Aftermath of World War I

World War I also had the effect of bringing political transformation to most of the principal parties involved in the conflict, transforming them into electoral democracies by bringing near-universal suffrage for the first time in history, such as Germany (German federal election, 1919), the United Kingdom (United Kingdom general election, 1918), and Turkey (Turkish general election, 1923).

_(RA)_-_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors%2C_Versailles%2C_28th_June_1919_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Blockade of Germany

Through the period from the armistice on 11 November 1918 until the signing of the peace treaty with Germany on 28 June 1919, the Allies maintained the naval blockade of Germany that had begun during the war. As Germany was dependent on imports, it is estimated that 523,000 civilians had lost their lives.[1] N. P. Howard, of the University of Sheffield, claims that a further quarter of a million more died from disease or starvation in the eight-month period following the conclusion of the conflict.[2] The continuation of the blockade after the fighting ended, as author Robert Leckie wrote in Delivered From Evil, did much to "torment the Germans ... driving them with the fury of despair into the arms of the devil." The terms of the Armistice did allow food to be shipped into Germany, but the Allies required that Germany provide the means (the shipping) to do so. The German government was required to use its gold reserves, being unable to secure a loan from the United States.

Historian Sally Marks claims that while "Allied warships remained in place against a possible resumption of hostilities, the Allies offered food and medicine after the armistice, but Germany refused to allow its ships to carry supplies". Further, Marks states that despite the problems facing the Allies, from the German government, "Allied food shipments arrived in Allied ships before the charge made at Versailles".[3] This position is also supported by Elisabeth Gläser who notes that an Allied task force, to help feed the German population, was established in early 1919 and that by May 1919 " Germany [had] became the chief recipient of American and Allied food shipments". Gläser further claims that during the early months of 1919, while the main relief effort was being planned, France provided food shipments to Bavaria and the Rhineland. She further claims that the German government delayed the relief effort by refusing to surrender their merchant fleet to the Allies. Finally, she concludes that "the very success of the relief effort had in effect deprived the [Allies] of a credible threat to induce Germany to sign the Treaty of Versailles.[4] However, it is also the case that for eight months following the end of hostilities, the blockade was continually in place, with some estimates that a further 100,000 casualties among German civilians to starvation were caused, on top of the hundreds of thousands which already had occurred. Food shipments, furthermore, had been entirely dependent on Allied goodwill, causing at least in part the post-hostilities irregularity.[5][6]

Treaty of Versailles

After the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919, between Germany on the one side and France, Italy, Britain and other minor allied powers on the other, officially ended war between those countries. Other treaties ended the belligerent relationships of the United States and the other Central Powers. Included in the 440 articles of the Treaty of Versailles were the demands that Germany officially accept responsibility for starting the war and pay economic reparations. The treaty drastically limited the German military machine: German troops were reduced to 100,000 and the country was prevented from processing major military armaments such as tanks, warships and submarines.

Influenza epidemic

Historians continue to argue about the impact the 1918 flu pandemic had on the outcome of the war. It has been posited that the Central Powers may have been exposed to the viral wave before the Allies. The resulting casualties having greater effect, having been incurred during the war, as opposed to the allies who suffered the brunt of the pandemic after the Armistice. When the extent of the epidemic was realized, the respective censorship programs of the Allies and Central Powers limited the public's knowledge regarding the true extent of the disease. Because Spain was neutral, their media was free to report on the Flu, giving the impression that it began there. This misunderstanding led to contemporary reports naming it the "Spanish flu." Investigative work by a British team led by virologist John Oxford of St Bartholomew's Hospital and the Royal London Hospital, identified a major troop staging and hospital camp in Étaples, France as almost certainly being the center of the 1918 flu pandemic. A significant precursor virus was harbored in birds, and mutated to pigs that were kept near the front.[7] The exact number of deaths is unknown but about 50 million people are estimated to have died from the influenza outbreak worldwide.[8][9] In 2005, a study found that, "The 1918 virus strain developed in birds and was similar to the 'bird flu' that today has spurred fears of another worldwide pandemic, yet proved to be a normal treatable virus that did not produce a heavy impact on the world's health."[10]

