Sawfly

| Sawfly Temporal range: Triassic–Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

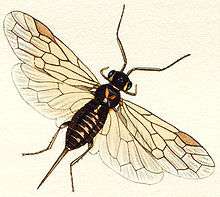

| Tenthredo mesomela | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Suborder: | Symphyta Gerstäcker 1867[1] |

| Superfamilies[2] | |

Sawflies are insects belonging to suborder Symphyta of the order Hymenoptera. Sawflies are distinguishable from most other hymenopterans by the broad connection between the abdomen and the thorax instead of a wasp waist, and by their caterpillar-like larvae.

Sawflies first appeared 250 million years ago in the Triassic, and the oldest family, the Xyeloidea, has existed from that time to this. Phylogenetically the sawflies consist of several basal groups within the Hymenoptera, so they do not form a separate clade of their own.

The common name comes from the saw-like appearance of the ovipositor, which the females use to cut into the plants where they lay their eggs. The great majority of species and families are plant-eating, though the youngest family, the Orussoidea, which is sister to the Apocrita (wasps, ants, and bees), is parasitic.

Large populations of species such as the pine sawfly can cause substantial damage to economic forestry, while others such as the iris sawfly are important pests in horticulture.

Etymology

The suborder name Symphyta derives from the Greek word symphyton, meaning "grown together", referring to the group's distinctive lack of a wasp waist between prostomium and peristomium.[3] Its common name, "sawfly", derives from the saw-like ovipositor that is used for egg-laying, in which a female makes a slit in either a stem or plant leaf to deposit the eggs.[4] The first known use of this name was in 1773.[5] Sawflies are also known as wood-wasps.[6]

Description

Adults

Adult sawflies, except for those in the family Cephidae, have structures that latch onto the underside of the fore wings to help hold the wings in place when the insect is at rest. These "cenchri", which are absent in the suborder Apocrita, are located behind the scutellum on the thorax. Adults of some species are carnivorous, eating other insects, but many also feed on nectar. Adults also have stronger antennae. Among the largest sawflies ever discovered was Hoplitolyda duolunica from the Mesozoic, with a body length of 55 millimetres (2.2 in) and a wingspan of 92 millimetres (3.6 in).[7]

Larvae

.ogv.jpg)

Some larvae look like caterpillars (the larvae of moths and butterflies), with some notable differences; (1) they have six or more pairs of prolegs (sometimes greatly reduced and difficult to see) on the abdomen, while caterpillars have five pairs or fewer, (2) they have two stemmata instead of a caterpillar's six, (3) caterpillars (except for a tiny minority) always have the two first abdominal segments legless, and (4) sawfly larvae have an invariably smooth head capsule with no cleavage lines, while lepidopterous caterpillars bear an inverted "Y" or "V" (adfrontal suture). Typical sawfly larvae are herbivorous, the group feeding on a wide range of plants. Individual species, however, are often quite specific in their choice of plants used for food. The larvae of various species exhibit leaf-mining, leaf "rolling", or gall formation. Three families are strictly xylophagous, and called "wood wasps", and one family is parasitic. The larvae that do not feed externally on plants are grub-like, without prolegs. When harassed, many sawfly larvae are able to squirt a foul liquid from their last segment.

Phylogeny

In his original description of Hymenoptera in 1863, Carl Gerstäcker divided them into three groups, Hymenoptera aculeata, Hymenoptera apocrita and Hymenoptera phytophaga.[8] But four years later in 1867, he described just two groups, H. apocrita syn. genuina and H. symphyta syn. phytophaga.[1] Consequently the name Symphyta is given to Gerstäcker as the zoological authority. In his description Gerstäcker distinguished the two groups by the transfer of the first abdominal segment to the thorax in the Apocrita, compared to the Symphyta. Consequently there are only eight dorsal half segments in the Apocrita, against nine in the Symphyta. The larvae are distinguished in a similar way.[9]

