John Tenniel

| Sir John Tenniel | |

|---|---|

|

Self-portrait of John Tenniel, c. 1889 | |

| Born |

27 July 1819 Bayswater, Middlesex, London, England |

| Died |

25 February 1914 (aged 93) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Illustration, Children's literature, Political cartoons |

Sir John Tenniel (27 July 1819[1] – 25 February 1914) was an English illustrator, graphic humourist, and political cartoonist whose work was prominent during the second half of the 19th century. Tenniel was knighted by Victoria for his artistic achievements in 1893.

Tenniel is most noted for being the principal political cartoonist for Britain's Punch magazine for more than 50 years, and he was the artist who illustrated Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871).

Early life

Tenniel was born in Bayswater, West London, to John Baptist Tenniel and Eliza Maria Tenniel. Tenniel had five siblings; two brothers and three sisters. One sister, Mary, was later to marry Thomas Goodwin Green, owner of the pottery that produced Cornishware. Tenniel was a quiet and introverted person, both as a boy and as an adult. He was content to remain firmly out of the limelight and seemed unaffected by competition or change. His biographer Rodney Engen wrote that Tenniel's "life and career was that of the supreme gentlemanly outside, living on the edge of respectability."[2]

In 1840 Tenniel, while practising fencing with his father, received a serious eye wound from his father's foil, which had accidentally lost its protective tip. Over the years Tenniel gradually lost sight in his right eye;[3] he never told his father of the severity of the wound, as he did not wish to upset his father further.

In spite of his tendency towards high art, Tenniel was already known and appreciated as a humorist and his early companionship with Charles Keene fostered and developed his talent for scholarly caricature.

Training

Tenniel became a student of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1842 by probation—he was admitted because he made several copies of classical sculptures to provide the necessary admission portfolio. So, it was here that Tenniel returned to his earlier independent education. While Tenniel's more formal training at the Royal Academy and at other institutions was beneficial in nurturing his artistic ambitions, it failed in Tenniel's mind because he disagreed with the school's teaching methods, resulting in Tenniel educating himself for his career. Tenniel studied classical sculptures through painting; however, Tenniel was frustrated that he was never taught how to draw.[4] Tenniel would draw the classical statues at the London's Townley Gallery, copied illustrations from books of costumes and armor in the British museum, and drew the animals from the zoo in Regent's Park as well as the actors from the London theatres, which were drawn from the pits.[5] It was in these studies that Tenniel learned to love detail; however, he became impatient with his work and was the happiest when he could draw from memory. Tenniel was blessed with a photographic memory, undermining his early training and seriously restricting his artistic ambitions.[6]

Another "formal" means of training was Tenniel's participation in an artists group, free from the rules of the academy that stifled Tenniel. In the mid-1840s Tenniel joined the Artist's Society or Clipstone Street Life Academy, and it could be said here that Tenniel first emerged as a satirical draftsman.[7]

Early career

Tenniel's first book illustration was for Samuel Carter Hall's The Book of British Ballads, in 1842.[8] While engaged with his first book illustrations, various contests were taking place in London, as a way in which the government could combat the growing Germanic Nazarenes style and promote a truly national English school of art. Tenniel planned to enter the 1845 House of Lords competition amongst artists to win the opportunity to design the mural decoration of the new Palace of Westminster.[9] Despite missing the deadline, he submitted a 16-foot (4.9 m) cartoon, An Allegory of Justice, to a competition for designs for the mural decoration of the new Palace of Westminster. For this he received a £200 premium and a commission to paint a fresco in the Upper Waiting Hall (or Hall of Poets) in the House of Lords.[10]

Political cartoons at Punch

As the influential result of his position as the chief cartoon artist for Punch (published 1841–1992, 1996–2002), John Tenniel, through satirical, often radical and at times vitriolic images of the world, for five decades was and remained Great Britain's steadfast social witness to the sweeping national changes in that nation's moment of political and social reform. At Christmas 1850 he was invited by Mark Lemon to fill the position of joint cartoonist (with John Leech) on Punch. He had been selected on the strength of his recent illustrations to Aesop's Fables. He contributed his first drawing in the initial letter appearing on p. 224, vol. xix. His first cartoon was Lord Jack the Giant Killer, which showed Lord John Russell assailing Cardinal Wiseman.