Economic and geopolitical consequences

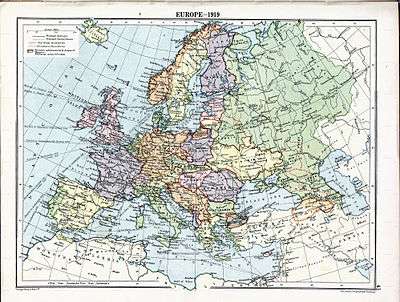

The dissolution of the German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and (earlier) Ottoman empires created a large number of new small countries in eastern Europe. Internally these new countries tended to have substantial ethnic minorities, which wished to unite with neighboring states where their ethnicity dominated. For example, Czechoslovakia had Germans, Poles, Ruthenians and Ukrainians, Slovaks and Hungarians. The League of Nations sponsored various Minority Treaties in an attempt to deal with the problem, but with the decline of the League in the 1930s, these treaties became increasingly unenforceable. One consequence of the massive redrawing of borders and the political changes in the aftermath of World War I was the large number of European refugees. These and the refugees of the Russian Civil War led to the creation of the Nansen passport.

Ethnic minorities made the location of the frontiers generally unstable. Where the frontiers have remained unchanged since 1918, there has often been the expulsion of an ethnic group, such as the Sudeten Germans. Economic and military cooperation amongst these small states was minimal, ensuring that the defeated powers of Germany and the Soviet Union retained a latent capacity to dominate the region. In the immediate aftermath of the war, defeat drove cooperation between Germany and the Soviet Union but ultimately these two powers would compete to dominate eastern Europe.

Revolutions

Perhaps the single most important event precipitated by the privations of World War I was the Russian Revolution of 1917. A socialist and often explicitly Communist revolutionary wave occurred in many other European countries from 1917 onwards, notably in Germany and Hungary.

Due to the Russian Provisional Government's failure to cede territory, German and Austrian forces defeated the Russian armies, and the new communist government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. In that treaty, Russia renounced all claims to Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and the territory of Congress Poland, and it was left to Germany and Austria-Hungary "to determine the future status of these territories in agreement with their population." Later on, Vladimir Lenin's government also renounced the Partition of Poland treaty, making it possible for Poland to claim its 1772 borders. However, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was rendered obsolete when Germany was defeated later in 1918, leaving the status of much of eastern Europe in an uncertain position.

Germany

In Germany, there was a socialist revolution which led to the brief establishment of a number of communist political systems in (mainly urban) parts of the country, the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the creation of the Weimar Republic.

On 28 June 1919 the Weimar Republic was forced, under threat of continued Allied advance, to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Germany viewed the one-sided treaty as a humiliation and as blaming it for the entire war. While this was not the intent of the treaty, the notion took root in German society and was never accepted by nationalists, although it was argued by some, such as German historian Fritz Fischer. The German government disseminated propaganda to further promote this idea, and funded the Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War to this end.

132 billion gold marks ($31.5 billion, 6.6 billion pounds) were demanded from Germany in reparations, of which only 50 billion had to be paid. In order to finance the purchases of foreign currency required to pay off the reparations, the new German republic printed tremendous amounts of money – to disastrous effect. Hyperinflation plagued Germany between 1921 and 1923. In this period the worth of fiat Papiermarks with respect to the earlier commodity Goldmarks was reduced to one trillionth (one million millionth) of its value.[11] In December 1922 the Reparations Commission declared Germany in default, and on 11 January 1923 French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr until 1925.

The treaty required Germany to permanently reduce the size of its army to 100,000 men, and destroy their tanks, air force, and U-boat fleet (her capital ships, moored in Scapa Flow, were scuttled by their crews to prevent them from falling into Allied hands).

Germany saw relatively small amounts of territory transferred to Denmark, Czechoslovakia, and Belgium, a larger amount to France (including the temporary French occupation of the Rhineland) and the greatest portion as part of a reestablished Poland. Germany's overseas colonies were divided between a number of Allied countries, most notably the United Kingdom in Africa, but it was the loss of the territory that composed the newly independent Polish state, including the German city of Danzig and the separation of East Prussia from the rest of Germany, that caused the greatest outrage. Nazi propaganda would feed on a general German view that the treaty was unfair – many Germans never accepted the treaty as legitimate, and lent their political support to Adolf Hitler.

