Green-veined white

| Green-veined white | |

|---|---|

| | |

| | |

| Both images from Wytham Woods, Oxfordshire, England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Pieridae |

| Genus: | Pieris |

| Species: | P. napi |

| Binomial name | |

| Pieris napi (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

The green-veined white (Pieris napi) is a butterfly of the family Pieridae.

Appearance and distribution

A circumboreal species widespread across Europe and Asia, including the Indian subcontinent, Japan, the Maghreb and North America. (Many authors consider the mustard white of North America to be conspecific with P. napi[1] or consider P. napi to be a superspecies.) It is found in meadows, hedgerows and woodland glades but not as often in gardens and parks like its close relatives the large and small whites, for which it is often mistaken. Like other "white" butterflies, the sexes differ. The female has two spots on each forewing, the male only one. The veins on the wings of the female are usually more heavily marked. The underside hindwings are pale yellow with the veins highlighted by black scales giving a greenish tint, hence green-veined white. Unlike the large and small whites, it rarely chooses garden cabbages to lay its eggs on, preferring wild crucifers. Males emit a sex pheromone that is perceptible to humans, citral,[2] the basic flavor-imparting component of lemon peel oil.[3]

Life cycle and food plants

The eggs are laid singly on a wide range of food plants including hedge mustard (Sisybrium officinale), garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), cuckooflower (Cardamine pratense), water-cress (Rorippa nastutium-aquaticum), charlock (Sinapis arvensis), large bitter-cress (Cardamine amara), wild cabbage (Brassica oleracea), and wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum), and so it is rarely a pest in gardens or field crops. The caterpillar is green and well camouflaged. When full grown it is green above with black warts, from which arise whitish and blackish hairs. There is a darker line along the back and a yellow line low down on the sides. Underneath the colour is whitish-grey. The spiracular line is dusky but not conspicuous, and the spiracles are blackish surrounded with yellow. There is extensive overlap with other leaf-feeding larvae of large and small whites in some wild populations (e.g. in Morocco). It is often found feeding on the same plant as the orange tip but rarely competes for food because it usually feeds on the leaves whereas the orange tip caterpillar feeds on the flowers and developing seed pods. Like other Pieris species it overwinters as a pupa. This is green in colour, and the raised parts are yellowish and brown. This is the most frequent form, but it varies through yellowish to buff or greyish, and is sometimes without markings.

Habitat

P. napi is found in damp, grassy places with some shade, forest edges, hedgerows, meadows and wooded river valleys. The later generations widen their habitat use in the search for alternative food plants in drier, but flowery places. In the Mediterranean the insect is also found in scrub around mountain streams or springs and on floodplains with Nasturtium officinale. It is found from sea level to high elevations (2500 m in central Europe, 2600 m in Italy, 3600 m in Morocco).

Flight times

The generations vary with location, elevation and season. In northern Europe there are two or three generations from April to early September. In warmer areas and in some good years there is a fourth generation. In southern Europe there are three or more partially overlapping generations from March to October.

Seasonal variation

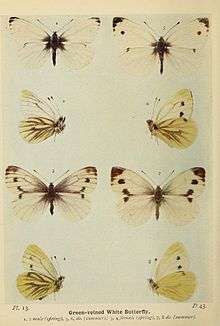

In Great Britain, April, May and June specimens have the veins tinged with grey and rather distinct, but are not so strongly marked with black as those belonging to the second flight, which occurs in late July and throughout August. This seasonal variation, as it is called, is also most clearly exhibited on the underside. In the May and June butterfly (plate 13, left side) the veins below are greenish grey, and those of the hindwings are broadly bordered also with this colour. In the bulk of the July and August specimens (plate 13, right side) only the nervures are shaded with greenish grey, and the nervures are only faintly, or not at all, marked with this colour. Now and then a specimen of the first brood may assume the characters properly belonging to the specimens of the second brood; and, on the other hand, a butterfly of the second brood may closely resemble one of the first brood. As a rule, however, the seasonal differences referred to are fairly constant. By rearing this species from the egg it has been ascertained that part (sometimes the smaller) of a brood from eggs laid in June attains the butterfly stage the same year, and the other part remains in the chrysalis until the following spring, the butterflies in each set being of the form proper to the time of emergence.

