Russo-Polish War (1654–67)

| Russo-Polish War (1654–1667) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jan Chryzostom Pasek in the Battle of Lachowicze (1660), a Juliusz Kossak painting. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Aleksey Trubetskoy, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Yurii Khmelnytsky, Vasily Sheremetev, Vasiliy Buturlin, Ivan Khovansky, Yuri Dolgorukov, Prince Yakov Cherkassky |

Stefan Czarniecki, Wincenty Gosiewski, John II Casimir, Stanisław Lanckoroński, Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski, Michał Kazimierz Pac, Aleksander Hilary Połubiński, Stanisław Rewera Potocki, Janusz Radziwiłł, Paweł Jan Sapieha, Ivan Vyhovsky, Pavlo Teteria, Petro Doroshenko | ||||||

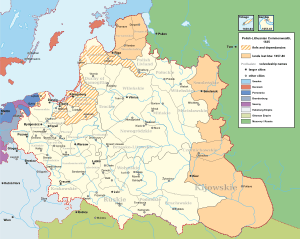

The Russo-Polish War of 1654–1667, also called Thirteen Years' War,[1] First Northern War,[1] or the War for Ukraine, was a major conflict between Tsardom of Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Between 1655 and 1660, the Second Northern War was also fought in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, thus this period became known in Poland as "The Deluge". The Commonwealth initially suffered defeats, but regained its ground and won most of the battles. However its plundered economy was not able to fund the long conflict. Facing internal crisis and civil war, Poland was forced to sign a truce. The war ended with significant Russian territorial gains and marked the beginning of the rise of Russia as a great power in Eastern Europe.

Background

The conflict was triggered by the Khmelnytsky Rebellion of Zaporozhian Cossacks against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Cossack leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, derived his main foreign support from Alexis of Russia and promised his allegiance in recompense. Although the Zemsky Sobor of 1651 was poised to accept the Cossacks into the Moscow sphere of influence and to enter the war against Poland-Lithuania on their side, the Tsar waited until 1653, when a new popular assembly eventually authorized the protectorate of Ukraine with Tsardom of Russia. After the Cossacks ratified this agreement at the Pereyaslav Council the Russo-Polish War became inevitable.

Invasion of the Commonwealth

In July 1654 the Russian army of 41,000 (nominally under the Tsar, but in fact commanded by Princes Yakov Cherkassky, Nikita Odoevsky and Ivan Khovansky) captured the border forts of Bely and Dorogobuzh and laid siege to Smolensk.

The Russian position at Smolensk was endangered as long as Great Lithuanian Hetman, Prince Janusz Radziwiłł, with a 10,000 man garrison, held Orsha, slightly to the west.[2] Cherkassky took Orsha; forces under his command, led by Kniaz (Prince, or Duke) Yuri Baryatinsky, forced Radziwill to retreat in the Battle of Shklov (also known as the Battle of Szkłów, Battle of Shkloŭ, or Battle of Shklow, which took place during a solar eclipse, and for which both sides claimed victory), fought near Shklov on August 12.[2] Radziwill was again defeated twelve days later at the Battle of Shepeleviche. After a three-month siege, Smolensk — the main object of the previous Russo–Polish War — fell to the Russians on 23 September.

In the meantime, Prince Aleksey Trubetskoy led the southern flank of the Russian army from Bryansk to Ukraine. The territory between the Dnieper and Berezina was overrun quickly, with Trubetskoy taking Mstislavl and Roslavl and his Ukrainian allies capturing Homel. On the northern flank, V.B. Sheremetev set out from Pskov and seized the Lithuanian cities of Nevel (July 1), Polotsk (July 17), and Vitebsk (November 17).

Thereupon the Tsar's troops swarmed over Polish Livonia and firmly established themselves in Ludza and Rezekne. Simultaneously, the combined forces of Khmelnitsky and the Russian Boyar Buturlin struck against Volynia. Despite many disagreements between the commanders, they took hold of Ostrog and Rovno by the end of the year.

Campaign of 1655

In the winter and spring of 1655, (Prince) Radziwill launched a counter-offensive in Belarus, recapturing Orsha and besieging Mogilyov. This siege continued for three months with no conclusion. In January, Sheremetev and Khmelnitsky were defeated at the Battle of Okhmativ, while a second Polish army (allied with the Tatars) crushed a Russian-Ukrainian contingent at Zhashkov.

Alarmed by these reverses, the Tsar hastened from Moscow and at his instigation a massive offensive was launched. The Lithuanian forces offered little effective resistance and surrendered Minsk to the Cossacks and Cherkassky on 3 July. Vilnius, the capital of the Great Duchy of Lithuania, was taken by the Russians on 31 July. This success was followed up by the conquest of Kaunas and Hrodno in August.

Elsewhere, Prince Volkonsky sailed from Kiev up the Dnieper and the Pripyat, routing the Lithuanians and capturing Pinsk on his way. Trubetskoy's unit overran Slonim and Kletsk, while Sheremetev managed little beyond seizing Velizh on June 17. A Lithuanian garrison still resisted the Cossacks' siege in Stary Bykhov, when Khmelnitsky and Buturlin were already active in Galicia. They attacked the Polish city of Lwów in September and entered Lublin after Pawel Jan Sapieha's defeat near Brest.

Armistice

The Russian advance into the Polish Commonwealth led to the kingdom of Sweden invading Poland in 1655 under King Charles X.

Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin then opened negotiations with the Poles and signed an armistice, Truce of Vilna, on 2 November. After that, Russian forces marched on Swedish Livonia and besieged Riga in the Russo-Swedish War of 1656-1658, a theater of the Second Northern War.