Russian Empire

The Soviet Union benefited from Germany's loss, as one of the first terms of the armistice was the abrogation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. At the time of the armistice Russia was in the grips of a civil war which left more than seven million people dead and large areas of the country devastated. The nation as a whole suffered socially and economically. As to her border territories, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia gained independence. They were occupied again by the Soviet Union in 1940. Finland gained a lasting independence, though she repeatedly had to fight the Soviet Union for her borders. Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan were established as independent states in the Caucasus region. These countries were proclaimed as Soviet Republics in 1922 and over time were absorbed into the Soviet Union. During the war, however, Turkey captured the Armenian territory around Artvin, Kars, and Igdir, and these territorial losses became permanent. Romania gained Bessarabia from Russia. The Russian concession in Tianjin was occupied by the Chinese in 1920; in 1924 the Soviet Union renounced its claims to the district.

Austria-Hungary

With the war having turned decisively against the Central Powers, the people of Austria-Hungary lost faith in their allied countries, and even before the armistice in November, radical nationalism had already led to several declarations of independence in south-central Europe after November 1918. As the central government had ceased to operate in vast areas, these regions found themselves without a government and many new groups attempted to fill the void. During this same period, the population was facing food shortages and was, for the most part, demoralized by the losses incurred during the war. Various political parties, ranging from ardent nationalists, to social democrats, to communists attempted to set up governments in the names of the different nationalities. In other areas, existing nation states such as Romania engaged regions that they considered to be theirs. These moves created de facto governments that complicated life for diplomats, idealists, and the Western allies.

The Western forces were officially supposed to occupy the old Empire, but rarely had enough troops to do so effectively. They had to deal with local authorities who had their own agenda to fulfill. At the peace conference in Paris the diplomats had to reconcile these authorities with the competing demands of the nationalists who had turned to them for help during the war, the strategic or political desires of the Western allies themselves, and other agendas such as a desire to implement the spirit of the Fourteen Points.

For example, in order to live up to the ideal of self-determination laid out in the Fourteen Points, Germans, whether Austrian or German, should be able to decide their own future and government. However, the French especially were concerned that an expanded Germany would be a huge security risk. Further complicating the situation, delegations such as the Czechs and Slovenians made strong claims on some German-speaking territories.

The result was treaties that compromised many ideals, offended many allies, and set up an entirely new order in the area. Many people hoped that the new nation states would allow for a new era of prosperity and peace in the region, free from the bitter quarrelling between nationalities that had marked the preceding fifty years. This hope proved far too optimistic. Changes in territorial configuration after World War I included:

- Establishment of the Republic of German Austria and the Hungarian Democratic Republic, disavowing any continuity with the empire and exiling the Habsburg family in perpetuity.

- Borders of newly independent Hungary did not include two-thirds of the lands of the former Kingdom of Hungary, including large areas where the ethnic Magyars were in a majority. The new republic of Austria maintained control over most of the predominantly German-controlled areas, but lost various other German majority lands in what was the Austrian Empire.

- Bohemia, Moravia, Opava Silesia and the western part of the Duchy of Cieszyn, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia formed the new Czechoslovakia.

- Galicia, the eastern part of the Duchy of Cieszyn, northern County of Orava and northern Spisz were transferred to Poland.

- the Southern half of the County of Tyrol and Trieste were granted to Italy.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Slovenia, and Vojvodina were joined with Serbia to form the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later Yugoslavia.

- Transylvania and Bukovina became parts of Romania.

- The Austro-Hungarian concession in Tianjin was ceded to the Republic of China.

These changes were recognized in, but not caused by, the Treaty of Versailles. They were subsequently further elaborated in the Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Trianon.

The new states of eastern Europe mostly all had large national minorities. Millions of Germans found themselves in the newly created countries as minorities. More than two million ethnic Hungarians found themselves living outside of Hungary in Slovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia. Many of these national minorities found themselves in bad situations because the modern governments were intent on defining the national character of the countries, often at the expense of the other nationalities.

The interwar years were hard for the Jews of the region. Most nationalists distrusted them because they were not fully integrated into 'national communities'. In contrast to times under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, Jews were often ostracized and discriminated against. Although antisemitism had been widespread during Habsburg rule, Jews faced no official discrimination because they were, for the most part, ardent supporters of the multi-national state and the monarchy. Jews had feared the rise of ardent nationalism and nation states, because they foresaw the difficulties that would arise.

The economic disruption of the war and the end of the Austro-Hungarian customs union created great hardship in many areas. Although many states were set up as democracies after the war, one by one, with the exception of Czechoslovakia, they reverted to some form of authoritarian rule. Many quarreled amongst themselves but were too weak to compete effectively. Later, when Germany rearmed, the nation states of south-central Europe were unable to resist its attacks, and fell under German domination to a much greater extent than had ever existed in Austria-Hungary.