Behaviour

Senses

Recent research has shown that when males mate with a female, they inject methyl salicylate along with their sperm. The smell of this compound repels other males, thus ensuring the first male's paternity of the eggs—a form of chemical mate guarding.[4]

After a female mates, she will display a mate refusal posture that releases methyl salicylate during a subsequent courtship. The release of this anti-aphrodisiac will quickly terminate the courtship. Males are very sensitive to differences in methyl salicylate levels, and will use this sense to influence their mating behaviour. However, a virgin female displaying a very similar posture will release a different chemical that will prolong the courtship ritual. Males are sensitive to these chemical and postural differences, and can discriminate between a receptive virgin female and an unreceptive mated female.[5]

The adult male of this species has a distinctive odour that resembles lemon verbena.[6] This smell is associated with specialized androconial scales on male wings.

Mating system

In the usually polyandrous P. napi, females who mate multiple times have higher lifetime fecundity, lay larger eggs, and live longer compared to females who mate only once.[7] In most organisms it is the female who contributes the most to the reproduction of offspring as she must invest an egg and then carry the zygote. Males, on the other hand, need only provide a sperm that is of low cost. In P. napi, however, mating is unusually costly to males as the ejaculate matter produced contains not only sperm but accessory substances as well. These substances average 15% of male body mass and are incorporated into female soma and reproductive tissues during the mating process.[7] Therefore, the nuptial gift given by P. napi males qualifies both as paternal investment and mating effort. This system is unlike other types of butterflies such as Pararge aegeria, where female reproductive effort is independent of male ejaculate.[8]

The amount of ejaculate of virgin males during mating is larger than that of non-virgin males. Females therefore must mate more frequently with non-virgin males in order to obtain the necessary amount of male-derived nutrition.

Sexual cooperation and conflict

In P. napi, the nuptial gift is an example of sexual cooperation towards a common interest of both males and females. The existence of nutrients in the ejaculate is beneficial to the females because it increases female fecundity and longevity, and eventually promotes re-mating. The existence of the anti-aphrodisiac, methyl salicylate, is effective in reducing female harassment by other males.[9]

However, the transfer of this ejaculate can cause a conflict over re-mating due to sperm competition. After a female mates, infertile sperm ejaculated by the male will fill the female's sperm storage organ and prevent her from mating. The amount of infertile sperm stored is correlated with the refractory period of a female after mating. Infertile sperm makes up 90% of the sperm count, showing that males manipulate females by preventing them from mating with another male for a certain period of time. Although polyandry benefits females of P. napi by maximizing the amount of transferred nutrients from the male, the infertile sperm storage prolongs female re-mating.[10]

This refractory period makes it harder for females to mate, and females will continue to have difficulty as their age and mating frequency increase. Males who have recently copulated will not transfer as many nutrients to their next mate, but will spend a longer duration of time for each mating. This increases the mating costs for females because they are spending more time copulating and receiving fewer nutrients from the ejaculate. Males take advantage of this because females do not reduce their mating costs by copulating with virgin males.[11] In addition, males will transfer the most methyl salicylate to their first mate to ensure its paternity. However, a female who mates with a virgin male will have the most difficulty re-mating, therefore delaying her from engaging in the preferred polyandry. Males tailor their ejaculate in the sense that the first ejaculate is meant to prolong the refractory period of the female, and every subsequent ejaculate is meant to maximize efficiency in sperm competition.[5]

Size difference and mating frequency

Smaller females may be able to compensate for their size by receiving male ejaculate through increased mating frequency. However, this is not the case, as larger females are more polyandrous. Larger females are able to break down the spermatophore and reduce the refractory period to increase mating frequency.[12]

Taxonomy

Some authorities consider P. napi to be a superspecies including the West Virginia white butterfly, the mustard white and the dark-veined white.

