Prince's Palace of Monaco

The Prince's Palace of Monaco is the official residence of the Prince of Monaco. Built in 1191 as a Genoese fortress, during its long and often dramatic history it has been bombarded and besieged by many foreign powers. Since the end of the 13th century, it has been the stronghold and home of the Grimaldi family who first captured it in 1297. The Grimaldi ruled the area first as feudal lords, and from the 17th century as sovereign princes, but their power was often derived from fragile agreements with their larger and stronger neighbours.

Thus while other European sovereigns were building luxurious, modern Renaissance and Baroque palaces, politics and common sense demanded that the palace of the Monegasque rulers be fortified. This unique requirement, at such a late stage in history, has made the palace at Monaco one of the most unusual in Europe. Indeed, when its fortifications were finally relaxed during the late 18th century, it was seized by the French and stripped of its treasures, and fell into decline, while the Grimaldi were exiled for over 20 years.

The Grimaldi's occupation of their palace is also unusual because, unlike other European ruling families, the absence of alternative palaces and land shortages have resulted in their use of the same residence for more than seven centuries. Thus, their fortunes and politics are directly reflected in the evolution of the palace. Whereas the Romanovs, Bourbons, and Habsburgs could, and frequently did, build completely new palaces, the most the Grimaldi could achieve when enjoying good fortune, or desirous of change, was to build a new tower or wing, or, as they did more frequently, rebuild an existing part of the palace. Thus, the Prince's Palace reflects the history not only of Monaco, but of the family which in 1997 celebrated 700 years of rule from the same palace.[1]

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the palace and its owners became symbols of the slightly risqué glamour and decadence that were associated with Monte Carlo and the French Riviera. Glamour and theatricality became reality when the American film star Grace Kelly became chatelaine of the palace in 1956. In the 21st century, the palace remains the residence of the current Prince of Monaco.

Princely Palace

The palace is a blend of architectural styles; its ancient origins are indicated by a lack of symmetry. Thus to evaluate the architecture, wings and blocks have to be observed separately. The principal façade appears as a terrace of Renaissance style palazzi from differing periods of the Renaissance era (Illustrations 1 and 12) which—even though they form only one palace—is exactly what they are. These wings are however united by their common rusticated ground floor. This Renaissance architecture seems to mask earlier fortifications, the towers of which rise behind the differing classical façades. These towers—many complete with crenellations and machicolations—were actually mostly rebuilt during the 19th century. At the rear of the palace the original medieval fortifications seem untouched by time. (Illustration 4). A greater architectural harmony has been achieved within the court of honour around which the palace is built, where two tiers of frescoed open arcades serve as both a ceremonial balcony for the prince's appearances and a state entrance and corridor linking the formal state rooms of the palace.

The most notable of the many rooms are the state apartments. These were laid out from the 16th century onwards, and were enhanced in the style of those at Versailles during the 18th century. In the 19th century and again during the late 20th century, large-scale restoration of the state rooms consolidated the 18th-century style which prevails today.

Designed as an enfilade and a ceremonial route to the throne room, the processional route begins with an external horseshoe-shaped staircase which leads from the court of honour to the open gallery known as the Gallery of Hercules. From here guests enter the Mirror Gallery, a long hall inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.[2] This gallery leads to the first of the state rooms, the Officer's Room, where guests are greeted by court officials before an audience with the prince in the Throne Room. From the Officer's Hall the enfilade continues to the Blue Room. This large drawing room, decorated with blue brocade, is hung with Grimaldi family portraits and has chandeliers of Murano glass. The following room, the largest of the state apartments, is the Throne Room. Its ceiling and frescoes were executed by Orazio de Ferrari and depict the surrender of Alexander the Great. The throne, in the Empire style, is positioned on a dais, beneath a red silk canopy of estate surmounted by a gilt crown. The floors are of Carrara marble. All state ceremonies have been held in this room since the 16th century.[3]

Other rooms in the state suite include the Red Room — so called because its walls are covered in red brocade — a large drawing room containing paintings by Jan Brueghel and Charles Le Brun. Like much of the palace the room contains ornate 18th-century French-style furniture. From the Red Room leads the York Room. Furnished as a state bedchamber, this room is frescoed with illustrations of the four seasons by Gregorio de Ferrari. The following room, known as the Yellow Room (or sometimes as the Louis XV Bedchamber), is another state bedroom.

