Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

| Slovak Republic | ||||||||||

| Slovenská republika | ||||||||||

| Client state of Nazi Germany | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Motto Verní sebe, svorne napred! "Faithful to Ourselves, Together Ahead!" | ||||||||||

| Anthem Hej, Slováci English: "Hey, Slovaks" | ||||||||||

.svg.png) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Bratislava | |||||||||

| Languages | Slovak, Hungarian | |||||||||

| Religion | Christianity[1] | |||||||||

| Government | Clerico-fascist one-party state | |||||||||

| President | ||||||||||

| • | 1939–1945 | Jozef Tiso | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||

| • | 1939 | Jozef Tiso | ||||||||

| • | 1939–1944 | Vojtech Tuka | ||||||||

| • | 1944–1945 | Štefan Tiso | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | |||||||||

| • | Indep. declared | 14 March 1939 | ||||||||

| • | Slovak–Hun. War | 23 March 1939 | ||||||||

| • | Constitution adopted | 21 July 1939 | ||||||||

| • | Invasion of Poland | 1 September 1939 | ||||||||

| • | National Uprising | 29 August 1944 | ||||||||

| • | Fall of Bratislava | 4 April 1945 | ||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||

| • | 1940 | 38,055 km² (14,693 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||

| • | 1940 est. | 2,653,053 | ||||||||

| Density | 69.7 /km² (180.6 /sq mi) | |||||||||

| Currency | Slovak koruna | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The (First) Slovak Republic (Slovak: [prvá] Slovenská republika) otherwise known as the Slovak State (Slovak: Slovenský štát) was a client state of Nazi Germany which existed between 14 March 1939 and 4 April 1945. It controlled the majority of the territory of present-day Slovakia, but without its current southern and eastern parts, which had been ceded to Hungary in 1938. The Republic bordered Germany, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Poland – and subsequently the General Government (German-occupied remnant of Poland) – and Hungary.

Germany recognized the Slovak State, as did several other states, including the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, Croatia, El Salvador, Estonia, Italy, Hungary, Japan, Lithuania, Manchukuo, Mengjiang, Romania, the Soviet Union, Spain, Switzerland, and the Vatican City. The majority of the Allies of World War II never recognized the existence of Slovak state. The only exception was Soviet Union who nullified its recognition after Slovakia joined the invasion in 1941.

Name

The official name of the country was the Slovak State (Slovak: Slovenský štát) from 14 March to 21 July 1939 (until the adoption of the Constitution), and the Slovak Republic (Slovak: Slovenská republika) from 21 July 1939 to its end in April 1945. The country is often referred to historically as the First Slovak Republic (Slovak: prvá Slovenská republika) to distinguish it from the contemporary (Second) Slovak Republic, Slovakia, which is not considered its legal successor state. The name "Slovak State" was used colloquially, but the term "First Slovak Republic" was used even in encyclopaedias written during Communist rule.[2][3]

Creation

After the Munich Agreement, Slovakia gained autonomy inside Czecho-Slovakia (as the former Czechoslovakia had been renamed) and lost its southern territories to Hungary under the First Vienna Award. As the Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler was preparing a mobilisation into Czech territory and creation of his Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, he had various plans for Slovakia. German officials were initially misinformed by the Hungarians that the Slovaks wanted to join Hungary. Germany decided to make Slovakia a separate puppet state under the influence of Germany, and a potential strategic base for German attacks on Poland and other regions.

.jpg)

On 13 March 1939, Hitler invited Monsignor Jozef Tiso, (the Slovak ex-prime minister who had been deposed by Czechoslovak troops several days earlier), to Berlin and urged him to proclaim Slovakia's independence. Hitler added that, if Tiso did not consent, he would have no interest in Slovakia's fate and would leave it to the territorial claims of Hungary and Poland. During the meeting, Joachim von Ribbentrop passed on a report claiming that Hungarian troops were approaching the Slovak borders. Tiso refused to make such a decision himself, after which he was allowed by Hitler to organise a meeting of the Slovak parliament ("Diet of the Slovak Land") which would approve Slovakia's independence.

On 14 March, the Slovak parliament convened and heard Tiso's report on his discussion with Hitler as well as on a possible declaration of independence. Some of the deputies were skeptical of making such a move, among other reasons due to the fact that some worried that the Slovak state would be too small and with a strong Hungarian minority.[4] The debate was quickly brought to a head when Franz Karmasin, leader of the German minority in Slovakia, said that any delay in declaring independence would result in Slovakia being divided between Hungary and Germany. Under these circumstances, Parliament unanimously declared Slovak independence, thus creating the first Slovak state in history.[4] Jozef Tiso was appointed the first Prime Minister of the new republic. The next day, Tiso sent a telegram (which had actually been composed the previous day in Berlin) asking the Reich to take over the protection of the newly minted state. The request was readily accepted.[5]

Slovak military

War with Hungary

On 23 March 1939, Hungary, having already occupied Carpatho-Ukraine, attacked from there, and the newly established Slovak Republic was forced to cede 1,697 km² of territory with about 70,000 people to Hungary before the onset of World War II.