Similar species

- Pieris bryoniae

- Pieris ergane

- Pieris krueperi – Krueper's small white

- Pieris rapae – small white

Subspecies

_female.jpg)

Portugal

- Pieris napi adalwinda (Fruhstorfer, 1909) Finland, Sweden

- Pieris napi meridionalis Heyne & Rühl, 1895 Spain, Italy

- Pieris napi segonzaci (le Cerf, 1923) High Atlas

- Pieris napi maura (Verity, 1911) Glacières de Blida, Algeria

- Pieris napi atlantis (Oberthür, 1923) Azrou, Middle Atlas, Morocco

- Pieris napi flavescens (Wagner, 1903) Mödling, Austria

- Pieris napi lusitanica Lep. Portug. Porto: 2, 1929 De Sousa Portugal

For others see Wikispecies.

Synonyms

- Pieris adalwinda Fruhstorfer, 1909[13]

- Pieris arctica Verity, 1911[13]

- Pieris canidiaformis Drenowsky, 1910[13]

- Pieris dubiosa Röber, 1907[13]

- Pieris flavescens Wagner, 1903[13]

- Pieris meridionalis Heyne, 1895[13]

See also

- Dark-veined white

- Mustard white

- List of butterflies of India (Pieridae)

- List of butterflies of Great Britain

- Species problem

References

- ↑ Howe, William H. The Butterflies of North America (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1975)

- ↑ Andersson, J.; Borg-Karlson, A. -K.; Vongvanich, N.; Wiklund, C. (2007). "Male sex pheromone release and female mate choice in a butterfly". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (6): 964. doi:10.1242/jeb.02726.

- ↑ Maarse, H. (1991). Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages. CRC Press. p. 319. ISBN 0-8247-8390-5.

- ↑ Andersson, Johan, Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson and Christer Wiklund (2003). "Antiaphrodisiacs in pierid butterflies: a theme with variation!". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 29 (6): 1489–99. doi:10.1023/a:1024277823101. PMID 12918930.

- 1 2 Andersson, Johan; Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson, Christer Wiklund; Wiklund, C. (2003). "Sexual conflict and anti-aphrodisiac titre in a polyandrous butterfly: male ejaculate tailoring and absence of female control" (PDF). The Royal Society. 271 (1550): 1765–1770. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2671. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ Gilbert, Avery N. (2008), What the nose knows: the science of scent in everyday life, Random House of Canada, ISBN 978-1-4000-8234-6

- 1 2 Kaitala, Wiklund (1994). "Polyandrous female butterflies forage for matings". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 35: 385–388. doi:10.1007/bf00165840.

- ↑ Wedell, N.; Karlsson, B. (2003). "Paternal investment directly affects female reproductive effort in an insect". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1528): 2065–71. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2479. PMID 14561296.

- ↑ Andersson, Johan; Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson, Christer Wiklund; Wiklund, C (2000). "Sexual cooperation and conflict in butterflies: a male-transferred anti-aphrodisiac reduces harassment of recently mated females" (PDF). The Royal Society. 267 (1450): 1271–1275. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1138. PMC 1690675

. PMID 10972120. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

. PMID 10972120. Retrieved 17 September 2013. - ↑ Wedell, Nina; Christer Wiklund; Jonas Bergstrom (2009). "Coevolution of non-fertile sperm and female receptivity in a butterfly". Biol Letter. 5 (5): 678–6781. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0452. PMC 2781977

. PMID 19640869.