The most remarkable room in the suite is the Mazarin Room. This drawing room is lined with Italian gilded and painted polychrome boiseries by craftsmen brought to France by Cardinal Mazarin, who was related by marriage to the Grimaldi. Cardinal Mazarin's portrait hangs above the fireplace.

While the overriding atmosphere of the interior and exterior of the palace is of the 18th century, the palace itself is not. Much of its appearance is a result of a long evolution dating from the 12th century, overshadowed by heavy restoration and refurnishing during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Grimaldi fortress

Monaco's history predates the Roman occupation of AD 122. Its large natural harbour ensured a steady stream of visitors from Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon. Later the Phoenicians came to trade silk, oil, and spices with the natives. It was the Phoenicians who introduced to this area of the Mediterranean their god Melkart, later known by the Romans as Hercules Monoikos. It was after this god that the Romans renamed the area Portus Hercules Moneici, which has evolved to the present name of Monaco.[4] The seat of the Prince of Monaco was established on the Rocher de Monaco (Illustration 5) as a fortress in 1191 when the harbour, that is today lined by Monte Carlo, was acquired by the Republic of Genoa. The harbour and its immediate area were given to the Genoese by the Emperor Henry IV with the proviso that the Genoese protect the coastline from piracy. Further territory was ceded to the new owners by the Council of Peille and the Abbaye de Saint Pons. In 1215 work began on a new fortress, comprising four towers connected by ramparts protected by a curtain wall. This forms the core of the present palace.

Genoa was important in the politics of 12th-century Europe. The Genoese were a nation of merchants, and such was their wealth that they frequently fulfilled a role as bankers to the other nation states. However, the Genoese became divided following the rift caused when the Emperor Frederick II challenged the power of Pope Innocent IV. Two distinct camps formed: the Guelphs who supported the pope and the Ghibellines who were loyal to the imperial crown. Siding with the Guelphs were one of the patrician families of Genoa—the Grimaldi. Throughout the 13th century these two groups fought. Finally at the end of the century the Ghibellines were victorious and banished their opponents, including the Grimaldi, from Genoa. The Grimaldi settled in the area today known as the French Riviera. Several castles in the area are still known as Chateau Grimaldi, and testify to the strong presence of various branches of the family in the vicinity.

Legend relates that in January 1297 François Grimaldi, disguised as a monk, sought shelter at the castle. On obtaining entry he murdered the guard, whereupon his men appeared and captured the castle.[5] Thus the fortress became the stronghold of the Grimaldi. This event is commemorated by a statue of François Grimaldi in the precincts of the palace (Illustration 6) and in the arms of the House of Grimaldi where François is depicted wielding a sword while in the garb of a monk (Illustration 2).

Charles I, who ruled from 1331 to 1357, and was the son of François Grimaldi's cousin Rainier I, significantly enlarged the fortress by adding two large buildings: one against the eastern ramparts and the second looking out over the sea. This changed the appearance of the fortress, making it appear more of a fortified house than a fortress.[6] The fortifications remained very necessary, for during the next three decades the fortress was alternately lost and regained by the Grimaldi to the Genoese. In 1341 the Grimaldi took Menton and then Roquebrune, thus consolidating their power and strength in the area. Subsequently they strengthened not only the defences of the harbour but also their fortress on the Rocher. The Grimaldi's stronghold was now a power base from which the family ruled a large but very vulnerable area of land.

For the next hundred years the Grimaldi defended their territory from attacks by other states which included Genoa, Pisa, Venice, Naples, France, Spain, Germany, England and Provence. The fortress was frequently bombarded, damaged, and restored. Gradually the Grimaldi began to make an alliance with France which strengthened their position. Now more secure, the Grimaldi lords of Monaco now began to recognise the need not only to defend their territory, but also to have a home reflecting their power and prestige.

