Shia Islam in Lebanon

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,160,000[1] - 1,600,000[2][3] | |

| Languages | |

|

Vernacular: Lebanese Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Shia Islam) |

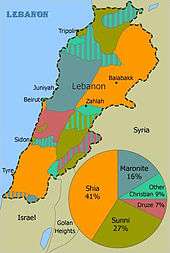

Shia Islam in Lebanon has a history of more than a millennium. According to CIA study, Lebanese Shia Muslims constitute 27% of Lebanon's population of approximately 4.3 million, which means they amount to 1,160,000.[1] According to other sources the Lebanese Shia Muslims constitute approximately 40% of the entire population (or 1.6 million out of a total population of 4 million).[2][4]

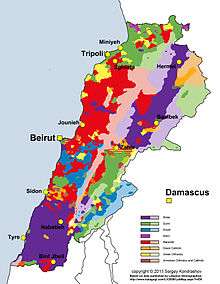

Most of its adherents live in the northern and western area of the Beqaa Valley, Southern Lebanon and Beirut's southern suburbs. The great majority of Shia Muslims in Lebanon are Twelvers, with an Alawite minority numbering in the tens of thousands in north Lebanon. Few Ismailis remain in Lebanon today, though the quasi-Muslim Druze sect, which split from Ismailism around a millennium ago, has hundreds of thousands of adherents.

Under the terms of an unwritten agreement known as the National Pact between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, Shias are the only sect eligible for the post of Speaker of Parliament.[5][6][7][8]

History

Origins

The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of both indigenous Phoenician elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview the lead investigator, Pierre Zalloua, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions: "Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[9]

Haplogroup J2 is also a significant marker in throughout Lebanon (29%). This marker found in many inhabitants of Lebanon, regardless of religion, signals pre-Arab descendants, including the Phoenicians. These genetic studies show us there is no significant differences between the Muslims and non-Muslims of Lebanon.[10] Genealogical DNA testing has shown that 24.8% of Lebanese Muslims (non-Druze) belong to the Y-DNA haplogroup J1. Although there is common ancestral roots, these studies show a very small difference was found between Muslims and non-Muslims in Lebanon, of whom only 17.1% have this haplotype. As haplogroup J1 finds its putative origins in the Arabian peninsula, this likely means that the lineage was introduced by Arabs beginning at the time of the 7th century Muslim conquest of the Levant and has persisted among the Muslim population ever since. On the other hand, only 4.7% of all Lebanese Muslims belong to haplogroup R1b, compared to 9.6% of Lebanese Christians. Modern Muslims in Lebanon thus do not seem to have a significant genetic influence from the Crusaders, who probably introduced this common Western Europen marker to the extant Christian populations of the Levant when they were active in the region from 1096 until around the turn of the 14th century.

A Shia emirate was established in Keserwan a mountain region overlooking the coastal area north of Beirut, in which they prospered for the next five centuries. The growth of Shia Islam in Lebanon stopped around the late thirteenth century, and subsequently Shia communities decreased in size. Keserwan began to lose its Shia character under the Assaf Sunni Turkomans whom the Mamluks appointed as overlords of the area in 1306. The process intensified around 1545 when the Maronites started migrating to Keserwan and Jbeil, encouraged by the Assafs, who sought to use them as a counterweight to the Shia Himada sheikhs who reemerged in Kesrewan in the 16th century. When in 1605 the Druze emir Fakhr al-Din Ma'n II took over Kesrewan, he entrusted its management to the Khazin Maronite family. The Khazins gradually colonized Kesrewan, purchasing Shia lands and founding churches and monasteries. They emerged as the predominant authority in the region at the expense of the Shia Hamedeh clan. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Khazins owned Kesrewan and only a few Shia villages survived. During the time of the Ottoman Empire the Shias suffered religious persecution and were often forced to flee their homes in search of refuge in the South. One example is the Lebanese city of Tripoli, which had formerly had a Shia Muslim majority. Many Lebanese Shia are rumored to have concealed their religious sect and acted as Sunni Muslims in fear of persecution. It is also rumored that some of the Shia permanently adopted the Sunni Muslim sect. The Ottomans and Druze were well allied and a Druze family seized power of Tripoli. Maronites who were persecuted by the Ottoman's and the Druze, sought refuge amongst the newly relocated Shia population in the South. Jezzine, once famously known as a Shia capital in Lebanon, is now known as a major Christian city in the South. The Shias withdrew further south and eventually had to abandon even Jezzine, which until the mid-eighteenth century had functioned as a center of Shia learning in Lebanon.[11]

