Banana republic

Banana republic or banana state is a political science term used originally for politically unstable countries in Latin America whose economies are largely dependent on exporting a limited-resource product, e.g. bananas. It typically has stratified social classes, including a large, impoverished working class and a ruling plutocracy of business, political, and military elites.[1] This politico-economic oligarchy controls the primary-sector productions to exploit the country's economy.[2]

Origin

The history of the first banana republic begins with the introduction of the banana to the US in 1870, by Lorenzo Dow Baker, captain of the schooner Telegraph. He initially bought bananas in Jamaica and sold them in Boston at a 1,000 percent profit.[3] The banana proved popular with Americans, as a nutritious tropical fruit that was less expensive than fruit grown locally in the U.S., such as apples. In 1913, for example, twenty-five cents bought a dozen bananas, but only two apples.[4] Its popularity among Americans was also spurred by the American railroad tycoons Henry Meiggs and his nephew, Minor C. Keith, who in 1873 began establishing banana plantations along the railroads they built in Costa Rica to produce food for their railroad workers. This experience led them to recognize the potential profitability of exporting bananas for sale, and they began exporting the fruit to the Southeastern United States.[5]

In the mid-1870s, to manage the new industrial-agriculture business enterprise in the countries of Central America, Keith founded the Tropical Trading and Transport Company: one-half of what would later become the United Fruit Company (Chiquita Brands International, created in 1899 by corporate merger with the Boston Fruit Company and owned by Andrew Preston). By the 1930s, the international political and economic tensions of the United Fruit Company had enabled it to gain control of 80 to 90 per cent of the U.S. banana trade.[6] Nonetheless, despite the UFC monopoly, in 1924, the Vaccaro Brothers established the Standard Fruit Company (Dole Food Company) to export Honduran bananas to the port of New Orleans in the Gulf of Mexico coast of the U.S. The fruit exporters were able to keep U.S. prices so low because the banana companies, through their manipulation of the producing countries' national land use laws, were able to cheaply buy large tracts of prime agricultural land for banana plantations in the countries of the Caribbean Basin, the Central American isthmus, and the tropical South American countries—and, having rendered the native peoples landless through a policy of legalistic dispossession, were therefore able to employ them as low-wage workers.[5]

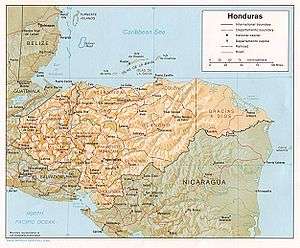

Moreover, by the late 19th century, three American multinational corporations—the United Fruit Company, the Standard Fruit Company, and the Cuyamel Fruit Company—dominated the cultivation, harvesting, and exportation of bananas, and controlled the road, rail, and port infrastructure of Honduras. In the northern coastal areas near the Caribbean Sea, the Honduran government ceded to the banana companies 500 hectares (1,235.52 acres) for each kilometre of railroad laid, even though there was still no passenger or freight railroad to Tegucigalpa, the national capital city. Among the Honduran people, the United Fruit Company was known as El Pulpo ("The Octopus"), because its influence had come to pervade their society, controlled their country's transport infrastructure, and sometimes violently manipulated national politics.[7]

Etymology

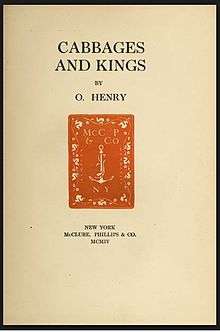

American writer O. Henry (William Sydney Porter, 1862–1910) coined "banana republic"[8] to describe the fictional Republic of Anchuria in the book Cabbages and Kings (1904),[9] a collection of thematically related short stories inspired by his experiences in Honduras where he lived only six months until January 1897, holed up in a hotel in Trujillo, when he was wanted in the United States for bank embezzlement.[10]

