Sima Qian

| Sima Qian | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born |

c. 145 or 135 BC Longmen, Han China (now Hejin, Shanxi) |

| Died | 86 BC |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for | Records of the Grand Historian |

| Relatives | Sima Tan (father) |

| Sima Qian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

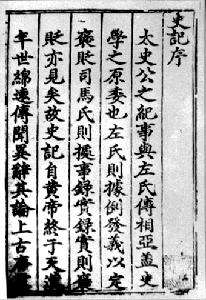

"Sima Qian" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 司馬遷 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 司马迁 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 子長 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 子长 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (courtesy name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sima Qian (pronounced [sɨ́mà tɕʰi̯ɛ́n]; c. 145 or 135 – 86 BC), formerly romanized Ssu-ma Chien, was a Chinese historian of the Han dynasty. He is considered the father of Chinese historiography for his Records of the Grand Historian, a Jizhuanti-style (history presented in a series of biographies) general history of China, covering more than two thousand years from the Yellow Emperor to his time, during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, a work that had much influence for centuries afterwards on history-writing not only in China, but in Korea, Japan and Vietnam as well.[1] Although he worked as the Court Astrologer (Chinese: 太史令; Tàishǐ Lìng), later generations refer to him as the Grand Historian (Chinese: 太史公; Tàishǐ Gōng or tai-shih-kung) for his monumental work; a work which in later generations would often only be somewhat tacitly or glancingly acknowledged as an achievement only made possible by his acceptance and endurance of punitive actions against him, including imprisonment, castration, and subjection to servility.

Early life and education

Sima Qian was born at Xiayang in Zuopingyi (near modern Hancheng, Shaanxi Province) around 145 BC, though some sources give his birth year as around 135 BC.[2] Sima's precise year of birth is still debated, but it is generally agreed that he lived most of his life during the reign of the Emperor Wu whose long reign lasted from 141-87 BC.[3] His father, Sima Tan, around 136 BC received an appointment to the relatively low-ranking position of "grand historian" (tàishǐ 太史, alt. "grand scribe" or "grand astrologer").[4][5] The grand historian's primary duty was to formulate the yearly calendar, identifying which days were ritually auspicious or inauspicious, and present it to the emperor prior to New Year's Day.[5] Besides these duties, the grand historian was also to travel with the emperor for important rituals and to record the daily events both at the court and within the country.[6] By his account, by the age of ten Sima was able to "read the old writings" and was considered to be a promising scholar.[6] Sima grew up in a family atmosphere strongly infused with Confucianism, and Sima always regarded his historical work as an act of Confucian filial piety to his beloved father.[6] The time that Sima grew up was a time of cultural flowering and economic growth in China with the empire expanding and the Silk Road linking the markets of China to the markets of Europe was opened.[7] With China flourishing, the young Sima shared in the general self-confident and optimistic atmosphere of the time.[8]

In 126 BC, around the age of twenty, Sima Qian began an extensive tour around China as it existed in the Han dynasty, and became probably one of the most widely traveled men of his generation.[5] He started his journey from the imperial capital, Chang'an (modern Xi'an), then went south across the Yangtze River to Changsha (modern Hunan Province), where he visited the Miluo River site where the ancient poet Qu Yuan was traditionally said to have drowned himself.[5] He then went to seek the burial place of the legendary Xia dynasty rulers Yu on Mount Kuaiji and Shun in the Jiuyi Mountains (modern Ningyuan County, Hunan).[5][9] He then went north to Huaiyin (modern Huai'an, Jiangsu Province) to see the grave of Han dynasty general Han Xin, then continued north to Qufu, the hometown of Confucius, where he studied ritual and other traditional subjects.[5]

As Han court official

After his travels, Sima was chosen to be a Palace Attendant in the government, whose duties were to inspect different parts of the country with Emperor Wu in 122 BC.[10] Sima married young and had one daughter.[11] In 110 BC, at the age of thirty-five, Sima Qian was sent westward on a military expedition against some "barbarian" tribes. That year, his father fell ill and could not attend the Imperial Feng Sacrifice. Suspecting his time was running out, he summoned his son back home to complete the historical work he had begun. Sima Tan wanted to follow the Annals of Spring and Autumn - the first chronicle in the history of Chinese literature. Fueled by his father's inspiration, Sima Qian started to compile Shiji, which became known in English as the Records of the Grand Historian, in 109 BC. Three years after the death of his father, Sima Qian assumed his father's previous position as Court Astrologer. In 105 BC, Sima was among the scholars chosen to reform the calendar. As a senior imperial official, Sima was also in the position to offer counsel to the emperor on general affairs of state.