Under Mamluk and Ottoman rule

The growth of Shia Islam in Lebanon stopped around the late thirteenth century, and subsequently Shia communities decreased in size. This development may be traced to 1291, when the Sunni Mamluks sent numerous military expeditions to subdue the Shias of Keserwan, a mountain region overlooking the coastal area north of Beirut. The first two Mamluk expeditions were defeated by the Shia in Keserwan. The third expedition, on the other hand, was overwhelmingly large and was able to defeat the Shia in Keserwan; many were brutally slaughtered, some fled through the mountains to northern Beqaa while others fled moving through the Beqaa plain, to a new safe haven in Jezzine. Keserwan began to lose its Shia character under the Assaf Sunni Turkomans whom the Mamluks appointed as overlords of the area in 1306. The process intensified around 1545 when the Maronites started migrating to Keserwan and Jbeil, encouraged by the Assafs, who sought to use them as a counterweight to the Shia Himada sheikhs who reemerged in Kesrewan. When in 1605 the Druze emir Fakhr al-Din Ma'n II took over Kesrewan, he entrusted its management to the Khazin Maronite family. The Khazins gradually colonized Kesrewan, purchasing Shia lands and founding churches and monasteries. They emerged as the predominant authority in the region at the expense of the Shia Hamedeh clan. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Khazins owned Kesrewan and only a few Shia villages survived.

During the time of the Ottoman Empire, the Shias suffered religious persecution and were often forced to flee their homes in search of refuge in the South. In response to the growth of Shiism, the Ottoman Empire put Shias to the sword in Anatolia. Hundreds of thousands of Shias were massacred in the Ottoman Empire, including the Alevis in Turkey, the Alawis in Syria and the Shi'a of Lebanon.[12] One example is the Lebanese city of Tripoli, which had formerly had a Shia Muslim majority. Many Lebanese Shia are rumored to have concealed their religious sect and acted as Sunni Muslims in fear of persecution. It is also rumored that some of the Shia permanently adopted the Sunni Muslim sect. The Ottomans and Druze were well allied and a Druze family seized power of Tripoli. Maronites who were persecuted by the Ottoman's and the Druze, sought refuge amongst the newly relocated Shia population in the South. Jezzine, once famously known as a Shia capital in Lebanon, is now known as a major Christian city in the South. The Shias withdrew further south and eventually had to abandon even Jezzine, which until the mid-eighteenth century had functioned as a center of Shia learning in Lebanon.[11] The traditional accounts of Shia "persecution" in Lebanon, however, which are largely based on family legends, are seriously called into question by the Ottoman documentation available in the state archives in Istanbul or local sharia archives in Tripoli. According to these, leading Shia families such as the Hamadas in Tripoli, the Harfushes in the Beqaa or the Ali al-Saghirs in Jabal 'Amil were co-opted into the Ottoman system of government, serving as tax farmers (multezim) over huge areas and enjoying other government offices (sancak-beylik governorships, etc.) in the region.[13]

Although the Jabal 'Amil enjoyed a degree of autonomy in the eighteenth century under the leader of the Ali al-Saghirs, Nasif al-Nassar, and the Arab leader of northern Palestine, Zahir al-Umar, this ended with the Ottoman appointment of Ahmad al-Jazzar as governor of Sidon province (1775–1804). Jazzar crushed the military power of the Shia clan leaders and burned the libraries of the religious scholars using the Druze tribes established in the Shouf, mainly the strong Nakad family, allied to the Maan. He established a centralized administration in the Shia areas and brought their revenues and cash crops under his domain. By the late eighteenth century, the Shias of the Jabal 'Amil lost their independent spirit and adopted an attitude of political defeat. Al-Jezzar was nicknamed "the butcher" and a big population of the Shia were killed under his rule in Lebanon.