In political science, the term banana republic is a pejorative descriptor for a servile dictatorship that abets or supports, for kickbacks, the exploitation of large-scale plantation agriculture, especially banana cultivation.[2] More generally, it is a derogatory term for a country that is considered to have a weak economy, a dishonest or cruel government, and public services that do not work.[11] In economics, a banana republic is a country operated as a commercial enterprise for private profit, effected by a collusion between the State and favored monopolies, in which the profit derived from the private exploitation of public lands is private property, while the debts incurred thereby are a public responsibility. Such an imbalanced economy remains limited by the uneven economic development of town and country, and tends to cause the national currency to become devalued paper-money, rendering the country ineligible for international-development credit.[12]

Examples

Honduras

In the early 20th century, instrumental in establishing the "banana republic" stereotype was the US businessman Sam Zemurray, founder of the Cuyamel Fruit Company. He had entered into the banana-export business by buying overripe bananas from the United Fruit Company to sell in New Orleans. In 1910, he bought 6,070 hectares (15,000 acres) of the Caribbean coast of Honduras for agricultural exploitation by the Cuyamel Fruit Company. In 1911, Zemurray entered into a business and political alliance with Manuel Bonilla, an ex-President of Honduras (1904–07), and General Lee Christmas, an American mercenary soldier, for the purpose of unilaterally changing the republican government of Honduras.

To this end, the mercenary army of the Cuyamel Fruit Company, led by Gen. Christmas, carried out a coup d'état against President Miguel R. Dávila (1907–11) and installed General Manuel Bonilla as his successor (1912–13). The United States Government turned a blind eye to this deposition of the elected government of Honduras by a privately owned army, with the U.S. State Department seeing President Dávila as too politically liberal and a poor businessman whose management decisions had caused Honduras to become too indebted to Great Britain—an unacceptable geopolitical risk for the U.S. in light of the Monroe Doctrine. Moreover, domestically, the Dávila Government had slighted the Cuyamel Fruit Company by colluding with the rival United Fruit Company to award it a banana-trade monopoly—which it got in exchange for the fruit company's brokering of U.S. Government loans for the Honduran government.[6][13]

Because of its resulting political instability, stalled economy, and huge external debt (of about US$4 billion), the Republic of Honduras was excluded from international capital investment. Its financial deficit perpetuated its economic stagnation, and so perpetuated its banana republic image as well.[14] With the native government hobbled with a historical, inherited foreign debt, such fiscal weakness undermined the Honduran Government's functions, and so allowed foreign multinational corporations to manage the country and the people of Honduras more effectively and efficiently—especially because the fruit companies had built, and thus controlled, the Honduran infrastructure (road, rail, port); had established long-distance communications (telegraph, telephone); and so were the principal employers in the economy of Honduras. In the event, the United States dollar became the legal-tender currency of Honduras; the mercenary Gen. Lee Christmas became Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Honduras, and later was appointed U.S. Consul to the Republic of Honduras.[15] Nonetheless, 23 years later, by means of a hostile takeover, Sam Zemurray assumed control of the rival United Fruit Company, in 1933.[7]

Guatemala

Guatemala suffered the regional socio-economic legacy of the banana republic: inequitably distributed agricultural land and natural wealth, uneven economic development, and an economy dependent upon a few export crops—usually bananas, coffee and sugar cane. The inequitable land distribution was an important cause of national poverty, and the concomitant sociopolitical discontent and insurrection. Almost 90 per cent of the country's farms are too small to yield adequate subsistence harvests to the farmers, while two per cent of the country's farms occupy 65 per cent of the arable land, property of the local oligarchy.