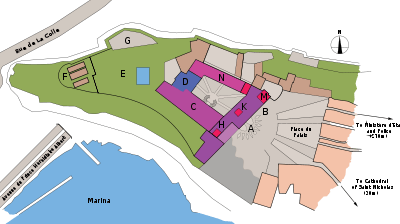

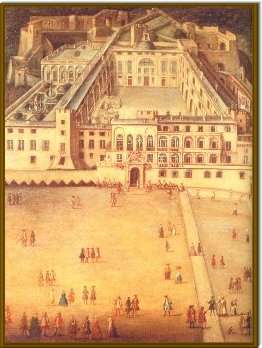

Throughout the 15th century, both the fortress and the Rocher continued to be extended and further defended until it became a garrison accommodating some 400 troops.[2] The slow transformation from fortified house to palace (Illustration 7) began during this era, first with building by Lamberto Grimaldi, Lord of Monaco (who between 1458 and 1494 was "a noteworthy ruler who handled diplomacy and the sword with equal talent"[7]), and then by his son Jean II. This period saw the extension of the east side of the fortress with a three–floored wing, guarded by high scalloped walls connecting the bastion towers—St Mary (M in Illustration 7), Middle (K) and South (H). This large new wing contained the palace's principal room, the State Hall (today known as the Guard Room). Here the princes carried out their official business and held court.[6] Further, more luxurious, rooms complete with balconies and loggias were designed for the private use of the Grimaldi family. In 1505 Jean II was killed by his brother Lucien.[8]

Fortress to palace

Lucien I (1505–1523)

Jean II was succeeded by his brother Lucien I. Peace did not reign in Monaco for long; in December 1506 14,000 Genoese troops besieged Monaco and its castle, and for five months 1,500 Monégasques and mercenaries defended the Rocher before achieving victory in March 1507. This left Lucien I to walk a diplomatic tightrope between France and Spain in order to preserve the fragile independence of the tiny state which was in truth subject to Spain. Lucien immediately set about repairing the ravages of war to the fortified palace which had been damaged by heavy bombardment.[9] To the main wing (see Illustrations 3 & 7 – H to M ), built by Prince Lambert and extended during the reign of Jean II, he now added a large wing (H to C) which today houses the state apartments.

Honoré I (1523–1581)

During the reign of Honoré I the internal transformation from fortress to palace was continued. The Treaty of Trodesillas at the beginning of Honoré's rule clarified Monaco's position as a protectorate of Spain, and thus later of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. This provided the security to allow the Lord of Monaco to concentrate on the more comfortable side of his residence rather than the constant need to defend it.

The courtyard was rebuilt, the architect Dominique Gallo designing two arcades, stretching between points H and C. The arcades, fronting the earlier wing by Lucien I, each have twelve arches, decorated by white marble balustrading on the upper level. Today the upper arcades are known as the Galerie d'Hercule (gallery of Hercules) because their ceilings were painted with scenes depicting the Labours of Hercules by Orazio de Ferrari during the later reign of Honoré II. These arcades or loggias provide corridors to the state rooms in the south wing (today known as the State Rooms Wings). On the other side of the courtyard a new wing was constructed and the Genoese artist Luca Cambiasi was charged with painting its external walls with frescoes. It is thought that the galleries (B) to the north wing overlooking the harbour were built at this time.[9]

Further enlargements were carried out in order to entertain the Emperor Charles V in 1529, when he stayed four nights at the palace during his journey in state to Bologna for his coronation by Pope Clement VII.

Architecturally this was an exciting period, but Honoré I was unable to remodel the fortress in the grand style of a Renaissance palazzo. In spite of the Spanish protection, the risk of attack from France was high and defence remained Honoré's main priority.[9] With this in mind he added two new features: All Saints Tower (F) and the Serravalle Bastion (G). All Saints Tower was semi-circular and guarded the end of the rock promontory. Complete with gun platforms and cannon, it was connected to man-made caves in the rock itself. Subterranean passages also linked it to the Serravalle Bastion, which was in essence a three-storey gun tower bristling with cannon. Underneath the courtyard a cistern was installed, providing sufficient water for 1000 troops for a 20-month siege, with a huge vaulted ceiling supported by nine columns. Monaco was to remain politically vulnerable for another century and little building work took place from 1581 until 1604, during the reigns of Prince Charles II and Prince Hercule.

