Samaritan Hebrew

| Samaritan Hebrew | |

|---|---|

| עברית ‘Ivrit | |

| Region | Israel and Palestinian territories, predominantly in Nablus and Holon |

| Extinct |

ca. 2nd century[1] survives in liturgical use |

| Samaritan abjad | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

smp |

| Glottolog |

sama1313[2] |

| Linguasphere |

12-AAB |

Samaritan Hebrew (Hebrew: עברית שומרונית) is a reading tradition as used liturgically by the Samaritans for reading the Ancient Hebrew language of the Samaritan Pentateuch, in contrast to Biblical Hebrew (the language of the Masoretic Jewish Pentateuch).

For the Samaritans, Ancient Hebrew as a spoken everyday language became extinct and was succeeded by Samaritan Aramaic, which itself ceased to be a spoken language some time between the 10th and the 12th centuries and succeeded by Arabic (or more specifically Samaritan Palestinian Arabic).

The phonology of Samaritan Hebrew is highly similar to that of Samaritan Arabic, used by the Samaritans in prayer.[3] Today, the spoken vernacular among Samaritans is evenly split between Modern Israeli Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic, depending on whether they reside in Holon or in Shechem (i.e. Nablus).

History and discovery

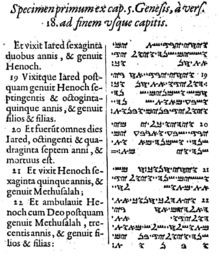

The Samaritan language first became known in detail to the Western world with the publication of a manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch in 1631 by Jean Morin.[5] In 1616 the traveler Pietro della Valle had purchased a copy of the text in Damascus, and this manuscript, now known as Codex B, was deposited in a Parisian library.[6] Between 1815 and 1835, Wilhelm Gesenius wrote his treatises on the original of the Samaritan version, proving that it postdated the Masoretic text.[7]

Between 1957 and 1977 Ze'ev Ben-Haim published in five volumes his monumental Hebrew work on the Hebrew and Aramaic traditions of the Samaritans. Ben-Haim, whose views prevail today, proved that modern Samaritan Hebrew is not very different from Second Temple Samaritan, which itself was a language shared with the other residents of the region before it was supplanted by Aramaic.[8]

Orthography

.jpg)

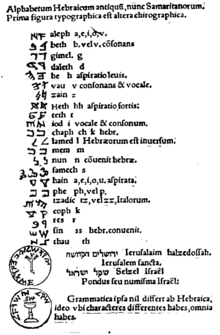

Samaritan Hebrew is written in the Samaritan alphabet, a direct descendant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, which in turn is a variant of the earlier Phoenician alphabet.

The Samaritan alphabet is close to the script that appears on many Ancient Hebrew coins and inscriptions.[9] By contrast, all other varieties of Hebrew, as written by Jews, employ the later 'square' Hebrew alphabet, which is in fact a variation of the Aramaic alphabet (more specifically, a form of the Assyrian script) that Jews began using in the Babylonian exile following the exile of the Kingdom of Judah in the 6th century BCE. During the 3rd century BCE, Jews began to use this stylized "square" form of the Aramaic alphabet that was used by the Persian Empire, which in turn was adopted from the Assyrians,[10] while the Samaritans continued to use the paleo-Hebrew script, which evolved into the Samaritan script.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar~Uvular | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emp. | plain | emp. | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Stop | voiceless | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sˤ | ʃ | ||||

| voiced | z | ʕ | |||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

Samaritan Hebrew shows the following consonantal differences from Biblical Hebrew: The original phonemes */b g d k p t/ do not have spirantized allophones, though at least some did originally in Samaritan Hebrew (evidenced in the preposition "in" ב- /af/ or /b/). */p/ has shifted to /f/ (except occasionally */pː/ > /bː/). */w/ has shifted to /b/ everywhere except in the conjunction ו- 'and' where it is pronounced as /w/. */ɬ/ has merged with /ʃ/, unlike in all other contemporary Hebrew traditions in which it is pronounced /s/. The laryngeals /ʔ ħ h ʕ/ have become /ʔ/ or null everywhere, except before /a ɒ/ where */ħ ʕ/ sometimes become /ʕ/. /q/ is sometimes pronounced as [ʔ], though not in Pentateuch reading, as a result of influence from Samaritan Arabic.[12] /q/ may also be pronounced as [χ], but this occurs only rarely and in fluent reading.[12]