The Li Ling affair

In 99 BC, Sima Qian became embroiled in the Li Ling affair, where Li Ling and Li Guangli, two military officers who led a campaign against the Xiongnu in the north, were defeated and taken captive. Emperor Wu attributed the defeat to Li Ling, with all government officials subsequently condemning him for it. Sima was the only person to defend Li Ling, who had never been his friend but whom he respected. Emperor Wu interpreted Sima's defence of Li as an attack on his brother-in-law, who had also fought against the Xiongnu without much success, and sentenced Sima to death. At that time, execution could be commuted either by money or castration. Since Sima did not have enough money to atone his "crime", he chose the latter and was then thrown into prison, where he endured three years. He described his pain thus: "When you see the jailer you abjectly touch the ground with your forehead. At the mere sight of his underlings you are seized with terror... Such ignominy can never be wiped away." Sima called his castration "the worst of all punishments".[6]

In 96 BC, on his release from prison, Sima chose to live on as a palace eunuch to complete his histories, rather than commit suicide as was expected of a gentleman-scholar who had been disgraced with castration.[12] As Sima Qian himself explained in his Letter to Ren An:

If even the lowest slave and scullion maid can bear to commit suicide, why should not one like myself be able to do what has to be done? But the reason I have not refused to bear these ills and have continued to live, dwelling in vileness and disgrace without taking my leave, is that I grieve that I have things in my heart which I have not been able to express fully, and I am shamed to think that after I am gone my writings will not be known to posterity. Too numerous to record are the men of ancient times who were rich and noble and whose names have yet vanished away. It is only those who were masterful and sure, the truly extraordinary men, who are still remembered. ... I too have ventured not to be modest but have entrusted myself to my useless writings. I have gathered up and brought together the old traditions of the world which were scattered and lost. I have examined the deeds and events of the past and investigated the principles behind their success and failure, their rise and decay, in one hundred and thirty chapters. I wished to examine into all that concerns heaven and man, to penetrate the changes of the past and present, completing all as the work of one family. But before I had finished my rough manuscript, I met with this calamity. It is because I regretted that it had not been completed that I submitted to the extreme penalty without rancor. When I have truly completed this work, I shall deposit it in the Famous Mountain. If it may be handed down to men who will appreciate it, and penetrate to the villages and great cities, then though I should suffer a thousand mutilations, what regret should I have?

As a eunuch, Sima had to attach a metal pipe to urinate and he spoke with the distinctive high-pitched voice of the castrated. Finally, Sima had to wear the traditional mark of a eunuch, namely he had to place his severed genitals in a jar of vinegar and wear it around his neck so that all might see his disgrace. Eunuchs often had much power in China, but the social prestige of eunuchs were extremely low, and Sima as someone who had lost the Emperor's favor was treated as an outcast by the elite.[14] Sima chose to go living to complete his history as out of sense of Confucian filial loyalty to his father and to vindicate himself and wipe away his disgrace.[15]

"The Grand Historian"

Although the style and form of Chinese historical writings varied through the ages, the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) has defined the quality and style from then onwards. Before Sima, histories were written as certain events or certain periods of history of states; his idea of a general history affected later historiographers like Zheng Qiao (郑樵) in writing Tongshi (通史) and Sima Guang in writing Zizhi Tongjian. The Chinese historical form of dynasty history, or jizhuanti history of dynasties, was codified in the second dynastic history by Ban Gu's Book of Han, but historians regard Sima's work as their model, which stands as the "official format" of the history of China. The Shiji comprises 130 chapters consisting of half-million characters.[16]

Sima was greatly influenced by Confucius’s Spring and Autumn Annals, which on the surface is a succinct chronology from the events of the reigns of the twelve dukes of Lu from 722 to 484 BC.[6] Many Chinese scholars have and still do view how Confucius ordered his chronology as the ideal example of how history should be written, especially with regards to what he chose to include and to exclude; and his choice of words as indicating moral judgements [6] Seen in this light, the Spring and Autumn Annals are a moral guide to the proper way of living.[17] Sima took this view himself as he explained:

