Rape of Belgium

The Rape of Belgium is the historical term used to refer to the German treatment of civilians during the invasion and subsequent occupation of Belgium during World War I. The term initially had a propaganda use but recent historiography confirms its reality.[1] One modern author uses it more narrowly to describe a series of German war crimes in the opening months of the War (August–September 1914).[2]

The neutrality of Belgium had been guaranteed by the Treaty of London (1839), which had been signed by Prussia. However, the German Schlieffen Plan required that German armed forces violate Belgium’s neutrality in order to outflank the French Army, concentrated in eastern France. The German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg dismissed the treaty of 1839 as a "scrap of paper".[3] Throughout the beginning of the war the German army engaged in numerous atrocities against the civilian population of Belgium, and destruction of civilian property; 6,000 Belgians were directly killed, 17,700 died during expulsion, deportation, in prison or sentenced to death by court.[4] 25,000 homes and other buildings in 837 communities destroyed in 1914 alone, one and a half million Belgians (20% of the entire population) fled from the invading German army.[5]:13

War crimes

.jpg)

In some places, particularly Liège, Andenne and Leuven, but firstly Dinant, there is evidence that the violence against civilians was premeditated.[5]:573–4 However, in Dinant, the German army believed the inhabitants were as dangerous as the French soldiers themselves.[6][7] German troops, afraid of Belgian guerrilla fighters, or francs-tireurs, burned homes and executed civilians throughout eastern and central Belgium, including Aarschot (156 dead), Andenne (211 dead), Seilles, Tamines (383 dead), and Dinant (674 dead).[8] The victims included women and children.[9]

On August 25, 1914, the German army ravaged the city of Leuven, deliberately burning the university's library of 300,000 medieval books and manuscripts with gasoline, killing 248 residents,[10] and expelling the entire population of 10,000. However, contrary to what many believe and write, it was not the books of the Old University of Leuven which disappeared in smoke; indeed, in 1797, the manuscripts and most valuable works of this university were transported[11] to the National Library in Paris and much of the old library was transferred to the Central School of Brussels, the official and legal successor of the Old University of Leuven. The library of the Central School of Brussels had about 80,000 volumes, which then came to enrich the library of Brussels, and then the future Royal Library of Belgium where they are still. Civilian homes were set on fire and citizens often shot where they stood.[12] Over 2000 buildings were destroyed and large quantities of strategic materials, foodstuffs, and modern industrial equipment were looted and transferred to Germany in 1914 alone. These actions brought worldwide condemnation.[13] (There were also several friendly fire incidents between groups of German soldiers during the confusion.[7]) Overall, the Germans were responsible for the killing of 23,700 Belgian civilians, (6,000 Belgians directly killed, 17,700 died during expulsion, deportation, in prison or sentenced to death by court) and caused further nonfatalities of 10,400 permanent and 22,700 temporary invalids, with 18,296 children becoming war orphans. Military losses were 26,338 killed, died from injuries or accidents, 14,029 died from disease, or went missing.[4]

In the Province of Brabant, nuns were ordered by Germans to strip naked under the pretext that they were spies or men in disguise. Nevertheless, there's no evidence that nuns were violated. In and around Aarschot, between August 19 and the recapture of the town by September 9, women were repeatedly victimised. Rape was nearly as ubiquitous as murder, arson and looting, if never as visible.[5]:164–165

Wartime propaganda

Agreeing with the analysis of historian Susan Kingsley Kent, historian Nicoletta Gullace writes that "the invasion of Belgium, with its very real suffering, was nevertheless represented in a highly stylized way that dwelt on perverse sexual acts, lurid mutilations, and graphic accounts of child abuse of often dubious veracity."[14]:19 In Britain, many patriotic publicists propagated these stories on their own. For example, popular writer William Le Queux described the German army as "one vast gang of Jack-the-Rippers", and described in graphic detail events such as a governess hanged naked and mutilated, the bayoneting of a small baby, or the "screams of dying women", raped and "horribly mutilated" by German soldiers, accusing them of cutting off the hands, feet, or breasts of their victims.[14]:18–19

Gullace argues that "British propagandists were eager to move as quickly as possible from an explanation of the war that focused on the murder of an Austrian archduke and his wife by Serbian nationalists to the morally unambiguous question of the invasion of neutral Belgium". In support of her thesis, she quotes from two letters of Lord Bryce. In the first letter Bryce writes "There must be something fatally wrong with our so-called civilization for this Ser[b]ian cause so frightful a calamity has descended on all Europe". In a subsequent letter Bryce writes "The one thing we have to comfort us in this war is that we are all absolutely convinced of the justice of the cause, and of our duty, once Belgium had been invaded, to take up the sword".[14]:20

