Principality of Halych

| Principality of Halych Галицьке князівство Галицкоє кънѧжьство | |||||

| Principality of the Kievan Rus' | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Halych | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Succeeded from Peremyshl-Terebovlia Principality | 1124 | |||

| • | United with Volyn Principality | 1199 (1205-1239) | |||

| Political subdivisions | Principalities of Kievan Rus | ||||

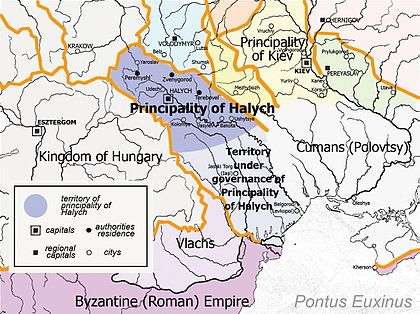

Principality of Halych (Ukrainian: Галицьке князівство, Old East Slavic: Галицкоє кънѧжьство, Romanian: Cnezatul Halici) was a Kievan Rus' principality established by members of the oldest line of Yaroslav the Wise descendants. A characteristic feature of Halych principality was an important role of the nobility and citizens in political life, consideration a will of which was the main condition for the princely rule.[1] Halych as the capital mentioned in around 1124 as a seat of Ivan Vasylkovych the grandson of Rostislav of Tmutarakan. According to Mykhailo Hrushevsky the realm of Halych was passed to Rostyslav upon the death of his father Vladimir Yaroslavich, but he was banished out of it later by his uncle to Tmutarakan.[2] The realm was then passed to Yaropolk Izyaslavich who was a son of the ruling Grand Prince of Kiev Izyaslav I of Kiev.

Prehistory

First Slavic tribes living in Galicia were Croats and Dulebs. There are some claims of temporarily belonging of this territory to the Great Moravian state and later probably Duchy of Bohemia. In year 907 Galician Croats and Dulebs were involved in military campaign against Constantinople led by Rus` Prince Oleg of Novgorod.[3][4] This is the first significant evidence of political affiliation of native tribes of Galicia. According to Nestor the Chronicler some strongholds in West Part of Galicia were conquered by Vladimir the Great in 981, and in 983 Vladimir carried out military campaign against the Croats.[5] Around that time the city of Volodymyr was established in honor of him which became the main center of political power in the region. In the 11th century western border citys including Peremyshl, were twice annexed by the Kingdom of Poland (1018–1031, and 1069–1080). In the meantime, Yaroslav the Wise established a "solid foot" in the region founding the city of Jarosław.

As part of the Kievan Rus' the area was later organized as South part of Volodymyr Principality, where around 1085 with the help of the Grand Prince of Kiev Vsevolod I of Kiev the three Rostystlavych Brothers - sons of Rostislav Vladimirovich (of Tmutarakan) settled. Their lands were organized into three smaller principalities of Peremyshl, Zvenyhorod and Terebovlia. In 1097 the Terebovlia Principality was secured after Vasylko Rostyslavych by the Council of Liubech after several years of a civil war. In 1124 the Halych Principality as minor principality was given to Ihor Vasylkovich by his father Vasylko, the Prince of Terebovlia out of the Terebovlia Principality.

Unification

Rostislavich Brothers managed not only politically separate from Volodymyr, but also to defend themselves from external enemies. In 1099, in the battle on Rozhne field halycians defeated army of the Grand Prince Sviatopolk II of Kiev and later that year army of Hungarian king Coloman near Peremyshl.[6]

This two significant victories brought nearly one hundred years of relative peaceful development of Halycian principality.[7] Four sons of Rostystlavych Brothers divided the area into four parts with centers in Peremyshl (Rostislav), Zvenyhorod (Volodymyrko), Halych and Terebovlia (Ivan and Yuriy). After the death of three of them Volodimyrko took Peremyshl and Halych and Zvenyhorod gave to Ivan - son of his older brother Rostyslav. In 1141 Volodymyrko moved his residence from Peremyshl to more geographically advantageous Halych giving birth to a united Halycian Principality. In 1145 citizens of Halych, taking advantage of the absence of Volodymyrko, called to reign Ivan of Zvenyhorod. After the defeat of Ivan under the walls of Halych, also Zvenygorod principality was incorporated into the Halycian.