Honoré II (1597–1662)

Monaco's vulnerability was further brought home in 1605 when the Spanish installed a garrison there. In 1633 Honoré II (Illustration 8), was officially addressed as "Serene Prince" by the Spanish king, thus recognizing Monaco as a principality for the first time. However, as Spanish troops were currently in occupation, this recognition was seen as little more than a gesture to keep Honoré happy.[10]

Honoré II was a francophile. Following his education in Milan, he had been cultivated by the intellectual salons of Paris.[2] Thus, having close affinities with France both culturally and politically, he rebelled against the Spanish presence in Monaco. While he realised that Monaco needed the protection of another power, France was Honoré II's favoured choice. In 1641, heavily supported by the French, he attacked the Spanish garrison and expelled the Spanish, declaring "the glorious liberty of Monaco".[4] The liberty mentioned was entirely dependent on France, as Monaco now entered a period as a protectorate of France which would last until 1814.[11] As a result of this action Honoré II is today regarded as the hero of Monaco.[4]

Highly educated and a patron of the arts, Honoré II, secure on his throne, began collecting works by Titian, Dürer, Raphael, Rubens and Michelangelo which formed the basis of the art collection that furnished the palace slowly evolving from the Monaco fortress. Over the following 30-year period he transformed it into a palace suitable for a prince (Illustration 9).

He commissioned the architect Jacques Catone not only to enlarge the palace, but also to soften its grim fortified appearance. The main façade facing the square, the "front" of the palace, was given decorative embellishments. The upper loggias (B) to the right of the entrance were glazed. Inside the palace the State Rooms Wing was restyled and the enfilade of state apartments created. A new chapel adorned by a cupola (built on the site marked D) was dedicated to St John the Baptist. This new work helped conceal the forbidding Serravalle Bastion from the courtyard, to create the lighter atmosphere of a Renaissance palazzo.

Absentee landlords and revolution (1662–1815)

During the late 17th century and early 18th century, while Monaco was officially an independent state, it was in reality a province of France.[7] Its rulers spent much of their time at the French court, in this way resembling the absentee landlords so prevalent at the time amongst the French aristocracy. The lure of Versailles was greater than that of their own country.

Honoré II was succeeded by his grandson, Prince Louis I. The new prince had an urbane personality and spent much time with his wife at the French court, where he enjoyed the unusual distinction of being both a foreign head of state and a peer of France. Impressed by the palaces of the French king, who had employed the architect Jean du Cerceau to carry out alterations to the palace at Fontainebleau, Louis I used Fontainebleau as the inspiration for enhancements to his palace at Monaco. Thus he was responsible for two of the palace's most notable features: the entrance—a huge Baroque arch surmounted by a broken pediment bearing the Grimaldi Arms (Illustration 10)—and more memorable still, a double horseshoe staircase modelled on that at Fontainebleau.[12] The thirty steps which compose the staircase are said to have been sculpted from a single block of Carrara marble.[13] Both the architrave of the new entrance and the horseshoe stairs were designed by Antoine Grigho, an architect from Como.[14]

A prince noted for the permissiveness of his private life, Louis I's prodigality was notorious. While visiting England in 1677 he incurred the ire of King Charles II by showering expensive gifts on Hortense Mancini, the king's mistress.[14] The English and Prince Louis later became political enemies when Louis took part in the Anglo-Dutch Wars against England, leading his own Monaco Cavalry into battles in Flanders and Franche-Comté. These acts earned Louis the gratitude of Louis XIV who made him ambassador to the Holy See, charged with securing the Spanish Succession. However, the cost of upholding his position at the papal court caused him to sell most of his grandfather Honoré II's art collection, denuding the palace he had earlier so spectacularly enhanced.[15] Louis died before securing the Spanish throne for France, an act which would have earned the Grimaldi huge rewards. Instead Europe was immediately plunged into turmoil as the War of the Spanish Succession began.

