Skylab 2

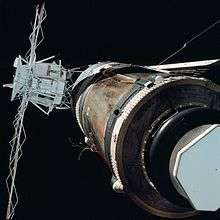

Skylab, seen from the departing Skylab 2 spacecraft | |||||

| Operator | NASA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1973-032A | ||||

| SATCAT № | 6655 | ||||

| Mission duration | 28 days, 49 minutes, 49 seconds | ||||

| Distance travelled | 18,500,000 kilometers (10,000,000 nautical miles) | ||||

| Orbits completed | 404 | ||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||

| Spacecraft | Apollo CSM-116 | ||||

| Manufacturer | North American Rockwell | ||||

| Launch mass | 19,979 kilograms (44,046 lb) | ||||

| Crew | |||||

| Crew size | 3 | ||||

| Members | |||||

| Start of mission | |||||

| Launch date | May 25, 1973, 13:00:00 UTC | ||||

| Rocket | Saturn IB SA-206 | ||||

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B | ||||

| End of mission | |||||

| Recovered by | USS Ticonderoga | ||||

| Landing date | June 22, 1973, 13:49:48 UTC | ||||

| Landing site | 24°45′N 127°2′W / 24.750°N 127.033°W | ||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||

| Reference system | Geocentric | ||||

| Regime | Low Earth | ||||

| Perigee | 428 kilometers (231 nautical miles) | ||||

| Apogee | 438 kilometers (237 nautical miles) | ||||

| Inclination | 50.0 degrees | ||||

| Period | 93.2 minutes | ||||

| Epoch | June 4, 1973[1] | ||||

| Docking with Skylab | |||||

| Docking port | Forward | ||||

| Docking date | May 26, 1973, 09:56 UTC | ||||

| Undocking date | May 26, 1973, 10:45 UTC | ||||

| Time docked | 49 minutes[2] | ||||

| Docking with Skylab | |||||

| Docking port | Forward | ||||

| Docking date | May 26, 1973, 15:50 UTC[2] | ||||

| Undocking date | June 22, 1973, 08:58 UTC[3] | ||||

| Time docked | 26 days, 11 hours, 2 minutes | ||||

Due to a NASA management error, manned Skylab mission patches were designed in conflict with the official mission numbering scheme.  L-R: Kerwin, Conrad, and Weitz

| |||||

Skylab 2 (also SL-2 and SLM-1[4]) was the first manned mission to Skylab, the first U.S. orbital space station. The mission was launched on a Saturn IB rocket and carried a three-person crew to the station. The name Skylab 2 also refers to the vehicle used for that mission. The Skylab 2 mission established a twenty-eight-day record for human spaceflight duration. Furthermore, its crew were the first space station occupants ever to return safely to Earth – the only previous space station occupants, the crew of the 1971 Soyuz 11 mission that had manned the Salyut 1 station for twenty-four days, were killed during reentry.

The manned Skylab missions were officially designated Skylab 2, 3, and 4. Miscommunication about the numbering resulted in the mission emblems reading Skylab I, Skylab II, and Skylab 3 respectively.[4][5]

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr. Fourth and last spaceflight | |

| Science Pilot | Joseph P. Kerwin Only spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Paul J. Weitz First spaceflight | |

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Russell L. Schweickart | |

| Science Pilot | F. Story Musgrave | |

| Pilot | Bruce McCandless, II | |

Support crew

Mission parameters

- Mass: 19,979 kg

- Maximum Altitude: 440 km

- Distance: 18,536,730.9 km

- Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB

- Perigee: 428 km

- Apogee: 438 km

- Inclination: 50°

- Period: 93.2 min

- Soft Dock: May 26, 1973 – 09:56 UTC

- Undocked: May 26, 1973 – 10:45 UTC

- Time Docked: 49 minutes

- Hard Dock: May 26, 1973 – 15:50 UTC

- Undocked: June 22, 1973 – 08:58 UTC

- Time Docked: 26 days, 11 hours, 2 minutes

Space walks

- Weitz — EVA 1 (stand up EVA — CM side hatch)

- Start: May 26, 1973, 00:40 UTC

- End: May 26, 01:20 UTC

- Duration: 40 minutes

- Conrad and Kerwin — EVA 2

- Start: June 7, 1973, 15:15 UTC

- End: June 7, 18:40 UTC

- Duration: 3 hours, 25 minutes

- Conrad and Weitz — EVA 3

- Start: June 19, 1973, 10:55 UTC

- End: June 19, 12:31 UTC

- Duration: 1 hour, 36 minutes

Mission highlights

The Skylab station suffered significant damage on its May 14 launch: its micrometeorite shield, and one of its primary solar arrays had torn loose during launch, and the remaining primary solar array was jammed. Without the shield which was designed to also provide thermal protection, Skylab baked in the Sun, and rising temperatures inside the workshop released toxic materials into the station's atmosphere and endangered on-board film and food. The first crew was supposed to launch on May 15, but instead had to train practicing repair techniques as they were developed by the engineers.[6]:253–255,259 Ground controllers purged the atmosphere with pure nitrogen four times, before refilling it with the nitrogen/oxygen atmosphere for the crew.[7]

