Portuguese Timor

| Portuguese Timor | ||||||||||||

| Timor Português | ||||||||||||

| Colony of the Portuguese Empire | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

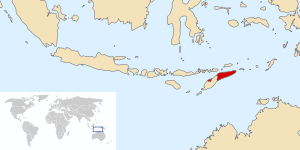

Portuguese Timor with 1869-established boundaries. | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Lifau (1702-1769) Dili (1769-1975) | |||||||||||

| Languages | Tetum, Portuguese, Malay | |||||||||||

| Government | Colony | |||||||||||

| Head of state | ||||||||||||

| • | Monarch 1515–1521 |

Manuel I (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 1908-1910 | Manuel II (Last) | ||||||||||

| • | President 1910-1911 |

Teófilo Braga (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 1974-1975 | Francisco da Costa Gomes (Last) | ||||||||||

| Governor | ||||||||||||

| • | 1702–1705 | António Coelho Guerreiro (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 1974–1975 | Mário Lemos Pires (Last) | ||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

| • | Colonisation | 1702 | ||||||||||

| • | Invasion by Indonesia | 7 December 1975 | ||||||||||

| • | Independence of East Timor | 20 May 2002 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Timorese pataca (PTP) Timorese escudo (PTE) | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of East Timor |

|

| Chronology |

| Topics |

|

|

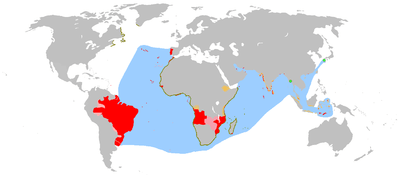

Portuguese Timor was the name of East Timor when it was under Portuguese control. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

The first Europeans to arrive in the region were the Portuguese in 1515.[1] Dominican friars established a presence on the island in 1556, and the territory was declared a Portuguese colony in 1702. Following a Lisbon-instigated decolonisation process, Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975. However, the invasion and susequent annexation was not recognised by other countries, so Portuguese Timor existed officially up until independence in 2002.

Early colonialists

Prior to the arrival of European colonial powers, the island of Timor was part of the trading networks that stretched between India and China and incorporating Maritime Southeast Asia. The island's large stands of fragrant sandalwood were its main commodity.[2] The first European powers to arrive in the area were the Portuguese in the early sixteenth century followed by the Dutch in the late sixteenth century. Both came in search of the fabled Spice Islands of Maluku. In 1515, Portuguese first landed near modern Pante Macassar. Portuguese merchants exported sandalwood from the island, until the tree nearly became extinct.[1] In 1556 a group of Dominican friars established the village of Lifau.

In 1613, the Dutch take control of the Western part of the island.[1] Over the following three centuries, the Dutch would come to dominate the Indonesian archipelago with the exception of the eastern half of Timor, which would become Portuguese Timor.[2] The Portuguese introduced maize as a food crop and coffee as an export crop. Timorese systems of tax and labour control were preserved, through which taxes were paid through their labour and a portion of the coffee and sandalwood crop. The Portuguese introduced mercenaries into Timor communities and Timor chiefs hired Portuguese soldiers for wars against neighbouring tribes. With the use of the Portuguese musket, Timorese men became deer hunters and suppliers of deer horn and hide for export.[3]

The Portuguese introduced Roman Catholicism to East Timor, the Latin writing system, the printing press, and formal schooling.[3] Two groups of people were introduced to East Timor: Portuguese men, and Topasses. Portuguese language was introduced into church and state business, and Portuguese Asians used Malay in addition to Portuguese.[3] Under colonial policy, Portuguese citizenship was available to men who assimilated Portuguese language, literacy, and religion; by 1970, 1,200 East Timorese, largely drawn from the aristocracy, Dili residents, or larger towns, had obtained Portuguese citizenship. By the end of the colonial administration in 1974, 30 percent of Timorese were practising Roman Catholics while the majority continued to worship spirits of the land and sky.[3]

Establishment of the colonial state

In 1702, Lisbon sent its first governor successfully, António Coelho Guerreiro,[4] to Lifau, which became capital of all Portuguese dependencies on Lesser Sunda Islands. Former capitals were Solor and Larantuka. Portuguese control over the territory was tenuous particularly in the mountainous interior. Dominican friars, the occasional Dutch raid, and the Timorese themselves competed with Portuguese merchants. The control of colonial administrators was largely restricted to the Dili area, and they had to rely on traditional tribal chieftains for control and influence.[2]

The capital was moved to Dili in 1769, due to attacks from the Topasses, who became rulers of several local kingdoms (Liurai). At the same time, the Dutch were colonising the west of the island and the surrounding archipelago that is now Indonesia. The border between Portuguese Timor and the Dutch East Indies was formally decided in 1859 with the Treaty of Lisbon. In 1913, the Portuguese and Dutch formally agreed to split the island between them.[5] The definitive border was drawn by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1916, and it remains the international boundary between the modern states of East Timor and Indonesia.