Although the infamous German phrase "scrap of paper" (referring to the 1839 Treaty of London) galvanized a large segment of British intellectuals in support of the war,[14]:21–22 in more proletarian circles this imagery had less impact. For example, Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald upon hearing about it, declared that "Never did we arm our people and ask them to give up their lives for a less good cause than this". British army recruiters reported problems in explaining the origins of the war in legalistic terms.[14]:23

As the German advance in Belgium progressed, British newspapers started to publish stories on German atrocities. The British press, "quality" and tabloid alike, showed less interest in the "endless inventory of stolen property and requisitioned goods" that constituted the bulk of the official Belgian Reports. Instead, accounts of rape and bizarre mutilations flooded the British press. The intellectual discourse on the "scrap of paper" was then mixed with the more graphic imagery depicting Belgium as a brutalized woman, exemplified by the cartoons of Louis Raemaekers,[14]:24 whose works were widely syndicated in the US.[15]

Part of the press, such as the editor of The Times and Edward Tyas Cook, expressed concerns that haphazard stories, a few of which were proven as outright fabrications, would weaken the powerful imagery, and asked for a more structured approach. The German and American press questioned the veracity of many stories, and the fact that the British Press Bureau did not censor the stories put the British government in a delicate position. The Bryce Committee was eventually appointed in December 1914 to investigate.[14]:26–28 Bryce was considered highly suitable to lead the effort because of his prewar pro-German attitudes and his good reputation in the United States, where he had served as Britain's ambassador, as well as his legal expertise.[14]:30

The commission's investigative efforts were, however, limited to previously recorded testimonies. Gullace argues that "the commission was in essence called upon to conduct a mock inquiry that would substitute the good name of Lord Bryce for the thousands of missing names of the anonymous victims whose stories appeared in the pages of the report". The commission published its report in May 1915. Charles Masterman, the director of the British War Propaganda Bureau, wrote to Bryce: "Your report has swept America. As you probably know even the most skeptical declare themselves converted, just because it is signed by you!"[14]:30 Translated in ten languages by June, the report was the basis for much subsequent wartime propaganda and was used as a sourcebook for many other publications, ensuring that the atrocities became a leitmotif of the war's propaganda up to the final "Hang the Kaiser" campaign.[14]:31–23

For example, in 1917 Arnold J. Toynbee published The German Terror in Belgium, which emphasized the most graphic accounts of "authentic" German sexual depravity, such as: "In the market-place of Gembloux a Belgian despatch-rider saw the body of a woman pinned to the door of a house by a sword driven through her chest. The body was naked and the breasts had been cut off."[17]

Much of the wartime publishing in Britain was in fact aimed at attracting American support.[18] A 1929 article in the The Nation asserted: "In 1916 the Allies were putting forth every possible atrocity story to win neutral sympathy and American support. We were fed every day [...] stories of Belgian children whose hands were cut off, the Canadian soldier who was crucified to a barn door, the nurses whose breasts were cut off, the German habit of distilling glycerine and fat from their dead in order to obtain lubricants; and all the rest."[18]

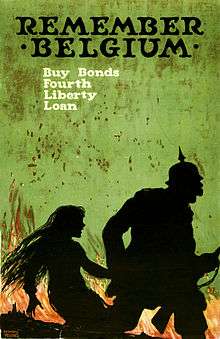

The fourth Liberty bond drive of 1918 employed a "Remember Belgium" poster depicting the silhouette of a young Belgian girl being dragged by a German soldier on the background of a burning village; historian Kimberly Jensen interprets this imagery as "They are alone in the night, and rape seems imminent. The poster demonstrates that leaders drew on the American public's knowledge of and assumptions about the use of rape in the German invasion of Belgium."[19]

In his book Roosevelt and Hitler, Robert E. Herzstein stated that "The Germans could not seem to find a way to counteract powerful British propaganda about the 'Rape of Belgium' and other alleged atrocities".[20] About the legacy of the propaganda, Gullace commented that "one of the tragedies of the British effort to manufacture truth is the way authentic suffering was rendered suspect by fabricated tales".[14]:32

Aftermath

Later analysis

In the 1920s, the war crimes of August 1914 were often dismissed as British propaganda. In recent years scholars have examined the original documents and found that large-scale atrocities were committed, and that the fabrications were incidental to the truth.[5]:162 There is a debate between those who believe the German army acted primarily out of paranoia and those (including Lipkes) who emphasize additional causes.