Relations with Iranian Shias

During most of the Ottoman period, the Shia largely maintained themselves as 'a state apart', although they found common ground with their fellow Lebanese, the Maronites; this may have been due to the persecutions both sects faced. They maintained contact with the Safavid dynasty of Persia, where they helped establish Shia Islam as the state religion of Persia during the Safavid conversion of Iran from Sunnism to Shiism. Since most of the population embraced Sunni Islam and since an educated version of Shiism was scarce in Iran at the time, Ismail imported a new Shia Ulema corps from traditional Shiite centers of the Arabic speaking lands, such as Jabal Amil (of Southern Lebanon), Bahrain and Southern Iraq in order to create a state clergy. Ismail offered them land and money in return for loyalty. These scholars taught the doctrine of Twelver Shiism and made it accessible to the population and energetically encouraged conversion to Shiism.[14][15][16][17] To emphasize how scarce Twelver Shiism was then to be found in Iran, a chronicler tells us that only one Shia text could be found in Ismail's capital Tabriz.[18] Thus it is questionable whether Ismail and his followers could have succeeded in forcing a whole people to adopt a new faith without the support of the Arab Shiite scholars.[19]

These contacts further angered the Ottoman Sultan, who had already viewed them as religious heretics. The Sultan was frequently at war with the Persians, as well as being, in the role of Caliph, the leader of the majority Sunni community. Shia Lebanon, when not subject to political repression, was generally neglected, sinking further and further into the economic background. Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Comte de Volmy was to describe the Shia as a distinct society.

French mandate period

The Shias in Lebanon were the first to resist the French occupation. Following the creation of the French mandate, armed rebels led by Adham Khanjar and Sadiq Hamzeh attacked French positions in Southern Lebanon, including an unsuccessful attempt on French High Commissioner Henri Gouraud in which Khanjar was captured and later executed.[20]

Sub-groups

Shia Twelvers in Lebanon

Shia Twelvers in Lebanon refers to the Shia Muslim Twelver community with a significant presence in north Lebanon (Kesrawan and Batroun), the South Lebanon, the Beqaa and South Beirut suburbs.

The jurisdiction of the Ottoman Empire was merely nominal in the Lebanon. Baalbek in the 18th century was really under the control of the Metawali, which also refers to the Shia Twelvers.[21] Mutawili or mutawalli is also the name of a trustee in Islamic waqf-system.

Seven Shia Twelver (Metawali) villages that were reassigned from French Greater Lebanon to the British Mandate of Palestine in a 1924 border-redrawing agreement were depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and repopulated with Jews.[22] The seven villages are Qadas, Nabi Yusha, al-Malikiyya, Hunin, Tarbikha, Abil al-Qamh, and Saliha.[23]

In addition, the Shia Twelvers in Lebanon have close links to the Syrian Shia Twelvers.[24]

Alawites

There are an estimated 40,000 to 120,000[25][26][27] Alawites in Lebanon, where they have lived since at least the 16th century.[28] They are recognized as one of the 18 official Lebanese sects, and due to the efforts of their leader Ali Eid, the Taif Agreement of 1989 gave them two reserved seats in the Parliament. Lebanese Alawites live mostly in the Jabal Mohsen neighbourhood of Tripoli, and in 15 villages in the Akkar region,[29][30][31] and are mainly represented by the Arab Democratic Party. Bab al-Tabbaneh, Jabal Mohsen clashes between pro-Syrian Alawites and anti-Syrian Sunnis have haunted Tripoli for decades.[32]

Ismailis

Ismailism, or "Sevener Shi'ism", is a branch of Shia Islam which emerged in 765 from a disagreement over the succession to Muhammad. Ismailis hold that Isma'il ibn Jafar was the true seventh imam, and not Musa al-Kadhim as the Twelvers believe. Ismaili Shi'ism also differs doctrinally from Imami Shi'ism, having beliefs and practices that are more esoteric and maintaining seven pillars of faith rather than five pillars and ten ancillary precepts.