Slovak forces during the campaign against Poland (1939)

Slovakia was the only Axis nation other than Germany to take part in the Polish Campaign. With the impending German invasion of Poland planned for September 1939, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) requested the assistance of Slovakia. Although the Slovak military was only six months old, it formed a small mobile combat group consisting of a number of infantry and artillery battalions. Two combat groups were created for the campaign in Poland for use alongside the Germans. The first group was a brigade-sized formation that consisted of six infantry battalions, two artillery battalions, and a company of combat engineers, all commanded by Antonín Pulanich. The second group was a mobile formation that consisted of two battalions of combined cavalry and motorcycle recon troops along with nine motorised artillery batteries, all commanded by Gustav Malár. The two groups were organized around the headquarters of the 1st and 3rd Slovak Infantry Divisions. The two combat groups fought while pushing through the Nowy Sącz and Dukla Mountain Passes, advancing towards Dębica and Tarnów in the region of southern Poland.

Slovak forces during the campaign against the Soviet Union

The Slovak military participated in the war on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union. The Slovak Expeditionary Army Group of about 45,000 entered the Soviet Union shortly after the German attack. This army lacked logistic and transportation support, so a much smaller unit, the Slovak Mobile Command (Pilfousek Brigade), was formed from units selected from this force; the rest of the Slovak army was relegated to rear-area security duty. The Slovak Mobile Command was attached to the German 17th Army (as was the Hungarian Carpathian Group also) and shortly thereafter given over to direct German command, the Slovaks lacking the command infrastructure to exercise effective operational control. This unit fought with the 17th Army through July 1941, including at the Battle of Uman.[6]

At the beginning of August 1941, the Slovak Mobile Command was dissolved and instead two infantry divisions were formed from the Slovak Expeditionary Army Group. The Slovak 2nd Division was a security division, but the Slovak 1st Division was a front-line unit which fought in the campaigns of 1941 and 1942, reaching the Caucasus area with Army Group B. The Slovak 1st Division then shared the fate of the German southern forces, losing their heavy equipment in the Kuban bridgehead, then being badly mangled near Melitopol in the southern Ukraine. In June 1944 the remnant of the division, no longer considered fit for combat due to low morale, was disarmed and the personnel assigned to construction work, a fate which had already befallen the Slovak 2nd Division earlier for the same reason.[6]

Slovak National Uprising

In the 1944 Slovak National Uprising, many Slovak units sided with the Slovak resistance and rebelled against Tiso's collaborationist government, while others helped German forces put the uprising down.

International relations

From the beginning, the Slovak Republic was under the influence of Germany. The so-called "protection treaty" (Treaty on the protective relationship between Germany and the Slovak State), signed on 23 March 1939, partially subordinated its foreign, military, and economic policy to that of Germany. The German Wehrmacht established the so-called "protection zone" in Western Slovakia in August 1939. The Slovak-Soviet Treaty of Commerce and Navigation was signed at Moscow on 6 December 1940.[7]

The most difficult foreign policy problem of the state were the relations with Hungary, which had annexed one third of Slovakia's territory by the First Vienna Award, Slovakia tried to achieve a revision of the Vienna Award, but Germany did not allow it. There were also constant quarrels concerning Hungary's treatment of Slovaks living in Hungary.

Characteristics

85% of the inhabitants of the Slovak Republic were Slovaks, the remaining 15% were made up of Germans, Hungarians, Jews and Romani. 50% of the population were employed in agriculture. The state was divided in six counties (župy), 58 districts (okresy) and 2659 municipalities. The capital Bratislava had over 140,000 inhabitants.

The state continued the legal system of Czechoslovakia, which was modified only gradually. According to the Constitution of 1939, the "President" (Jozef Tiso) was the head of the state, the "Assembly/Diet of the Slovak Republic" elected for five years was the highest legislative body (no general elections took place, however), and the "State Council" performed the duties of a senate. The government with eight ministries was the executive body.

The Slovak Republic was an authoritarian state where the German pressure resulted in the adoption of many elements of German Nazism. Some historians characterized the Slovak regime from 1939 to 1945 as clerical fascism. The government issued a number of antisemitic laws, prohibiting the Jews from participation in public life, and later supported their deportation to concentration camps erected by Germany on Polish territory. The only political parties permitted were the dominant Hlinka's Slovak People's Party and two smaller openly fascist parties, these being the Hungarian National Party which represented the Hungarian minority and the German Party which represented the German minority.

