Battle of Annual

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Annual was fought on July 22, 1921, at Annual in Spanish Morocco, between the Spanish Army of Africa and Berber combatants of the Rif region during the Rif War. The Spanish suffered a major military defeat, almost always referred to by the Spanish as the Disaster of Annual, which led to major political crises and a redefinition of Spanish colonial policy toward the Rif.

Description

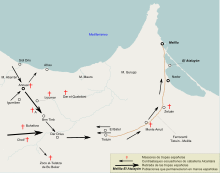

In early 1921 the Spanish Army commenced an offensive into northeastern Morocco from the coastal regions they already held. The advance took place without extended lines of communication being adequately established or the complete subjugation of the areas occupied. In the course of the Spanish offensive, general Silvestre had penetrated almost 130 kilometres into the enemy lines but during the hasty advances neither reliable forts nor water supplies points had been put in place, only multiple small makeshift garrisons known as blocaos, manned by a handful of soldiers (typically 12-20) greatly spread out in high places without own water sources nor good communication with the main positions[7]

On July 22, 1921, after five days of siege, 5,000 Spanish forces under the command of general Manuel Fernández Silvestre garrisoning the encampment of Annual[7] were attacked and destroyed by 3,000 Riffi, with the withdrawal ordered by General Silvestre ending up in a disorganized rout.[7]

The riffi irregular forces were commanded by Muhammad Ibn 'Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi (usually known as Abd el Krim), a former civil servant at the Spanish administration in the Office of Indigenous Affairs in Melilla and one of the leaders of the tribe of the Aith Ouriaghel.

The overextended Spanish military structure in the Western Spanish Protectorate in Morocco crumbled. After the battle, the Riffian Berbers began to advance eastward, where they overran more than 130 Spanish blocaos.[8] The Spanish garrisons were destroyed without mounting a coordinated response to the attacks. At the end of August 1921, Spain had lost all the territories it had gained in the area since 1909.[8] General Silvestre disappeared and his remains were never found.[9] One version claims that Spanish Sergeant Francisco Basallo Berrcerra of the Kandussi garrison, who survived the Dar Quebdani massacre –where 900 Spanish soldiers were killed in cold blood after surrendering–[10] identified the remains of Silvestre by his general's sash. A Moorish courier from Kaddur Namar claimed that, eight days after the battle, he saw the corpse of the general lying face down on the battlefield.[11]

Spanish retreats

At Afrau, on the coast, Spanish warships were able to evacuate the garrison. At Zoco el Telata de Metalsa in the south, Spanish troops and civilians were able to retreat to the French Zone. Spanish survivors of the battle retreated some 80 km to the encampment of Monte Arruit, where a stand was attempted under the command of General Felipe Navarro y Ceballos-Escalera. As this position was surrounded and cut off from supplies, General Dámaso Berenguer Fusté, Spanish High Commissioner in the protectorate, authorized surrender on August 9. The Rifeños reportedly did not respect the conditions of surrender and killed 3,000 Spanish soldiers.[12] General Navarro was taken prisoner, along with 534 military personnel and 53 civilians[13] who were ransomed some years later.[12]

Melilla was only some 40 km away, but was in no position to help: the city was almost defenceless and lacked properly trained troops. The Spanish quickly reinforced Melilla with 14,000 men from the Spanish Legion and other units.[14] Abdelkrim did not have enough men to lay siege to the city, and he decided not to attack; citizens of western European nations were living in Melilla, and he did not wish to risk international disapproval.[14] He later stated that this was his biggest mistake.[15]

Spain quickly assembled elite units of the Army of Africa which had been operating south of Tetuan in the Western Zone. These mainly comprised Spanish Legion and Moroccan Regulares newly recruited in 1920. Transferred to Melilla by sea, these reinforcements enabled the city to be held and Monte Arruit to be retaken by the end of November.

The Spaniards may have lost more than 20,000 soldiers at Annual.[5] German historian Werner Brockdorff states that only 1,200 of the 20,000 Spanish troops escaped alive, [3] though the estimated losses may be exaggerated. Rif casualties were 800.[4] Final official figures for the Spanish death toll, both at Annual and during the subsequent rout which took Riffian forces to the outskirts of Melilla, were reported to the Cortes Generales as totaling 13,192 killed.[16]

Materiel lost by the Spanish, in the summer of 1921 and especially in the Battle of Annual, included 11,000 rifles, 3,000 carbines, 1,000 muskets, 60 machine guns, 2,000 horses, 1,500 mules, 100 cannon, and a large quantity of ammunition.[17] Abd el Krim remarked later: "In just one night, Spain supplied us with all the equipment which we needed to carry on a big war."[17] Other sources give the amount of booty seized by Rif warriors as 20,000 rifles (German made Mausers), 400 machine guns (Hotchkisses), and 120–150 artillery pieces (Schneiders).[18][19][20]