In 1861, Tenniel was offered John Leech's position at Punch, as political cartoonist; however, Tenniel still maintained some sense of decorum and restraint into the heated social and political issues of the day.[11]

Because his task was to construct the willful choices of his Punch editors, who probably took their cue from The Times and would have felt the suggestions of political tensions from Parliament as well, Tenniel's work, as was its design, could be scathing in effect. The restlessness of the Victorian period's issues of working class radicalism, labor, war, economy, and other national themes were the targets of Punch, which in turn commanded the nature of Tenniel's subjects. Tenniel's cartoons published in the 1860s made popular the portrait of the Irishman as a subhuman being, wanton in his appetites and most resembling an orangutan in both facial features and posture.[12] Many of Tenniel's political cartoons expressed strong hostility to Irish Nationalism, with Fenians and Land leagues depicted as monstrous, ape-like brutes, while "Hibernia"—the personification of Ireland—was depicted as a beautiful, helpless young girl threatened by these "monsters" and turning for protection to "her elder sister", the powerful armoured Britannia.

"An Unequal Match", his drawing published in Punch on 8 October 1881, depicted a police officer fighting a criminal with only a 'baton' for protection, trying to put a point across to the public that policing methods needed to be changed.

When examined separately from the book illustrations he did over time, Tenniel's work at Punch alone, expressing decades of editorial viewpoints, often controversial and socially sensitive, was created to echo the voices of the British public. Tenniel drew 2,165 cartoons for Punch, a liberal and politically active publication that mirrored the Victorian public's mood for liberal social changes; thus Tenniel, in his cartoons, represented for years the conscience of the British majority.

In his career Tenniel contributed around 2,300 cartoons, innumerable minor drawings, many double-page cartoons for Punch's Almanac and other special numbers, and 250 designs for Punch's Pocket-books. By 1866 he was "able to command ten to fifteen guineas for the reworking of a single Punch cartoon as a pencil sketch", alongside his "comfortable" Punch salary "of about £800 a year".[13] According to the Bank of England inflation calculator,[14] £800 in 1866 would buy goods and services worth over £85,000 in 2015 (with inflation averaged at 3.1% a year).

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass

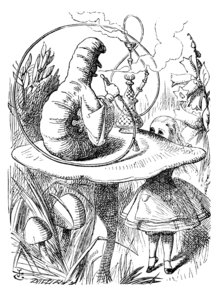

Despite the thousands of political cartoons and hundreds of illustrative works attributed to him, much of Tenniel's fame stems from his illustrations for Alice. Tenniel drew ninety-two drawings for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (London: Macmillan, 1865) and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (London: Macmillan, 1871).

Lewis Carroll originally illustrated "Wonderland" himself, but his artistic abilities were limited. Engraver Orlando Jewitt, who had worked for Carroll in 1859 and had reviewed Carroll's drawings for Wonderland, suggested that he employ a professional illustrator. Carroll was a regular reader of Punch and was therefore familiar with Tenniel. In 1865 Tenniel, after long talks with Carroll, illustrated the first edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

The first print run of 2,000 was sold in the United States, rather than England, because Tenniel objected to the print quality.[15] A new edition was released in December 1865, carrying an 1866 date, and became an instant best-seller, increasing Tenniel's fame. His drawings for both books have become some of the most famous literary illustrations. After 1872, when the Carroll projects were finished, Tenniel largely abandoned literary illustration. Carroll did later approach Tenniel to undertake another project for him. To this Tenniel replied:

It is a curious fact that with "Looking-Glass" the faculty of making drawings for book illustrations departed from me, and [...] I have done nothing in that direction since.[16]

Tenniel's illustrations for the Alice books were engraved onto blocks of deal wood by the Brothers Dalziel. These engravings were then used as masters for making the electrotype copies for the actual printing of the books.[17] The original wood blocks are held in the collection of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. They are not usually on public display, but were exhibited in 2003.

