Rickettsia

| Rickettsia | |

|---|---|

| |

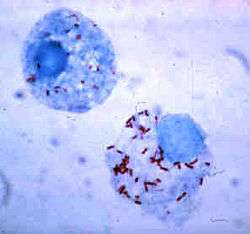

| Rickettsia rickettsii (red dots) in the cell of a deer tick | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Subclass: | Rickettsidae |

| Order: | Rickettsiales |

| Family: | Rickettsiaceae |

| Genus: | Rickettsia da Rocha-Lima, 1916 |

| Species | |

|

Rickettsea aeschlimannii[1] | |

Rickettsia is a genus of nonmotile, gram-negative, nonspore-forming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that can be present as cocci (0.1 μm in diameter), rods (1–4 μm long), or thread-like (10 μm long). The term rickettsia, named after Howard Taylor Ricketts, is often used interchangeably for any member of the Rickettsiales. Being obligate intracellular parasites, the Rickettsia survival depends on entry, growth, and replication within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic host cells (typically endothelial cells).[8] Rickettsia cannot live in artificial nutrient environments and is grown either in tissue or embryo cultures; typically, chicken embryos are used: a method developed by Ernest William Goodpasture and his colleagues at Vanderbilt University in the early 1930s.

Rickettsia species are transmitted by numerous types of arthropod, including chigger, ticks, fleas, and lice, and are associated with both human and plant disease. Most notably, Rickettsia species are the pathogen responsible for: typhus, rickettsialpox, Boutonneuse fever, African tick bite fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Flinders Island spotted fever and Queensland tick typhus (Australian tick typhus).[9] Despite the similar name, Rickettsia bacteria do not cause rickets, which is a result of vitamin D deficiency. The majority of Rickettsia bacteria are susceptible to antibiotics of the tetracycline group.

Classification

The classification of Rickettsia into three groups (spotted fever, typhus, and scrub typhus) was initially based on serology. This grouping has since been confirmed by DNA sequencing. All three of these contain human pathogens. The scrub typhus group has been reclassified as a related new genus – Orientia – but many medical textbooks still list this group under the rickettsial diseases.

Rickettsia are more widespread than previously believed and are known to be associated with arthropods, leeches, and protists. Divisions have also been identified in the spotted fever group and this group likely should be divided into two clades.[10] Arthropod-inhabiting rickettsiae are generally associated with reproductive manipulation (such as parthenogenesis) to persist in host lineage [11]

In March 2010, Swedish researchers reported a case of bacterial meningitis in a woman caused by Rickettsia helvetica previously thought to be harmless.[12]

| Phylogeny of Rickettsiales | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robust 16S + 23S phylogeny of Rickettsidae from Ferla et al. (2013)[13] |

Spotted fever group

- Rickettsia rickettsii (Western Hemisphere)

- Rickettsia akari (USA, former Soviet Union)

- Rickettsia conorii (Mediterranean countries, Africa, Southwest Asia, India)

- Rickettsia sibirica (Siberia, Mongolia, northern China)

- Rickettsia australis (Australia)

- Rickettsia felis (North and South America, Southern Europe, Australia)

- Rickettsia africae (South Africa)

- Rickettsia hoogstraalii (Croatia, Spain and Georgia USA)[14]

- Unknown pathogenicity

Typhus group

- Rickettsia prowazekii (worldwide)

- Epidemic typhus, recrudescent typhus, and sporadic typhus

- Rickettsia typhi (worldwide)

- Murine typhus (endemic typhus)

Scrub typhus group

- The causative agent of scrub typhus formerly known as R. tsutsugamushi has been reclassified into the genus Orientia.

Flora and fauna pathogenesis

Plant diseases have been associated with these Rickettsia-like organisms (RLOs):[15]

- Beet latent rosette RLO

- Citrus greening bacterium possibly this citrus greening disease

- Clover leaf RLO

- Grapevine infectious necrosis RLO

- Grapevine Pierce's RLO

- Grapevine yellows RLO

- Witch's broom disease on Larix spp.

- Peach phony RLO

- Papaya Bunchy Top Disease [16]

Infection occurs in nonhuman mammals; for example, species of Rickettsia have been found to afflict the South American guanaco, Lama guanacoe.[17]

Pathophysiology

Genomics

Certain segments of rickettsial genomes resemble those of mitochondria.[18] The deciphered genome of R. prowazekii is 1,111,523 bp long and contains 834 genes.[19] Unlike free-living bacteria, it contains no genes for anaerobic glycolysis or genes involved in the biosynthesis and regulation of amino acids and nucleosides. In this regard, it is similar to mitochondrial genomes; in both cases, nuclear (host) resources are used.

ATP production in Rickettsia is the same as that in mitochondria. In fact, of all the microbes known, the Rickettsia is probably the closest relative (in a phylogenetic sense) to the mitochondria. Unlike the latter, the genome of R. prowazekii, however, contains a complete set of genes encoding for the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the respiratory chain complex. Still, the genomes of the Rickettsia, as well as the mitochondria, are frequently said to be "small, highly derived products of several types of reductive evolution".

The recent discovery of another parallel between Rickettsia and viruses may become a basis for fighting HIV infection.[20] Human immune response to the scrub typhus pathogen, Orientia tsutsugamushi, appears to provide a beneficial effect against HIV infection progress, negatively influencing the virus replication process. A probable reason for this actively studied phenomenon is a certain degree of homology between the rickettsiae and the virus – namely, common epitope(s) due to common genome fragment(s) in both pathogens. Surprisingly, the other infection reported to be likely to provide the same effect (decrease in viral load) is the virus-caused illness dengue fever.

