per cent within 2 miles (3.2 km).

The other regiments were more significantly dispersed. The 508th experienced the worst drop of any of the PIRs, with only 25 per cent jumping within a mile of the DZ. Half the regiment dropped east of the Merderet, where it was useless to its original mission.[7] The 507th PIR's pathfinders landed on DZ T, but because of Germans nearby, marker lights could not be turned on. Approximately half landed nearby in grassy swampland along the river. Estimates of drowning casualties vary from "a few"[8] to "scores"[9] (against an overall D-Day loss in the division of 156 killed in action), but much equipment was lost and the troops had difficulty assembling.

Timely assembly enabled the 505th to accomplish two of its missions on schedule. With the help of a Frenchman who led them into the town, the 3rd Battalion captured Sainte-Mère-Église by 0430 against "negligible opposition" from German artillerymen.[10] The 2nd Battalion established a blocking position on the northern approaches to Sainte-Mère-Église with a single platoon while the rest reinforced the 3rd Battalion when it was counterattacked at mid-morning. The 1st Battalion did not achieve its objectives of capturing bridges over the Merderet at la Fière and Chef-du-Pont, despite the assistance of several hundred troops from the 507th and 508th PIRs.

None of the 82nd's objectives of clearing areas west of the Merderet and destroying bridges over the Douve were achieved on D-Day. However one makeshift battalion of the 508th PIR seized a small hill near the Merderet and disrupted German counterattacks on Chef-du-Pont for three days, effectively accomplishing its mission. Two company-sized pockets of the 507th held out behind the German center of resistance at Amfreville until relieved by the seizure of the causeway on June 9.

D-Day glider landings

Pre-dawn assaults

Two pre-dawn glider landings, missions "Chicago" (101st) and "Detroit" (82nd), each by 52 CG-4 Waco gliders, landed anti-tank guns and support troops for each division. The missions took off while the parachute landings were in progress and followed them by two hours, landing at about 0400, 2 hours before dawn. Chicago was an unqualified success, with 92 per cent landing within 2 miles (3.2 km) of target. Detroit was disrupted by the same cloud bank that had bedevilled the paratroops and only 62 per cent landed within 2 miles (3.2 km). Even so, both missions provided heavy weapons that were immediately placed into service. Only eight passengers were killed in the two missions, but one of those was the assistant division commander of the 101st Airborne, Brigadier General Don Pratt. Five gliders in the 82nd's serial, cut loose in the cloud bank, remaining missing after a month.

Evening reinforcement missions

On the evening of D-Day two additional glider operations, mission "Keokuck" and mission "Elmira", brought in additional support on 208 gliders. Operating on British Double Summer Time, both arrived and landed before dark. Both missions were heavily escorted by P-38, P-47, and P-51 fighters.

Keokuck was a reinforcement mission for the 101st Airborne consisting of a single serial of 32 tugs and gliders that took off beginning at 18:30. It arrived at 20:53, seven minutes early, coming in over Utah Beach to limit exposure to ground fire, into a landing zone clearly marked with yellow panels and green smoke. German forces around Turqueville and Saint Côme-du-Mont, 2 miles (3.2 km) on either side of Landing Zone E, held their fire until the gliders were coming down, and while they inflicted some casualties, were too distant to cause much harm. Although only five landed on the LZ itself and most were released early, the Horsa gliders landed without serious damage. Two landed within German lines. The mission is significant as the first Allied daylight glider operation, but was not significant to the success of the 101st Airborne.[11]

Elmira was essential to the 82nd Airborne, however, delivering two battalions of glider artillery and 24 howitzers to support the 507th and 508th PIRs west of the Merderet. It consisted of four serials, the first pair to arrive ten minutes after Keokuck, the second pair two hours later at sunset. The first gliders, unaware that the LZ had been moved to Drop Zone O, came under heavy ground fire from German troops who occupied part of Landing Zone W. The C-47s released their gliders for the original LZ, where most delivered their loads intact despite heavy damage.