In 1701, Prince Antoine succeeded Louis I and inherited an almost bankrupt Monaco, though he did further embellish the Royal Room. On its ceiling, Gregorio de Ferrari and Alexandre Haffner depicted a figure of Fame surrounded by lunettes illustrating the four seasons. Antoine's marriage to Marie of Lorraine was unhappy and yielded only two daughters.[7] Monaco's constitution confined the throne to members of the Grimaldi family alone, and Antoine was thus keen for his daughter Princess Louise-Hippolyte (Illustration 11) to wed a Grimaldi cousin. However, the state of the Grimaldi fortunes, and the lack of (the politically necessary) approval from King Louis XIV, dictated otherwise. Louise-Hippolyte was married to Jacques de Goyon Matignon, a wealthy aristocrat from Normandy. Louise-Hippolyte succeeded her father as sovereign of Monaco in 1731 but died just months later. The King of France, confirming Monaco's subservient state to France, ignored the protests of other branches of the Grimaldi family, overthrew the Monégasque constitution, and approved the succession of Jacques de Goyon Matignon as Prince Jacques I.[16]

Jacques I assumed the name and arms of the Grimaldi, but the French aristocracy showed scant respect towards the new prince who had risen from their ranks and chose to spend his time absent from Monaco. He died in 1751 and was succeeded by his and Louise-Hippolyte's son Prince Honoré III.[7]

Honoré III married Catherine Brignole[17] in 1757 and later divorced her. Interestingly, before his marriage Honoré III had been conducting an affair with his future mother-in-law.[18] After her divorce Marie Brignole married Louis Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé, a member of the fallen French royal house, in 1798.

Ironically, the Grimaldi fortunes were restored when descendants of both Hortense Mancini and Louis I married: Louise d'Aumont Mazarin married Honoré III's son and heir, the future Honoré IV. This marriage in 1776 was extremely advantageous to the Grimaldi, as Louise's ancestress Hortense Mancini had been the heiress of Cardinal Mazarin. Thus Monaco's ruling family acquired all the estates bequeathed by Cardinal Mazarin, including the Duchy of Rethel, and the Principality of Château-Porcien.[15]

Honoré III was a soldier who fought at both Fontenoy and Rocourt. He was happy to leave Monaco to be governed by others, most notably a former tutor. It was on one of Honoré III's rare visits to the palace in 1767 that illness forced Edward, Duke of York, to land at Monaco. The sick duke was allocated the state bedchamber where he promptly died. Since that date the room has been known as the York Room.

Despite its lack of continuous occupancy, by the final quarter of the 18th century the palace was once again a "splendid place"[19] (Illustration 12). However revolution was afoot, and in the late 1780s Honoré III had to make concessions to his people who had caught the revolutionary ideas from their French neighbours. This was only the beginning of the Grimaldi's problems. In 1793 the leaders of the French Revolution annexed Monaco. The prince was imprisoned in France and his property and estates, including the palace, were forfeited to France.

The palace was looted by the prince's subjects,[2] and what remained of the furnishings and art collection was auctioned by the French government.[20] Further changes were heaped on both the country and palace. Monaco was renamed Fort d'Hercule and became a canton of France while the palace became a military hospital and poorhouse. In Paris, the prince's daughter-in-law Francoise-Thérèse de Choiseul-Stainville (1766–1794)[21] was executed, one of the last to be guillotined during the Reign of Terror.[22] Honoré III died in 1795 in Paris, where he had spent most of his life, without regaining his throne.

19th century

Regaining the palace

Honoré III was succeeded by his son Honoré IV (1758–1819) whose marriage to Louise d'Aumont Mazarin had done so much to restore the Grimaldi fortunes. Much of this fortune had been depleted by the hardships of the revolution. On 17 June 1814 under the Treaty of Paris, the Principality of Monaco was restored to Honoré IV.

The fabric of the palace had been completely neglected during the years in which the Grimaldi had been exiled from Monaco. Such was the state of disrepair that part of the east wing had to be demolished along with Honoré II's bathing pavilion, which stood on the site occupied today by the Napoleon Museum and the building housing the palace archives.

