Persepolis (film)

| Persepolis | |

|---|---|

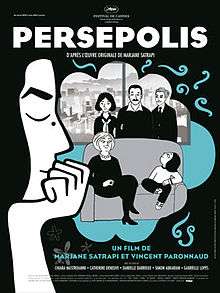

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Olivier Bernet |

| Edited by | Stéphane Roche |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Diaphana Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[1] |

| Country | France |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $7.3 million |

| Box office | $22.8 million |

Persepolis is a 2007 French animated biographical film based on Marjane Satrapi's autobiographical graphic novel of the same name. The film was written and directed by Satrapi with Vincent Paronnaud.[2] The story follows a young girl as she comes of age against the backdrop of the Iranian Revolution. The title is a reference to the historic city of Persepolis.

The film was co-winner of the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival[3][4] and was released in France and Belgium on 27 June. In her acceptance speech, Satrapi said "Although this film is universal, I wish to dedicate the prize to all Iranians."[5] The film was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, but lost to Ratatouille.

Plot

At the airport, Marjane is unable to board a plane to Iran. She then takes a seat and smokes a cigarette. She reflects on her childhood, full of politically driven conflict. As a young girl, Marji lived in Tehran and wanted to be a prophet and a disciple of Bruce Lee. Her childhood ambition is the general uprising against the Shah of Iran. Her middle-class family participates in all the rallies and protests. Marji and a group of friends attempt to attack a young boy named Ramen, whose father, a member of SAVAK, killed Communists for no particular reason. One day, Marji's Uncle Anoush arrives to have dinner with the family after recently being released from his nine-year sentence in prison. Uncle Anoush inspires Marji with his stories of his life on the run from the government, a result of rebelling. Political enemies cease fighting and elections for a new leading power commence. Marji's family's situation does not improve as they are profoundly upset when Islamic Fundamentalists win the elections with 99.99% of the vote and start repressing Iranian society. The government forces women to dress modestly, including wearing a head scarf, and Anoush is rearrested and executed for his political beliefs. Profoundly disillusioned, Marji tries, with her family, to fit into the reality of the intolerant regime. The Iran-Iraq war breaks out and Marji sees for herself the horrors of death and destruction. The Iranian government begins implementing ridiculous laws that create blatant injustices. Marji witnesses her father threatened by rifle-wielding teenaged government officials and watches her critically ill uncle die after an unqualified government-appointed hospital administrator refuses to allow him to travel abroad for medical treatment. The family tries to find solace in secret parties where they enjoy simple pleasures the government has outlawed, including alcohol. As she grows up, Marji begins a life of over-confidence. She refuses to stay out of trouble, secretly buying Western heavy metal music, notably Iron Maiden, on the black market, wearing unorthodox clothing such as a denim jacket, celebrating punk rock and other Western music sensations like Michael Jackson, and openly rebuts a teacher's lies about the abuses of the government.

Fearing her arrest for her outspokenness, Marji's parents send her to a French lycée in Vienna, Austria, where she can be safe and free to express herself. She lives with Catholic nuns and is upset with their discriminatory and judgmental behaviour. Marji doesn't make any friends, and ultimately feels intolerably isolated in a foreign land surrounded by annoyingly superficial people who take their freedom for granted. As the years go by, Marji is thrown out of her temporary shelter for insulting a nun and is driven out into the streets. Marji continues to go from house to house, until ending up in the house of Frau Dr. Schloss, a retired philosophy teacher. One night, her grandmother's voice resonates, telling her to stay true to herself as she leaves a party after lying about her nationality, telling an acquaintance that she was French. Her would-be lover reveals his homosexuality after a failed attempt at sex with Marji. She engages in a passionate love affair with Markus, a debonair native, which ends when she discovers him cheating on her. Marji is accused of stealing Frau Dr. Schloss' brooch, she becomes angered and leaves. She spends the day on a park bench, reflecting upon how cruel Markus was to her. She discovers that she has nowhere to go. She lives on the street for a few months. Eventually, she becomes ill and contracts bronchitis, and almost dies.