The second wave of mission Elmira arrived at 22:55, and because no other pathfinder aids were operating, they headed for the Eureka beacon on LZ O. That wave too came under severe ground fire as it passed directly over German positions. One serial released early and came down near the German lines, but the second came down on Landing Zone O. Nearly all of both battalions joined the 82nd Airborne by morning, and 15 guns were in operation on June 8.[12]

Follow-up landing and supply operations

325th Glider Infantry Regiment

Two additional glider missions ("Galveston" and "Hackensack") were made just after daybreak on June 7, delivering the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment to the 82nd Airborne. The hazards and results of mission Elmira resulted in a route change over the Douve River valley that avoided the heavy ground fire of the evening before, and changed the landing zone to LZ E, that of the 101st Airborne Division. The first mission, Galveston, consisted of two serials carrying the 325th's 1st Battalion and the remainder of the artillery. Consisting of 100 glider-tug combinations, it carried nearly a thousand men, 20 guns, and 40 vehicles and released at 06:55. Small arms fire harried the first serial but did not seriously endanger it. Low releases resulted in a number of accidents and 100 injuries in the 325th (17 fatal). The second serial hit LZ W with accuracy and few injuries.

Mission Hackensack, bringing in the remainder of the 325th, released at 08:51. The first serial, carrying all of the 2nd Battalion and most of the 2nd Battalion 401st GIR (the 325th's "third battalion"), landed by squadrons in four different fields on each side of LZ W, one of which came down through intense fire. 15 troops were killed and 60 wounded, either by ground fire or by accidents caused by ground fire. The last glider serial of 50 Wacos, hauling service troops, 81 mm mortars, and one company of the 401st, made a perfect group release and landed at LZ W with high accuracy and virtually no casualties. By 10:15, all three battalions had assembled and reported in. With 90 per cent of its men present, the 325th GIR became the division reserve at Chef-du-Pont.

Airborne resupply

Two supply parachute drops, mission "Freeport" for the 82nd and mission "Memphis" intended for the 101st, were dropped on June 7. All of these operations came in over Utah Beach but were nonetheless disrupted by small arms fire when they overflew German positions, and virtually none of the 101st's supplies reached the division. Fourteen of the 270 C-47s on the supply drops were lost compared to only seven of the 511 glider tugs shot down.

In the week following, six resupply missions were flown on call by the 441st and 436th Troop carrier Groups, with 10 C-47's making parachute drop and 24 towing gliders. This brought the final total of IX Troop Carrier Command sorties during Operation Neptune to 2,166, with 533 of those being glider sorties.

Ground combat involving U.S. airborne forces

This section summarizes all ground combat in Normandy by the U.S. airborne divisions. The U.S. Army does not designate the point in time in which the airborne assault ended and the divisions that fought it conducted a conventional infantry campaign.

After 24 hours, only 2,500 of the 6,000 men in 101st were under the control of division headquarters. The 82nd had consolidated its forces on Sainte-Mère-Église, but significant pockets of troops were isolated west of the Merderet, some of which had to hold out for several days. The dispersal of the American airborne troops, and the nature of the hedgerow terrain, had the effect of confusing the Germans and fragmenting their response. In addition, the Germans' defensive flooding, in the early stages, also helped to protect the Americans' southern flank. The 4th Infantry Division had landed and moved off Utah Beach, with the 8th Infantry surrounding a German battalion on the high ground south of Sainte-Mère-Église, and the 12th and 22nd Infantry moving into line northeast of the town. The biggest anxiety for the airborne commanders was in linking up with the widely scattered forces west of the Merderet.

Many continued to roam and fight behind enemy lines for up to 5 days. The Air Force Historical Study on the operation notes that several hundred paratroopers scattered without organization far from the drop zones were "quickly mopped up", despite their valor and inherent toughness, by small German units that possessed unit cohesion. Most consolidated into small groups, however, rallied by NCOs and officers up to and including battalion commanders, and many were hodgepodges of troopers from different units. Particularly in the areas of the 507th and 508th PIRs, these isolated groupings, while fighting for their own survival, played an important role in the overall clearance of organized German resistance.

