Public aquarium

A public aquarium (plural: public aquaria or public aquariums) is the aquatic counterpart of a zoo, which houses living aquatic animal and plant specimens for public viewing. Most public aquariums feature tanks larger than those kept by home aquarists, as well as smaller tanks. Since the first public aquariums were built in the mid-19th century, they have become popular and their numbers have increased. Most modern accredited aquariums stress conservation issues and educating the public.[1]

History

The first public aquarium was opened in London Zoo in May 1853; the Fish House, as it came to be known, was constructed much like a greenhouse.[2] P.T. Barnum quickly followed in 1856 with the first American aquarium as part of his established Barnum's American Museum, which was located on Broadway in New York City before it burned down.[2] In 1859, the Aquarial Gardens were founded in Boston.[2] A number of aquariums then opened in Europe, such as the Jardin d'Acclimatation in Paris and the Viennese Aquarium Salon (both founded 1860), the Marine Aquarium Temple as part of the Zoological Garden in Hamburg (1864), as well as aquariums in Berlin (1869) and Brighton (1872).[2]

The old Berlin Aquarium opened in 1869. The building site was to be Unter den Linden (along a major avenue), in the centre of town, not at the Berlin Zoo. The aquarium's first director, Alfred Brehm, former director of the Hamburg Zoo from 1863 to 1866, served until 1874.[3] With its emphasis on education, the public aquarium was designed like a grotto, part of it made of natural rock. The Geologische Grotte depicted "the strata of the earth's crust". The grotto also featured birds and pools for seals. The Aquarium Unter den Linden was a three-story building. Machinery and water tanks were on the ground floor, aquarium basins for the fish on the first floor. Because of Brehm's special interest in birds, a huge aviary, with cages for mammals placed around it, was located on the second floor. The facility closed in 1910.[4]

The Artis aquarium at Amsterdam Zoo was constructed inside a Victorian building in 1882, and was renovated in 1997. At the end of the 19th century the Artis aquarium was considered state-of-the-art, as it was again at the end of the 20th century.[5]

Prior to its closing on September 30, 2013, the oldest American aquarium was the National Aquarium in Washington, D.C., founded in 1873.[6] This was followed by the opening of other public aquariums: San Francisco (Woodward's Garden, 1873–1890), Woods Hole (Science Aquarium, 1885), New York (Battery Park, 1896–1941), La Jolla (Scripps, 1903), Honolulu (Waikiki Aquarium 1904–present), Detroit (Belle Isle Aquarium, 1904–2005, 2012–Present), Philadelphia (Fairmount Water Works, 1911–1962), San Francisco (Steinhart Aquarium, 1923), Chicago (Shedd Aquarium, 1929). For many years, the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago was the largest aquarium in the United States, until the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta opened. Entertainment and aquatic circus exhibits were combined as themes in Philadelphia's Aquarama Aquarium Theater of the Sea (1962–1969) and Camden's re-invented Adventure Aquarium 2005, formerly the New Jersey State Aquarium (1992).

The first Japanese public aquarium, a small freshwater aquarium, was opened at the Ueno Zoo in 1882.[7]

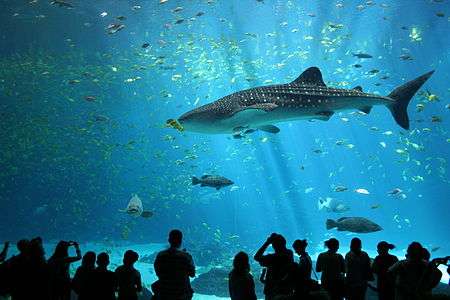

In 2005, the Georgia Aquarium, with more than 8 million U.S. gallons (6.7 million imp gal; 30 million L) of marine and fresh water, and more than 100,000 animals of 500 different species opened in Atlanta, Georgia. The aquarium's notable specimens include whale sharks and beluga whales.

Public aquariums today

Modern aquarium tanks can hold millions of litres of water and can house large species, including dolphins, sharks or beluga whales. This is accomplished through thick, clear acrylic glass windows. Aquatic and semiaquatic mammals, including otters,[8] and seals[9] are often cared for at aquariums. Some establishments, such as the Oregon Coast Aquarium or the Monterey Bay Aquarium, have aquatic aviaries.[10][11] Modern aquariums also include land animals and plants that spend time in or near the water.[12]

For marketing purposes, many aquariums promote special exhibits, in addition to their permanent collections. Some have aquatic versions of a petting zoo. The Monterey Bay Aquarium has a shallow tank filled with common types of rays[13] which visitors are encouraged to touch. The South Carolina Aquarium lets visitors feed the rays in their Saltmarsh Aviary exhibit.[14]

Logistics

Most public aquariums are located close to the ocean, for a steady supply of natural seawater. An inland pioneer was Chicago's Shedd Aquarium[15] that received seawater shipped by rail in special tank cars. The early (1911) Philadelphia Aquarium, built in the city's disused water works, had to switch to treated city water when the nearby river became too contaminated.[16] Similarly, the recently opened Georgia Aquarium filled its tanks with fresh water from the city water system and salinated its salt water exhibits using the same commercial salt and mineral additives available to home aquarists. The South Carolina Aquarium pulls the salt water for their exhibits right out of the Charleston harbor.