Though perhaps somewhat better established in neighbouring Syria, where the faith founded one of its first da'wah outposts in the city of Salamiyah (the supposed resting place of the Imam Isma'il) in the 8th century, it has been present in what is now Lebanon for centuries. Early Lebanese Ismailism showed perhaps an unusual propensity to foster radical movements within it, particularly in the areas of Wadi al-Taym, adjoining the Beqaa valley at the foot of Mount Hermon, and Jabal Shuf, in the highlands of Mount Lebanon.[33]

The syncretic beliefs of the Qarmatians, typically classed as an Ismaili splinter sect with Zoroastrian influences, spread into the area of the Beqaa valley and possibly also Jabal Shuf starting in the 9th century. The group soon became widely vilified in the Islamic world for its armed campaigns across throughout the following decades, which included slaughtering Muslim pilgrims and sacking Mecca and Medina—and Salamiyah. Other Muslim rulers soon acted to crush this powerful heretical movement. In the Levant, the Qarmatians were ordered to be stamped out by the ruling Fatimid, themselves Ismailis and from whom the lineage of the modern Nizari Aga Khan is claimed to descend. The Qarmatian movement in the Levant was largely extinguished by the turn of the millennium.[33]

The semi-divine personality of the Fatimid caliph in Ismailism was elevated further in the doctrines of a secretive group which began to venerate the caliph Hakim as the embodiment of divine unity. Unsuccessful in the imperial capital of Cairo, they began discreetly proselytising around the year 1017 among certain Arab tribes in the Levant. The Ismailis of Wadi al-Taym and Jabal Shuf were among those who converted before the movement was permanently closed off a few decades later to guard against outside prying by mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims, who often viewed their doctrines as heresy. This deeply esoteric group became known as the Druze, who in belief, practice, and history have long since become distinct from Ismailis proper. Druzes constitute 5% of the modern population of Lebanon and still have a strong demographic presence in their traditional regions within the country to this day.[33]

Due to official persecution by the Sunni Zengid dynasty that stoked escalating sectarian clashes with Sunnis, many Ismailis in the regions of Damascus and Aleppo are said to have fled west during the 12th century. Some settled in the mountains of Lebanon, while others settled further north along the coastal ridges in Syria,[34] where the Alawites had earlier taken refuge—and where their brethren in the Assassins were cultivating a fearsome reputation as they staved off armies of Crusaders and Sunnis alike for many years.

Once far more numerous and widespread in many areas now part of Lebanon, the Ismaili population has largely vanished over time. It has been suggested that Ottoman-era persecution might have spurred them to leave for elsewhere in the region, though there is no record or evidence of any kind of large exodus.[35]

Ismailis were originally included as one of five officially-defined Muslim sects in a 1936 edict issued by the French Mandate governing religious affairs in the territory of Greater Lebanon, alongside Sunnis, Twelver Shias, Alawites, and Druzes. However, Muslims collectively rejected being classified as divided, and so were left out of the law in the end. Ignored in a post-independence law passed in 1951 that defined only Judaism and Christian sects as official, Muslims continued under traditional Ottoman law, within the confines of which small communities like Ismailis and Alawites found it difficult to establish their own institutions.[36]

The Aga Khan IV made a brief stop in Beirut on 4 August 1957 while on a global tour of Nizari Ismaili centres, drawing an estimated 600 Syrian and Lebanese followers of the religion to the Beirut Airport in order to welcome him.[37] In the mid-1980s, several hundred Ismailis were thought to still live in a few communities scattered across several parts of Lebanon.[38] Though they are nominally counted among the 18 officially-recognised sects under modern Lebanese law,[39] they currently have no representation in state functions[40] and continue to lack personal status laws for their sect, which has led to increased conversions to established sects to avoid the perpetual inconveniences this produces.[41]

War in the region has also caused pressures on Lebanese Ismailis. In the 2006 Lebanon War, Israeli warplanes bombed the factory of the Maliban Glass company in the Beqaa valley on 19 July. The factory was bought in the late 1960s by the Madhvani Group under the direction of Ismaili entrepreneur Abdel-Hamid al-Fil after the Aga Khan personally brought the two into contact. It had expanded over the next few decades from an ailing relic to the largest glass manufacturer in the Levant, with 300 locally hired workers producing around 220,000 tons of glass per day. Al-Fil closed the plant down on 15 July just after the war broke out to safeguard against the deaths of workers in the event of such an attack, but the damage was estimated at a steep 55 million US dollars, with the reconstruction timeframe indefinite due to instability and government hesitation.[42]