On May 25, Skylab 2 lifted from LC-39B, the first Saturn IB launch in almost five years and only the second-ever launch from Pad 39B. Booster performance was nominal except for one momentary glitch that could have threatened the mission - when the Commit signal was sent to the Saturn at ignition, the instrument unit sent a command to switch the launch vehicle from internal to external power. This would have shut down the Saturn's electrical system, but not the propulsion system and likely cause the disaster scenario of an uncontrollable booster, requiring the Launch Escape System to be activated and the Command Module pulled away to safety, followed by Range Safety destroying the errant launch vehicle. However, the duration of the cutoff signal was less than one second, too short of a time for the electrical relay in the booster to be activated, thus nothing happened and the launch proceeded as planned. This glitch was traced to a modification of the pad electrical equipment and corrective steps were subsequently taken to prevent it from happening again.[6]:269[8] On reaching the station, Conrad flew their Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM) around it to inspect the damage, then soft-docked with it to avoid the necessity of station keeping while the crew ate, and flight controllers planned the first repair attempt. Then they undocked so that Conrad could position the Apollo by the jammed solar panel, so that Weitz could perform a stand-up EVA, trying to free the array by tugging at it with a 10-foot hooked pole, while Kerwin held onto his legs. This failed, and consumed a significant amount of the Skylab's nitrogen maneuvering fuel to keep it steady in the process.

The crew then attempted to perform the hard dock to Skylab, but the capture latches failed to operate. After eight failed attempts, they donned their pressure suits again and partially dis-assembled the CSM's docking probe; the next attempt worked. Once inside the station, the crew deployed a collapsible parasol through the small scientific airlock to act as a sunshade. (This approach was suggested and designed by NASA's "Mr. Fix It" Jack Kinzler, who was awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal for the effort.) Successful deployment of the sunshade dropped inside temperatures to sustainable levels.[9]

Two weeks later, Conrad and Kerwin performed a second EVA, finally freeing the stuck solar panel and increasing the electrical power to the workshop. They had prepared for this repair by practicing in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at the Marshall Space Flight Center. Without power from the panel, the second and third Skylab missions would have been unable to perform their main experiments, and the station's critical battery system would have been seriously degraded.[6]:271–276 During this EVA, the sudden deployment of the solar panel structure caused both astronauts to be flung from the Skylab hull, testing their nerves as well as the strength of their safety tethers. After recovering their composure, both astronauts returned to their positions on Skylab and completed the EVA.[10]

For nearly a month they made further repairs to the workshop, conducted medical experiments, gathered solar and Earth science data, and performed a total of 392 hours of experiments. The mission tracked two minutes of a large solar flare with the Apollo Telescope Mount; they took and returned some 29,000 frames of film of the sun.[6]:291 The Skylab 2 astronauts spent 28 days in space, which doubled the previous U.S. record. The mission ended successfully on June 22, 1973, when Skylab 2 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 9.6 km from the recovery ship USS Ticonderoga. Skylab 2 set the records for the longest duration manned spaceflight, greatest distance traveled and greatest mass docked in space. Conrad set the record for most time in space for an astronaut.

Mission insignia

The Skylab 1 patch was designed by Kelly Freas, a well-known artist highly regarded in the science fiction community, who was suggested to NASA by science fiction author and editor Ben Bova. The insignia features Skylab above the earth with the sun in the background. In an article for Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact magazine, Freas said, "Among the suggestions the astronauts had made was the idea of a solar eclipse as seen from Skylab. It soon became clear that this idea would solve several problems at once: it pointed up the solar study function of Skylab, it would give me the large circular shape of the Earth as counterpoint to the angularity of the cluster, and it would establish firmly the connection of Skylab to the Earth. In addition, it would give a chance to get the necessary high contrast for good visibility of the tiny finished patch. ... I made several studies of cloud patterns on the planet, reducing them finally to very conventionalized swirls. The Skylab cluster was simplified and simplified again, till it became simply a black form with a white edgelight to set it off."

Gallery

Kerwin blows water droplets from a straw

Kerwin blows water droplets from a straw Weitz assists Kerwin with a blood pressure cuff

Weitz assists Kerwin with a blood pressure cuff

Spacecraft location

The command module they flew to the station in is displayed at the National Museum of Naval Aviation, Pensacola, Florida.

Skylab 2 CM

Skylab 2 CM Skylab 2 CM

Skylab 2 CM Skylab 2 CM interior

Skylab 2 CM interior

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skylab 2. |

References

- ↑ McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Skylab: A Chronology, May 26, 1973

- ↑ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft (Second ed.). New York: MacMillan. p. 223. ISBN 0-02-542820-9.

- 1 2 "Skylab Numbering Fiasco". Living in Space. William Pogue Official WebSite. 2007. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ↑ Pogue, William. "Naming Spacecraft: Confusion Reigns". collectSPACE. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Benson, Charles Dunlap and William David Compton. Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab. NASA publication SP-4208.

- ↑ Skylab: A Chronology, May 14

- ↑ http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19730025087.pdf

- ↑ "SP-400 Skylab, Our First Space Station". NASA. 1977. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ David J. Shayler, FBIS, Walking in Space, 2004, p. 213, Praxis Publishing Ltd.

- Skylab: Command service module systems handbook, CSM 116 – 119 (PDF) April 1972

- Skylab Saturn 1B flight manual (PDF) September 1972

- NASA Skylab Chronology

- Marshall Space Flight Center Skylab Summary

- Skylab 2 Characteristics SP-4012 NASA HISTORICAL DATA BOOK

- Analog interview with Frank Kelly Freas

Multimedia

![]() Media related to Skylab 2 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Skylab 2 at Wikimedia Commons