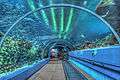

In January 1985, Kelly Tarlton began construction of the first aquarium to include a large transparent acrylic tunnel, Kelly Tarlton's Underwater World in Auckland, New Zealand. Construction took 10 months and cost NZ$3 million. The 110-metre (360 ft) tunnel was built from one-tonne (2,200-lb) slabs of German sheet plastic that were shaped locally in an oven. A moving walkway now transports visitors through, and groups of school children occasionally hold sleepovers there beneath the swimming sharks and rays.[17]

Activities

Public aquariums are often affiliated with oceanographic research institutions or conduct their own research programs, and sometimes specialize in species and ecosystems that can be found in local waters. For example, the Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, BC is a major center for marine research, conservation, and marine animal rehabilitation, particularly for the rich ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest.[18] The Vancouver Aquarium was the first aquarium to capture and display an orca whale, Moby Doll, for three months in 1964; as well as belugas, narwhals[19] and dolphins. The Monterey Bay Aquarium was the first public aquarium to display a great white shark. Beginning in September 2004, the Outer Bay exhibit (now the Open Sea galleries) was the home to the first in a series of great white sharks. The shark was at the aquarium for 198 days (the previous record was 16 days). The shark was released on March 31, 2005. The Adventure Aquarium in New Jersey has hippos. The Aquarium du Quebec houses polar bears.

A great white shark in temporary captivity at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

A great white shark in temporary captivity at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Baltimore Aquarium

Baltimore Aquarium Aquarium in shopping mall

Aquarium in shopping mall Churaumi Aquarium

Churaumi Aquarium al Mahara restaurant

al Mahara restaurant Dubai Aquarium

Dubai Aquarium exhibit tunnel at Georgia Aquarium

exhibit tunnel at Georgia Aquarium

See also

References

- ↑ Visitor Impact, AZA official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Brunner, Bernd (2003). The Ocean at Home. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 99. ISBN 1-56898-502-9.

- ↑ Strehlow, Harro, "Zoos and Aquariums of Berlin" in New World, New Animals: From Menagerie to Zoological Park in the Nineteenth Century, Hoage, Robert J. and Deiss, William A. (ed.), Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1996, p.69. ISBN 0-8018-5110-6

- ↑ Strehlow, Harro, "Zoos and Aquariums of Berlin" in New World, New Animals: From Menagerie to Zoological Park in the Nineteenth Century, Hoage, Robert J. and Deiss, William A. (ed.), Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1996, p.70. ISBN 0-8018-5110-6

- ↑ Van Bruggen, A.C., "Notes on the Buildings of Amsterdam Zoo", International Zoo News Vol.49/6 (No.319), September 2002.

- ↑ David Lin, former Director of Operations, National Aquarium, Washington, DC

- ↑ Kawata, Ken, "Zoological Gardens of Japan", in Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Collections to Zoological Gardens, Kisling, Vernon N. (ed.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2001, p.298. ISBN 0-8493-2100-X

- ↑ Sea Otters, Oregon Coast Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Seals, Oregon Coast Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Birds, Oregon Coast Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Sandy Shores, Monterey Bay Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Taylor, Leighton R., Aquariums: Windows to Nature, Prentice Hall General Reference, New York, 1993. ISBN 0-671-85019-9

- ↑ Sharks and Rays, Monterey Bay Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ "Saltmarsh Aviary". scaquarium.org. South Carolina Aquarium. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Shedd History, Shedd Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ , Philadelphia Inquirer article, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Kelly Tarlton's Antarctic Encounter and Underwater World, Auckland

- ↑ Research, Vancouver Aquarium's official website, accessed February 3rd, 2007.

- ↑ Narwhal (Monodon monoceros)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aquariology. |

- Norfolk, Howard. My Visit to the Freshwater Public Aquarium in Havana, Cuba, Aquarticles.com, January 2004, retrieved on: June 22, 2007

- Case Studies in Aquarium History

- Sao Paulo's Aquarium (Aquário de São Paulo) - Brazil

- Public aquariums in the United States

- A map of public aquaria around the world