Restoration

Honoré IV died shortly after his throne was restored to him, and structural restoration of the palace began under Honoré V and was continued after his death in 1841 by his brother Prince Florestan. However, by the time of Florestan's accession, Monaco was once again experiencing political tensions caused by financial problems. These resulted from its position as a protectorate of Sardinia, the country to which it had been ceded by France following the end of the Napoleonic wars. Florestan, an eccentric (he had been a professional actor), left the running of Monaco to his wife, Maria Caroline Gibert de Lametz. Despite her attempts to rule, her husband's people were once again in revolt. In an attempt to ease the volatile situation Florestan ceded power to his son Charles, but this came too late to appease the Monégasques. Menton and Roquebrune broke away from Monaco, leaving the Grimaldi's already small country hugely diminished—little more than Monte Carlo.

Florestan died in 1856 and his son, Charles, who had already been ruling what remained of Monaco, succeeded him as Charles III (Illustration 15). Menton and Roquebrune officially became part of France in 1861, reducing Monaco's size at a stroke by 80%. With time on his hands, Charles III now devoted his time to completing the restoration of his palace begun by his uncle Honoré V. He rebuilt St Mary's Tower (Illustration 14) and completely restored the chapel, adding a new altar, and having its vaulted ceiling painted with frescoes, while outside the façade was painted by Jacob Froëschle and Deschler with murals illustrating various heroic deeds performed by the Grimaldi. The Guard Room, the former great hall of the fortress (now known as the State Hall), was transformed by new Renaissance decorations and the addition of a monumental chimneypiece.

Charles III also made serious attempts to find the various works of art and furniture looted, sold and dispersed during the revolution. Together with new purchases, a fine art collection once again adorned the palace which included not only family portraits such as that of Lucien I by de Predis; Honoré II by Philippe de Champaigne; the head of Antoine I by Hyacinthe Rigaud, and van Loo's portrait of Louise-Hyppolyte (Illustration 11) but also such masterpieces as the The Music Lesson by Titian.

Charles III was also responsible for another palace in Monte Carlo, one which would fund his restorations, and turn around his country's faltering economy. This new palace was Charles Garnier's Second Empire casino, completed in 1878 (Illustration 16). The first Monaco casino had opened the previous decade. Through the casino Monaco became self-supporting.[4]

Decline of Grimaldi power

By the time of Charles III's death in 1889, Monaco and Monte Carlo were synonymous as one and the same place, and had acquired, through gambling, a reputation as a louche and decadent playground of the rich. It attracted everyone from Russian grand dukes and railway magnates, often with their mistresses, to adventurers, causing the small country to be derided by many including Queen Victoria.[24] In fact so decadent was Monaco considered that from 1882, when she first began visiting the French Riviera, Queen Victoria refused to make a courtesy social call at the palace.[25] The contemporary writer Sabine Baring-Gould described the habituées of Monaco as "the moral cesspool of Europe."[23]

The successive rulers of Monaco tended to live elsewhere and visit their palace only occasionally. Charles III was succeeded in 1889 by Albert I. Albert married Lady Mary Victoria Douglas-Hamilton, a daughter of Scotland's 11th duke of Hamilton, and his German wife, a princess of Baden. The couple had one son, Louis, before their marriage was annulled in 1880. Albert was a keen scientist and founded the Oceanographic Institute in 1906; as a pacifist he then founded the International Institute of Peace in Monaco. Albert's second wife, Alice Heine, an American banking heiress who was the widow of a French duke, did much to turn Monte Carlo into a cultural centre, establishing both ballet and the opera in the city. Having brought a large dowry into the family she contemplated turning the casino into a convalescent home for the poor who would benefit from recuperation in warm climes.[26] The couple, however, separated before Alice was able to put her plan into action.

In 1910, the palace was stormed during the Monegasque Revolution. The prince pronounced an end to absolute monarchy by promulgating a constitution with an elected parliament the following year.

Albert was succeeded in 1922 by his son Louis II. Louis II had been brought up by his mother and stepfather, HSH Prince Tasziló Festetics de Tolna, in Germany, and did not know Monaco at all until he was 11. He had a distant relationship with his father and served in the French Army. While posted abroad, he met his mistress Marie Juliette Louvet, by whom he had a daughter, Charlotte Louise Juliette, born in Algeria in 1898. As Prince of Monaco, Louis II spent much time elsewhere, preferring to live on the family estate of Le Marchais close to Paris. In 1911 Prince Louis had a law passed legitimising his daughter so that she could inherit the throne, in order to prevent its passing to a distant German branch of the family. The law was challenged and developed into what became known as Monaco succession crisis. Finally in 1919 the prince formally adopted his illegitimate daughter Charlotte, who became known as Princess Charlotte, Duchess of Valentinois.[27] Louis II's collection of artefacts belonging to Napoleon I form the foundation of the Napoleon Museum at the palace, which is open to the public.