. PMID 19640869. - ↑ Kaitala, Arja; Christer Wiklund (1995). "Female mate choice and mating costs in the polyandrous butterfly Pieris napi (Lepidoptera: Pieridae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 8 (3): 355–363. doi:10.1007/bf01989364. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ Bergstrom, Jonas; Christer Wiklund; Arja Kaitala (2002). "Natural variation in female mating frequency in a polyandrous butterfly: effects of size and age". Animal Behavior. 64: 49–54. doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3032. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Pieris napi (Linnaeus 1758)". Fauna Europaea. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

Further reading

- Asher, Jim et al. The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies of Britain and Ireland Oxford university Press

- Bowden, S. R.; & Riley, Norman Denbigh (1967): The type-material of Pieris napi pseudorapae Verity. Redia 50, pp. [379-380]

- Bowden, S. R. (Aug 68) Pieris napi in Calabria. Entomologist 101, pp. [180-190]

- Bowden, S. R. (Oct 1970) Polymorphism in Pieris: f. sulphurea in Pieris napi marginalis. Entomologist 103, pp. [241-249]

- Bowden, S. R. (1954) Pieris napi L. f. hibernica Schmidt, eine kuenstliche Aberration? Der gegenwaertige Stand der Frage. Mitt. ent. Ges. Basel (nf)4, pp. [9-15, 17-22]

- Bowden, S. R. (1956) Hybrids within the European Pieris napi L. species-group. Proc. Trans. S. Lond. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 1954-55, pp. [135-159]

- Bowden, S. R. (1961) Pieris napi L. ab. sulphurea Schoeyen Entomologist 94, pp. [221-226]

- Bowden, S. R. (1962) Übertragung von Pieris napi-Genen auf Pieris bryoniae durch wiederholte Ruckkreuzung. Z. Arbgem. Öst. Ent. 14, pp.

- Bowden, S. R. (1966a) Polymorphism in Pieris Entomologist 99, pp. [174-182]

- Bowden, S. R. (1966b) 'Irregular' diapause in Pieris, with a note on Corsican Pieris brassicae L. Proc. Trans. S. Lond. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 1966, pp. [67-68]

- Bowden, S. R. (1966c) Pieris napi in Corsica. Entomologist 99, pp. 57–68

- Bowden, S. R. (1970a) What is Pieris dubiosa Warren? Ent. Rec. 82, pp.

- Bowden, S. R. (1970b) Pieris napi L.: speciation and subspeciation. Proc. Trans. Br. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 3, pp. [63-70]

- Bowden, S. R. (1971). "'Pieris napi' in America: reconnaissance. Proc". Trans. Br. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 4: 71–77.

- Bowden, S. R. (1972) 'Pieris napi' in America: genetic imbalance in hybrids. Proc. Trans. Br. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 4, pp. [103-117]

- Bowden, S. R. (1975a) Some subspecific and infrasubspecific names in Pieris napi L. Ent. Rec. 87, pp. [153-156]

- Bowden, S. R. (1975b) Relation of Pieris melete Menetries to Pieris napi L.: ssp. melete. Proc. Trans. Br. ent. nat. Hist. Soc. 7, pp. [97-102]

- Bowden, S. R. (1979) Subspecific Variation in Butterflies: Adaptation and Dissected Polymorphism in Pieris (Artogeia) (Pieridae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 33(2), pp. [77-111, 40 f

- Bowden, S. R. (): Sexual mosaics in Pieris. Lep. News 12(1-2), pp. [7-13, 1 tbl, 1 f]

- Bowden, S. R. (): Pieris napi L. (Pieridae) and the Superspecies Concept. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 26(3), pp. 170–173

- Bowden, S. R. (1985): Taxonomy for a variable butterfly? [Pieris napi]. Ent. Gaz. 36(2), pp. [85-90]

- Carter, David, 1993 Farfalle e falene Fabbri Editori

- Chew, F.S and Watt, W.B 2006 The green-veined white (Pieris napiL.), its Pierine relatives, and the systematics dilemmas of divergent character sets (Lepidoptera, Pieridae)Biological Journal of the Linnean Society2006, 413–435.