According to Larry Zuckerman, the German occupation far exceeded the constraints international law imposed on an occupying power. A heavy-handed German military administration sought to regulate every detail of daily life, both on a personal level with travel restraints and collective punishment, and on the economic level by harnessing the Belgian industry to German advantage and by levying repetitive massive indemnities on the Belgian provinces.[2] Before the war Belgium was the sixth largest economy in the world, but the Germans destroyed the Belgian economy so thoroughly, by dismantling industries and transporting the equipment and machinery to Germany, that it never regained its pre-war level. More than 100,000 Belgian workers were forcibly deported to Germany to work in the war economy, and to Northern France to build roads and other military facilities to the German army.[2]

Historical studies

In-depth historical studies on this subject include:

- The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I by Larry Zuckerman

- Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 by Jeff Lipkes

- German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial by John Horne and Alan Kramer.[21]

Horne and Kramer give many explanations; firstly (but not only), the collective fear of the People's War:

The source of the collective fantasy of the People's War and of the harsh reprisals with which the German army (up to its highest level) responded are to be found in the memory of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1, when the German armies faced irregular Republican soldiers (or francs-tireurs), and in the way in which the spectre of civilian involvement in warfare conjured up the worst fears of democratic and revolutionary disorder for a conservative officer corps.[22]

inexperience leading to lack of discipline amongst German soldiers, drunkenness; 'friendly fire' incidents arising from panic; frequent collisions with Belgian and French rearguards leading to confusion; rage at the stubborn and at first successful defence of Liège during the Battle of Liège, when Germany's invasion firstly failed; rage at Belgian resistance at all, not seen as a people entitled to defend themselves; prevailing almost hatred of the Roman Catholic clergy in Belgium and France; ambiguous or inadequate German field service regulations regarding civilians; failure of German logistics later leading to uncontrolled looting etc.[23]

Legacy

A ceremony took place on 6 May 2001, in Dinant. Walter Kolbow, a high secretary at the Ministry of Defence of the Federal Republic of Germany, placed a wreath and bowed before a monument to the victims bearing the inscription: To the 674 Dinantais martyrs, innocent victims of German barbarism.[24][25]

See also

- Freikorps in the Baltic

- Herero and Namaqua Genocide (1904–1907)—an earlier atrocity in German South-West Africa

- Leipzig War Crimes Trials

Notes

References

- ↑ It was described as such in the following books:

- John Horne (2010). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley and Sons. p. 265. ISBN 978-1-4051-2386-0.

- Susan R. Grayzel (2002). Women and the First World War. Longman. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-582-41876-9.

- Nicoletta Gullace (2002). The blood of our sons: men, women, and the renegotiation of British citizenship during the Great War. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-312-29446-5.

- Kimberly Jensen (2008). Mobilizing Minerva: American women in the First World War. University of Illinois Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-252-07496-7.

- Thomas F. Schneider (2007). "Huns" vs. "Corned beef": representations of the other in American and German literature and film on World War I. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-89971-385-5.

- Annette F. Timm; Joshua A. Sanborn (2007). Gender, sex and the shaping of modern Europe: a history from the French Revolution to the present day. Berg. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-84520-357-3.

- Joseph R. Conlin (2008). The American Past. Cengage Learning. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-495-56622-9.

- 1 2 3 Zuckerman, Larry (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9704-4.

- ↑ Memoirs of Prince Von Bulow: The World War and Germany's Collapse 1909–1919, translated by Geoffrey Dunlop and F. A. Voight, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1932:

There is no doubt that our invasion of Belgium, with violation it entailed of that country's sovereign neutrality, and of treaties we ourselves had signed, and the world had respected for a century, was an act of the gravest political significance. Bad was made worse when than ever by Bethmans Hollweg's speech in the Reichstag (August 4, 1914). Never perhaps, has any other statesman at the head of a great and civilized people (...) pronounced (...) a more terrible speech. Before the whole world—before his country, this spokesman of the German Government—not of the Belgian!—not of the French!—declared that, in invading Belgium we did wrong, but that necessity knows no law (...) I was aware, with this one categorical statement, we had forfeited, at a blow, the imponderabilia; that this unbelievably stupid oration would set the whole world against Germany. And on the very evening after he made it this Chancellor of the German Empire, in a talk with Sir Edward Goschen, the British Ambassador, referred to the international obligations on which Belgium relied for her neutrality as "un chiffon de papier", "a scrap of paper"...

- 1 2 Annuaire statistique de la Belgique et du Congo Belge 1915–1919. Bruxelles. 1922 p.100

- 1 2 3 4 Lipkes J. (2007) Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914, Leuven University Press

- ↑ Horne & Kramer, German atrocities, Chapter I, Third Army and Dinant

- 1 2 Beckett, I.F.W. (ed., 1988) The Roots of Counter-Insurgency, Blandford Press, London. ISBN 0-7137-1922-2

- ↑ John N. Horne & Alan Kramer (2001) German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial, Yale University Press, New Haven, Appendix I, German Atrocities in 1914 (from 5 August to 21 October and from Berneau (Province of Liège) to Esen (Province of West Flanders)), ISBN 978-0-300-08975-2

- ↑ Alan Kramer (2007) Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War Oxford University Press, pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-19-280342-9

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, P. M. R. (2005) World War I: Encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO/Greenwood, p.714

- ↑ Leuven University, p. 31: "The university colleges were closed on 9 November 1797, and all items of use, with all the books, were requisitioned for the new École Centrale, in Brussels"

- ↑ B.Tuchman, The Guns of August, pp.340-356

- ↑ Commission d'Enquete (1922) Rapports et Documents d'Enquete, vol. 1, book 1. pp. 679–704, vol. 1, book 2, pp. 605–615.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Nicoletta Gullace (2002). The Blood of Our Sons: Men, Women, and the Renegotiation of British Citizenship during the Great War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-29446-5.