For the Portuguese, East Timor remained little more than a neglected trading post until the late nineteenth century. Investment in infrastructure, health, and education was minimal. Sandalwood remained the main export crop with coffee exports becoming significant in the mid-nineteenth century. In places where Portuguese rule was asserted, it tended to be brutal and exploitative.[2]

Twentieth century

_Avos_Ceres.jpg)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a faltering home economy prompted the Portuguese to extract greater wealth from its colonies, resulting in increased resistance to Portuguese rule in East Timor. In 1910–12, a Timorese rebellion was quashed after Portugal brought in troops from its colonies in Mozambique and Macau, resulting in the deaths of 3,000 East Timorese.[5]

In the 1930s, the Japanese semi-governmental Nan’yō Kōhatsu development company, with the secret sponsorship of the Imperial Japanese Navy invested heavily in a joint-venture with the primary plantation company of Portuguese Timor, SAPT. The joint-venture effectively controlled imports and exports into the island by the mid-1930s and the extension of Japanese interests greatly concerned the British, Dutch and Australian authorities.[7]

Although Portugal was neutral during World War II, in December 1941, Portuguese Timor was occupied by a small British, Australian and Dutch force, to preempt a Japanese invasion. However, the Japanese did invade in the Battle of Timor in February 1942. Under Japanese occupation, the borders of the Dutch and Portuguese were overlooked with Timor island being made a single Japanese army administration zone.[3] 400 Australian and Dutch commandos trapped on the island by the Japanese invasion waged a guerrilla campaign, which tied up Japanese troops and inflicted over 1,000 casualties.[5] Timorese and the Portuguese helped the guerillas but following the Allies' eventual evacuation, Japanese retribution from their soldiers and Timorese militia raised in West Timor was severe.[3] By the end of the War, an estimated 40–60,000 Timorese had died, the economy was in ruins, and famine widespread.[5][8] (see Battle of Timor).

Following World War II, the Portuguese promptly returned to reclaim their colony, while West Timor became part of Indonesia, which secured its independence in 1949. To rebuild the economy, colonial administrators forced local chiefs to supply labourers which further damaged the agricultural sector.[5] The role of the Catholic Church in East Timor grew following the Portuguese government handing over the education of the Timorese to the Church in 1941. In post-war Portuguese Timor, primary and secondary school education levels significantly increased, albeit on a very low base. Although illiteracy in 1973 was estimated at 93 per cent of the population, the small educated elite of East Timorese produced by the Church in the 1960s and 1970s, became the independence leaders during the Indonesian occupation.[5]

End of Portuguese rule

Following a 1974 coup (the "Carnation Revolution"), the new government of Portugal favoured a gradual decolonisation process for Portuguese territories in Asia and Africa. When East Timorese political parties were first legalised in April 1974, three major players emerged. The Timorese Democratic Union (UDT), was dedicated to preserving East Timor as a protectorate of Portugal and in September announced its support for independence.[9] Fretilin endorsed "the universal doctrines of socialism", as well as "the right to independence",[10] and later declared itself "the only legitimate representative of the people".[11] A third party, APODETI emerged advocating East Timor's integration with Indonesia[12] expressing concerns that an independent East Timor would be economically weak and vulnerable.[13]

On 28 November 1975, Fretilin unilaterally declared the territory's independence.

Nine days later, Indonesia invaded the territory declaring it Indonesia's 27th province Timor Timur in 1976. The United Nations, however, did not recognise the annexation. The last governor of Portuguese Timor was Mário Lemos Pires from 1974–75. Following the end of Indonesian occupation in 1999, and a United Nations administered transition period, East Timor became formally independent in 2002.

The first Timorese currency was the Portuguese Timor pataca (introduced 1894), and after 1959 the Portuguese Timor escudo, linked to the Portuguese escudo, was used. In 1975 the currency ceased to exist as East Timor was annexed by Indonesia and began using the Indonesian rupiah.

See also

References

- Dunn, James (1996). Timor: A People Betrayed. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ISBN 0-7333-0537-7.

- Goto, Kenichi. "Japan and Portuguese Timor in the 1930s and early 1940s" (PDF).

- Indonesia. Department of Foreign Affairs. Decolonization in East Timor. Jakarta: Department of Information, Republic of Indonesia, 1977. OCLC 4458152.

- Schwarz, A. (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Westview Press. ISBN 1-86373-635-2.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 0-8160-7109-8.

Notes

- 1 2 3 West, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwartz (1994), p. 198

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor (2003), p. 379.

- ↑ History of Timor

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schwartz (1994), p. 199.

- ↑ Flags of the World

- ↑ Post, The Encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War , pages 560-561;

- ↑ Goto.

- ↑ Dunn (1996), p. 53–54.

- ↑ Quoted in Dunn, p. 56.

- ↑ Quoted in Dunn, p. 60.

- ↑ Dunn, p. 62; Indonesia (1977), p. 19.

- ↑ Dunn, p. 62.

External links

- History of Timor – Technical University of Lisbon

- Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea; Conflict and Adaptation in Early Colonial Timor, 1600–1800 – KITLV Press 2012. Open Access

Coordinates: 8°33′00″S 125°35′00″E / 8.5500°S 125.5833°E