On June 6, the German 6th Parachute Regiment (FJR6), commanded by Oberst Friedrich August von der Heydte,[13] (FJR6) advanced two battalions, I./FJR6 to Sainte-Marie-du-Mont and II./FJR6 to Sainte-Mère-Église, but faced with the overwhelming numbers of the two U.S. divisions, withdrew. I./FJR6 attempted to force its way through U.S. forces half its size along the Douve River but was cut off and captured almost to the man. Nearby, the 506th PIR conducted a reconnaissance-in-force with two understrength battalions to capture Saint-Côme-du-Mont but although supported by several tanks, was stopped near Angoville-au-Plain. In the 82nd Airborne's area, a battalion of the 1058th Grenadier Regiment supported by tanks and other armored vehicles counterattacked Sainte-Mère-Église the same morning but were stopped by a reinforced company of M4 Sherman tanks from the 4th Division. The German armor retreated and the infantry was routed with heavy casualties by a coordinated attack of the 2nd Battalion 505th and the 2nd Battalion 8th Infantry.

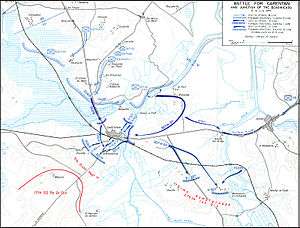

101st units maneuvered on June 8 to envelop Saint-Côme-du-Mont, pushing back FJR6, and consolidated its lines on June 9. VII Corps gave the division the task of taking Carentan. The 502nd experienced heavy combat on the causeway on June 10. The next day it attacked the town, supported by the 327th GIR attacking from the east. The 506th PIR passed through the exhausted 502nd and attacked into Carentan on June 12, defeating the rear guard left by the German withdrawal. On June 13 German forces using assault guns, tanks, and infantry of the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division's 37th SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment, along III./FJR6, attacked the 101st southwest of Carentan. The Germans pushed back the left of the U.S. line in a morning-long battle until Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division was sent forward to repel the attack. The 101st was then assigned to the newly arrived U.S. VIII Corps on June 15 in a defensive role before returning to England for rehabilitation.

The 82nd airborne still had not gained control of the bridge across the Merderet by June 9. Its 325th GIR, supported by several tanks, forced a crossing under fire to link up with pockets of the 507th PIR, then extended its line west of the Merderet to Chef-du-Pont. The 505th PIR captured Montebourg Station northwest of Sainte-Mere-Èglise on June 10, supporting an attack by the 4th Division. The 508th PIR attacked across the Douve River at Beuzeville-la-Bastille on June 12 and captured Baupte the next day. On June 14 units of the 101st Airborne linked up with the 508th PIR at Baupte.

The 325th and 505th passed through the 90th Division, which had taken Pont l'Abbé (originally an 82nd objective), and drove west on the left flank of VII Corps to capture Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte on June 16. On June 19 the division was assigned to VIII Corps, and the 507th established a bridgehead over the Douve south of Pont l'Abbé. The 82nd Airborne continued its march towards La Haye-du-Puits, and made its final attack against Hill 122 (Mont Castre) on July 3 in a driving rainstorm. It was "pinched out" of line by the advance of the 90th Infantry Division the next day and went into reserve to prepare to return to England.[14]

Aircraft losses and casualties

Forty-two C-47s were destroyed in two days of operations, although in many cases the crews survived and were returned to Allied control. Twenty-one of the losses were on D-Day during the parachute assault, another seven while towing gliders, and the remaining fourteen during parachute resupply missions.[2] Of the 517 gliders, 222 were Horsa gliders, most of which were destroyed in landing accidents or by German fire after landing. Although a majority of the 295 Waco gliders were repairable for use in future operations, the combat situation in the beachhead did not permit the introduction of troop carrier service units, and 97 per cent of all gliders used in the operation were abandoned in the field.[15]

D-Day casualties for the airborne divisions were calculated in August 1944 as 1,240 for the 101st Airborne Division and 1,259 for the 82nd Airborne. Of those, the 101st suffered 182 killed, 557 wounded, and 501 missing. For the 82nd, the total was 156 killed, 347 wounded, and 756 missing.[16]

Casualties through June 30 were reported by VII Corps as 4,670 for the 101st (546 killed, 2217 wounded, and 1,907 missing), and 4,480 for the 82nd (457 killed, 1440 wounded, and 2583 missing).[17]

German casualties[18] amounted to approximately 21,300 for the campaign. The 6th Parachute Regiment reported approximately 3,000 through the end of July. Divisional totals, which include combat against all VII Corps units, not just airborne, and their reporting dates were:

- 91st Luftlande Div: 2,212 (June 12), 5,000 (July 23)

- 243rd Infantry Div: 8,189 (July 11)

- 709th Infantry Div: 4,000 (June 16)