Era of Yaroslav Osmomysl

Volodymyrko pursued a policy of balancing between neighbors managed to strengthen the power of the principality, attach some cities belonging to the Kiev Grand Prince and forced to keep them despite the conflict with both two powerful rulers Iziaslav II of Kiev and king Géza II of Hungary.[8]

In 1152, after the death of Volodymyrko, Halycian throne was succeeded by his only son Yaroslav Osmomysl. Yaroslav begins his reign with the Battle on the river Siret in 1153 with Grand Prince Iziaslav, which resulted a heavy losses for the Halycians but retreat of Izyaslav, who died shortly thereafter. Thus the danger from the east had passed and Jaroslav via diplomacy reached peace with his other neighbors - Hungary and Poland. Subsequently, thanks to negotiations Jaroslav neutralized his only rival - the eldest descendant of Rostislavich Brothers Ivan, former Prince of Zvenyhorod.

These diplomatic successes have enabled Yaroslav to focus on internal development of Principality: construction of new buildings in capital and other cities, enrichment of monasteries, as well as strengthening his power over the territory in lower courses of Dniester, Prut and Danube rivers. Within this time (around 1157) in Halych were completed a construction of Assumption Cathedral - second largest temple of Ancient Rus after St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev,[9] the city itself grew into a big agglomeration [10] with approximate dimensions of 11 x 8.5 kilometers.[11] Despite strong position in the international arena Yaroslav was under control of Halych citizens will of which he had to consider even sometimes in matters of personal family life.

”Freedom in princes”

Significant feature in political life of Halycian principality was decisive role of nobles and citizens. Halicyans used the principle of ″freedom in princes″ and themselves invited and expelled princes also correcting their activities. Despite the will of Yaroslav Osmomysl who left the throne to his younger son Oleg, Halycians invited his brother Vladimir II Yaroslavich, and later after conflict with him Roman the Great prince of Volodymyr. But almost immediately Roman was replaced by Andrew - the son of Hungarian King Bela III. The reason for this choice was a complete freedom of government that was guaranteed by Bella and Andrew to Halycians.[12] This period can be considered as the first experience of self-rule government by noblemen and citizens. However, vulgar behavior of the Hungarian garrison and their attempts to install Roman Catholic rites[13] led to another change in mood and to the throne againe was returned Vladimir II, who ruled in Halych next decade up to year 1199.

Autocracy of Roman the Great and unification with Volhynia

After the death of last descendant of Principality`s founders Rostislavich Brothers - Vladimir II in 1199, Halycians started negotiations with the sons of his sister (daughter of Yaroslav Osmomysl) and the legendary Prince Igor (the main hero of the poem The Tale of Igor's Campaign) about succession to the Galician throne. But Prince of Volodymir Roman with the help of Prince Leszek the White managed to capture Halych despite a strong resistance of residents.[14] Following next six years lasted a period of continued repression against the nobility and active citizens as well as a significant territorial and political expansion that transformed Halych in the main center of all Rus`. Volhynian principality was united with Halycian but this time the new Centre of Galicia-Volhynia principality became Halych. Further successful war with Igorevich Brothers contenders for the Galician throne enabled Roman the Great to establish his control over Kiev and place there his henchmens, one of them with the consent of Vsevolod the Big Nest. After victorious campaigns against the Cumans, and probably Lithuanians, Roman the Great reached the height of its power and was called in the annals as "The Tzar and Autocrator of all Rus`".[15][16][17] After the death of Roman in 1205, his widow to keep power in Halycia called for help Hungarian King Andrew, which sent her the military garrison. However, in next 1206 year Halycians again invited Vladimir III Igorevich - son of Yaroslav Osmomysl`s daughter, and Roman widow, along with the sons had to flee the city.

Climax of citizens-nobles rule

Vladimir III reigned in Galicia only two years. As a result of feuds with his brother Roman II, he was expelled and the latter took the Galician throne. But very soon Roman was replaced by Rostislav II of Kiev. When Roman II managed to overthrow Rostislav Halycians called for help Hungarian king who sent to Halych palatine Benedict.[18] While Benedict remained in Halych citizens called to the throne Prince Mstislav the Dumb from Peresopnytsya, who also with ridicules sent home. In an effort to get rid of Benedict citizens again invited Ihrevychiv Brothers - Vladimir III and Roman II who expelled Benedict and regained their rule in the Principality. Vladimir III settled in Halych, Roman II in Zvenigorod and their brother Svyatoslav in Peremyshl. Attempts of Igorevich Brothers to rule themselves led to conflict with the Halycians during which many of them was killed,[19] and later Igorevich Brothers was executed. On the throne was planted a young son of Roman the Great Daniel of Galicia. After his mother made an attempt to concentrate power in his hands as regent, she was banished from the city, and to reign was again invited Mstislav the Dumb who fled fearing Hungarian troops have been called by of Daniel`s mother. After the failure of Hungarian King`s campaign, the local community has made a unique step in the history of Rus`, enthroned in 1211 or 1213[20] one of the Halycian noble[21][22] Volodyslav Kormylchych. This episode can be considered as a peak of citizens-nobles democracy in Halych.

