Samuel Goldwyn

| Samuel Goldwyn | |

|---|---|

|

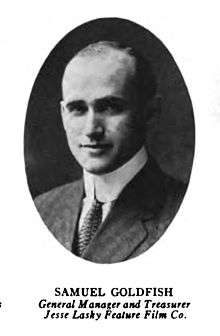

A picture of Goldwyn, prior to his name change in 1916. | |

| Born |

Szmuel Gelbfisz 17 August 1879 Warsaw, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died |

31 January 1974 (aged 94) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Other names | Samuel Goldfish, Mister Malaprop |

| Years active | 1917-53 |

| Spouse(s) |

Blanche Lasky (1910-1915; divorced; 1 child) Frances Howard (1925-1974; his death; 1 child) |

Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz (Yiddish: שמואל געלבפֿיש); August 17, 1879 – January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Jewish Polish American film producer. He was most well known for being the founding contributor and executive of several motion picture studios in Hollywood.[1] His awards include the 1973 Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award,[2] the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award in 1947, and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1958.

Early life

Goldwyn was born Szmuel Gelbfisz[3] in Warsaw, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire, to a Hasidic, Polish Jewish family. His parents were Aaron Dawid Gelbfisz (1852-1895), a peddler, and his wife, Hanna Reban (née Jarecka; 1855-1924).[4] At an early age, he left Warsaw on foot and penniless. He made his way to Birmingham, United Kingdom, where he remained with relatives for a few years using the name Samuel Goldfish. He was 16 when his father died.

In 1898, he emigrated to the United States, but fearing refusal of entry, he got off the boat in Nova Scotia, Canada, before moving on to New York in January 1899. He found work in upstate Gloversville, New York, in the bustling garment business. Soon his innate marketing skills made him a very successful salesman at the Elite Glove Company. After four years, as vice-president of sales, he moved back to New York City and settled at 10 West 61st Street.[5]

Paramount

In 1913, Goldwyn along with his brother-in-law Jesse L. Lasky, Cecil B. DeMille, and Arthur Friend formed a partnership, The Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, to produce feature-length motion pictures. Film rights for the stage play, The Squaw Man were purchased for $4,000 and Dustin Farnum was hired for the leading role. Shooting for the first feature film made in Hollywood began on December 29, 1913.[6]

In 1914, Paramount was a film exchange and exhibition corporation headed by W. W. Hodkinson. Looking for more movies to distribute, Paramount signed a contract with the Lasky Company on June 1, 1914 to supply 36 films per year. One of Paramount's other suppliers was Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Company. The two companies merged on June 28, 1916 forming The Famous Players-Lasky Corporation. Zukor had been quietly buying Paramount stock, and two weeks prior to the merger, became president of Paramount Pictures Corporation and had Hodkinson replaced with Hiram Abrams, a Zukor associate.[7]

With the merger, Zukor became president of both Paramount and Famous Players-Lasky, with Goldwyn being named chairman of the board of Famous Players-Lasky, and Jesse Lasky first vice-president. After a series of conflicts with Zukor, Goldwyn resigned as chairman of the board, and as member of the executive committee of the corporation on September 14, 1916. Goldwyn was out as an active member of management, although he still owned stock and was a member of the board of directors. Famous Players-Lasky would later become part of Paramount Pictures Corporation, and Paramount would become one of Hollywood's major studios.[8]

Goldwyn Pictures

In 1916, Goldwyn partnered with Broadway producers Edgar and Archibald Selwyn, using a combination of both names to call their movie-making enterprise Goldwyn Pictures. Seeing an opportunity, Samuel Gelbfisz then had his name legally changed to Samuel Goldwyn, which he used for the rest of his life. Goldwyn Pictures proved successful but it is their "Leo the Lion" trademark for which the organization is most famous.

On April 10, 1924, Goldwyn Pictures was acquired by Marcus Loew and merged into his Metro Pictures Corporation. Despite the inclusion of his name, Goldwyn had no role in the management or production at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Samuel Goldwyn Productions

Before the sale and merger of Goldwyn Pictures in April 1924, Goldwyn had established Samuel Goldwyn Productions in 1923 as a production-only operation (with no distribution arm). Their first feature was Potash and Perlmutter, released in September 1923 through First National Pictures. Some of the early productions bear the name "Howard Productions", named for Goldwyn's wife Frances Howard.