The Symphyta have therefore traditionally been considered, alongside the Apocrita, to form one of two suborders of Hymenoptera.[10][11] Symphyta are the more primitive group,[12] with comparatively complete venation, larvae that are largely phytophagous, and without a "wasp-waist", a symplesiomorphic feature. Together, the Symphyta make up less than 10% of hymenopteran species.[12] While the terms sawfly and Symphyta have been used synonymously, the Symphyta have also been divided into three groups, true sawflies (phyllophaga), woodwasps or xylophaga (Siricidae), and Orussidae. The three groupings have been distinguished by the true sawflies' ventral serrated or saw-like ovipositor for sawing holes in vegetation to deposit eggs, while the woodwasp ovipositor penetrates wood and the Orussidae behave as external parasitoids of wood-boring beetles. The woodwasps themselves are a paraphyletic ancestral grade. Despite these limitations, the terms have utility and are common in the literature.[11]

While most hymenopteran superfamilies are monophyletic, as is Hymenoptera, the Symphyta has long been seen to be paraphyletic.[13][14] Cladistic methods[15] and molecular phylogenetics are improving the understanding of relationships between the superfamilies, resulting in revisions at the level of superfamily and family. The Symphyta are the most primitive (basal) taxa within the Hymenoptera[14][12] (some going back 250 million years), and one of the taxa within the Symphyta gave rise to the monophyletic suborder Apocrita (wasps, bees, and ants). In cladistic analyses the Orussoidea are consistently the sister group to the Apocrita.[11][12]

The oldest unambiguous sawfly fossils date back to the Middle or Late Triassic. These fossils, from the family Xyelidae, are the oldest of all Hymenoptera.[16] One fossil, Archexyela ipswichensis from Queensland is between 205.6 to 221.5 million years of age, making it among the oldest of all sawfly fossils.[17] More Xyelid fossils have been discovered from the Middle Jurassic and the Cretaceous, but the family was less diverse then than during the Mesozoic and Tertiary. The subfamily Xyelinae were plentiful during these time periods, in which Tertiary faunas were dominated by the tribe Xyelini; these statements indicate a humid and warm climate.[18][19][20]

The cladogram is based on Schulmeister 2003.[21][22]

| Symphyta within Hymenoptera | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symphyta (red bar) are paraphyletic as Apocrita are excluded. |

Taxonomy

There are approximately 8,000 species of sawfly in more than 800 genera,[23] although new species continue to be discovered.[24][25] Early phylogenies, based on morphology and behaviour, such as that of Alexandr Rasnitsyn[26] identified nine clades though these did not reflect historical division into superfamilies and families. Such classifications were replaced by those using molecular methods, following the work of Dowton and Austin (1994).[27] As of 2013 these are treated as nine superfamilies (one extinct) and 25 families. Most sawflies belong to the Tenthredinoidea superfamily, with about 7,000 species worldwide. Tenthredinoidea has six families, of which Tenthredinidae is by far the largest with some 5,500 species.[10][2]

|

|

-

Anaxyeloidea

(Syntexis libocedrii) -

Orussoidea

(Orussus coronatus) -

Pamphilioidea

(Pamphilius sp.) -

Siricoidea

(Sirex noctilio) -

Tenthredinoidea

(Tenthredo notha) -

Xiphydrioidea

(Xiphydria camelus) -

Xyeloidea

(Xyela julii)

Distribution

Sawflies are widely distributed throughout the world, but their range continues to expand.[28]

Ecology

.jpg)

Sawflies are herbivores, feeding on plants that have a high concentration of chemical defences. These insects are either resistant to the chemical substances, or they avoid areas of the plant that have high concentrations of chemicals.[29] The larvae primarily feed in groups; they are folivores, eating plants and fruits on native trees and shrubs, though some are parasitic.[30][4][31] However, this is not always the case; Monterey pine sawfly (Itycorsia) larvae are solitary web-spinners that feed on Monterey pine trees inside a silken web.[32] The adults feed on pollen and nectar.[30]