Rule of Volodyslav caused aggression of neighboring states and in spite of the halycian`s resistance they managed to overwhelm Volodyslav`s army. In 1214 Hungarian King Andrew and Polish Prince Leszek signed an agreement about partition of Halycian principality. The western edge passed to Poland and the rest to Hungary. Palatine Benedict returned to Halych and the son of Hungarian king Andrew Koloman, received the crown from the Pope with the title of "King of Galicia." However, religious conflict with the local population[23] and capture by Hungarians territory that was transferred to Poland, led to the expulsion in 1215 of all foreign forces and the enthronement of Prince Mstislav the Bold from Novgorod under whose reign all power was concentrated in the hands of the nobility[24][25][26] and Prince not disposed even Halycian army. Despite this Mstislav also was not popular among the Halycians, who gradually began to favor Prince Andrew.[27][28] In 1227 Mstislav allowed his daughter to marry him and gave them government in Galicia. Andrew has been a long time favorite of Galicia due to its careful approach to the rights of the nobility. However, in 1233 part of Halycians invited Daniel. As a result of the siege and the death of Andrew Daniel briefly seized the capital, but was forced to leave it not finding support of citizens majority. In 1235, at the invitation of Halycians to the city came Chernigov Prince Michael of Chernigov and his son Rostislav (his mother was the daughter of Roman the Great, the sister of Daniel).[29] During the Mongol invasion, Halych turns in the hands of Daniel, but his power was not certain, because at this time chronicle mentions an ascension to the throne a loсal nobleman Dobroslav Suddych.[30]

Daniel of Galicia and Mongol invasion

In the 40-th years of the XIII century in Halycian Principality`s history occurred an important changes. In 1241 Наlych was captured by the Mongol army.[31] In 1245 Daniel wins a decisive victory over the Hungarian-Polish army of his opponent Rostislav and again unites Halycia with Volhynia. After the victory he makes a series of repressions of Halycian nobles and build his residence in Holm in the western part of Volhynia. After Daniel`s visit to Batu Khan, started payments of tribute to Golden Horde. All these factors led to the beginning of cultural, economic and political decline of Halych.

Last rise and decline

Already in time of Daniel`s rule Halycia turned to the hands of his elder son Leo I of Galicia, who after his father's death gradually takes power in all areas of Volhyn. In the second half of the thirteenth century, raised the importance of Lviv - a new political-administrative center, founded near Zvenigorod on the border with Volhyn. Near 1300 Leo in a short time can achieve power over Kiev, remaining however dependent on the Golden Horde. After the death of Leo, the center of Uniated Galician-Volynian state returns to the city of Volodymyr. In the times of following princes, nobles gradually concentrated power again, and from 1341 to 1349 it actually remain in the hands of a nobleman Dmytro Dedko at nominal reign of prince Liubart.[32] In 1349, after the death of Dmytro, Polish King Casimir III the Great provides military march on Lviv which was coordinated with the Golden Horde[33] and the Hungarian kingdom.[34] The result was the end of political independence of Halycian principality and its incorporation to the possessions of Polish king. At the same time a Black Death eroded human and economic potential of the region, which has turned into an object of rivalry between Hungary, Poland and Lithuania.

Post-history

In 1387 all lands of the Halycian principality were included in to the possessions of Polish Queen Jadwiga, and later in 1434 transformed into Ruthenian Voivodeship. Some indigenous population were driven from their land and moved in Tatar`s possessions.[35][36] In 1772, Halycia was attached to the Austrian Empire within which it existed as an administrative unit called "Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria" with the center in Lviv .