For 35 years, Goldwyn built a reputation in filmmaking and developed an eye for finding the talent for making films. William Wyler directed many of his most celebrated productions, and he hired writers such as Ben Hecht, Sidney Howard, Dorothy Parker, and Lillian Hellman. (According to legend, at a heated story conference Goldwyn scolded someone—in most accounts Mrs. Parker, who recalled he had once been a glove maker—with the retort: "Don't you point that finger at me. I knew it when it had a thimble on it!" Another time, when he demanded a script that ended on a happy note, she said: "I know this will come as a shock to you, Mr. Goldwyn, but in all history, which has held billions and billions of human beings, not a single one ever had a happy ending."[9])

During that time, Goldwyn made numerous films and reigned as the most successful independent producer in the US. Many of his films were forgettable; his collaboration with John Ford, however, resulted in Best Picture Oscar nomination for Arrowsmith (1931). William Wyler was responsible for most of Goldwyn's highly lauded films, with Best Picture Oscar nominations for Dodsworth (1936), Dead End (1937), Wuthering Heights (1939), The Little Foxes (1941) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). The leading actors in several of Goldwyn films, especially those directed by William Wyler, were also Oscar-nominated for their performances.

Throughout the 1930s, Goldwyn released all his films through United Artists, but beginning in 1941, and continuing almost through the end of his career, Goldwyn released his films through RKO Radio Pictures.

Oscar

In 1946, the year he was honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences with the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, Goldwyn's drama, The Best Years of Our Lives, starring Myrna Loy, Fredric March, Teresa Wright and Dana Andrews, won the Academy Award for Best Picture. In the 1950s Samuel Goldwyn turned to making a number of musicals including the 1952 hit Hans Christian Andersen (his last with Danny Kaye, with whom he had made many others), and the 1955 hit Guys and Dolls starring Marlon Brando, Jean Simmons, Frank Sinatra, and Vivian Blaine, which was based on the equally successful Broadway musical. This was the only independent film that Goldwyn ever released through MGM.

In his final film, made in 1959, Samuel Goldwyn brought together African-American actors Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Pearl Bailey in a film rendition of the George Gershwin opera, Porgy and Bess. Released by Columbia Pictures, the film was nominated for three Oscars, but won only one. It was also a critical and financial failure, and the Gershwin family reportedly disliked the film and eventually pulled it from distribution. The film turned the opera into an operetta with spoken dialogue in between the musical numbers. Its reception was a huge disappointment to Goldwyn, who, according to biographer Arthur Marx, saw it as his crowning glory and had wanted to film Porgy and Bess since he first saw it onstage in 1935.

Awards

- In 1957, Goldwyn was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for his outstanding contributions to humanitarian causes.

- On March 27, 1971, Goldwyn was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard Nixon.[10]

Death

Goldwyn died at his home in Los Angeles in 1974 from natural causes, at the probable age of 94. He is interred at Glendale's Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery near his wife, Frances Howard and director, George Cukor.[11][12][13] In the 1980s, Samuel Goldwyn Studio was sold to Warner Bros. There is a theater named after him in Beverly Hills and he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1631 Vine Street for his contributions to motion pictures on February 8, 1960.[14][15]

Marriages

From 1910 to 1915, Goldwyn was married to Blanche Lasky, a sister of Jesse L. Lasky. The marriage produced a daughter, Ruth. In 1925, he married actress Frances Howard to whom he remained married for the rest of his life. Their son, Samuel Goldwyn, Jr., would eventually join his father in the business.

Grandchildren

Samuel Goldwyn's grandchildren include

- Francis Goldwyn, founder of the Manhattan Toy Company and Managing Member of Quorum Associates LLC

- Tony Goldwyn, actor, producer and director. currently starring as President Fitzgerald Grant III in TV's Scandal

- John Goldwyn, film producer

- Peter Goldwyn, the current vice-president of Samuel Goldwyn films

- Catherine Goldwyn, created Sound Art, a non-profit organization that teaches popular music all over Los Angeles

- Liz Goldwyn, has a film on HBO called Pretty Things, featuring interviews with queens from the heyday of American burlesque;[16][17] her book, an extension of the documentary titled, Pretty Things: The Last Generation of American Burlesque Queens, was published in October 2006 by HarperCollins.[18]

- Rebecca Goldwyn (August 15, 1955-September 1, 1955) (interred at Forest Lawn in Glendale, CA)[19]

Nephew

Goldwyn's relatives include Fred Lebensold (see Lebensold Family), an award-winning architect (best known as the designer of multiple concert halls in Canada and the United States). Fred was the son of Sam's younger sister, Manya (who, despite the best efforts of Sam and his brother Ben in 1939 and 1940, could not be extricated from the Warsaw Ghetto and perished in the Holocaust).