- ↑ Cynthia Wachtell (2007). "Representations of German Soldiers in American World War I Literature". In Thomas F. Schneider. "Huns" vs. "Corned Beef": Representations of the Other in American and German Literature and Film on World War I. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-89971-385-5.

- ↑ Books.google.com, Slater, Tom, Dixey, Marsh and Halperin, James L, Political and Americana Memorabilia Auction, Heritage Auctions, Inc, 2005. p. 317. ISBN 978-1-59967-012-6, Poster is by Ellsworth Young

- ↑ Cynthia Wachtell (2007). "Representations of German Soldiers in American World War I Literature". In Thomas F. Schneider. "Huns" vs. "Corned Beef": Representations of the Other in American and German Literature and Film on World War I. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-89971-385-5.

- 1 2 Cynthia Wachtell (2007). "Representations of German Soldiers in American World War I Literature". In Thomas F. Schneider. "Huns" vs. "Corned Beef": Representations of the Other in American and German Literature and Film on World War I. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-89971-385-5.

- ↑ Kimberly Jensen (2008). Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War. University of Illinois Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-252-07496-7.

- ↑ "Herzstein, Robert E., Roosevelt & Hitler, p. 8

- ↑ See Summary of book

- ↑ John Horne, German war crimes

- ↑ Horne, John; Kramer, Alan (2001). "Notes on German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial". Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08975-9. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Clive Emsley, War, Culture and Memory, The Open University, Milton Keynes, 2003, p. 28. ISBN 0-7492-9611-9

- ↑ Osborn, Andrew (11 May 2001). "Belgians want money after German war apology". The Guardian. London.

Further reading

Books

- Albertini, Luigi (2005) [1957]. Origins of the War. 3 vols. New York: Enigma Books.

- Beckett, I.F.W. (1988). The Roots of Counter-Insurgency. London: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1922-2.

- Bryce, J. B. (1915). Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages appointed by His Britannic Majesty's Government and Presided over by the Right Hon. Viscount Bryce (PDF). London: HMSO. OCLC 810710978. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Fischer, Fritz (1967). The War Aims of Germany in the First World War. New York. pp. 67, 103, 170, 192–5, 215–224, 283.

- Horne, John N.; Kramer, Alan (2001). German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. Yale University Press.

- Hull, Isabel V. (2014). A scrap of paper: breaking and making international law during the Great War. Cornell University Press.

- Lipkes, Jeff (2007). Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914. Leuven University Press.

- Scheipers, Sibylle (2015). Unlawful Combatants: A Genealogy of the Irregular Fighter. Oxford University Press.

- Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim (2014) [1962]. The Guns of August. Penguin (paperbacks).

- Zuckerman, Larry (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9704-4.

Journals

- Green, Leanne (2014). "Advertising war: Picturing Belgium in First World War publicity". Media, War & Conflict. 7#3: pp: 309–325.

- Horne, J.; Kramer, A. (1994). "German 'Atrocities' and Franco-German Opinion, 1914: The Evidence of German Soldiers' Diaries". Journal of Modern History. 66 (1): 1–33. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 2124390.

- Jones, Heather (2014). "The Great War: How 1914–18 Changed the Relationship between War and Civilians". The RUSI Journal. 159#4: pp: 84–91.

- Nelson, Robert L. (2004). "Ordinary Men in the First World War? German Soldiers as Victims and Participants". Journal of Contemporary History. 39#3: pp. 425–435. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 3180736.

- Wilson, Trevor (1979). "Lord Bryce's Investigation into Alleged German Atrocities in Belgium, 1914–1915". Journal of Contemporary History. 14#3: pp. 369–383. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 10.2307/260012. sees the Bryce report as exaggerated propaganda

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rape of Belgium. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- H-Net Review of Horne & Kramer, The German Atrocities of 1914: A History of Denial

- H-Net Review of L. Zuckerman, The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I

- HistoryOfWar.org Review of J. Lipkes, Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914

- H-Net Review of J. Lipkes Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 by Jeffrey Smith

- H-Net Review of J. Lipkes. Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 by Robby Van Eetvelde

- Prof. John Horne, German War Crimes