Marji recovers in a Viennese hospital and returns to Iran with her family's permission and hopes that the conclusion of the war will improve their quality of life. After spending several days wasting her time watching television, Marji falls into a clinical depression. She attempts suicide by overdosing on medication. She falls asleep and dreams of God and Karl Marx reminding her what is important and encouraging her to live. Her determination is renewed and she begins enjoying life again. Marji attends university classes and parties. She enters into a relationship with a fellow student. Marji notices that her situation has gradually worsened and that Iranian society is more tyrannized than ever. Mass executions for political beliefs and petty religious absurdities have become common, much to Marji's dismay. She and her boyfriend are caught holding hands and their parents are forced to pay a fine to avoid their lashing. Despite Iranian society making living as a student and a woman intolerable, Marji remains rebellious. She resorts to personal survival tactics to protect herself, such as falsely accusing a man of insulting her to avoid being arrested for wearing make up, and marrying her boyfriend to avoid scrutiny by the religious police. Her grandmother is disappointed by Marji's behaviour and berates Marji, telling her that both her grandfather and her uncle died supporting freedom and innocent people, and that she should never forsake them or her family by succumbing to the repressive environment of Iran. Marji, realising her mistake, fixes her mistakes, and her grandmother is pleased to hear that Marji openly confronted the blatant sexist double standard in her university's forum on public morality.

The police raid a party. While the women are arrested, the men escape on the rooftops. One of the men, Nima, unwittingly hesitates before one of them jumps, consequently falling to his death. Her family decides that Marji, after her friend's death and her divorce, leave the country permanently to avoid being targeted by the Iranian authorities as a political dissident. Marji's mother forbids Marji from returning and Marji reluctantly agrees. Marji states that this would be the last time she saw her grandmother who died not long after her departure. Marji is shown collecting her luggage and getting into a taxi. As the taxi drives away from the south terminal of Paris-Orly Airport, the narrative cuts back to the present day. The driver asks Marji where she is from and she replies "Iran," showing that she's kept the promise she made to Anoush and her grandmother that she would remember where she came from and that she would always stay true to herself. She recalls her final memory of her grandmother telling her how she placed jasmine in her brassiere to smell lovely every day.

Cinematography

The film is presented in the black-and-white style of the original graphic novels. Satrapi explains in a bonus feature on the DVD that this was so the place and the characters wouldn't look like foreigners in a foreign country but simply people in a country to show how easily a country can become like Iran. The present-day scenes are shown in color, while sections of the historic narrative resemble a shadow theater show. The design was created by art director and executive producer Marc Jousset. The animation is credited to the Perseprod studio and was created by two specialized studios, Je Suis Bien Content and Pumpkin 3D.

Cast

- Chiara Mastroianni as Marjane

- Catherine Deneuve as Mother

- French version

- Gabriele Lopes as child Marjane

- Danielle Darrieux as Grandmother

- Simon Abkarian as Father

- François Jerosme as Uncle Anouche

- English version

- Amethyste Frezignac as child Marjane

- Gena Rowlands as Grandmother

- Sean Penn as Father

- Iggy Pop (uncredited) as Uncle Anouche

Animation and design

Directed by Christian Desmares, the film was produced by a total of twenty animators. Initially opposed to producing an animated movie due to the high level of difficulty, producers Marc-Antoine Robert and Xavier Regault gave protagonist, Marjane Satrapi, alternative options of film production to avoid animation. As admitted by producer Robert, "I know the new generation of French comic book artists quite well, and I'm afraid of Marjane's. I offered to write an original script for her, because I didn't want to work on an animated movie at all...I knew how complicated it was" (http://www.awn.com/animationworld/persepolis-motion). And yet, despite the difficulty, the producers followed through with Satrapi's wishes and focused on interpreting her life story as depicted in her novel Persepolis, ""With live-action, it would have turned into a story of people living in a distant land who don't look like us," Satrapi says. "At best, it would have been an exotic story, and at worst, a 'third-world' story" (http://www.awn.com/animationworld/persepolis-motion).

The animation team worked alongside Satrapi to gain a detailed understanding of the types of graphic images she deemed necessary for accuracy. Following her guidelines, the animators, such as interviewee Marc Jousset, commented on their use of "tradition animation techniques" as requested by Satrapi to keep the drawings simple and avoid the "more high-tech techniques" that "would look dated" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). Satrapi's vision, according to Jousset, involved a lot of focus on the characters' physical appearance in terms of sustaining their natural, humane imperfections.