- Chinery, Michael, 1987 Guida degli insetti d'Europa Franco Muzzio Editore

- Chinery, Michael, 1989 Farfalle d'Italia e d'Europa De Agostini/Collins

- Chou Io (Ed.) Monographia Rhopalocerum Sinensium, 1-2

- Dyar, 1903 A List of North American Lepidoptera and Key to the Literature of this Order of Insects Bull. U.S. natn. Mus., 52: xix, 723pp

- Edwards (1869). "Descriptions of new species of diurnal Lepidoptera found within the United States". Trans. amer. ent. Soc. 2: 369–376. doi:10.2307/25076222.

- Eitschberger, 1983 Eitschberger, 1984; Systematische Untersuchungen am Pieris napi-bryoniae-Komplex (s.l.) Herbipoliana 1 (1-2): (1) i-xxii, 1-504, (2) 1-601

- Eitschberger (2001). "Eine neue Unterart von Pieris napi (Linnaeus, 1758) vom Polar Ural". Atalanta. 32 (1/2): 85–88.

- Fruhstorfer, 1909 Neue palaearktische Pieriden Int. ent. Zs. 3 (16): 88 (17 July)

- Hensle, 2001 Zur Frage der subspezifischen Zuordnung von Pieris bryoniae lappona Rangnow, 1935 Atalanta 32 (1/2): 89-95

- Hodges, Ronald W. (ed.), 1983 Check List of the Lepidoptera of America North of Mexico

- Korshunov, Y.P. and Gorbunov, P.Y., 1995 The Butterflies (Rhopalocera) of the Asian part of Russia'Pensoft Digital version in English

- Lamas Gerardo, 2004 Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera; Checklist: Part 4A; Hesperioidea Papilionoidea

- Leraut, Patrice, 1992 Le farfalle nei loro ambienti Ed. A. Vallardi (ecoguide)

- Linnaeus, 1758 Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Symonymis, Locis. Tomis I. 10th Edition Syst. Nat. (Edn 10) 1

- Lorkovic, Zdravko (1968). "Karyologischer Beitrag zur Frage der Fortpflanzungs verhaltnisse Sudeuropäischer Taxone von Pieris napi (L.). (Lep. Pieridae)". Biol. Glasn. 21: 95–136.

- Mazzei Paolo, Reggianti Diego and Pimpinelli Ilaria Moths and Butterflies of Europe

- Pyle, R. M. National Audubon Society: Field Guide to North American Butterflie1981; ISBN 0-394-51914-0

- Scott, J. A. 1986 The butterflies of North America: a natural history and field guide. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California

- Seppänen, E. J, 1970 Suomen suurperhostoukkien ravintokasvit, Animalia Fennica 14

- Tennent, John, 1996 The butterflies of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia; ISBN 0-906802-05-9

- Tuzov, Bogdanov, Devyatkin, Kaabak, Korolev, Murzin, Samodurov, Tarasov, 1997 Guide to the Butterflies of Russia and adjacent territories; Hesperiidae, Papilionidae, Pieridae, Satyridae; Volume 1

- Verity, 1908; Verity, [1909]; Verity, 1911; Rhopalocera Palaearctica Iconographie et Description des Papillons diurnes de la région paléarctique. Papilionidae et Pieridae Rhopalocera Palaearctica 1: 86+368pp, 2+12+72pls

- Wynter-Blyth, M. A., 1957 Butterflies of the Indian Region; (1982 Reprint)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rapsweißling. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Pieris napi |

- Pieridae Holarctinae Photos of imagos and la

- www.schmetterling-raupe.de

- Mario Meier - Europäische Schmetterlinge

- www.eurobutterflies.com

- Moths and Butterflies of Europe and North Africa

- Naturkundliches Informationssystem: Pieris napi napi (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Naturkundliches Informationssystem: Pieris napi flavescens F.Wagner, 1903