Sawflies are eaten by a wide variety of predators. While many birds find the larvae distasteful, some such as the currawong and stonechats (Saxicola) eat both adults and larvae.[33][34] The larvae are an important food source for the chicks of several birds, including partridges.[35] Sawfly and moth larvae formed one third of the diet of nestling corn buntings (Emberiza calandra), with sawfly larvae being eaten more frequently on cool days.[36] Black grouse (Tetrao tetrix) chicks show a strong preference for sawfly larvae.[37][38] Sawfly larvae formed 43% of the diet of chestnut-backed chickadees (Poecile rufescens).[32] Small carnivorous mammals such as the masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), the northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) predate heavily on sawfly cocoons.[39] Insects such as ants and certain species of predatory wasps (Vespula vulgaris) eat adult sawflies and the larvae, as well as lizards and frogs.[40][41] Pardalotes, honeyeaters and fantails occasionally consume laid eggs, and several species of beetle larvae prey on the pupae.[34]

The larvae have several anti-predator adaptations. While adults are unable to sting, the larvae regurgitate a liquid from their mouths which is distasteful and irritating to potential predators, which makes them avoid the larvae.[4] The larvae also cluster together which reduces their chances of getting killed, and in some cases, a group of larvae will form together with their heads pointing outwards or tap their abdomens up and down.[34] Depending on how much is regurgitated, an insect (such as an ant) will either walk away and clean itself or become fatally affected by it.[42]

Parasites

Sawflies are hosts to many parasitoids, most of which are parasitic Hymenoptera; more than 40 species known to attack them. However, fewer than 10 of these species actually cause a significant impact on sawfly populations.[43]

Relationship with humans

Sawflies are important economic pests of forestry, where species in the Diprionidae such as the pine sawflies, Diprion pini and Neodiprion sertifer cause serious damage in regions such as Scandinavia. D. pini larvae defoliated 500,000 hectares (1,200,000 acres) in the largest outbreak in Finland, between 1998 and 2001. Up to 75% of the trees may die after such outbreaks, as D. pini can remove all the leaves late in the growing season, leaving the trees too weak to survive the winter.[44] Little damage to trees only occurs when the tree is large or when there is minimal presence of larvae. Eucalyptus trees can regenerate quickly from damage inflicted by the larvae; however, they can be substantially damaged from outbreaks, especially if they are young. The trees can be defoliated completely and may cause "dieback", stunting or even death.[34]

Sawflies are serious pests in horticulture. Different species prefer different host plants, often being specific to a family or genus of hosts. For example, Iris sawfly larvae, emerging in summer, can quickly defoliate species of Iris including the yellow flag and other freshwater species.[45] Similarly the rose sawflies Arge pagana and A. ochropus defoliate rose bushes.[46]

The giant woodwasp or horntail, Urocerus gigas, has a long ovipositor, which with its black and yellow coloration make it a good mimic of a hornet. Despite the alarming appearance, the insect cannot sting.[47] The eggs are laid in the wood of conifers such as Douglas fir, pine, spruce, and larch. The larvae eat tunnels in the wood, causing economic damage.[48]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Gerstaecker 1867.

- 1 2 Aguiar et al 2013.

- ↑ "Symphyta". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Australian Museum (20 October 2009). "Animal Species:Sawflies". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "Sawfly". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Gordh, G.; Headrick, D.H. (2009). A Dictionary of Entomology (2nd ed.). Wallingford: CABI. p. 1344. ISBN 978-1-84593-542-9.

- ↑ Gao, T.; Shih, C.; Rasnitsyn, A.P.; Ren, D.; Laudet, V. (2013). "Hoplitolyda duolunica gen. et sp. nov. (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Praesiricidae), the Hitherto largest sawfly from the Mesozoic of China". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e62420. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862420G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062420. PMC 3643952

. PMID 23671596.

. PMID 23671596. - ↑ Carus, J.V.; Gerstäcker, C.E.A. (1863). Handbuch der zoologie: bd. Arthropoden, bearb. von A. Gerstäcker. Raderthiere, würmer, echinodermen, coelenteraten und protozoen, bearb. von J. Victor Carus. 1863 (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Engelmann. p. 189. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1399. OCLC 2962429.

- ↑ Dallas, W.S. (1867). Insecta In: Günther, A.C.L.G The Zoological Record: Insecta, Volumes 3-4. London, UK: John van Voorst. p. 307. OCLC 6344527.

- 1 2 Goulet & Huber 1993.