During World War II, Louis attempted to keep Monaco neutral, although his sympathies were with the Vichy French Government.[28] This caused a rift with his grandson Rainier, his daughter's son, and the heir[29] to Louis' throne, who strongly supported the Allies against the Nazis.

Following the liberation of Monaco by the Allied forces, the 75-year-old Prince Louis did little for his principality and it began to fall into severe neglect. By 1946 he was spending most of his time in Paris, and on 27 July of that year, he married for the first time. Absent from Monaco during most of the final years of his reign, he and his wife lived on their estate in France. Prince Louis died in 1949 and was succeeded by his grandson, Prince Rainier III.

Rainier III

Prince Rainier III was responsible for not only turning around the fortune and reputation of Monaco but also for overseeing the restoration of the palace. Upon his accession in 1949 Prince Rainier III immediately began a program of renovation and restoration. Many of the external frescoes on the courtyard were restored, while the southern wing, destroyed following the French revolution, was rebuilt. This is the part of the palace where the ruling family have their private apartments.[13] The wing also houses the Napoleon Museum and the archives.

The frescoes decorating the open arcade known as the Gallery of Hercules were altered by Rainier III, who imported works by Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli depicting mythological and legendary heroes.[13] In addition many of the rooms were refurnished and redecorated.[30] Many of the marble floors have been restored in the staterooms and decorated with intarsia designs which include the double R monogram of Prince Rainier III.[2]

Together with his wife, the late Grace Kelly, Prince Rainier not only restored the palace, but from the 1970s also made it the headquarters of a large and thriving business, which encouraged light industry to Monaco, the aim of which was to lessen Monaco's dependence on the income from gambling.[31] This involved land reclamation, the development of new beaches, and high rise luxury housing. As a result of Monaco's increase in prestige, in 1993 it joined the United Nations, with Rainier's heir Prince Albert as head of the Monaco delegation.[32]

Princess Grace predeceased her husband, dying in 1982 as the result of a car accident. When Rainier III died in 2005 he left both his palace and his country in a stronger and more stable state of repair financially and structurally than they had been for centuries.

The palace in the 21st century

Today the palace is home to Prince Rainier's son and successor, Prince Albert II. The state rooms are open to the public during the summer, and since 1960, the palace's courtyard has been the setting for open-air concerts given by Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra (formerly known as the Orchestra of the National Opera).[13]

However, the palace is far more than a tourist attraction and museum: it remains a fully working palace and headquarters of the Monégasque ruler, a fact emphasised by the sentries on constant guard duty at the entrance (Illustration 17). The sovereign princes, although bound by constitution, are involved with the day-to-day running of Monaco as both a country and a business. Today Monaco covers an area of 197 hectares (487 acres) of which 40 hectares (99 acres) have been reclaimed from the sea since 1980.[33]

For important Monégasque events—such as Grimaldi weddings and births—the palace courtyard is opened and the assembled citizens of Monaco are addressed by the prince from the Gallery of Hercules overlooking the courtyard.[13] The courtyard is also used to host the annual children's Christmas party. Through such events, the palace continues to play a central role in the lives of the prince and his subjects, as it has done for over 700 years.

Notes

- ↑ Glatt p.280

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Prince's Palace of Monaco.

- ↑ Lisimachio p. 207.

- 1 2 3 4 The Grimaldis of Monaco.

- ↑ The probability of this legend, related in The Prince's Palace of Monaco, is disputed by some modern historians.

- 1 2 Lisimachio p. 203.

- 1 2 3 4 The House of Grimaldi.

- ↑ The Grimaldis of Monaco states that Jean II was assassinated by his brother, while Lucien points out in The History of Monaco to 1949 that many historians feel that the death following a quarrel between the brothers was accidental.

- 1 2 3 Lisimachio p. 204.