On the other hand, the existence of the Slovak Republic had some noticeable positive effects for the country's economy, science, education and culture. The Slovak Academy of Sciences was founded in 1942, a number of new universities and high schools were established, and Slovak literature and culture flourished.

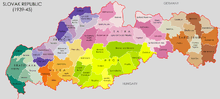

Administrative divisions

The Slovak Republic was divided into 6 counties and 58 districts as of 1 January 1940. The extant population records are from the same time:

- Bratislava county (Bratislavská župa), 3,667 km², with 455,728 inhabitants, and 6 districts: Bratislava, Malacky, Modra, Senica, Skalica, and Trnava.

- Nitra county (Nitrianska župa), 3,546 km², with 335,343 inhabitants, and 5 districts: Hlohovec, Nitra, Prievidza, Topoľčany, and Zlaté Moravce.

- Trenčín county (Trenčianska župa), 5,592 km², with 516,698 inhabitants, and 12 districts: Bánovce nad Bebravou, Čadca, Ilava, Kysucké Nové Mesto, Myjava, Nové Mesto nad Váhom, Piešťany, Považská Bystrica, Púchov, Trenčín, Veľká Bytča, and Žilina.

- Tatra county (Tatranská župa), 9,222 km², with 463,286 inhabitants, and 13 districts: Dolný Kubín, Gelnica, Kežmarok, Levoča, Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš, Námestovo, Poprad, Ružomberok, Spišská Nová Ves, Spišská Stará Ves, Stará Ľubovňa, Trstená, and Turčiansky Svätý Martin.

- Šariš-Zemplín county (Šarišsko-zemplínska župa), 7,390 km², with 440,372 inhabitants, and 10 districts: Bardejov, Giraltovce, Humenné, Medzilaborce, Michalovce, Prešov, Sabinov, Stropkov, Trebišov, and Vranov nad Topľou.

- Hron county (Pohronská župa), 8,587 km², with 443,626 inhabitants, and 12 districts: Banská Bystrica, Banská Štiavnica, Brezno nad Hronom, Dobšiná, Hnúšťa, Kremnica, Krupina, Lovinobaňa, Modrý Kameň, Nová Baňa, Revúca, and Zvolen.

The Holocaust

Soon after independence and along with mass exile and deportation of Czechs, the Slovak Republic began a series of measures aimed against the Jews in the country. The Hlinka's Guard began to attack Jews, and the "Jewish Code" was passed in September 1941. Resembling the Nuremberg Laws, the code required that Jews wear a yellow armband, and were banned from intermarriage and many jobs. By October 1941, 15,000 Jews were expelled from Bratislava; many were sent to labour camps.

The Slovak Republic was one of the countries to agree to deport its Jews as part of the Nazi Final Solution. Originally, the Slovak government tried to make a deal with Germany in October 1941 to deport its Jews as a substitute for providing Slovak workers to help the war effort. After the Wannsee Conference, the Germans agreed to the Slovak proposal, and a deal was reached where the Slovak Republic would pay for each Jew deported, and, in return, Germany promised that the Jews would never return to the republic. The initial terms were for "20,000 young, strong Jews", but the Slovak government quickly agreed to a German proposal to deport the entire population for "evacuation to territories in the East" meaning to Auschwitz-Birkenau.[8]

The deportations of Jews from Slovakia started on 25 March 1942, but halted on 20 October 1942 after a group of Jewish citizens, led by Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Ber Weissmandl, built a coalition of concerned officials from the Vatican and the government, and, through a mix of bribery and negotiation, was able to stop the process. By then, however, some 58,000 Jews had already been deported, mostly to Auschwitz. Slovak government officials filed complaints against Germany, when it became clear that many of the previously deported Slovak Jews had been gassed in mass executions.[8]

Jewish deportations resumed on 30 September 1944, when the Soviet army reached the Slovak border, and the Slovak National Uprising took place. As a result of these events, Germany decided to occupy all of Slovakia and the country lost its independence. During the German occupation, another 13,500 Jews were deported and 5,000 were imprisoned. Deportations continued until 31 March 1945. In all, German and Slovak authorities deported about 70,000 Jews from Slovakia; about 65,000 of them were murdered or died in concentration camps. The overall figures are inexact, partly because many Jews did not identify themselves, but one 2006 estimate is that approximately 105,000 Slovak Jews, or 77% of their pre-war population, died during the war.[9]

SS plans for Slovakia

Although the official policy of the Nazi regime was in favour of an independent Slovak state dependent on Germany and was opposed to any annexations of Slovak territory, Heinrich Himmler's SS considered ambitious population policy options concerning the German minority of Slovakia, which numbered circa 130,000 people.[10] In 1940, Günther Pancke, head of the SS RuSHA ("Race and Settlement Office") undertook a study trip in Slovak lands where ethnic Germans were present, and reported to Himmler that the Slovak Germans were in danger of disappearing.[10] Pancke recommended that action should be taken to fuse the racially valuable part of the Slovaks into the German minority and remove the Gypsy and Jewish populations.[10] He stated that this would be possible by "excluding" the Hungarian minority of the country, and by settling some 100,000 ethnic German families to Slovakia.[10] The racial core of this Germanization policy was to be gained from the Hlinka Guard, which was to be further integrated into the SS in the near future.[10]