- 1 2 3 Sharkey 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Mao et al 2015.

- ↑ Sharkey et al 2016.

- 1 2 Song et al 2016.

- ↑ Hennig 1969.

- ↑ Hermann, Henry R. (1979). Social Insects. 1. Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-323-14979-2.

- ↑ Engel, M.S. (2005). "A new sawfly from the Triassic of Queensland (Hymenoptera: Xyelidae)". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 51 (2): 558.

- ↑ Wang, M.; Rasinitsyn, A.P.; Ren, Dong (2014). "Two new fossil sawflies (Hymenoptera, Xyelidae, Xyelinae) from the Middle Jurassic of China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 88 (4): 1027–1033. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12269.

- ↑ Wang, M.; Gao, T.; Shih, C.; Rasinitsyn, A.P.; Ren, D. (2016). "The diversity and phylogeny of Mesozoic Symphyta (Hymenoptera) from Northeastern China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 90 (1): 376–377. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12662.

- ↑ Rasnitsyn, A.P. (2006). "Ontology of evolution and methodology of taxonomy". Paleontological Journal. 40 (S6): S679–S737. doi:10.1134/S003103010612001X.

- ↑ Schulmeister, S. (2003). "Simultaneous analysis of basal Hymenoptera (Insecta), introducing robust-choice sensitivity analysis". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 79: 245–275. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00233.x.

- ↑ Schulmeister, Susanne. "'Symphyta'". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Asaro 2008.

- ↑ Taeger, A.; Blank, S.M.; Liston, A. (2010). "World catalog of symphyta (Hymenoptera)". Zootaxa (2580): 1–1064. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ↑ Skvarla et al 2016.

- ↑ Rasnitsyn 1988.

- ↑ Dowton & Austin 1994.

- ↑ Looney et al 2016.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Gerald A.; Berenbaum, May R. (1991). Herbivores Their Interactions with Secondary Plant Metabolites (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-323-13940-3.

- 1 2 "Sawflies (Tenthredinoidae)". BBC. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Bandeili, Babak; Müller, Caroline (2009). "Folivory versus florivory—adaptiveness of flower feeding". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 79–88. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...79B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0615-9. PMID 19826770.

- 1 2 Kleintjes, P. K.; Dahlsten, D. L. (1994). "Foraging Behavior and Nestling Diet of Chestnut-Backed Chickadees in Monterey Pine" (PDF). The Condor. 96 (3): 647–653. doi:10.2307/1369468. JSTOR 1369468.

- ↑ Cummins, S.; O'Halloran, J. (2002). "An assessment of the diet of nestling Stonechats using compositional analysis: Coleoptera (beetles), Hymenoptera (sawflies, ichneumon flies, bees, wasps and ants), terrestrial larvae (moth, sawfly and beetle) and Arachnida (spiders and harvestmen) accounted for 81% of Stonechat nestling diet". Bird Study. 49 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1080/00063650209461258.

- 1 2 3 4 Phillips, Charlma (December 1992). "Spitfires – Defoliating Sawflies" (PDF). Department of Primary Industries and Resources. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Campbell, L.H.; Avery, M.I.; Donald, P.; Evans, A.D.; Green, R.E.; Wilson, J.D. (1997). A Review of the Indirect Effects of Pesticides on Birds (PDF) (Report). Peterborough, UK: Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Report. no 227. p. 27. ISSN 0963-8091.

- ↑ Brickle, N. W.; Harper, D. G. C. (1999). "Diet of nestling Corn Buntings Miliaria calandra in southern England examined by compositional analysis of faeces". Bird Study. 46 (3): 319–329. doi:10.1080/00063659909461145.

- ↑ Starling-Westerberg, A. (2001). "The habitat use and diet of Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in the Pennine hills of northern England". Bird Study. 48 (1): 76–89. doi:10.1080/00063650109461205.

- ↑ Cayford, J.T. (1990). "Distribution and habitat preferences of Black Grouse in commercial forests in Wales: conservation and management implications". Proceedings of the International Union Game of Biologists Congress. 19: 435–447.