Ottoman Empire

At the end of the war, the Allies occupied Constantinople (İstanbul) and the Ottoman government collapsed. The Treaty of Sèvres, a plan designed by the Allies to dismember the remaining Ottoman territories, was signed on 10 August 1920, although it was never ratified by the Sultan.

The occupation of Smyrna by Greece on 18 May 1919 triggered a nationalist movement to rescind the terms of the treaty. Turkish revolutionaries led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a successful Ottoman commander, rejected the terms enforced at Sèvres and under the guise of General Inspector of the Ottoman Army, left Istanbul for Samsun to organize the remaining Ottoman forces to resist the terms of the treaty. On the eastern front, the Turkish–Armenian War and signing of the Treaty of Kars with the Russian S.F.S.R. took over territory lost to Armenia and post-Imperial Russia.[12]

On the western front, the growing strength of the Turkish nationalist forces led Greece, with the backing of Britain, to invade deep into Anatolia in an attempt to deal a blow to the revolutionaries. At the Battle of Dumlupınar, the Greek army was defeated and forced into retreat, leading to the burning of Smyrna and the withdrawal of Greece from Asia Minor. With the nationalists empowered, the army marched on to reclaim Istanbul, resulting in the Chanak Crisis in which the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was forced to resign. After Turkish resistance gained control over Anatolia and Istanbul, the Sèvres treaty was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne which formally ended all hostilities and led to the creation of the modern Turkish Republic. As a result, Turkey became the only power of World War I to overturn the terms of its defeat, and negotiate with the Allies as an equal.[13]

Lausanne Treaty formally acknowledged the new League of Nations mandates in the Middle East, the cession of their territories on the Arabian Peninsula, and British sovereignty over Cyprus. The League of Nations granted Class A mandates for the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon and British Mandate of Mesopotamia and Palestine, the latter comprising two autonomous regions: Mandate Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan). Parts of the Ottoman Empire on the Arabian Peninsula became part of what is today Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire became a pivotal milestone in the creation of the modern Middle East, the result of which bore witness to the creation of new conflicts and hostilities in the region.[14]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, funding the war had a severe economic cost. From being the world's largest overseas investor, it became one of its biggest debtors with interest payments forming around 40% of all government spending. Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920, while the value of the Pound Sterling (consumer expenditure [15]) fell by 61.2%. Reparations in the form of free German coal depressed local industry, precipitating the 1926 General Strike.

British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However, £250 million in new investment also took place during the war. The net financial loss was therefore approximately £300 million; less than two years investment compared to the pre-war average rate and more than replaced by 1928.[16] Material loss was "slight": the most significant being 40% of the British merchant fleet sunk by German U-boats. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and all immediately after the war.[17] The military historian Correlli Barnett has argued that "in objective truth the Great War in no way inflicted crippling economic damage on Britain" but that the war "crippled the British psychologically but in no other way".[18]

Less concrete changes include the growing assertiveness of Commonwealth nations. Battles such as Gallipoli for Australia and New Zealand, and Vimy Ridge for Canada led to increased national pride and a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to Britain, leading to the growth of diplomatic autonomy in the 1920s. These battles were often decorated in propaganda in these nations as symbolic of their power during the war. Loyal dominions such as Newfoundland were deeply disillusioned by Britain's apparent disregard for their soldiers, eventually leading to the unification of Newfoundland with the Confederation of Canada. Colonies such as India and Nigeria also became increasingly assertive because of their participation in the war. The populations in these countries became increasingly aware of their own power and Britain's fragility.

In Ireland, the delay in finding a resolution to the home rule issue, partly caused by the war, as well as the 1916 Easter Rising and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for separatist radicals. This led indirectly to the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence in 1919. The creation of the Irish Free State that followed this conflict in effect represented a territorial loss for the United Kingdom that was all but equal to the loss sustained by Germany, (and furthermore, compared to Germany, a much greater loss in terms of its ratio to the country's prewar territory). Despite this, the Irish Free State remained a dominion within the British Empire.

After World War I women gained the right to vote as, during the war, they had had to fill-in for what were previously categorised as "men's jobs", thus showing the government that women were not as weak and incompetent as they thought. Also, there were several significant developments in medicine and technology as the injured had to be cared for and there were several new illnesses that medicine had to deal with.