During the 1950s, the United Fruit Company sought to convince the governments of U.S. Presidents Harry Truman (1945–53) and Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) that the popular, elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán of Guatemala was secretly pro-Soviet for having expropriated unused "fruit company lands" to landless peasants. In the Cold War (1945–91) context of the pro-active anti-communist politics exemplified by U. S. Senator Joseph McCarthy in the years 1947–57, geo-political concerns about the security of the Western Hemisphere facilitated President Eisenhower's ordering and authorizing Operation Success, the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état by means of which the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency deposed the democratically elected government (1950–54) of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán and installed the pro-business government of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas (1954–57), which lasted for three years until his assassination by a presidential guard.[2]

A mixed history of elected presidents and puppet-master military juntas were the governments of Guatemala in the course of the thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War (1960–96). However, in 1986, at the 26-year mark, the Guatemalan people promulgated a new political constitution, and elected Vinicio Cerezo (1986–91) president; then Jorge Serrano Elías (1991–93).[16]

In art

In the book Canto General (General Song, 1950), the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904–73) denounced foreign multinational corporate political dominance of Latin American countries with the four-stanza poem "La United Fruit Co."; the second-stanza excerpts read:[17]

. . . The Fruit Company, Inc.

Reserved for itself the most succulent,

The central coast of my own land,

The delicate waist of the Americas.It rechristened its territories

It established a comic opera. . . .

As the "Banana Republics",

And over the sleeping dead,

Over the restless heroes

Who brought about the greatness,

The liberty and the flags,

Gabriel García Márquez's book One Hundred Years of Solitude depicts the capitalist imperialism of the banana companies as voracious and harmful to the inhabitants of Macondo. The questionable business policies of these companies, supported by the country's government, bring corruption and brutality to Macondo and oppression to the inhabitants.

In this epic tale of magic realism, José Arcadio Segundo, the silent and solitary brother of Aureliano Segundo, has been organizing the banana plantation workers to strike in protest of the inhumane working conditions. Macondo is placed under martial law, and the workers respond by sabotaging the plantation. The government reacts by inviting more than 3,000 of the workers to gather for a meeting with the leadership of the province and to resolve their differences. The meeting is a trick, and the army surrounds the workers with machine guns and methodically kills them all. The corpses are collected onto a train and dumped into the sea. José Arcadio Segundo, taken for dead, is thrown onto the train as well, but he manages to jump off the train and walk back to Macondo. There, he is horrified to discover that all memory of the massacre has been wiped out—none of the people of Macondo remember what happened, and they refuse to believe José Arcadio Segundo when he tells them. A heavy, unrelenting rain falls on the town and does not stop, destroying any physical traces of the massacre.

Modern interpretations

Countries[18] that obtained independence from colonial powers in the 20th and 21st centuries have at times thereafter tended to share traits of banana republics due to influence of large private corporations in their politics, for example; Maldives (resort companies),[19] Chile (foreign mining companies) and the Philippines (tobacco industry, American government and corporations, and the Chinese government).[20][21]

On 14 May 1986 then Australian Treasurer Paul Keating stated that Australia might become a banana republic.[22] This has received a lot of commentary/criticism[23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] and is seen as part of a turning point in Australia's political and economic history.[32]

After the election of Donald Trump in 2016, concerns about nepotism led to questions about whether he was turning the United States into a banana republic.[33]

See also

- Absurdistan

- Dictator novel

- Dutch disease

- Failed state

- Hydraulic empire

- Kangaroo court

- McOndo

- Neo-colonialism

- Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904), by Joseph Conrad

- Rentier state

- Ruritania

- William Walker

References

- ↑ Richard Alan White (1984). The Morass. United States Intervention in Central America. New York: Harper & Row. p. 319. P. 95. ISBN 0-060-91145-X; ISBN 978-0-06091-145-4.

- 1 2 3 "Big-business Greed Killing the Banana (p. A19)". The Independent, via The New Zealand Herald. 24 May 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ Alison Acker (1988). Honduras. The Making of a Banana Republic. Toronto: Between the Lines. p. 60. ISBN 0-919-94689-5; ISBN 978-0-91994-689-7.

- ↑ Dan Koeppel (2008). Banana. The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World. London: Hudson Street Press. p. 68. ISBN 1-594-63038-0; ISBN 978-1-59463-038-5.