- ↑ Holling, C. S. (1959). "The Components of Predation as Revealed by a Study of Small-Mammal Predation of the European Pine Sawfly" (PDF). The Canadian Entomologist. 91 (5): 293–320. doi:10.4039/Ent91293-5.

- ↑ Müller, Caroline; Brakefield, Paul M. (2003). "Analysis of a Chemical Defense in Sawfly Larvae: Easy Bleeding Targets Predatory Wasps in Late Summer". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 29 (12): 2683–2694. doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000008012.73092.01. ISSN 1573-1561. PMID 14969355.

- ↑ Petre, Charles-Albert; Detrain, Claire; Boevé, Jean-Luc (2007). "Anti-predator defence mechanisms in sawfly larvae of Arge (Hymenoptera, Argidae)". Journal of Insect Physiology. 53 (7): 668–675. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.04.007. PMID 17540402.

- ↑ Hairston, N.G. (1989). Ecological Experiments: Purpose, Design and Execution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-521-34692-4.

- ↑ Capinera 2008, p. 1827.

- ↑ Krokene, Paal (6 December 2014). "The common pine sawfly – a troublesome relative". Science Nordic. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Iris sawfly". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Large rose sawfly". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Great Wood Wasps". UK Safari. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Giant Woodwasp". Massachussetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

Bibliography

Books and chapters

- Asaro, Christopher. Sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). pp. 3250–3252., in Capinera (2008)

- Benson, R.B. (5 September 1952). Handbooks for the identification of British insects: VI Hymenoptera 2 Symphyta Section (b) (PDF). Royal Entomological Society of London.

- Blank, S.M.; Schmidt, S.; Taeger, A., eds. (2006). Recent sawfly research synthesis and prospects. Keltern: Goecke und Evers. ISBN 3-937783-19-9.

- Capinera, John L., ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology (2nd ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Goulet, Henri; Huber, John T., eds. (1993). Hymenoptera of the world: An identification guide to familes (PDF). Ottawa: Agriculture Canada. ISBN 0-660-14933-8.

- Hennig, Willi (1969). Die Stammesgeschichte der Insekten. Frankfurt: Waldemar Kramer.

- Liston, Andrew D; Taeger, Andreas; Blank, Stephan M. Comments on European Sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta. pp. 245–263., in Blank, Schmidt & Taeger (2006)

- Smith, DR. Systematics, life history, and distribution of sawflies. pp. 3–32., in Wagner & Raffa (1993)

- Smith, David R (September 1969). Nearctic sawflies I. Blennocampinae: Adults and larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1397). Washington: US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Smith, David R (September 1969). Nearctic sawflies II.Selandriinae: Adults and larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1398). Washington: US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Smith, David R (January 1971). Nearctic sawflies III. Heterarthrinae: Adults and larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1420). Washington: US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Smith, David R (June 1979). Nearctic sawflies IV. Allantinae: Adults and larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1595). Washington: US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Taeger, Andreas; Blank, Stephan M; Liston, Andrew D. European Sawflies (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) - A Species Checklist for the Countries (PDF). pp. 399–504., in Blank, Schmidt & Taeger (2006)

- Wagner, Michael R.; Raffa, Kenneth F., eds. (1993). Sawfly life history adaptations to woody plants. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 9780127300306.

Articles

- Aguiar, Alexandre P.; Deans, Andrew R.; Engel, Michael S.; Forshage, Mattias; Huber, John T.; Jennings, John T.; Johnson, Norman F.; Lelej, Arkady S.; Longino, John T.; Lohrmann, Volker; Mikó, István; Ohl, Michael; Rasmussen, Claus; Taeger, Andreas; Yu, Dicky Sick Ki (30 August 2013). "Order Hymenoptera". Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 51–62. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.12., in Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)

- Benson, Robert B (1962). "Holarctic sawflies (Hymenoptera : Symphyta)". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 12 (8): 379–409. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Dowton, M.; Austin, A. D. (11 October 1994). "Molecular phylogeny of the insect order Hymenoptera: apocritan relationships.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 91 (21): 9911–9915. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9911. PMC 44927

.