United States

While disillusioned by the war, it having not achieved the high ideals promised by President Woodrow Wilson, American commercial interests did finance Europe's rebuilding and reparation efforts in Germany, at least until the onset of the Great Depression. American opinion on the propriety of providing aid to Germans and Austrians was split, as evidenced by an exchange of correspondence between Edgar Gott, an executive with The Boeing Company and Charles Osner, chairman of the Committee for the Relief of Destitute Women and Children in Germany and Austria. Gott argued that relief should first go to citizens of countries that had suffered at the hands of the Central Powers, while Osner made an appeal for a more universal application of humanitarian ideals.[19] The American economic influence allowed the Great Depression to start a domino effect, pulling Europe in as well.

France

Alsace-Lorraine returned to France, the region which had been ceded to Prussia after the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. At the 1919 Peace Conference, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau's aim was to ensure that Germany would not seek revenge in the following years. To this purpose, the chief commander of the Allied forces, Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, had demanded that for the future protection of France the Rhine river should now form the border between France and Germany. Based on history, he was convinced that Germany would again become a threat, and, on hearing the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that had left Germany substantially intact, he observed that "This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years."

The destruction brought upon French territory was to be indemnified by the reparations negotiated at Versailles. This financial imperative dominated France's foreign policy throughout the 1920s, leading to the 1923 Occupation of the Ruhr in order to force Germany to pay. However, Germany was unable to pay, and obtained support from the United States. Thus, the Dawes Plan was negotiated after President Raymond Poincaré's occupation of the Ruhr, and then the Young Plan in 1929.

Also extremely important in the War was the participation of French colonial troops, including the Senegalese tirailleurs, and troops from Indochina, North Africa, and Madagascar. When these soldiers returned to their homelands and continued to be treated as second class citizens, many became the nuclei of pro-independence groups.

Furthermore, under the state of war declared during the hostilities, the French economy had been somewhat centralized in order to be able to shift into a "war economy", leading to a first breach with classical liberalism.

Finally, the socialists' support of the National Union government (including Alexandre Millerand's nomination as Minister of War) marked a shift towards the French Section of the Workers' International's (SFIO) turn towards social democracy and participation in "bourgeois governments", although Léon Blum maintained a socialist rhetoric.

Italy

In 1882 Italy joined with the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire to form the Triple Alliance. However, even if relations with Berlin became very friendly, the alliance with Vienna remained purely formal, as the Italians were keen to acquire Trentino and Trieste, parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire populated by Italians.

During World War I Italy aligned with the Allies, instead of joining Germany and Austria. This could happen since the alliance formally had merely defensive prerogatives, while the Central Empires were the ones who started the offensive. With the Treaty of London, Britain secretly offered Italy Trentino and Tyrol as far as Brenner, Trieste and Istria, all the Dalmatian coast except Fiume, full ownership of Albanian Valona and a protectorate over Albania, Antalya in Turkey and a share of the Turkish and German colonial empire, in exchange for Italy siding against the Central Empires.

After the victory, Vittorio Orlando, Italy's President of the Council of Ministers, and Sidney Sonnino, its Foreign Minister, were sent as the Italian representatives to Paris with the aim of gaining the promised territories and as much other land as possible. In particular, there was an especially strong opinion about the status of Fiume, which they believed was rightly Italian due to Italian population, in agreement with Wilson's Fourteen Points, the fifth of whom read:

"A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality".

Nevertheless, by the end of the war the Allies realized they had made contradictory agreements with other Nations, especially regarding Central Europe and the Middle-East. In the meetings of the "Big Four", in which Orlando's powers of diplomacy were inhibited by his lack of English, the Great powers were only willing to offer Trentino to the Brenner, the Dalmatian port of Zara, the island of Lagosta and a couple of small German colonies. All other territories were promised to other nations and the great powers were worried about Italy's imperial ambitions; Wilson, in particular, was a staunch supporter of Yugoslav rights on Dalmatia against Italy and despite the Treaty of London which he did not recognize.[20] As a result of this, Orlando left the conference in a rage. This simply favored Britain and France, which divided among themselves the former Ottoman and German territories in Africa, without handing to Italy what they had promised in these areas.[21]

In Italy, the discontent was immense: Irredentism (see: irredentismo) claimed Fiume and Dalmatia as Italian lands; but the disappointement was widespread in all Italian society, which felt the Country had taken part in a meaningless war without getting any serious benefits. This idea of a "mutilated victory" (vittoria mutilata) was the reason which led to the Impresa di Fiume ("Fiume Exploit"). On September 12, 1919, the nationalist poet Gabriele d'Annunzio led around 2,600 troops from the Royal Italian Army (the Granatieri di Sardegna), nationalists and irredentists, into a seizure of the city, forcing the withdrawal of the inter-Allied (American, British and French) occupying forces.