Khmelnytsky was not against this temporary truce and supported the Tsar though he warned him of Polish furtiveness.[3]

Campaign against Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky, the newly elected hetman in 1657 upon the death of Khmelnytsky, allied himself with the Poles in Sept. 1658, creating the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia. However, the Cossacks were also beset with the start of a civil war with this Commonwealth treaty and a new Treaty of Pereyaslav with Russia in 1659.

The Tsar concluded with Sweden the advantageous Treaty of Valiersar, which allowed him to resume hostilities against the Poles in October 1658, capturing Wincenty Gosiewski at the Battle of Werki. In the north, Sapieha's attempt to blockade Vilnius was checked by Prince Yury Dolgorukov on October 11. In the south, the Ukrainian Vyhovsky failed to wrest Kiev from Sheremetev's control where Russians kept their garrison. In July 1659, however, Vyhovsky and his Crimean Tatar allies inflicted a heavy defeat upon Trubetskoy's army, then besieging Konotop.

Change of luck

The threat to the Russians during their conquests in Ukraine was relieved after Vyhovsky lost his alliance with Crimean Khanate due to Kosh Otaman Ivan Sirko campaign who later attacked Chyhyryn as well. An uprising arose in the Siever Ukraine where Vyhovsky stationed few Polish garrisons. During the uprising perished a Ukrainian nobleman Yuri Nemyrych who was considered the original author of the Hadyach Treaty. Together with the Uman colonel Mykhailo Khanenko Sirko has led a full scale uprising throughout Ukraine. The mutinied Cossacks requested Vyhovsky to surrender the hetman's attributes and reelect Khmelnitsky's son Yurii once again as the true hetman of Ukraine. Both forces faced off near the village of Hermanivka. There the rest of cossacks deserted Vyhovsky and rallied under Yuri Khmelnytsky, while Vyhovsky was left with the Polish troops and other mercenaries. A council was gathered with participation of both sides where the union with Poland-Lithuania was proclaimed unpopular and due to the rising arguments and threats Vyhovsky has left the meeting. The council elected Khmelnytsky the new hetman and an official request to surrender the power was sent to Vyhovsky who had no other choice as to comply.

Russian forces stunned at Konotop tried to renegotiate a peace treaty on any terms. However, the change of powers within the Cossack Hetmanate reflected the amount influence of the Russian foreign policy in Ukraine and reassured voivode Trubetskoi. Trubetskoi invited Khmelnytsky to renegotiate. Advising by starshyna not to rush it Yuri Khmelnytsky sent out Petro Doroshenko with an official request. Trubetskoi, however, insisted on the presence of the hetman to sign the official treaty at Pereyaslav (see Pereyaslav Articles). Arriving there Khmelnytsky discovered that he was ambushed.

End of the war

The tide turned in Poland's favor in 1660. Polish King John II Casimir, having concluded the Second Northern War against Sweden with the Treaty of Oliva, was now able to concentrate all his forces on the Eastern front.[1]:186 Sapieha and Stefan Czarniecki defeated Khovansky at the Battle of Polonka on 27 June.[1]:186 Then, Potocki and Lubomirski attacked V.B. Sheremetev in the Battle of Cudnów and forced him to capitulate on 2 Nov., after persuading Yurii Khmelnytsky to withdraw on 17 Oct.[1]:186 These reverses forced the Tsar to accept the Treaty of Kardis, by way of averting a new war against Sweden.

Towards the end of 1663, the Polish King crossed the Dnieper and invaded Left-bank Ukraine. Most towns in his path would surrender without resistance, but his siege of Hlukhiv in January was a costly failure and he suffered a further setback at Novgorod-Seversky. The Commonwealth did defeat Khovansky's forces at Vitebsk in summer 1664.[1]:186

Peace negotiations dragged on from 1664 until January 1667, when civil war forced the Poles to conclude the Treaty of Andrusovo, whereby the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceded to Russia the fortress of Smolensk and Ukraine on the left bank of the Dnieper River (including Kiev), while the Commonwealth retained the right-bank Ukraine.[1]:186

In addition to the territorial changes from the war, this conflict sparked major changes in the Russian military. While the Russian army was still a "semi-standing, mobilized seasonally", this conflict moved it along the path toward a standing army, laying the groundwork for Russian military successes under Peter the Great and Catherine the Great.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558–1721. Longman. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- 1 2 (Polish) Kubala L. WOJNA MOSKIEWSKA. R. 1654–1655. SZKICE HISTORYCZNE, SER.III, WARSZAWA, 1910: Chapter VII, Bitwa pod Szkłowem i pod Szepielewiczami also available as John III Sobieski (King of Poland) (1845). Ojczyste spominki w pismach do dziejów dawnéj Polski: diaryusze, relacye, pamiȩtniki ... Tudzież listy historyczne do panowania królów Jana Kazimierza i Michała Korybuta, oraz listy Jana Sobieskiego. J. Cypcer. pp. 114–115. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ↑ Грамоты из переписки царя Алексея Михайловича с Богданом Хмельницким в 1656 г.

- ↑ Agoston, Gabor (Spring 2011). "Military Transformation in the Ottoman Empire and Russia, 1500-1800". Kritika. 12 (2): 284. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Malov, A. V. (2006). Russo-Polish War (1654–1667). Moscow: Exprint. ISBN 5940381111.

External links

-

Media related to Polish-Russian War 1654-1667 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Polish-Russian War 1654-1667 at Wikimedia Commons - Russo-Polish War, 1654–1667

- The Muscovite Wars and the Polish Ascendancy