It [Spring and Autumn Annals] distinguishes what is suspicious and doubtful, clarifies right and wrong, and settles points which are uncertain. It calls good good and bad bad, honours the worthy, and condemns the unworthy. It preserves states which are lost and restores the perishing family. It brings to light what was neglected and restores what was abandoned. [17]

Sima saw the Shiji as being in the same tradition as he explained in his introduction to chapter 61 of the Shiji where he wrote:

“Some people say 'It is Heaven’s way, without distinction of persons, to keep the good perpetually supplied. ' Can we say then that Po I and Shu Ch'I were good men or not? They clung to righteousness and were pure in their deeds…yet they starved to death…Robber Chih day after day killed innocent men, making mincemeat of their flesh…But in the end he lived to a great old age. For what virtue did he deserve this? …I find myself in much perplexity. Is this so-called 'Way of Heaven' right or wrong?”[17]

To resolve this theodical problem, Sima argued that while the wicked may succeed and the good may suffer in their own life-times, it is the historian who ensures that in the end good triumphs.[17] For Sima, the writing of history was no mere antiquarian pursuit, but was rather a vital moral task as the historian would “preserve memory”, and thereby ensure the ultimate victory of good over evil.[17] Along these lines, Sima wrote:

“Su Ch’in and his two brothers all achieved fame among the feudal lords as itinerant strategists. Their policies laid great stress upon stratagems and shifts of power. But because Su Ch’in died a traitor’s death, the world has united in scoffing at him and has been loath to study his policies…Su Ch’in arouse from the humblest beginnings to lead the Six States in the Vertical Alliance, and this is evidence that he possessed an intelligence surpassing the ordinary person. For this reason I have set forth this account of his deeds, arranging them in proper chronological order, so that he may not forever suffer from an evil reputation and be known for nothing else”.[18]

Such a moralizing approach to history with the historian high-guiding the good and evil to provide lessons for the present could be dangerous for the historian as it could bring down the wrath of the state onto to the historian as happened to Sima himself. As such, the historian had to tread carefully and often expressed his judgements in a circuitous way designed to fool the censor.[19]

Sima himself in the conclusion to chapter 110 of the Shiji declared that he was a writing in this tradition where he stated:

“When Confucius wrote the Spring and Autumn Annals, he was very open in treating the reigns of Yin and Huan, the early dukes of Lu; but when he came to the later period of Dukes Ding and Ai, his writing was much more covert. Because in the latter case he was writing about his own times, he did not express his judgements frankly, but used subtle and guarded language.”[19]

Bearing this in mind, not everything that Sima wrote should be understood as conveying didactical moral lessons.[19] But several historians have suggested that parts of the Shiji, such as where Sima placed his section on Confucius’s use of indirect criticism in the part of the book dealing with the Xiongnu “barbarians” might indicate his disapproval of the foreign policy of the Emperor Wu.[19]

In writing Shiji, Sima initiated a new writing style by presenting history in a series of biographies. His work extends over 130 chapters — not in historical sequence, but divided into particular subjects, including annals, chronicles, and treatises — on music, ceremonies, calendars, religion, economics, and extended biographies. Sima's work influenced the writing style of other histories outside of China as well, such as the Goryeo (Korean) history the Samguk Sagi. Sima adopted a new method in sorting out the historical data and a new approach to writing historical records. At the beginning of the Shiji, Sima declared himself a follower of Confucius’s approach in the Analects to “hear much but leave to one side that which is doubtful, and speak with due caution concerning the remainder”.[19] Reflecting these rigorous analytic methods, Sima declared that he would not write about periods of history where they was insufficient documentation.[19] As such, Sima wrote “the ages before the Ch’in dynasty are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here”.[19] In the same way, Sima discounted accounts in the traditional records that were “ridiculous” such as the pretense that Prince Tan could via the use of magic make the clouds rain grain and horses grow horns.[19] Sima constantly compared accounts found in the manuscripts with what he considered reliable sources like Confucian classics like the Book of Odes, Book of History, Book of Rites, Book of Music, Book of Changes and Spring and Autumn Annals.[19] When Sima encountered a story that could not be cross-checked with the Confucian classics, he systemically compared the information with other documents. Sima mentioned at least 75 books he used for cross-checking.[20] Furthermore, Sima often questioned people about historical events they had experienced.[19] Sima mentioned after one of his trips across China that: “When I had occasion to pass through Feng and Beiyi questioned the elderly people who were about the place, visited the old home of Xiao He, Cao Can, Fan Kuai and Xiahou Ying, and learned much about the early days. How different it was from the stories one hears!”[20] Reflecting the traditional Chinese reverence for age, Sima stated that he preferred to interview the elderly as he believed that they were the most likely to supply him with correct and truthful information about had happened in the past.[20] During one of this trips, Sima mentioned that he was overcome with emotion when he saw the carriage of Confucius together with his clothes and various other personal items that had belonged to Confucius.[20]