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː | (o) |

| Open | a aː | ɒ ɒː |

| Reduced | (ə) | |

Phonemic length is contrastive, e.g. /rɒb/ רב 'great' vs. /rɒːb/ רחב 'wide'.[14] Long vowels are usually the result of the elision of guttural consonants.[14]

/i/ and /e/ are both realized as [ə] in closed post-tonic syllables, e.g. /bit/ בית 'house' /abbət/ הבית 'the house' /ger/ גר /aggər/ הגר.[15] In other cases, stressed /i/ shifts to /e/ when that syllable is no longer stressed, e.g. /dabbirti/ דברתי but דברתמה /dabbertimma/.[15] /u/ and /o/ only contrast in open post-tonic syllables, e.g. ידו /jedu/ 'his hand' ידיו /jedo/ 'his hands', where /o/ stems from a contracted diphthong.[16] In other environments, /o/ appears in closed syllables and /u/ in open syllables, e.g. דור /dor/ דורות /durot/.[16]

Stress

Stress generally differs from other traditions, being found usually on the penultimate and sometimes on the ultimate.

Grammar

Pronouns

Personal

| I | anáki |

| you (male) | átta |

| you (female) | átti (note the final yohdh) |

| he | û |

| she | î |

| we | anánu |

| you (male, plural) | attímma |

| you (female, plural) | éttên |

| they (male) | ímma |

| they (female) | ínna |

Demonstrative

This: masc. ze, fem. zéot, pl. ílla.

That: alaz (written with a he at the beginning).

Relative

Who, which: éšar.

Interrogative

Who? = mi. What? = ma.

Noun

When suffixes are added, ê and ô in the last syllable may become î and û: bôr (Judean bohr) "pit" > búrôt "pits". Note also af "anger" > éppa "her anger".

Segolates behave more or less as in other Hebrew varieties: beţen "stomach" > báţnek "your stomach", ke′seph "silver" > ke′sefánu (Judean Hebrew kaspe′nu) "our silver", dérek > dirkakimma "your (m. pl.) road" but áreş (in Judean Hebrew: ’e′rets) "earth" > árşak (Judean Hebrew ’arts-ekha) "your earth".

Article

The definite article is a- or e-, and causes gemination of the following consonant, unless it is a guttural; it is written with a he, but as usual, the h is silent. Thus, for example: énnar / ánnar = "the youth"; ellêm = "the meat"; a'émur = "the donkey".

Number

Regular plural suffixes are -êm (Judean Hebrew -im) masc., -ôt (Judean Hebrew: -oth.) fem: eyyamêm "the days", elamôt "dreams".

Dual is sometimes -ayem (Judean Hebrew: a′yim), šenatayem "two years", usually -êm like the plural yédêm "hands" (Judean Hebrew yadhayim.)

Tradition of Divine name

Samaritans have the tradition of either spelling out loud with the Samaritan letters

"Yohth, Ie', Baa, Ie’ "

or saying "Shema" meaning "(The Divine) Name" in Aramaic, similar to Judean Hebrew "Ha-Shem" .

Verbs

Affixes are:

| perfect | imperfect | |

| I | -ti | e- |

| you (male) | -ta | ti- |

| you (female) | -ti | ? |

| he | - | yi- |

| she | -a | ti- |

| we | ? | ne- |

| you (plural) | -tímma | te- -un |

| you (female, plural) | -tên | ? |

| they (male) | -u | yi- -u |

| they (female) | ? | ti- -inna |

Particles

Prepositions

"in, using", pronounced:

- b- before a vowel (or, therefore, a former guttural): b-érbi = "with a sword"; b-íštu "with his wife".

- ba- before a bilabial consonant: bá-bêt (Judean Hebrew: ba-ba′yith) "in a house", ba-mádbar "in a wilderness"

- ev- before other consonant: ev-lila "in a night", ev-dévar "with the thing".