Relations with Byzantine Empire

Halycian Principality had a close ties with Byzantine Empire, closest than any other principality of Kievan Rus. According to some records, Volodar of Peremyshl`s daughter Irina was married in 1104 to Isaac - third son of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos.[37] Her son, future Emperor Andronicus I Comnenus some time lived in Halych and ruled by several cities of principality in years 1164-65.[38][39] According to reports of Bartholomew of Lucca Byzantine Emperor Alexius III fled to Halych after the capture of Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204.[40][41] Halycian principality and Byzantine Empire were frequent allies in the fight against Cumans.

Princes of Halych

| Princes of Halych (according to М. Hrushevsky) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prince | Years | Remarks |

| Ivan Vasylkovych | 1124–1141 | son of Vasylko Rostyslavych of Terebovel` (not mentioned in Hrushevsky list) |

| Volodymyrko Volodarovych | 1141–1144 | son of Prince of Przemysl Volodar Rostyslavych |

| Ivan Rostyslavych Berladnyk | 1144 | son of Prince of Peremyshl` Rostyslav Volodarovych (not mentioned in Hrushevsky list) |

| Volodymyrko Volodarovych | 1144–1153 | second time |

| Yaroslav Osmomysl | 1153–1187 | son of Volodymyrko Volodarovych |

| Oleg Yaroslavich | 1187 | son of Yaroslav Osmomysl |

| Volodymyr Yaroslavych | 1187–1188 | son of Yaroslav Osmomysl |

| Roman Mstyslavych | 1188–1189 | Prince of Volhynia |

| Volodymyr Yaroslavych | 1189–1199 | son of Yaroslav Osmomysl, second time |

| Roman Mstyslavych | 1199–1205 | second time |

| Daniel Romanovych | 1205–1206 | son of Roman Mstyslavych |

| Volodimir III Igorevich | 1206–1208 | from Chernihov line of Rurik dynasty |

| Roman II Igorevich | 1208–1209 | brother of Volodymyr Igorevych |

| Rostislav II of Kiev | 1210 | son of Rurik Rostislavich of Kiev |

| Roman II Igorevich | 1210 | second time |

| Volodimir III Igorevich | 1210–1211 | second time |

| Daniel Romanovych | 1211–1212 | second time |

| Mstyslav of Peresopnytsia | 1212–1213 | from Volhynian line of Rurik dynasty |

| Volodyslav Kormyl`chych | 1213–1214 | boyar from Halych |

| Coloman II | 1214–1219 | son of Andrew II of Hungary |

| Mstyslav the Bold | 1219 | from Kievan line of Rurik dynasty, grandson of Yaroslav Osmomysl (by female line) |

| Coloman II | 1219–1221? | second time |

| Mstyslav the Bold | 1221?-1228 | second time |

| Аndiy Andrievych | 1228–1230 | son of Andrew II of Hungary |

| Daniel Romanovych | 1230–1232 | third time |

| Аndiy Andrievych | 1232–1233 | second time |

| Daniel Romanovych | 1233–1235 | fourth time |

| Michael Vsevolodovich | 1235–1236 | from Chernihov line of Rurik dynasty |

| Rostislav Mikhailovich | 1236–1238 | son of Michael Vsevolodovich, from Chernihov line of Rurik dynasty |

| Daniel Romanovych | 1238–1264 | fifth time |

| Shvarn Danilovych | 1264–1269 | son of Daniel, co-ruler of Leo I of Galicia |

| Lev I Danilovich | 1264–1301? | son of Daniel |

| Yuri I L`vovych | 1301?-1308? | son of Lev I |

| Lev II Yurievych | 1308–1323 | son of Yuri I |

| Volodymyr Lvovych | 1323–1325 | son of Lev II |

| Yuri II Boleslav | 1325–1340 | from Mazovian princes, grandson of Yuri I |

| Dmitriy Liubart | 1340–1349 | from Lithuanian princes |

References

- ↑ Майоров А. В.. Галицко-Волынская Русь. Очерки социально-политических отношений в домонгольский период. Князь, бояре и городская община. СПб., Университетская книга. 640 с., 2001

- ↑ Грушевський. Історія України-Руси. Том II. Розділ VII. Стор. 1.

- ↑ "Oleg of Novgorod | History of Russia". historyofrussia.org. Retrieved 2016-02-14.

- ↑ Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 21

- ↑ ЛІТОПИС РУСЬКИЙ. Роки 988 — 1015.

- ↑ Font, Márta (2001). Koloman the Learned, King of Hungary (Supervised by Gyula Kristó, Translated by Monika Miklán). Márta Font (supported by the Publication Commission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Pécs). p. 73.ISBN 963-482-521-4.