Despite his very large debts to Confucian tradition, Sima was an innovator in four ways. To begin with, Sima’s work was concerned with the history of the known world.[20] Previous Chinese historians had only focused on only one dynasty and/or region. [20] Sima’s history of 130 chapters began with the legendary Yellow Emperor to his own time, and covered not only China, but also neighboring nations like Korea and Vietnam.[20] In this regard, Sima was significant as the first Chinese historian to treat the peoples living to the north of the Great Wall like the Xiongnu as human beings who were implicitly the equals of the Middle Kingdom, instead of the traditional approach which had portrayed the Xiongnu as savages who had the appearance of humans, but the minds of animals.[21] In his comments about the Xiongnu, Sima refrained from evoking claims about the innate moral superiority of the Han over the "northern barbarians" that were the standard rhetorical tropes of Chinese historians in this period.[22] Likewise, Sima in his chapter about the Xiongnu condemns those advisors who purse the "expediency of the moment", that is advise the Emperor to carry policies such as conquests of other nations that bring a brief moment of glory, but burden the state with the enormous financial and often human costs of holding on to the conquered land.[23] Sima was engaging in an indirect criticism of the advisors of the Emperor Wu who were urging him to pursue a policy of aggression towards the Xiongnu and conquer all their land, a policy that Sima was apparently opposed to.[24]

Sima also broke new ground by using more sources like interviewing witnesses, visiting places where historical occurrences had happened, and examining documents from different regions and/or times.[20] Before Chinese historians had tended to use only reign histories as their sources.[20] The Shiji was further very novel in Chinese historiography by examining historical events outside of the courts, providing a broader history than the traditional court-based histories had done.[20] Lastly, Sima broke with the traditional chronological structure of Chinese history. Sima instead had divided the Shiji into five divisions: the basic annals which comprised the first 12 chapters, the chronological tables which comprised the next 10 chapters, treatises on particular subjects which make up 8 chapters, accounts of the ruling families which take up 30 chapters, and biographies of various eminent people which are the last 70 chapters.[20] The annals follow the traditional Chinese pattern of court-based histories of the lives of various emperors and their families.[20] The chronological tables are graphs recounting the political history of China.[20] The treatises are essays on topics such as astronomy, music, religion, hydraulic engineering and economics.[20] The last section dealing with biographies cover both famous people, both Chinese and foreign.[20] Unlike traditional Chinese historians, Sima went beyond the androcentric, emperor-focused histories by dealing with the lives of women and men such as poets, bureaucrats, merchants, assassins, and philosophers.[25] The treatises section, the biographies sections and the annals section relating to the Qin dynasty (as a former dynasty, there was more freedom to write about the Qin than there was about the reigning Han dynasty) that make up 40% of the Shiji have aroused the most interest from historians and are the only parts of the Shiji that have been translated into English.[26]

When Sima placed his subjects was often his way of expressing obliquely moral judgements.[25] Empress Lü and Xiang Yu were the effective rulers of China during reigns Hui of the Han and Yi of Chu respectively, so Sima placed both their lives in the basic annals.[25] Likewise, Confucius is included in the fourth section rather the fifth where he properly belonged as a way of showing his eminent virtue.[25] The structure of the Shiji allowed Sima to tell the same stories in different ways, which allowed him to pass his moral judgements.[25] For example, in the basic annals section, the Emperor Gaozu is portrayed as a good leader whereas in the section dealing with his rival Xiang Yu, the Emperor is portrayed unflatteringly.[25] Likewise, the chapter on Xiang presents him in a favorable light whereas the chapter on Gaozu portrays him in more darker colors.[25] At the end of most of the chapters, Sima usually wrote a commentary in which he judged how the individual lived up to traditional Chinese values like filial piety, humility, self-discipline, hard work and concern for the less fortunate.[25] Sima analyzed the records and sorted out those that could serve the purpose of Shiji. He intended to discover the patterns and principles of the development of human history. Sima also emphasized, for the first time in Chinese history, the role of individual men in affecting the historical development of China and his historical perception that a country cannot escape from the fate of growth and decay.