- ↑ The Grimaldis of Monaco states the title was recognized to keep the prince happy, but erroneously cites the date of Spain recognizing the title as 1612. While Honoré II had in fact referred to himself as a prince in documents dating from 1612 and 1619, Spain did not officially acknowledge the title until 1633 (see Monaco: Early History). The official site The Prince's Palace, Monaco also makes a mistake on this matter, stating "Finally in 1480 Lucien Grimaldi persuaded King Charles of France and the Duke of Savoy to recognize the independence of Monaco". This is clearly wrong as in 1480 not only was Louis XI the King of France but Monaco was ruled by Lamberto Grimaldi.

- ↑ Monaco, 'French Protectorate (1641–93)' and 'Annexation (1793–1814)'.

- ↑ de Chimay p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Principauté de Monaco.

- 1 2 de Chimay p. 210.

- 1 2 Monaco: 1662 to 1815.

- ↑ Archbishop Honoré-François Grimaldi, brother of Prince Louis I, was as a celibate priest not considered as a sovereign. His death in 1748 brought to a close the Monaco branch of the Grimaldi family.

- ↑ Sometimes known as Catherine Brignole

- ↑ Marie Catherine Brignole

- 1 2 Lisimachio p. 210.

- ↑ Lisimachio p. 211

- ↑ The daughter of Jacques Philippe de Choiseul, comte de Stainville, a Marshal of France, and Thomase Therese de Clermont d'Amboise, she had married Joseph Grimaldi 6 April 1782. (ThePeerage.com).

- ↑ She shared the tumbrel with André Chénier. The History of Monaco to 1949.

- 1 2 Baring-Gould, p. 244

- ↑ Edwards, pp. 155–157

- ↑ Edwards, p. 169

- ↑ de Fontenoy, p. 87.

- ↑ Glatt, p.55

- ↑ Taraborrelli, p.202

- ↑ Princess Charlotte ceded her succession rights to her son, Rainier, in 1944.

- ↑ Lisimachio.

- ↑ Times Online

- ↑ Glatt p.247

- ↑ Monte Carlo. Société des Bains de Mer.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Princely Palace of Monaco. |

- Lisimachio, Albert (1969). Great Palaces (The Royal Palace, Monaco. Pages 203–211). London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0-600-01682-X.

- de Chimay, Jacqueline (1969). Great Palaces (Fontainebleau. Pages 67–77). London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0-600-01682-X.

- Edwards, Anne (1992). The Grimaldis of Monaco. New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0-688-08837-8.

- Ulino, Maurizio (2008). L'Età Barocca dei Grimaldi di Monaco nel loro Marchesato di Campagna. Napoli: Giannini editore. ISBN 978-88-7431-413-3.

- de Fontenoy, Marquise (1892). Revelation of High Life Within Royal Palaces. The Private Life of Emperors, Kings, Queens, Princes and Princesses. Written From a Personal Knowledge of Scenes Behind the Thrones. Philadelphia: Hubbard Publishing Co.

- Glatt, John (1998). The ruling house of Monaco: the story of a tragic dynasty. London: Judy Piatkus. ISBN 0-7499-1807-1.

- Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2003). Once Upon a Time. New York: Rose Books, Inc. ISBN 0-446-53164-2.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1905). Book of the Riviera. London: Methuen & Co.

- The Prince's Palace of Monaco published by Palais Princier de Monaco. Retrieved 6 February 2007

- Monte Carlo. Société des Bains de Mer published by Société des Bains de Mer. 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2007

- The House of Grimaldi published by Grimaldi.Org. 1999. Retrieved 7 February 2007

- Monaco: Early History written and published by François Velde. 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2007

- Monaco: 1662 to 1815 retrieved 8 February 2007

- The History of Monaco to 1949 published by GALE FORCE of Monaco. Retrieved 9 February 2007

- Principauté de Monaco published by Ministère d'Etat, Monaco. Retrieved 25 February 2007

- Marie Catherine Brignole published by Worldroots.com. Retrieved 15 February 2007

- Times Online, Obituary of Prince Ranier III published by The Times. Retrieved 27 April 2008

Coordinates: 43°43′53.1″N 07°25′12.99″E / 43.731417°N 7.4202750°E