Style

Influence from the German Nazarenes

The style associated with the Nazarene movement of the nineteenth century influenced many subsequent artists including Tenniel. This style can be characterized as "shaded outlines" where the lines on the side of figures or objects are given extra thickness or are drawn as double lines in order to suggest shading or volume.[18] Additionally, this style is extremely precise, with the artist making a hard clear outline along its figures, creating dignified figures and compositions, as well as a restraint in expression and paleness of tone.[19] While Tenniel's early illustrations done in the Nazarene style were not well received, his encounter with the style pointed him in the right direction.[20]

An eye for detail

After the 1850s, Tenniel's style modernized to incorporate more detail in backgrounds and in figures. The inclusion of background details corrected the previously weak Germanic staging of his illustrations. Tenniel's more precisely-designed illustrations depicted specific moments of time, locale, and individual character instead of just generalized scenes.[21]

In addition to a change in specificity of background, Tenniel developed a new interest in human types, expressions, and individualized representation, something that would carry over into Tenniel's illustrations of Wonderland. Referred to by many as theatricalism, this hallmark of Tenniel's style probably stemmed from his earlier interest in caricature. In Tenniel's first years on Punch he developed this caricaturist's interest in the uniqueness of persons and things, almost giving a human like personality to the objects in the environment.[22] For example, in a comparison to one of John Everett Millais's illustration of a girl in a chair with Tenniel's illustration of Alice in a chair, one can see how where Millais's chair is just a prop, Tenniel's chair possesses a menacing and towering presence.

Another change in style was his shaded lines. These transformed from mechanical horizontal lines to vigorously hand-drawn hatching that greatly intensified darker areas.

Grotesque

Tenniel's "grotesqueness" was one of the main reasons why Lewis Carroll wanted Tenniel as his illustrator for the Alice books. The grotesque is an abnormality that imparts the disturbing sense that the real world may have ceased to be reliable.[23] Tenniel's style was characteristically grotesque in his dark atmospheric compositions of exaggerated fantasy creatures that were carefully drawn in outline.[24] Often though, the mechanism was to use animal heads on recognizable human bodies or vice versa, as Grandville had done with such effect in the pages of the Parisian satirical journal, Charivari.[25] In Tenniel's illustrations, the grotesque is found also in the merging of beings and things, deformities of and violence to the human body (as seen in the illustration when Alice drinks the potion and gets large), a proclivity to deal with the ordinary things of this world while exhibiting such phenomena.[23] Most notably done in grotesque fashion is that of Tenniel's famous Jabberwock drawing in Alice.

What is so fascinating and why so effective are the Alice illustrations is their ability to combine the fantasy and the real. Scholars such as Morris say that Tenniel's stylistic change can be attributed to the late 1850s trend towards realism. For the grotesque to operate, "it is our world which has to be transformed and not some fantasy realm."[26] In the illustrations we are constantly but subtly reminded of the real world, such as some of Tenniel's scenes being derived from a medieval town, the portico of Georgian town, or the checked jacket on the white rabbit. Additionally, Tenniel closely follows the text provided by Carroll so readers are ensured that what they are reading, they are seeing in his illustrations.[26] These subtle points of realism help convince readers that all these seemingly grotesque habitants of Wonderland are simply themselves, are simply real, they are not performing.

Image and Text Relationship in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

One of the most unusual elements of the Alice books is the placement of Tenniel's illustrations on the pages. There was a physical relation of the illustrations to the text, intended to subtly mesh illustrations with certain points of the text.[27] Carroll and Tenniel expressed this in various ways; one of them bracketing. Two relevant sentences would bracket an image, which might better define the moment that Tenniel was trying to illustrate.[28] It is this precise bracketing of Tenniel's pictures by the text that adds to their "dramatic immediacy."[28] However, other illustrations work with the texts in that they act as captions, though it is not as frequent as bracketing.

Another way in which the illustrations correspond with the text is by having broader and narrower illustrations. Broader illustrations are meant to be centered on the page, where as narrower illustrations are meant to be "let in" or run flush to the margin to be set alongside a narrowed column of the continuing text.[28] Still, words run in parallel with the depiction of those things. For example, in this image, we see how when Alice says, "Oh, my poor little feet," it not only occurs at the foot of the page but is directly next to her feet in the illustration. Part of these narrower illustrations was the "L" shaped illustration, which was of great importance, being that these are where Tenniel did some of his most memorable work. The top or base of these illustrations run the full width of the page but then the other end would has some room on one side of the quadrant for the text.[29]

Retirement and death

An ultimate tribute came to an elderly Tenniel as he was knighted for his public service in 1893 by Queen Victoria. It was the first such honour ever bequeathed on an illustrator or cartoonist, and his fellows saw his knighting as gratitude for "raising what had been a fairly lowly profession to an unprecedented level of respectability." With knighthood, Tenniel elevated the social status of the black and white illustrator, and sparked a new sense of recognition of his profession. When he retired in January 1901, Tenniel was honoured with a farewell banquet (12 June), at which AJ Balfour, then Leader of the House of Commons, presided.