Leaders and politicians

President

- Jozef Tiso (14 March 1939 - 3 April 1945)

Prime Ministers

- Jozef Tiso (14 March 1939 – 29 October 1939)

- Vojtech "Béla" Tuka (29 October 1939 – 5 September 1944)

- Štefan Tiso (5 September 1944 – 3 April 1945)

Commanders of German occupation forces

- Ogruf. Gottlob Christian Berger (29 August 1944 – 20 September 1944)

- Ogruf. Hermann Höfle (20 September 1944 – 3 April 1945)

Commanders of Soviet occupation forces

- G.A. Ivan Yefimovich Petrov (6 August 1944 – 24 March 1945)

- G.A. Andrey Ivanovich Yeryomenko (25 April 1945 – July 1945)

End of the Slovak Republic

After the anti-Nazi Slovak National Uprising in August 1944, the Germans occupied the country (from September 1944), which thereby lost much of its independence. The German troops were gradually pushed out by the Red Army, by Romanian and by Czechoslovak troops coming from the east. The liberated territories became de facto part of Czechoslovakia again.

The First Slovak Republic ceased to exist de facto on 4 April 1945 when the Red Army captured Bratislava and occupied all of Slovakia. De jure it ceased to exist when the exiled Slovak government capitulated to General Walton Walker leading the XX Corps of the 3rd US Army on 8 May 1945 in the Austrian town of Kremsmünster. In summer 1945, the captured former president and members of former government were handed over to Czechoslovak authorities.

Several prominent Slovak politicians escaped to neutral countries. Following his captivity, the deposed president Jozef Tiso authorized the former foreign minister Ferdinand Ďurčanský as his successor. Ďurčanský, Tiso's personal secretary Karol Murín, and cousin Fraňo Tiso were appointed by ex-president Tiso as the representatives of the Slovak nation, however they failed to create a government-in-exile as no country recognized them. In the 1950s with fellow Slovak nationalist they established Slovak Action Committee (later Slovak Liberation Committee) which unsuccessfully advocated the restoration of the independent Slovak State and the renewal of war against the Soviet Union. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia and the creation of the Slovak republic, the Slovak Liberation Committee proclaimed Tiso's authorization as obsolete.

See also

- History of Slovakia

- History of Czechoslovakia

- History of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Slovak Soviet Republic (1919)

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945)

- Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (1939–1945)

- Military history of Carpathian Ruthenia during World War II

- Slovenské vzdušné zbrane – World War II Slovak Air Force

- History of Czechoslovakia (1945–1948)

- History of Czechoslovakia (1948–1989)

- Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1960–1989)

- Slovak Socialist Republic (1969–1990)

- History of Czechoslovakia (1989–1992)

- Czech Republic (1993–present)

- Slovakia (1993–present)

References

- ↑ Law and Religion in Europe: A Comparative Introduction

- ↑ Vladár, J. (Ed.), Encyklopédia Slovenska V. zväzok R – Š. Bratislava, Veda, 1981, pp. 330–331

- ↑ Plevza, V. (Ed.) Dejiny Slovenského národného povstania 1944 5. zväzok. Bratislava, Nakladateľstvo Pravda, 1985, pp. 484–487

- 1 2 Dominik Jůn interviewing Professor Jan Rychlík (2016). "Czechs and Slovaks - more than just neighbours". Radio Prague. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- 1 2 Jason Pipes. "Slovakian Axis Forces in WWII". Feldgrau. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ National Archives, document reference FO 371/24856

- 1 2 Branik Ceslav & Carmelo Lisciotto, H.E.A.R.T (2008). "The Fate of the Slovak Jews". Holocaust Research Project.org. Sources: G. Reitlinger, Avigdor Dagan, Raul Hilberg, Israel Gutman, Yitzhak Arad, OMDA Archives. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Rebekah Klein-Pejšová (2006). "An overview of the history of Jews in Slovakia". Slovak Jewish Heritage. Synagoga Slovaca. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Longerich, P. (2008), Heinrich Himmler, p. 458, ISBN 0-19-161989-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Slovak Republic. |

- Axis History Factbook — Slovakia

- Selected laws of the First Slovak Republic, including the constitution (in Slovak)

- Map

- A Comparison of the First and Second Slovak Republics’ Political Systems

Coordinates: 48°08′N 17°06′E / 48.133°N 17.100°E

.svg.png)