This event (and D'Annunzio's persona and political choices) is generally considered the expression of a deep uneasiness which troubled Italy after the war, and which eventually led to the rise of Italian Fascism.

China

The Republic of China had been one of the Allies; during the war, it had sent thousands of labourers to France. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the Chinese delegation called for an end to Western imperialistic institutions in China, but was rebuffed. China requested at least the formal restoration of its territory of Jiaozhou Bay, under German colonial control since 1898. But the western Allies rejected China's request, instead granting transfer to Japan of all of Germany's pre-war territory and rights in China. Subsequently, China did not sign the Treaty of Versailles, instead signing a separate peace treaty with Germany in 1921.

The Austro-Hungarian and German concessions in Tianjin were placed under the administration of the Chinese government; in 1920 they occupied the Russian area as well.

The western Allies' substantial accession to Japan's territorial ambitions at China's expense led to the May Fourth Movement in China, a social and political movement that had profound influence over subsequent Chinese history. The May Fourth Movement is often cited as the birth of Chinese nationalism, and both the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party consider the Movement to be an important period in their own histories.

Japan

Because of the treaty that Japan had signed with Great Britain in 1902, Japan was one of the Allies during the war. With British assistance, Japanese forces attacked Germany's territories in Shandong province in China, including the East Asian coaling base of the Imperial German navy. The German forces were defeated and surrendered to Japan in November 1914. The Japanese navy also succeeded in seizing several of Germany's island possessions in the Western Pacific: the Marianas, Carolines, and Marshall Islands.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan was granted all of Germany's pre-war rights in Shandong province in China (despite China also being one of the Allies during the war): outright possession of the territory of Jiaozhou Bay, and favorable commercial rights throughout the rest of the province, as well as a Mandate over the German Pacific island possessions that the Japanese navy had taken. Also, Japan was granted a permanent seat on the Council of the League of Nations. Nevertheless, the Western powers refused Japan's request for the inclusion of a "racial equality" clause as part of the Treaty of Versailles.

Territorial gains and losses

Nations that gained or regained territory or independence after World War I

Note: Countries which only briefly gained independence are not taken up in this list.

- Australia: gained control of German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago and Nauru

- Austria: split from the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Belgium

- Czechoslovakia: split from the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Danzig: semi-autonomous free city with independence from the German Empire

- Denmark

- Estonia: independence from the Russian Empire

- Finland: independence from the Russian Empire

- France

- Greece

- Hungary: split from the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Ireland: independence from the United Kingdom (but still part of the British Empire)

- Italy

- Japan

- Latvia: independence from the Russian Empire

- Lithuania: independence from the Russian Empire

- New Zealand: gained control of German Samoa

- Poland: recreated from parts of the Austro-Hungarian, German, and Russian Empires

- Romania

- South Africa: gained control of South West Africa

- United Kingdom: gained League of Nations Mandates in Africa and the Middle East

- Yugoslavia, as the successor state of the Kingdom of Serbia

Nations that lost territory or independence after World War I

- Austria, as the successor state of Cisleithania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Bulgaria: lost Western Thrace to Greece

- China: lost Jiaozhou Bay and most of Shandong to the Empire of Japan

- Germany, as the successor state of the German Empire

- Hungary, as the successor state of Transleithania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Montenegro declared union with Serbia and subsequently became incorporated into Yugoslavia

- Russian SFSR, as the successor state of the Russian Empire

- Turkey, as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire

- United Kingdom: lost most of Ireland as the Irish Free State, Egypt in 1922

Social trauma

The experiences of the war in the west are commonly assumed to have led to a sort of collective national trauma afterward for all of the participating countries. The optimism of 1900 was entirely gone and those who fought became what is known as "the Lost Generation" because they never fully recovered from their suffering. For the next few years, much of Europe mourned privately and publicly; memorials were erected in thousands of villages and towns.