Aftermath

The political crisis brought about by this disaster led Indalecio Prieto to say in the Congress of Deputies: "We are at the most acute period of Spanish decadence. The campaign in Africa is a total, absolute failure of the Spanish Army, without extenuation." The Minister of War ordered the creation of an investigative commission, led by General Juan Picasso González, which developed the report known as Expediente Picasso. The report detailed numerous military mistakes, but owing to the obstructive action of various ministers and judges, did not go so far as to lay political responsibility for the defeat. In all, the defeat is often thought of in Spain as the worst of the Spanish army in modern times.[21]

The reasons for the crushing defeat may lie with Silvestre's tactical decisions and the fact that the bulk of the Spanish army was formed by poorly trained conscripts.[12] Popular opinion widely placed the blame for the disaster upon King Alfonso XIII, who according to several sources had encouraged Silvestre's irresponsible penetration to positions far from Melilla without having adequate defenses in his rear. Alfonso's apparent indifference – vacationing in southern France, he reportedly said "Chicken meat is cheap" when informed of the disaster[22] even though other sources render the quote as "chicken meat is expensive" when informed about the ransom demanded by Abd-el-Krim for the officials made prisoners in Mount Arruit–[12] led to a popular backlash against the monarchy. The crisis was one of the many that, over the course of the next decade, undermined the Spanish monarchy and led to the rise of the Second Spanish Republic.

See also

- The Battle of El Herri, a similar battle during the Zaian War in which a French colonial force was defeated by Moroccan irregulars

References

- ↑ Donald Bloxham, A. Dirk Moses : The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies , Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 0191613614, page xxii (part 4 chapter 18)

- ↑ M S Gill: Immortal Heroes Of The World, Sarup & Sons, 2005, ISBN 8176255904, page 242.

- 1 2 Werner Brockdorff: Geheimkommandos des Zweiten Weltkrieges, Verlag Welsermühl, 1967, page 168.

- 1 2 Johannes Ebert, Knut Görich, Detlef Wienecke-Janz: Die große Chronik Weltgeschichte – Band 15 Der erste Weltkrieg und seine Folgen, wissenmedia Verlag, 2008, ISBN 3577090758, page 203. (German)

- 1 2 Long, David E.; Bernard Reich (2002). The Government and Politics of the Middle East and North Africa. p. 393.

- ↑ Martha Eulalia Altisent: A Companion to the Twentieth-Century Spanish Novel, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2008, ISBN 1855661748, page 259.

- 1 2 3 ABC (Spain)(Spanish)

- 1 2 Sasse, 2006, page 40.

- ↑ David S. Woolman, page 91 "Rebels in the Rif", Stanford University Press

- ↑ Annual: horror, masacre y olvido|El País

- ↑ Juan Pando, Historia Secreta del Annual (Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy, 1999), 335–36.

- 1 2 3 4 Vozpopuli.com, accessed August 8, 2016

- ↑ Juan Pando, Historia Secreta del Annual (Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy, 1999), 335.

- 1 2 Sasse, 2006, page 41.

- ↑ J.Roger-Mathieu, Memoires d'Abd-el-Krim (Paris, 1927)

- ↑ David S. Woolman, page 96 "Rebels in the Rif", Stanford University Press

- 1 2 Dirk Sasse, Franzosen, Briten und Deutsche im Rifkrieg 1921–1926, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-486-57983-5, page 157. (German)

- ↑ Margaret Peil, Olatunji Y. Oyeneye: Consensus, Conflict, and Change: A Sociological Introduction to African Societies, East African Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9966467475, page 54.

- ↑ Martin Windrow: French Foreign Legion 1914–45, Osprey Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1855327619, page 14.

- ↑ Jean-Denis G. G. Lepage: The French Foreign Legion: An Illustrated History, McFarland, 2008, ISBN 9780786432394, page 125.

- ↑ La derrota más amarga del Ejército español - ABC.es (Spanish)

- ↑ Woolman, 102

Further reading

- Woolman, David S. Rebels in the Rif – Abd El Krim and the Rif Rebellion. Stanford University Press, 1968.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Annual. |

- The Disaster of Annual (in Spanish).

- "La Guardia Civil en el Desastre de Annual", an article on this topic from the official site of the Spanish Guardia Civil (in Spanish).

- Rif War of 1919–1926 on OnWar.com

- Next publication of Abd el-Krim`s biography on the basis of official Spanish documents

Coordinates: 35°07′12″N 3°34′59″W / 35.120°N 3.583°W