Tenniel died in 1914 at the age of 94.

Legacy

Punch historian M. H. Spielmann, who knew Tenniel, wrote that the political clout contained in his Punch cartoons was capable of "swaying parties and people, too... (the cartoons) exercised great influence" on the ideas of popular reform skirting throughout the British public. Two days after his death, the Daily Graphic recalled Tenniel: "He had an influence on the political feeling of this time which is hardly measurable...While Tenniel was drawing them (his subjects), we always looked to the Punch cartoon to crystallize the national and international situation, and the popular feeling about it—and never looked in vain."[30] This condition of social influence resulted from the weekly publishing over a fifty-year span of his political cartoons, whereby Tenniel's fame allowed for a want and need for his particular illustrative work, away from the newspaper. Tenniel became not only one of Victorian Britain's most published illustrators, but as a Punch cartoonist he became one of the "supreme social observers" of British society, and an integral component of a powerful journalistic force. Also in 1914, the New York Tribune journalist George W. Smalley referred to John Tenniel as "one of the greatest intellectual forces of his time, (who) understood social laws and political energies."

Public exhibitions of Sir John Tenniel's work were held in 1895 and in 1900. Sir John Tenniel is also the author of one of the mosaics, Leonardo da Vinci, in the South Court in the Victoria and Albert Museum; while his highly stippled watercolour drawings appeared from time to time in the exhibitions of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, of which he had been elected a member in 1874.

A Bayswater street, Tenniel Close,[31] near his former studio, is named after him.[32]

Works

|

Illustrated by Tenniel:

|

Illustrated by Tenniel in collaboration:

|

He also contributed to Once a Week, the Art Union publications, etc.

Gallery

-

Alice playing with the puppy

-

The Jabberwock, as illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, including the poem "Jabberwocky".

-

"Davy Jones' Locker", 1892 Punch cartoon

-

"Dropping the Pilot", 1890 Punch cartoon commenting on Otto von Bismarck's dismissal

-

"The Nemesis of Neglect", 1888 Punch cartoon commenting on the Jack the Ripper murders

References

- ↑ "John Tenniel", London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813–1906, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Board of Guardian Records, 1834–1906 and Church of England Parish Registers, 1754–1906, London Metropolitan Archives, London.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 1.

- ↑ Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice, p. 223

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 35.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 36.

- ↑ The complex history surrounding the decoration is best summarized by T. S. R. Boase, The Decorations of the New Palace of Westminster 1841-1863, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 17:1954, pp. 319–358.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 46.

- ↑ Davison, Neil (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Simpson, Roger (1994). Sir John Tenniel: Aspects of His Work. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780838634936. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Inflation Calculator". Bank of England. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Gladstone and Elwyn-Jones, 1998, pages 253-255.

- ↑ See Michael Hancher's essay, "Carroll and Tenniel in Collaboration," The Tenniel Illustrations to the Alice Books: 105

- ↑ "About Tenniel". Sir John Tenniel's Alice in Wonderland. GoldmarkArt.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2004.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 120.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 122.

- ↑ Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 123.

- 1 2 Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 182.

- ↑ Engen, Rodney (1991). Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press. p. 69.

- ↑ Jones, Elwyn (1998). The Alice Companion: A Guide to Lewis Carroll's Alice Books. New York: New York University Press. p. 251.

- 1 2 Morris, Frankie (2005). Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 189.

- ↑ Hancher, Michael (1985). The Tenniel Illustrations to the Alice Books. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. p. 120.

- 1 2 3 Hancher, Michael (1985). The Tenniel Illustrations to the Alice Books. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Hancher, Michael (1985). The Tenniel Illustrations to the Alice Books. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. p. 127.

- ↑ "Name of article??", Daily Graphic, 27 February 1914, p. ?