Geographic distribution within Lebanon

Lebanese Shia Muslims are concentrated in the south Beirut and its southern suburbs, northern and western area of the Beqaa Valley, Southern Lebanon, Tripoli and Akkar region.[43]

Demographics

The last census in Lebanon in 1932 put the numbers of Shias at 20% of the population (155,000 of 791,700).[44] A study done by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1985 put the numbers of Shias at 41% of the population (919,000 of 2,228,000).[44]

According to another CIA study, the Shia Muslims constitutes 27% of Lebanons's population of approximately 4.3 million, which means they amount to 1,160,000 as of 2012.[1]

According to other sources, the Lebanese Shia Muslims have become the single largest religious community in Lebanon, constituting approximately 40 percent of the entire population (or 1.6 million out of a total population of 4 million).[2][4]

| Year | Shiite Population | Total Lebanese Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 154,208 | 785,543 | 19.6% |

| 1956 | 250,605 | 1,407,868 | 17.8% |

| 1975 | 668,500 | 2,550,000 | 26.2% |

| 1984 | 1,100,000 | 3,757,000 | 30.8% |

| 1988 | 1,325,000 | 4,044,784 | 32.8% |

| 2005 | 1,600,000 | 4,082,000 | 40% |

Notable people

|  |  |  |

- Musa al-Sadr – Spiritual leader and founder of the Amal movement

- Hussein el Husseini – Statesman, co-founder of the Amal movement and Speaker of Parliament

- Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah – Spiritual Leader

- Hassan Nasrallah – Leader of the group Hezbollah

- Nabih Berri – Speaker of the Parliament and political leader

- Sabri Hamade – Speaker of the Parliament and political leader

- Ragheb Alama – singer, composer, television personality, and philanthropist

- Amal Saad-Ghorayeb – Lebanese writer and scholar

- Ali Qanso – member of cabinet, former president of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party

- Diana Haddad – singer and television personality

- Bushra Khalil – Lebanese lawyer, represented Saddam Hussein during his trial

- Haifa Wehbe – model, actress, and singer

- Assi El Helani – Famous singer

- May Hariri – model, actress, and singer

- Alissar Caracalla – Lebanese Dance choreographer

- Okab Sakr – Lebanese journalist

- Mouhamed Harfouch - Brazilian-Lebanese actor

- Fouad Ajami - university professor and writer on Middle Eastern issues

- Rima Fakih – winner of the 2010 Miss USA title

These are notable Lebanese Shia Muslim families:

- Hamade clan (See Hamade) – Feudal lords (Sheikhs/شيوخ) and political family[45][46]

- Harfush- Feudal lords (Emir/أمير) and political family [47]

- Osseiran – Political dynasty

- Fadel – Feudal landowners

- Khalil – Feudal landowners

- Sabbah – Feudal landowners

- Yahfoufi – Prince descendant of hamadinds of Aleppo

See also

- Islam in Lebanon

- Maronite Christianity in Lebanon

- Eastern Orthodox Christianity in Lebanon

- Melkite Christianity in Lebanon

- Religion in Lebanon

- Sunni Islam in Lebanon

- Druze in Lebanon

- Banu Amela, Shia tribe in Lebanon

- Jabal Amel, region in Lebanon

References

- 1 2 3 4 "2012 Report on International Religious Freedom - Lebanon". United States Department of State. 20 May 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Yusri Hazran (June 2009). The Shiite Community in Lebanon: From Marginalization to Ascendancy (PDF). Brandeis University. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ David Levinson (1998). Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. Oryx Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-57356-019-1.