During their initial stages of production, the animation team attempted to use 2D image techniques "on pen tablets," yet were immediately unsatisfied with the product due to the "lack" of "definition," as stated by Jousset (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). Applying traditional techniques as simple as "paper and ink" to the film's production allowed Satrapi to use methods she was familiar with. As a result, Satrapi crafted an image depiction she, herself, would recognize as her own work, and thus, her own story, "It was clear that a traditional animation technique was perfectly suited to Marjane's and Vincent's idea of the film" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf).

Choosing black and white as the dominant colors displayed throughout the film was an intentional choice by Satrapi, along with the director and animation team, to continue on the path of traditional animation techniques. Despite its simplicity in their frequent utilization of only two colors, members of the animation team, such as Jousset, discussed how black and white makes imperfections far more obvious, "Using only black and white in an animation movie requires a great deal of discipline. From a technical point of view, you can't make any mistakes...it shows up straight away on the large screen" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). In addition to color display, the animation team worked especially hard in their artistry techniques that greatly mimicked the styles of Japanese cartoonists, known as "manga," and translated such into their own craft of "a specific style, both realistic and mature. No bluffing, no tricks, nothing overcooked" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). Ultimately, as demonstrated by Jousset, "Marjane had quite an unusual way of working...Marjane insisted on being filmed playing out all the scenes...it was a great source of information for the animators, giving them an accurate approach to how they should work" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). With this in mind, the animators commented on the immense hardships they faced when creating each image of "1,200 shots" through Satrapi's perspective because even though "Marjane's drawings looked very simple and graphic...they're very difficult to work on because there are so few identifying marks. Realistic drawings require outstanding accuracy" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). Despite the difficulties in working with animation film, however, Satrapi's drive and determination towards the making of this film elevated each animators' will to finish each graphic image with full accuracy. Following alongside a more traditional style of graphic imagery was not only difficult in terms of drawing, but also in terms of locating a team to draw the images since traditional animators "hardly exist in France anymore" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). With a group greater than 100 people in number, though, animator Pascal Chevé confirmed the variety of style each team member brought to the table, "An animator will be more focused on trying to make the character move in the right way. Assistant animators will then put the final touches to the drawings to make sure they're true to the original. Then the 'trace' team comes in, and they work on each drawing with...a felt pen, to ensure that they are consistent with the line that runs throughout the movie" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf).

Although it was hard to craft realistic cartoon drawings, Jousset claimed that the dominating challenge was staying "on schedule" and "within budget" of "6 million Euros, which is reasonable for a 2D movie made in France" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf). The two hardest tasks, though, were not as difficult with such a hardworking team that held the ambition to serve justice to Marjane's story, "I think the culmination of the fact that it was a true story, that the main character worked with you, that an animated movie dealt with a current issue and that it was intended for adults was tremendously exciting for the team" (http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/persepolis-interview.pdf).

Reception

Critical response

The film was critically acclaimed. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a 96% approval rating with an average rating of 8.1/10, based on 153 reviews.[6] Metacritic reported the film had an average score of 90 out of 100, based on 31 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[7]

Time magazine's Richard Corliss named the film one of the Top 10 Movies of 2007, ranking it at #6. Corliss praised the film, calling it “a coming-of-age tale that manages to be both harrowing and exuberant.”[8]

It has been ranked No. 58 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[9]

International government reaction

The film has drawn complaints from the Iranian government. Even before its debut at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival, the government-connected organization Iran Farabi Foundation sent a letter to the French embassy in Tehran stating, "This year the Cannes Film Festival, in an unconventional and unsuitable act, has chosen a movie about Iran that has presented an unrealistic face of the achievements and results of the glorious Islamic Revolution in some of its parts."[10] Despite such objections, the Iranian cultural authorities relented in February 2008 and allowed limited screenings of the film in Tehran, albeit with six scenes censored due to sexual content.[11]

In June 2007 in Thailand, the film was dropped from the lineup of the Bangkok International Film Festival. Festival director Chattan Kunjara na Ayudhya stated, "I was invited by the Iranian embassy to discuss the matter and we both came to mutual agreement that it would be beneficial to both countries if the film was not shown" and "It is a good movie in artistic terms, but we have to consider other issues that might arise here."[12]