Unlike the Book of Han, which was written under the supervision of the imperial dynasty, Shiji was a privately written history since he refused to write Shiji as an official history covering only those of high rank. The work also covers people of the lower classes and is therefore considered a "veritable record" of the darker side of the dynasty. In Sima's time, literature and history were not seen as separate disciplines as they are now, and Sima wrote his magnum opus in a very literary style, making extensive use of irony, sarcasm, juxtaposition of events, characterization, direct speech and invented speeches, which led the American historian Jennifer Jay to describe parts of the Shiji as reading more like a historical novel than a work of history.[27] For an example, Sima tells the story of a Chinese eunuch named Zhonghang Xue who become an advisor to the Xiongnu kings.[28] Sima provides a long dialogue between Zhonghang and an envoy sent by the Emperor Wen of China during which the latter disparages the Xiongnu as "savages" whose customs are barbaric while Zhonghang defends the Xiongnu customs as either justified and/or as morally equal to Chinese customs, at times even morally superior as Zhonghang draws a contrast between the bloody succession struggles in China where family members would murder one another to be Emperor vs. the more orderly succession of the Xiongnu kings.[29] The American historian Tamara Chin wrote that through Zhonghang did exist, the dialogue is merely a "literacy device" for Sima to make points that he could not otherwise make.[30] The favorable picture of the traitor Zhonghang who went over to the Xiongnu who bests the Emperor's loyal envoy in an ethnographic argument about what is the morally superior nation appears to be Sima's way of attacking the entire Chinese court system where the Emperor preferred the lies told by his sycophantic advisors over the truth told by his honest advisors as inherently corrupt and depraved.[31] The point is reinforced by the fact that Sima has Zhonghang speak the language of an idealized Confucian official whereas the Emperor's envoy's language is dismissed as "mere twittering and chatter".[32] Elsewhere in the Shiji Sima portrayed the Xiongnu less favorably, so the debate was most almost certainly more Sima's way of criticizing the Chinese court system and less genuine praise for the Xiongnu.[33]

Sima has often been criticized for "historizing" myths and legends as he assigned dates to mythical and legendary figures from ancient Chinese history together with what appears to be suspiciously precise genealogies of leading families over the course of several millennia (including his own where he traces the descent of the Sima family from legendary emperors in the distant past).[34] However, archaeological discoveries in recent decades have confirmed aspects of the Shiji, and suggested that even if the sections of the Shiji dealing with the ancient past are not totally true, that at least Sima wrote down what he believed to be true.[35] In particular, archaeological finds have confirmed the basic accuracy of the Shiji including the reigns and locations of tombs of ancient rulers.[36]

Literary figure

Sima's Shiji is respected as a model of biographical literature with high literary value and still stands as a textbook for the study of classical Chinese. Sima's works were influential to Chinese writing, serving as ideal models for various types of prose within the neo-classical ("renaissance" 复古) movement of the Tang-Song period. The great use of characterisation and plotting also influenced fiction writing, including the classical short stories of the middle and late medieval period (Tang-Ming) as well as the vernacular novel of the late imperial period. Sima had immense influence on historiography not only in China, but also in Japan and Korea. [37] For centuries afterwards, the Shiji was regarded as the greatest history book written in Asia. [37] Sima is little known in the English-speaking world as a full translation of the Shiji has never been attempted. [37]

His influence was derived primarily from the following elements of his writing: his skillful depiction of historical characters using details of their speech, conversations, and actions; his innovative use of informal, humorous, and varied language; and the simplicity and conciseness of his style. Even the 20th century literary critic Lu Xun regarded Shiji as "the historians' most perfect song, a "Li Sao" without the rhyme" (史家之绝唱,无韵之离骚) in his "Hanwenxueshi Gangyao" (汉文学史纲要).