- 1 2 Ibid., p. 60.

- 1 2 Alison Acker (1988), p. 63.

- 1 2 Peter Chapman (2007). Bananas. How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. New York: Canongate. p. 102. ISBN 1-841-95881-6; ISBN 978-1-84195-881-1.

- ↑ Occurrences on Google Books.

- ↑ O. Henry (1904). Cabbages and Kings. New York City: Doubleday, Page & Company. pp. 132, 296.

- ↑ Malcolm D. MacLean (Summer 1968). "O. Henry in Honduras". American Literary Realism, 1870–1910. 1 (3): 36–46. JSTOR 27747601.

- ↑ Macmillian Dictionnary

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens (9 October 2008). "America the Banana Republic". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ Darío A. Euraque (1996). Reinterpreting the Banana Republic: Region and State in Honduras, 1870–1972. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-807-84604-X; ISBN 978-0-80784-604-9.

- ↑ W.S. Valentine (November 1916). "Need for Capital in Latin America: Honduras". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 68: 185–87. JSTOR 1013083.

- ↑ George Black (1988). The Good Neighbor. How the United States Wrote the History of Central America and the Caribbean. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 35. ISBN 0-394-75965-6; ISBN 978-0-39475-965-4.

- ↑ Carol A. Smith (August 1978). "Beyond Dependency Theory: National and Regional Patterns of Underdevelopment in Guatemala". American Ethnologist. 5 (3): 574–617. doi:10.1525/ae.1978.5.3.02a00090. JSTOR 643758.

- ↑ George Black (1988), p. 33.

- ↑ Corr, Anders S.; Tacujan, Priscilla A. (July 2013). "Chinese Political and Economic Influence in the Philippines: Implications for Alliances and the South China Sea Dispute". The Journal of Political Risk (pub by Corr Analytics Inc.). 1 (3). Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Maldives election chaos fuels 'banana republic' fears". Asia One News. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ Aquino, Tricia (3 February 2014). "Which public health policy in ASEAN is most susceptible to tobacco industry influence". Interaksyon. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ Philippines - Period of American influence. Encyclopædia Britannica. UK. 2014. ISBN 9781593392925.

- ↑ Wikiquote:Paul Keating

- ↑ Barton, Russell; Short, Michael (15 May 1986). "Keating gloom: $ falls". The Age. Fairfax Media.

- ↑ Cleary, Paul (17 May 1996). "What will we do when it's all been sold?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media.

- ↑ Cleary, Paul (13 June 1998). "If the economy's so good, how come the dollar's so bad?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media.

- ↑ Byrne, Patrick J. (18 December 2004). "ECONOMICS: Australia's $403 billion foreign debt: hail the banana republic!". News Weekly (2697). National Civic Council. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Garnaut, John (2 March 2005). "Worst deficit in 50 years spells banana drama". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Colebatch, Tim (15 May 2006). "20 years from Keating, what price a banana now?". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Banana republic? No, worse: like NZ". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. 13 September 2007.

- ↑ van Onselen, Leith. "Revisiting the banana republic". www.macrobusiness.com.au. Macro Associates Pty Ltd. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Jericho, Greg (1 January 2014). "Cabinet papers show Paul Keating had a 'budget emergency' of his own". The Guardian (Australia Edition). Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Crotty, Martin; Andrew Roberts, David (2009). Turning Points in Australian History (1st ed.). Sydney Australia: UNSW Press. pp. 224–238. ISBN 978-1-921410-56-7.

- ↑ Nguyen, Tina (November 21, 2016), Is Donald Trump Turning the U.S. into a Banana Republic?, Vanity Fair, retrieved November 23, 2016

External links

- From Arbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America – video report by Democracy Now!

- Cabbages and Kings –The O. Henry book of short stories wherein he coined the banana republic term

- The Banana Republic: The Myth of the United Fruit Company