Persepolis was initially banned in Lebanon after some clerics found it to be "offensive to Iran and Islam." The ban was later revoked after an outcry in Lebanese intellectual and political circles.[13]

Screening controversies

On 7 October 2011, the film was shown on the Tunisian private television station Nessma. A day later a demonstration formed and marched on the station. The main Islamic party in Tunisia, Ennahda, condemned the demonstration.[14] Nabil Karoui, the owner of Nessma TV, faced trial in Tunis on charges of "violating sacred values" and "disturbing the public order." He was found guilty and ordered to pay a fine of 2,400 dinars ($1,700; £1,000), a much more lenient punishment than predicted.[15] Amnesty International said that criminal proceedings against Karoui are an affront to freedom of expression.[16]

In the United States, a group of parents from the Northshore School District, Washington, objected to adult content in the film and graphic novel, and lobbied to discontinue it as part of the curriculum. The Curriculum Materials Adoption Committee felt that "other educational goals—such as that children should not be sheltered from what the board and staff called 'disturbing' themes and content—outweighed the crudeness and parental prerogative."[17]

Awards

- Nominated: Best Animated Feature.[2] Additionally, it is the first traditionally animated nominee since 2005's Howl's Moving Castle. It was also France's Best Foreign Language Film entry, but was not nominated.

- Nominated: Best Foreign Language Film

- Nominated: Best Animated Feature

- Nominated: Directing in an Animated Feature Production

- Nominated: Music in an Animated Feature Production

- Nominated: Writing in an Animated Feature Production

- Won: Best First Work (Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi)

- Won: Best Writing – Adaptation (Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi)

- Nominated: Best Editing (Stéphane Roche)

- Nominated: Best Film

- Nominated: Best Music Written for a Film (Olivier Bernet)

- Nominated: Best Sound (Samy Bardet, Eric Chevallier and Thierry Lebon)

- Tied: Jury Prize

- Nominated: Palme d'Or

- Nominated: Best Picture

- 3rd Globes de Cristal Award

- Won: Best Film

- 2007 London Film Festival

- Southerland Trophy (Grand prize of the festival)

- Special Jury Prize

- Won: Best Foreign Language Film

- Won: Rogers People's Choice Award for Most Popular International Film

- 2009 Silver Condor Awards

See also

References

- ↑ "Persepolis (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. 21 January 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- 1 2 Persepolis at the Big Cartoon DataBase

- 1 2 "Festival de Cannes: Persepolis". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ↑ "List of Cannes Film Festival winners". Associated Press. 2007-05-27. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ↑ Persepolis on the official site of the Cannes Film Festival

- ↑ "Persepolis (2007)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "Persepolis (2007): Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (24 December 2007). "The 10 Best Movies". Time: 40.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema | 58. Persepolis". Empire.

- ↑ "Iran protests screening of movie at Cannes Film Festival". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 20 May 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ↑ "Rare Iran screening for controversial film 'Persepolis'". Agence France-Presse. 2008-02-14.

- ↑ "Thailand pulls Iranian cartoon from film festival". Reuters. 2007-06-27.

- ↑ "LEBANON: Iran revolution film 'Persepolis' unbanned". Los Angeles Times. 28 March 2008.

- ↑ "Protesters attack TV station over film Persepolis". BBC News. 9 October 2011.

- ↑ "Tunisia fines TV channel owner over controversial film". BBC News. 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Minovitz, Ethan (23 January 2012). "Tunisia urged to drop charges over 'Persepolis'". Big Cartoon News. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ↑ Woodinville Weekly "Persepolis"

- Further reading

- Hohenadel, Kristin (21 January 2007). "An Animated Adventure, Drawn From Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Thompson, N. P. (26 January 2008). "Iranian life in cartoon motion". Northwest Asian Weekly. Seattle. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Satrapi, Marjane (February 2008). "Marjane Satrapi". ION Magazine (Interview). Interview with Michael Mann. Vancouver: ION Publishing. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- DePaul, Amy (5 February 2008). "Man with a Country: Amy DePaul interviews Seyed Mohammad Marandi". Guernica. New York. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Persepolis (film). |

- Official website

- Official website (Requires Adobe Flash Player)

- Persepolis at the Internet Movie Database

- Persepolis at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- Persepolis at Box Office Mojo

- Persepolis at Metacritic

- Persepolis at Rotten Tomatoes

- Persepolis at Film Education