Comparative analysis of genomic sequences have also identified five conserved signature indels in important proteins which are uniquely found in members of the genus Rickettsia. These indels consist of a four-amino-acid insertion in transcription repair coupling factor Mfd, a 10-amino-acid insertion in ribosomal protein L19, a one-amino-acid insertion in FtsZ, a one-amino-acid insertion in major sigma factor 70, and a one-amino-acid deletion in exonuclease VII. These indels are all characteristic of the genus and serve as molecular markers for Rickettsia.[21]

Naming

The genus Rickettsia is named after Howard Taylor Ricketts (1871–1910), who studied Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana, and eventually died of typhus after studying that disease in Mexico City.

References

- ↑ Beati, L.; Meskini, M., et al. (1997), "Rickettsia aeschlimannii sp. nov., a new spotted fever group rickettsia associated with Hyalomma marginatum ticks", Int J Syst Bacteriol 47 (2): 548-55s4

- ↑ Kelly P.J.; Beati L.; et al. (1996). "Rickettsia africae sp. nov., the etiological agent of African tick bite fever". Int J Syst Bacteriol. 46 (2): 611–614. doi:10.1099/00207713-46-2-611.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Skerman, VBD; McGowan, V; Sneath, PHA, eds. (1989). Approved Lists of Bacterial Names (amended ed.). Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology

- ↑ Fujita, H.; Fournier, P.-E., et al. (2006), "Rickettsia asiatica sp. nov., isolated in Japan", Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56 (Pt 10): 2365–2368

- ↑ Truper H.G.; De' Clari L. (1997). "Taxonomic note: Necessary correction of specific epithets formed as substantives (nouns) 'in apposition'" (PDF). Int J Syst Bacteriol. 47 (3): 908–909. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-3-908.

- ↑ Billings A.N.; Teltow G.J.; et al. (1998). "Molecular characterization of a novel Rickettsia species from Ixodes scapularis in Texas" (PDF). Emerg Infect Dis. 4 (2): 305–309. doi:10.3201/eid0402.980221.

- ↑ La Scola, B.; Meconi, S., et al. (2002), "Emended description of Rickettsia felis (Bouyer et al. 2001), a temperature-dependent cultured bacterium", Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52 (Pt 6): 2035–2041

- ↑ Walker DH (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Rickettsiae. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ↑ Unsworth NB, Stenos J, Graves SR, et al. (April 2007). "Flinders Island spotted fever rickettsioses caused by "marmionii" strain of Rickettsia honei, Eastern Australia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (4): 566–73. doi:10.3201/eid1304.050087. PMC 2725950

. PMID 17553271.

. PMID 17553271. - ↑ Gillespie J.J.; Beeir M.S.; Rahman M.S.; Ammerman N.C.; Shallom J.M.; Purkayastha A.; Sobral B.S.; Azad A.F. (2007). "Plasmids and rickettsial evolution: insight from 'Rickettsia felis'". PLoS ONE. 2: e266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000266.

.

. - ↑ Perlman, S.J.; Hunter, M.S.; Zchori-Fein, E. (2006). "The emerging diversity of 'Rickettsia'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2097–2106. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3541. PMC 1635513

. PMID 16901827.

. PMID 16901827. - ↑ "Rickettsia helvetica in Patient with Meningitis, Sweden, 2006" Emerging Infectious Diseases, Volume 16, Number 3 - March 2010

- ↑ Ferla, M. P.; Thrash, J. C.; Giovannoni, S. J.; Patrick, W. M. (2013). "New rRNA gene-based phylogenies of the Alphaproteobacteria provide perspective on major groups, mitochondrial ancestry and phylogenetic instability". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e83383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083383. PMC 3859672

. PMID 24349502.

. PMID 24349502. - ↑ Duh, D., V. Punda-Polic, T. Avsic-Zupanc, D. Bouyer, D.H. Walker, V.L. Popov, M. Jelovsek, M. Gracner, T. Trilar, N. Bradaric, T.J. Kurtti and J. Strus. (2010) Rickettsia hoogstraalii sp. nov., isolated from hard- and soft-bodied ticks. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 60, 977-984; http://ijs.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/60/4/977, accessed 16 July 2010.

- ↑ Smith IM, Dunez J, Lelliot RA, Phillips DH, Archer SA (1988). European Handbook of Plant Diseases. Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-01222-6.

- ↑ Davis, M. J. 1996.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Guanaco: Lama guanicoe, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Strömberg Archived 4 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Emelyanov VV (2003). "Mitochondrial connection to the origin of the eukaryotic cell". Eur J Biochem. 270 (8): 1599–618. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03499.x. PMID 12694174.

- ↑ Andersson SG, et al. (1998). "The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria". Nature. 396 (6707): 133–40. doi:10.1038/24094. PMID 9823893.

- ↑ Kannangara S, DeSimone JA, Pomerantz RJ (2005). "Attenuation of HIV-1 infection by other microbial agents". J Infect Dis. 192 (6): 1003–9. doi:10.1086/432767. PMID 16107952.

- ↑ Gupta, Radhey S. (January 2005). "Protein Signatures Distinctive of Alpha Proteobacteria and Its Subgroups and a Model for α –Proteobacterial Evolution". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 31 (2): 101–135. doi:10.1080/10408410590922393. PMID 15986834.

External links

- Rickettsia genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- African Tick Bite Fever from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Raw Living Radio Interview 3 Show Series in HD 2014 from the EarthShiftProject.com an Educational and Informational Research Organization welcoming More participation