So many British men of marriageable age died or were injured that the students of one girls' school were warned that only 10% would marry.[22][23]:20,245 The 1921 United Kingdom Census found 19,803,022 women and 18,082,220 men in England and Wales, a difference of 1.72 million which newspapers called the "Surplus Two Million".[23]:22–23 In the 1921 census there were 1,209 single women aged 25 to 29 for every 1,000 men. In 1931 50% were still single, and 35% of them did not marry while still able to bear children.[22]

As early as 1923, Stanley Baldwin recognized a new strategic reality that faced Britain in a disarmament speech. Poison gas and the aerial bombing of civilians were new developments of the First World War. The British civilian population did not, for centuries, have any serious reason to fear invasion. So the new threat of poison gas dropped from enemy bombers excited a grossly exaggerated view of the civilian deaths that would occur on the outbreak of any future war. Baldwin expressed this in his statement that "The bomber will always get through". The traditional British policy of a balance of power in Europe no longer safeguarded the British home population. Out of this fear came appeasement. It is notable that neither Baldwin nor Neville Chamberlain fought in the war, but the anti-appeasers Antony Eden, Harold Macmillan and Winston Churchill did.

One gruesome reminder of the sacrifices of the generation was the fact that this was one of the first times in conflict whereby more men died in battle than from disease, which was the main cause of deaths in most previous wars. The Russo-Japanese War was the first conflict where battle deaths outnumbered disease deaths, but it was fought on a much smaller scale between just two nations.

This social trauma made itself manifest in many different ways. Some people were revolted by nationalism and what it had caused, so they began to work toward a more internationalist world through organizations such as the League of Nations. Pacifism became increasingly popular. Others had the opposite reaction, feeling that only military strength could be relied upon for protection in a chaotic and inhumane world that did not respect hypothetical notions of civilization. Certainly a sense of disillusionment and cynicism became pronounced. Nihilism grew in popularity. Many people believed that the war heralded the end of the world as they had known it, including the collapse of capitalism and imperialism. Communist and socialist movements around the world drew strength from this theory, enjoying a level of popularity they had never known before. These feelings were most pronounced in areas directly or particularly harshly affected by the war, such as central Europe, Russia and France.

Artists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, Ernst Barlach, and Käthe Kollwitz represented their experiences, or those of their society, in blunt paintings and sculpture. Similarly, authors such as Erich Maria Remarque wrote grim novels detailing their experiences. These works had a strong impact on society, causing a great deal of controversy and highlighting conflicting interpretations of the war. In Germany, nationalists including the Nazis believed that much of this work was degenerate and undermined the cohesion of society as well as dishonoring the dead.

Remains of ammunition

Throughout the areas where trenches and fighting lines were located, such as the Champagne region of France, quantities of unexploded ordnance have remained, some of which remains dangerous, continuing to cause injuries and occasional fatalities in the 21st century. Some are found by farmers ploughing their fields and have been called the iron harvest. Some of this ammunition contains toxic chemical products such as mustard gas. Cleanup of major battlefields is a continuing task with no end in sight for decades to come. Squads remove, defuse or destroy hundreds of tons of unexploded ammunition every year in Belgium, France, and Germany.

Memorials

War memorials

Many towns in the participating countries have war memorials dedicated to local residents who lost their lives. Examples include:

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia

- Liberty Memorial, Kansas City, Missouri, United States

- District of Columbia War Memorial, Washington, DC, United States

- Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial

- The Cenotaph, London, United Kingdom

- Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres, Belgium

- Thiepval Memorial

- Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing at Passchendaele

- Verdun Memorial Museum

- Vimy Ridge Memorial, Vimy, France

- Gallipoli Memorial, Turkey

- Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne, Australia

- Irish National War Memorial Gardens, Dublin, Ireland

- Island of Ireland Peace Park, Messines, Belgium

- National War Memorial, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- National War Memorial, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada

- Kriegerdenkmal auf dem Neroberg,[24] Wiesbaden, Hessen, Germany

- Sacrario militare di Redipuglia, Fogliano Redipuglia, Italy

Tombs of Unknown Soldiers

- Monument to the Unknown Hero, Belgrade, Serbia

- Amar Jawan Jyoti, New Delhi, India

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Arc de Triomphe, Paris, France

- The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, London, United Kingdom

- Tomb of the Unknowns, Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, United States

- Tomba del milite ignoto, Rome, Italy

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia

- New Zealand Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, Wellington, New Zealand

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Syntagma Square, Athens, Greece

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Bucharest, Romania

Television documentaries

The first major television documentary on the history of the war was the BBC's The Great War (1964), made in association with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the Imperial War Museum. The series consists of 26 forty-minute episodes featuring extensive use of archive footage gathered from around the world and eyewitness interviews. Although some of the programme's conclusions have been disputed by historians it still makes compelling and often moving viewing.