- 17th SS-Panzergrenadier Div: 1,096 (June 30)

Troop carrier controversy

In his 1962 book, Night Drop: The American Airborne Invasion of Normandy, Army historian S.L.A. Marshall concluded that the mixed performance overall of the airborne troops in Normandy resulted from poor performance by the troop carrier pilots. In coming to that conclusion he did not interview any aircrew nor qualify his opinion to that extent, nor did he acknowledge that British airborne operations on the same night succeeded despite also being widely scattered. Marshall’s original data came from after-action interviews with paratroopers after their return to England in July 1944, which was also the basis of all U.S. Army histories on the campaign written after the war, and which he later incorporated in his own commercial book.[19]

General Omar Bradley[20] blamed "pilot inexperience and anxiety" as well as weather for the failures of the paratroopers. Memoirs by former 101st troopers, notably Donald Burgett (Currahee) and Laurence Critchell (Four Stars of Hell) harshly denigrated the pilots based on their own experiences, implying cowardice and incompetence (although Burgett also praised the Air Corps as "the best in the world"). Later John Keegan (Six Armies in Normandy) and Clay Blair (Ridgway’s Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II) escalated the tone of the criticism, stating that troop carrier pilots were the least qualified in the Army Air Forces, disgruntled, and castoffs.[21] Others critical included Max Hastings (Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy) and James Huston (Out of the Blue: U.S. Army Airborne Operations in World War II). As late as 2003 a prominent history (Airborne: A Combat History of American Airborne Forces by retired Lieutenant General E.M. Flanagan) repeated these and other assertions, all of it laying failures in Normandy at the feet of the pilots.[3]

This criticism primarily derived from anecdotal testimony in the battle-inexperienced 101st Airborne. Criticism from veterans of the 82nd Airborne was not only rare, its commanders Ridgway and Gavin both officially commended the troop carrier groups, as did Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Vandervoort and even one prominent 101st veteran, Captain Frank Lillyman, commander of its pathfinders. Gavin’s commendation said in part:

The accomplishments of the parachute regiments are due to the conscientious and efficient tasks of delivery performed by your pilots and crews. I am aware, as we all are, that your wing suffered losses in carrying out its missions and that a very bad fog condition was encountered inside the west coast of the peninsula. Yet despite this every effort was made for an exact and precise delivery as planned. In most cases this was successful.[4]

The troop carrier pilots in their remembrances and histories admitted to many errors in execution of the drops but denied the aspersions on their character, citing the many factors since enumerated and faulty planning assumptions. Some, such as Martin Wolfe, an enlisted radio operator with the 436th TCG, pointed out that some late drops were caused by the paratroopers, who were struggling to get their equipment out the door until their aircraft had flown by the drop zone by several miles.[22] Others mistook drops made ahead of theirs for their own drop zones and insisted on going early.[23] The TCC personnel also pointed out that anxiety at being new to combat was not confined to USAAF crews. Warren reported that official histories showed 9 paratroopers had refused to jump and at least 35 other uninjured paratroopers were returned to England aboard C-47s.[24] General Gavin reported that many paratroopers were in a daze after the drop, huddling in ditches and hedgerows until prodded into action by veterans.[25] Wolfe noted that although his group had botched the delivery of some units in the night drop, it flew a second, daylight mission on D-Day and performed flawlessly although under heavy ground fire from alerted Germans.

Despite this, controversy did not flare until the assertions reached the general public as a commercial best-seller in Stephen Ambrose's Band of Brothers, particularly in sincere accusations by icons such as Richard Winters. In 1995, following publication of D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, troop carrier historians, including veterans Lew Johnston (314th TCG), Michael Ingrisano Jr. (316th TCG), and former U.S. Marine Corps airlift planner Randolph Hils, attempted to open a dialog with Ambrose to correct errors they cited in D-Day, which they then found had been repeated from the more popular and well-known Band of Brothers. Their frustration with his failure to follow through on what they stated were promises to correct the record, particularly to the accusations of general cowardice and incompetence among the pilots, led them to detailed public rejoinders when the errors continued to be widely asserted, including in a History Channel broadcast April 8, 2001.[5] As recently as 2004, in MHQ: The Quarterly of Military History, the misrepresentations regarding lack of night training, pilot cowardice, and TC pilots being the dregs of the Air Corps were again repeated, with Ambrose being cited as its source.[26]

See also

- Order of battle for the American airborne landings in Normandy

- Operation Tonga, the British and Canadian airborne landings in Normandy

- IX Troop Carrier Command

Footnotes

- ↑ compilation

- 1 2 "Statistical Tables". D-Day: Etats des Lieux. Retrieved 24 June 2007. Includes pathfinders. All statistics, except where otherwise noted, are derived from this source, which referenced Warren.