Other literary works

Sima's famous letter to his friend Ren An about his sufferings during the Li Ling Affair and his perseverance in writing Shiji is today regarded as a highly admired example of literary prose style, studied widely in China even today.

Sima Qian wrote eight rhapsodies (fu 赋), which are listed in the bibliographic treatise of the Book of Han. All but one, the "Rhapsody in Lament for Gentleman who do not Meet their Time" (士不遇赋) have been lost, and even the surviving example is probably not complete.

Astrologer

Sima and his father were both court astrologers (taishi) 太史 in the Former Han Dynasty. At that time, the astrologer had an important role, responsible for interpreting and predicting the course of government according to the influence of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as other phenomena such as solar eclipses and earthquakes.

Before compiling Shiji, in 104 BC, Sima Qian created Taichuli (太初历) which can be translated as 'The first calendar' on the basis of the Qin calendar. Taichuli was one of the most advanced calendars of the time. The creation of Taichuli was regarded as a revolution in the Chinese calendar tradition, as it stated that there were 365.25 days in a year and 29.53 days in a month.

The minor planet 12620 Simaqian is named in his honour.

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1093.

- ↑ Knechtges (2014), p. 959.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1093.

- ↑ de Crespigny (2007), p. 1222.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Knechtges (2014), p. 960.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 291.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1093.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1093.

- ↑ Watson (1958), p. 47.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Watson (1958), pp. 57-67.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 292.

- ↑ Hughes-Warrington (2000), pp. 292-293.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 293.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 294.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 pages 318-319.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 320.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 321.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 321.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 295.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 325.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 pages 325-326.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 pages 328-329.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 pages 333-334.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 334.

- ↑ Chin, Tamara "Defamiliarizing the Foreigner: Sima Qian's Ethnography and Han-Xiongnu Marriage Diplomacy" pages 311-354 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 70, Issue # 2, December 2010 page 340.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- ↑ Jay, Jennifer "Sima Qian" pages 1093-1094 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, Volume 2 edited by Kelly Boyd, Chicago: FitzRoy Dearborn, 1999 page 1094.

- 1 2 3 Hughes-Warrington (2000), p. 296.

- Works cited

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Hughes-Warrington, Marnie (2000). Fifty Key Thinkers on History. London: Routledge.

- Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Sima Qian 司馬遷". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Tai-ping. Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Two. Leiden: Brill. pp. 959–965. ISBN 978-90-04-19240-9.

- Watson, Burton (1958). Ssu-ma Ch'ien: Grand Historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Further reading

- Markley, J. Peace and Peril. Sima Qian's portrayal of Han - Xiongnu relations (Silk Road Studies XIII), Turnhout, 2016, ISBN 978-2-503-53083-3

- Allen, J.R "An Introductory Study of Narrative Structure in the Shi ji" pages 31–61 from Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, Volume 3, Issue 1, 1981.

- Allen, J.R. "Records of the Historian" pages 259–271 from Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective: A Guide for Teaching, Armonk: Sharpe, 1994.

- Beasley, W. G & Pulleyblank, E. G Historians of China and Japan, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961.

- Dubs, H.H. "History and Historians under the Han" pages 213-218 from Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 20, Issue # 2, 1961.

- Durrant S.W "Self as the Intersection of Tradition: The Autobiographical Writings of Ssu-Ch'ien" pages 33–40 from Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 106, Issue # 1, 1986.

- Cardner, C. S Traditional Historiography, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Hardy, G.R "Can an Ancient Chinese historian Contribute to Modern Western Theory?" pages 20–38 from History and Theory, Volume 33, Issue # 1, 1994.

- Kroll, J.L "Ssu-ma Ch'ien Literary Theory and Literary Practice" pages 313-325 from Altorientalische Forshungen, Volume 4, 1976.

- Li, W.Y "The Idea of Authority in the Shi chi" pages 345-405 from Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 54, Issue # 2, 1994.

- Moloughney, B. "From Biographical History to Historical Biography: A Transformation in Chinese Historical Writings" pages 1–30 from East Asian History, Volume 4, Issue 1, 1992.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sima Qian |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Works by Sima Qian at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sima Qian at Internet Archive

- Works by Sima Qian at Open Library

- Significance of Shiji on literature

- Sima Qian: China's 'grand historian', article by Carrie Gracie in BBC News Magazine, 7 October 2012

.svg.png)