Other television documentaries of note on the conflict include World War One (1964) by CBS; The First World War (2004), based on Hew Strachan's works, and The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century (1996), shown on PBS.

In 2014, a French television documentary titled Apocalypse la 1ère Guerre mondiale <http://apocalypse.france2.fr/premiere-guerre-mondiale/fr/home> aired given the 100th anniversary of the war's beginning. This documentary's English version appeared on American television the same year, entitled Apocalypse: World War I. <http://www.ahctv.com/tv-shows/apocalypse-wwi/about-apocalypse-wwi.htm> The documentary is five one hour parts, and features colorized film segments of old black and white footage. The documentary also emphasizes the sheer volume of casualties and carnage due to outdated military tactics.

See also

- List of people associated with World War I

- Surviving veterans of World War I

- Revolutions of 1917–23

- Aftermath of World War II

Notes

- ↑ 'german casualties'

- ↑

- ↑ Marks, Sally (1986). "1918 and After: The Postwar Era". In Martel, Gordon. The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered. Boston: Allen & Unwin. p. 19. ISBN 0-04-940084-3.

- ↑ Gläser (1998). The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment After 75 Years. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 388–391. ISBN 0-521-62132-1.

- ↑ Germany. Gesundheits-Amt. Schaedigung der deutschen Volkskraft durch die feindliche Blockade. Denkschrift des Reichsgesundheitsamtes, Dezember 1918. (Parallel English translation) Injuries inflicted to the German national strength through the enemy blockade. Memorial of the German Board of Public Health, 27 December 1918 [Berlin, Reichsdruckerei,]The report notes on page 17 that the figures for the second half of 1918 were estimated based on the first half of 1918.

- ↑ "The National Archives: The Blockade of Germany

- ↑ ^ Connor, Steve, "Flu epidemic traced to Great War transit camp", The Guardian (UK), Saturday, 8 January 2000. Accessed 2009-05-09. Archived 11 May 2009.

- ↑ NAP

- ↑ Influenza Report

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/10/1005_051005_bird_flu.html

- ↑ Table IV (page 441) of The Economics of Inflation by Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, published 1937.

- ↑ (Russian) Text of the Treaty of Kars

- ↑ Countrystudies – Turkey

- ↑ Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East 1914–1922. New York: H. Holt. p. 565. ISBN 0-8050-0857-8.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-19. Retrieved 2006-02-19.

- ↑ Taylor, A. J. P. (1976). English History, 1914–1945. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-19-821715-3.

- ↑ Taylor, A. J. P. (1976). English History, 1914–1945. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-19-821715-3.

- ↑ Barnett, Correlli (2002). The Collapse of British Power. London: Pan. pp. 424 and 426. ISBN 0-330-49181-4.

- ↑ Kuhlman, Erika A., Of Little Comfort. 2012. pp. 120–121.

- ↑ But perhaps the major hindrance to Italy's aims were the different opinions of Orlando and Sonnino: the first was decided to obtain Fiume and forsake Dalmatia, Sonnino did not mean to abandon Dalmatia and would have willingly left Fiume. This indecision proved fatal for Italy, which did not gain either of the territories.

- ↑ (Jackson, 1938)

- 1 2 Cable, Amanda (2007-09-15). "Condemned to be virgins: The two million women robbed by the war". Daily Mail. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- 1 2 Nicholson, Virginia (2008). Singled Out: How Two Million British Women Survived Without Men After the First World War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-537822-9.

- ↑ Kriegerdenkmal auf dem Neroberg

Resources

- Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War by Margaret MacMillan, John Murray ISBN 0-7195-5939-1

- Peacemaking, 1919 by Harold Nicolson ISBN 1-931541-54-X

- Hew Strachan ed.: "The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War" is a collection of chapters from various scholars that survey the War.

- The Wreck of Reparations, being the political background of the Lausanne Agreement, 1932 by Sir John Wheeler-Bennett New York, H. Fertig, 1972.

- References to 'Izmir' in 1919 changed to Smyrna, as it was named until 1930

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aftermath of World War I. |

- FirstWorldWar.com "A multimedia history of World War I"

- The war to end all wars on BBC site

- "The Heritage of the Great War"

- The British Army in the Great War