- 1 2 Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Group - David Levinson. Google Books. 1998. p. 249. ISBN 9781573560191. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ "Lebanon-Religious Sects". Global security.org. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ "March for secularism; religious laws are archaic". NOW News. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ "Fadlallah Charges Every Sect in Lebanon Except his Own Wants to Dominate the Country". Naharnet. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ "Aspects of Christian-Muslim Relations in Contemporary Lebanon". Macdonald.hartsem.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- ↑ Zalloua, Pierre A., Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon Is Structured by Recent Historical Events, The American Journal of Human Genetics 82, 873–882, April 2008

- 1 2 "Sample Chapter for Nakash, Y.: Reaching for Power: The Shi'a in the Modern Arab World". Press.princeton.edu. 1914-05-29. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ↑ Nasr (2006)p. 65-66

- ↑ Stefan Winter, The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788 (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- ↑ The failure of political Islam, By Olivier Roy, Carol Volk, pg.170

- ↑ The Cambridge illustrated history of the Islamic world, By Francis Robinson, pg.72

- ↑ The Middle East and Islamic world reader, By Marvin E. Gettleman, Stuart Schaar, pg.42

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern ... By Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer, pg.360

- ↑ Iran: religion, politics, and society : collected essays, By Nikki R. Keddie, pg.91

- ↑ Iran: a short history : from Islamization to the present, By Monika Gronke, pg.90

- ↑ In the Shadow of Sectarianism: Law, Shi`ism, and the Making of Modern Lebanon - Max Weiss. Google Books. 2010-10-30. p. 58. ISBN 9780674052987. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ "Lebanon (From Semitic laban", to be...". Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Danny Rubinstein (6 August 2006). "The Seven Lost Villages". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ Lamb, Franklin. Completing The Task Of Evicting Israel From Lebanon 2008-11-18.

- ↑ "Report: Hizbullah Training Shiite Syrians to Defend Villages against Rebels — Naharnet". naharnet.com. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑

- ↑ Riad Yazbeck. Return of the Pink Panthers?. Mideast Monitor. Vol. 3, No. 2, August 2008

- ↑ Zoi Constantine (2012-12-13). "Pressures in Syria affect Alawites in Lebanon - The National". Thenational.ae. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ↑ "'Lebanese Allawites welcome Syria's withdrawal as 'necessary' 2005, The Daily Star, 30 April". dailystar.com.lb. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

The Alawis have been present in modern-day Lebanon since the 16th century and are estimated to number 100,000 today, mostly in Akkar and Tripoli.

- ↑ Jackson Allers (22 November 2008). "The view from Jabal Mohsen". Menassat.com. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ "Lebanon: Displaced Allawis find little relief in impoverished north". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN). UNHCR. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ "Lebanon: Displaced families struggle on both sides of sectarian divide". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN). UNHCR. 31 July 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ David Enders (13 February 2012). "Syrian violence finds its echo in Lebanon". McClatchy Newspapers. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0520071964.

- ↑ Mahamid, Hatim (September 2006). "Isma'ili Da'wa and Politics in Fatimid Egypt." (PDF). Nebula. p. 13. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 137. ISBN 0520071964.

- ↑ "Lebanon – Religious Sects". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ↑ "FIRST VISIT TO FOLLOWERS". Ismaili.net. 4 August 1957. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ↑ Collelo, Thomas (1 January 2003). "Lebanon: A Country Study". In John C. Rolland. Lebanon: Current Issues and Background. Hauppage, NY: Nova Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 1590338715.

- ↑ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (27 July 2012). "International Religious Freedom Report for 2011" (PDF). United States Department of State. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ Khalaf, Mona Chemali (8 April 2010). "Lebanon". In Sanja Kelly and Julia Breslin. Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance (PDF). New York, NY: Freedom House. p. 10. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ "Lebanon 2008 - 2009: Towards a Citizen's State" (PDF). The National Human Development Report. United Nations Development Program. 1 June 2009. p. 70. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ Ohrstrom, Lysandra (2 August 2007). "War with Israel interrupts rare industrial success story". The Daily Star (Lebanon). Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ↑ Lebanon Ithna'ashari Shias Overview World Directory of Minorities. June 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Contemporary distribution of Lebanon's main religious groups". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- ↑ حمادة, سعدون (2008). تاريخ الشيعة في لبنان. دار الخيال للطباعة والنشر والتوزيع. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ "The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516-1788 - Book Reviews | Insight Turkey". insightturkey.com. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ Winter, S. (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9781139486811. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shia Muslims from Lebanon. |