- ba-/be- before the definite article ("the"): barrášet (Judean Hebrew: Bere’·shith′) "in the beginning"; béyyôm "in the day".

"as, like", pronounced:

- ka without the article: ka-demútu "in his likeness"

- ke with the article: ké-yyôm "like the day".

"to" pronounced:

- l- before a vowel: l-ávi "to my father", l-évad "to the slave"

- el-, al- before a consonant: al-béni "to the children (of)"

- le- before l: le-léket "to go"

- l- before the article: lammúad "at the appointed time"; la-şé'on "to the flock"

"and" pronounced:

- w- before consonants: wal-Šárra "and to Sarah"

- u- before vowels: u-yeššeg "and he caught up".

Other prepositions:

- al: towards

- elfáni: before

- bêd-u: for him

- elqérôt: against

- balêd-i: except me

Conjunctions

- u: or

- em: if, when

- avel: but

Adverbs

- la: not

- kâ: also

- afu: also

- ín-ak: you are not

- ífa (ípa): where?

- méti: when

- fâ: here

- šémma: there

- mittét: under

References

- ↑ Samaritan Hebrew at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Samaritan". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Frederic Madden, History of Jewish Coinage and of Money in the Old and New Testament, page ii

- ↑ Exercitationes ecclesiasticae in utrumque Samaritanorum Pentateuchum, 1631

- ↑ Flôrenṭîn 2005, p. 1: "When the Samaritan version of the Pentateuch was revealed to the Western world early in the 17th century... [footnote: 'In 1632 the Frenchman Jean Morin published the Samaritan Pentateuch in the Parisian Biblia Polyglotta based on a manuscript that the traveler Pietro Della Valle had bought from Damascus sixteen years previously.]"

- ↑ Flôrenṭîn 2005, p. 2: "At the beginning of the 19th century, Wilhelm Gesenius wrote his great treatise on the origin of the Samaritan version. He compared it with the Masoretic text, analyzed the differences between the two versions, and proved that the Samaritan version postdates the Masoretic version of the Jews."

- ↑ Flôrenṭîn 2005, p. 4: "A completely new approach which prevails today was presented by Ben-Hayyim, whose scientific activity was focused on the languages of the Samaritans - Hebrew and Aramaic. Years before the publication ol his grammar, with its exhaustive description of SH, he indicated several linguistic phenomena common to SH on the one hand, and Mishnaic Hebrew (MH) and the Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls (HDSS), on the other. He proved that the language heard today when the Torah is road by the Samaritans in their synagogue is not very different from the Hebrew which once lived and flourished among the Samaritans before, during and after the time of the destruction of the Second Temple. The isoglosses common to SH. MH and HDSS led him to establish that the Hebrew heard in the synagogue by modernday Samaritans is not exclusively theirs, but rather this Hebrew or something resembling it, was also the language of other residents of Eretz Israel before it was supplanted by Aramaic as a spoken language."

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Samaritan Language and Literature". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Samaritan Language and Literature". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1993. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- ↑ Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, pp. 31,37.

- 1 2 Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, p. 34–35

- ↑ Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, pp. 43–44, 48.

- 1 2 Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, p. 47–48 (while Ben-Hayyim notates four degrees of vowel length, he concedes that only his "fourth degree" has phonemic value)

- 1 2 Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, p. 49

- 1 2 Ben-Ḥayyim 2000, p. 44, 48–49

Bibliography

- J. Rosenberg, Lehrbuch der samaritanischen Sprache und Literatur, A. Hartleben's Verlag: Wien, Pest, Leipzig.

- Ben-Ḥayyim, Ze'ev (2000). A Grammar of Samaritan Hebrew. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press. ISBN 1-57506-047-7.

- Flôrenṭîn, Moše (2005). Late Samaritan Hebrew: A Linguistic Analysis Of Its Different Types. BRILL. ISBN 9789004138414.

External links

-

"Samaritan Language and Literature". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"Samaritan Language and Literature". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921. -

"Samaritan Language and Literature". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

"Samaritan Language and Literature". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.