The Samuel Goldwyn Foundation

Samuel Goldwyn's will created a multimillion-dollar charitable foundation in his name. Among other endeavors, the Samuel Goldwyn Foundation funds the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards, provided construction funds for the Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Regional Library, and provides ongoing funding for the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

The Samuel Goldwyn Company

Several years after the Sr. Goldwyn's death, his son, Samuel Goldwyn Jr., initiated an independent film and television distribution company dedicated to preserving the integrity of Goldwyn's ambitions and work. The company's assets were later acquired by Orion Pictures, and in 1997, passed on to Orion's current parent company, MGM. Several years later, the Samuel Goldwyn Jr. Family Trust and Warner Bros. acquired the rights to all the Goldwyn-produced films except The Hurricane, which was returned to MGM division United Artists.

Goldwynisms

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Samuel Goldwyn |

Samuel Goldwyn was also known for malapropisms, paradoxes, and other speech errors called 'Goldwynisms' ("A humorous statement or phrase resulting from the use of incongruous or contradictory words, situations, idioms, etc.") being frequently quoted. For example, he was reported to have said, "I don't think anybody should write his autobiography until after he's dead."[20] and "Include me out." Some famous Goldwyn quotations are misattributions. For example, the statement attributed to Goldwyn that "a verbal contract isn't worth the paper it's written on" is actually a well-documented misreporting of an actual quote praising the trustworthiness of a colleague: "His verbal contract is worth more than the paper it's written on". The identity of the colleague is variously reported as Joseph M. Schenk[21] or Joseph L. Mankiewicz[22] Goldwyn himself was reportedly aware of—and pleased by—the misattribution.

Upon being told that a book he had purchased for filming, The Well of Loneliness, couldn't be filmed because it was about lesbians, he reportedly replied: "That's all right, we'll make them Hungarians." The same story was told about the 1934 rights to The Children's Hour with the response "That's okay; we'll turn them into Armenians."[23] Upon being told that a dictionary had included the word "Goldwynism" as synonym for malapropism, he raged: "Goldwynisms! They should talk to Jesse Lasky!"

Having many writers in his employ, Goldwyn may not have come up with all of these on his own. In fact Charlie Chaplin took credit for penning the line, "In two words: im-possible"; and the quote, "the next time I send a damn fool for something, I go myself," has also been attributed to Michael Curtiz.

In the Grateful Dead's Scarlet Begonias,[24] the line "I ain't often right but I've never been wrong" appears in the bridge—this is very similar to Goldwyn's "I’m willing to admit that I may not always be right, but I am never wrong."

References

- ↑ Obituary Variety, February 6, 1974, p. 63.

- ↑ Jang, Meena (January 31, 2015). "Samuel Goldwyn: Remembering the Movie Mogul on the Anniversary of His Death". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ The sz-spelling is a not-uncommon Polish transliteration for the Yiddish sh-sound, which only requires a single letter in that language.

- ↑ "Goldwyn".

- ↑ A. Scott Berg, Goldwyn, a Biography

- ↑ A.Scott Berg, Goldwyn, a Biography. pp. 31–35, 41.

- ↑ A.Scott Berg, Goldwyn, a Biography. pp. 49, 58

- ↑ A.Scott Berg, Goldwyn, a Biography. pp. 58, 59, 63

- ↑ Silverstein, Stuart Y., ed. (1996, paperback 2001). Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker. New York: Scribner. p. 42, n. 75. ISBN 0-7432-1148-0. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Richard Nixon, 1971. 1971. p. 490. ISBN 0160588634. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ Samuel Goldwyn at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Frances Howard Goldwyn (1903 - 1976) - Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ "George Cukor (1899 - 1983) - Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ "Samuel Goldwyn | Hollywood Walk of Fame". www.walkoffame.com. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ "Samuel Goldwyn". latimes.com. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ Pretty Things at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Pretty Things". Liz Goldwyn Films. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ Pretty Things: The Last Generation of American Burlesque Queens. Google Books. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ "Rebecca Goldwyn (1955 - 1955) - Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ Quoted in Arthur Marx, Goldwyn: The Man Behind the Myth (1976), prologue.

- ↑ Paul F. Boller, John George, They Never Said It (1990), p. 42.

- ↑ Carol Easton, The Search for Sam Goldwyn (1976).

- ↑ These Three

- ↑ "The Annotated "Scarlet Begonias"". ucsc.edu.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samuel Goldwyn. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Samuel Goldwyn |

- Samuel Goldwyn at the Internet Movie Database

- American Masters: Sam Goldwyn

- The American Presidency Project