- ↑ М. Грушевський. Історія України-Руси. Том II. Розділ VII. Стор. 1.

- ↑ Makk, Ferenc (1989). The Árpáds and the Comneni: Political Relations between Hungary and Byzantium in the 12th century (Translated by György Novák). Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 47. ISBN 963-05-5268-X

- ↑ Пастернак Я. Старий Галич: Археологічно-історичні досліди в 1850 - 1943 рр. - Краків, Львів, -1944р., - С. 66, 71-72,

- ↑ Петрушевичъ А. 1882–1888 Критико-исторические рассуждения о надднестрянскомъ городе Галичъ и его достопамятностях // Льтопись Народного Дома. – Львов. – С. 7–602.

- ↑ Могитич Р. Містобудівельний феномен давнього Галича // Галицька брама. – Львів. 1998 – № 9. – С. 13–16

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 661

- ↑ Dimnik, Martin (2003). The Dynasty of Chernigov, 1146–1246. Cambridge University Press. p.193 ISBN 978-0-521-03981-9.

- ↑ W.Kadłubek Monum. Pol. hist. II 544-7

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 715

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 808

- ↑ Майоров А.В. Царский титул галицко-волынского князя Романа Мстиславича и его потомков//Петербургские славянские и балканские исследования 2009 # 1/2 (5/6)

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб.722

- ↑ M. Hrushevsky History of Ukraine-Rus Volume III Knyho-Spilka, New-York 1954 -P.26

- ↑ Грушевський М.С. Хронольогія подій Галицько-Волинської літописи // ЗНТШ. Львів, 1901. Т. XLI C.12

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 729

- ↑ Фроянов И.Я., Дворниченко А.Ю. Города-осударства Юго-Западной Руси. Л., 1988. С.150

- ↑ Huillard-Breholles Examen de chartes de l'Eglise Romaine contenues dans les rouleaux de Cluny, Paris, 1865, 84

- ↑ Крип’якевич І.П. Галицько-Волинське князівство. Київ, 1984. С.90

- ↑ Софроненко К.А. Общественно-политический строй Галицко-Волінской Руси ХІ - ХІІІ вв. М.1955.С.98

- ↑ Софроненко К.А. Общественно-политический строй Галицко-Волынской Руси ХІ - ХІІІ вв. М.1955.С.98

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 787

- ↑ Шараневич И.И. История Галицко-Володимирской Руси от найдавнейших времен до року 1453. Львов, 1863. С.79

- ↑ M. Hrushevsky History of Ukraine-Rus Volume III Knyho-Spilka, New-York 1954 -P.54

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 789

- ↑ ПСРЛ. — Т. 2. Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 786

- ↑ M.Hrushevsky History of Ukraine-Rus`- Volume IV Knyho-Spilka, New York 1954 -P.20

- ↑ ``nuncii Tartarorum venerunt ad Regem Poloniae. Et in fine eiusdem anni Rex Kazimirus terram Russiae obtinuit`` Monum. Poloniae hist. II c. 885

- ↑ M.Hrushevsky History of Ukraine-Rus`- Volume IV Knyho-Spilka, New York 1954 -P.35

- ↑ Греков Б.Д. 1946. Крестьяне на Руси. М.-Л. -С.257

- ↑ Полевой Л.Л. 1979. Очерки исторической географии Молдавии XIII-XV вв. Кишинев -С.38

- ↑ Hypatian Codex Ипатьевская летопись. — СПб., 1908. — Стлб. 256

- ↑ Nicetae Choniatae histoia. Rec. I. Bekker. Bonnae 1835, p. 168–171, 172–173(lib. IV, cap. 2; lib. V, cap. 3)

- ↑ Tiuliumeanu M. Andronic I Comnenul. Iasi 2000.

- ↑ Girgensonn J. Kritische Untersuchung über das VII. Buch der Historia Polonica des Dlugosch. Göttingen 1872, s. 65.

- ↑ Semkowicz A. Krytyczny rozbiór Dziejów Polskich Jana Dlugosza (do roku 1384). Kraków 1887, s. 203.

Bibliography

- Hrushevsky, M. History of Ukraine-Rus. Saint Petersburg, 1913.

- History of Ukraine-Rus. Vienna, 1921.

- Illustrated history of Ukraine. "BAO". Donetsk, 2003. ISBN 966-548-571-7 (Chief Editor - Iosif Broyak)