. - Gerstäcker, A (July 1867). "Ueber die Gattung Oxybelus Latr. und die bei Berlin vorkommenden Arten derselben". Zeitschrift für die gesammten Naturwissenschaft. 30 (VII): 1–144.

- Liston, Andrew; Knight, Guy; Sheppard, David; Broad, Gavin; Livermore, Laurence (29 August 2014). "Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Sawflies, 'Symphyta'". Biodiversity Data Journal. 2: e1168. doi:10.3897/BDJ.2.e1168.

- Looney, Chris; Smith, David R; Collman, Sharon J.; Langor, David W.; Peterson, Merrill A. (28 Apr 2016). "Sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) newly recorded from Washington State". Journal of Hymenoptera Research. 49: 129–159. doi:10.3897/JHR.49.7104.

- Mao, Meng; Gibson, Tracey; Dowton, Mark (March 2015). "Higher-level phylogeny of the Hymenoptera inferred from mitochondrial genomes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 84: 34–43. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.12.009.

- Rasnitsyn, A.P. (1988). "An outline of evolution of hymenopterous insects (order Vespida)". Oriental Insects. 22: 115–145.

- Sharkey, Michael J (2007). "Phylogeny and Classification of Hymenoptera" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1668: 521–548.

- Sharkey, Michael J.; Carpenter, James M.; Vilhelmsen, Lars; Heraty, John; Liljeblad, Johan; Dowling, Ashley P.G.; Schulmeister, Susanne; Murray, Debra; Deans, Andrew R.; Ronquist, Fredrik; Krogmann, Lars; Wheeler, Ward C. (February 2012). "Phylogenetic relationships among superfamilies of Hymenoptera". Cladistics. 28 (1): 80–112. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00366.x.

- Song, Sheng-Nan; Tang, Pu; Wei, Shu-Jun; Chen, Xue-Xin (16 February 2016). "Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial genomes in basal hymenopterans". Scientific Reports. 6: 20972. doi:10.1038/srep20972.

- Skvarla, Michael; Smith, David; Fisher, Danielle; Dowling, Ashley (9 May 2016). "Terrestrial arthropods of Steel Creek, Buffalo National River, Arkansas. II. Sawflies (Insecta: Hymenoptera: " Symphyta ")". Biodiversity Data Journal. 4: e8830. doi:10.3897/BDJ.4.e8830.

Catalogue of Symphyta

- Taeger, Andreas; Blank, Stephan M (12 September 1996). "Kommentare zur Taxonomie der Symphyta (Hymenoptera): Vorarbeiten zu einem Katalog der Pflanzenwespen, Teil 1". Beiträge zur Entomologie. Berlin. 46 (2): 251–275.

- Blank, Stephan (January 1996). "Revision of the sawflies described by Lothar Zirngiebl. (Preliminary studies for a catalogue of Symphyta, part 2.) (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Symphyta).". Spixiana. 19 (2): 195–219.

- Blank, Stephan M.; Shinohara, Akihiko; Taeger, Andreas (22 April 2008). "Revisionary Notes on Pamphiliid Sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta: Pamphiliidae) Preliminary studies for a catalogue of Symphyta, part 3.". Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift. 45 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1002/mmnd.19980450104.

- Blank, S.M.; Taeger, A. (1998). Comments on the taxonomy of Symphyta (Hymenoptera): (Preliminary studies for a catalogue of Symphyta, part 4) (PDF). pp. 141–174., in Taeger, A. & Blank, S. M. (eds.), Pflanzenwespen Deutschlands (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) Kommentierte Bestandsaufname. Deutsches Entomologisches Institut, Goecke& Evers, Keltern.

- Blank, S.M.; Groll, E.K.; Liston, A.D.; Prous, M.; Taeger, A. (2012). "ECatSym - Electronic World Catalog of Symphyta (Insecta, Hymenoptera). Program version 4.0 beta, data version 39". Müncheberg: Digital Entomological Information.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Symphyta |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Symphyta. |

- Alder-feeding Sawflies of Alaska United States Forest Service

- A sawfly injurious to young pines hosted by the UNT Government Documents Department

- Symphyta: Encyclopedia Brittanica 2016

- Chrysis.net: Taxonomy of Hymenoptera