- 1 2 "An open letter to the airborne community". War Chonicles. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Stephen E. Ambrose World War II Sins". B-26 Marauder Historical Society. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- 1 2 "The Troop Carrier D-Day Flights". AMC Museum. Retrieved 26 June 2007. This is a 12-part work by Lew Johnston, a TC pilot with the 314th TCG.

- ↑ Wolfe, Green Light!, 122.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 54.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 55.

- ↑ Wolfe, Green Light!, 119.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 50-51.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 66.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 68-69.

- ↑ Ambrose, D-Day, pg. 116

- ↑ "The July Offensive". St-Lô. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 100-13. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 53.

- ↑ Harrison, Gordan A. (2002) [1951]. "Airborne Assault". Cross Channel Attack. The United States Army in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 7-4. Retrieved 26 June 2007., Note 34 for 101st, note 55 for 82nd.

- ↑ "Appendix B". Utah to Cherbourg. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 100-12. Retrieved 26 June 2007..

- ↑ compiled at German Order of Battle Normandy

- ↑ "Why Does the NYT Continue to Cite Historian S.L.A. Marshall After the Paper Discredited Him in a Front-Page Story Years Ago?". History News Network George Mason University. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ↑ A General’s Life.

- ↑ Wolfe, Green Light!, 334. Blair also imputed that glider pilots were cowards in general.

- ↑ Wolfe, Green Light, 118, quoting from Four Stars of Hell.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 41.

- ↑ Warren, Airborne Operations, 41, 43, 45.

- ↑ Wolfe, Green Light!, 117.

- ↑ "101st Airborne Division participate in Operation Overlord (sic)". HistoryNet.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

References

- Ambrose, Stephen (1994). D-Day: The Climactic Battle of World War II. Simon and Schuster Paperbacks. ISBN 0-684-80137-X.

- Balkoski, Joseph (2005). Utah Beach: The Amphibious Landing and Airborne Operations on D-Day. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3377-9.

- Buckingham, William F. (2005). D-Day The First 72 Hours. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2842-X.

- Devlin, Gerard M. (1979). Paratrooper – The Saga Of Parachute And Glider Combat Troops During World War II. Robson Books. ISBN 0-312-59652-9.

- Flanagan, E. M. Jr (2002). Airborne – A Combat History Of American Airborne Forces. The Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 0-89141-688-9.

- Harclerode, Peter (2005). Wings Of War – Airborne Warfare 1918–1945. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36730-3.

- Huston, James A. (1998). Out Of The Blue – U.S Army Airborne Operations In World War II. Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-148-X.

- Tugwell, Maurice (1978). Assault From The Sky – The History of Airborne Warfare. Westbridge Books. ISBN 0-7153-9204-2.

- Warren, Dr John C. (1956). Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater. Air University, Maxwell AFB: US Air Force Historical Research Agency. USAF Historical Study 97.

- Weeks, John (1971). Airborne To Battle – A History Of Airborne Warfare 1918–1971. William Kimber & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-7183-0262-1.

External links

- Dropzone Normandy (1944)

- American D-Day: Omaha Beach, Utah Beach & Pointe du Hoc

- German battalion dispositions in Normandy, 5 June 1944

- US Airborne during World War II

- Stephen E. Ambrose World War II sins a thorough examination of the Troop carrier controversy from the TCC point of view, includes detailed explanation of troop carrier terms and procedures

- An open letter to the airborne community another view of the controversy from a TCC historian

- German Order of Battle, a private site well-documented from German records of OB, strength, and casualties

- U.S. Airborne in Cotentin Peninsula

- "The Troop Carrier D-Day Flights", Air Mobility Command Museum

- D-Day Minus One (1945). U.S. Army archive film featuring the roles' of paratroopers and glider troops during the Normandy Invasion. From the Internet Archive, Public domain.