- ↑ "LondonTown". Tenniel Close. LondonTown. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ↑ From 1854 Tenniel lived not in Bayswater but in Portsdown Road, Maida Vale, a little way to the north."Maida Vale - History". LondonWide. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

Bibliography

- Buchanan-Brown, John. Early Victorian Illustrated Books: Britain, France and Germany. London: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2005.

- Carroll, Lewis. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Edited by Roger Lancelyn Green. Illustrated by John Tenniel. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1971.

- Carroll, Lewis. The Annotated Alice: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Introduction and notes by Martin Gardner. Illustrated by John Tenniel. New York: Bramhall House, 1960.

- Cohen, Morton N. and Edward Wakeling (eds). Lewis Carroll and His Illustrators: Collaborations and Correspondence, 1865–1898. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2003.

- Curtis, L. Perry. Review of book. Sir John Tenniel: Aspects of His Work. Victorian Studies. Vol.40. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1996. 168-71. JSTOR recovered 21 November 2010.

- Curtis, L. Perry. Review of book. Drawing Conclusions: A Cartoon History of Anglo-Irish Relations, 1798-1998 by Roy Douglas, et al. Victorian Studies. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2001. 520-22. JSTOR recovered 21 November 2010.

- Dalziel, Edward D. and George Dalziel. The Brothers Dalziel: A Record of Fifty Years' Work. London: Methuen, 1901.

- Engen, Rodney. Sir John Tenniel: Alice's White Knight. Brookfield, VT: Scolar Press, 1991.

- Garvey, Eleanor M. and W. H. Bond. Introduction. Tenniel's Alice. Cambridge: Harvard College Library-The Stinehour Press, 1978.

- Gladstone, J. Francis, and Elwyn-Jones, Jo. The Alice Companion. Palgrave Macmillan, 1998. ISBN 9780333673492.

- Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustrators. Aldershot, UK: Scolar Press, 1996.

- Hancher, Michael. The Tenniel Illustrations to the Alice Books. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1985.

- Mespoulet, Marguerite. Creators of Wonderland. New York: Arrow Editions, 1934.

- Levin, Harry. Wonderland Revisited. The Kenyon Review. Vol. 27, no. 4. Kenyon College: 1965. 591-616. JSTOR recovered 3 December 2010.

- Morris, Frankie. Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 2005.

- Morris, Frankie. John Tenniel, Cartoonist: A Critical and Sociocultural Study in the Art of the Victorian Political Cartoon. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia: U of Missouri, 1985.

- Monkhouse, William Cosmo. The Life and Works of Sir John Tenniel. London: ArtJournal Easter Annual, 1901.

- Ovenden, Graham and John Davis. The Illustrators of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. New York: St Martin's Press, 1972.

- Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties: An Illustrated Survey of the Work of 58 British Artists. New York: Dover Publications, 1975.

- Sarzano, Frances. Sir John Tenniel. London: Pellegrini & Cudahy, 1948.

- Simpson, Roger. Sir John Tenniel: Aspects of His Work. Rutherford: Associated University Presses, Inc, 1994.

- Stead, William Thomas (ed). The Review of Reviews. Vol. 23, p. 406. London: Horace Marshall & Son, 1901.

- Spielmann, M. H. The History of Punch. London: Cassell, 1895.

- Stoker, G. P. Sir John Tenniel A study of his development as an artist, with particular reference to the Book Illustrations and Political Cartoons, U of London PhD thesis, 1994.

- Susina, Jan. The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children's Literature. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Susina, Jan. Review of book. Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons and Illustrations of Tenniel. Children's Literature Association Quarterly. vol. 31, no. 2, pages 202–205. The Johns Hopkins UP, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Tenniel. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article about John Tenniel. |

- Wakeling, Edward (March 2008). "JOHN TENNIEL (1820-1914)". Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Works by John Tenniel at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Tenniel at Internet Archive

- Tenniel Illustrations for Alice in Wonderland by Sir John Tenniel at Project Gutenberg

- John Tenniel's illustrations for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass

- More about John Tenniel and the making of the illustrations for the Alice's Adventures in Wonderland books

- A collection of Tenniel's American Civil War-era illustrations

"Tenniel, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Tenniel, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.- Works by John Tenniel at HeidICON