St Andrew's Church, Brighton

| St Andrew's Church, Brighton | |

|---|---|

| Parish Church of Saint Andrew, Brighton, Melbourne | |

|

| |

| Location | Brighton, Melbourne |

| Country | Australia |

| Denomination | Anglican Church |

| Website | standrewsbrighton.org.au |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Louis Williams and Charles Webb |

| Style | Early English Gothic and Modern Gothic |

| Years built | 1857, 1961-1962 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Melbourne |

| Province | Victoria |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Jan Joustra |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Thomas Heywood |

St Andrew's Church, Brighton, is the Anglican parish church of the beachside suburb of Brighton, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Founded in 1842, St Andrew's was one of the earliest Christian churches established in the Port Phillip District and predates both the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne and the colony, now state, of Victoria. Located in a large historic precinct in Middle Brighton, including a rare pre-gold rush graveyard, St Andrew's is one of Australia's most notable churches, known for its liturgical and musical tradition since the mid 19th century.

The present building, opened in 1962, was designed by the noted Australian architect Louis Williams to become the cathedral for the proposed Diocese of the Mornington Peninsula following the planned division of the Diocese of Melbourne.[1] Although the Melbourne diocese remained intact, St Andrew's was completed to be one of the largest church buildings in Australia; its vast and versatile space has been described as the "Cathedral of Light".[2]

St Andrew's maintains close and historic ties with both Brighton Grammar School and Firbank Grammar School.

Location

Set amidst an extensive landscaped historic precinct 500 metres from the Brighton beach, the land of St Andrew’s Church is on the eastern side of New Street in Middle Brighton. The church lent its name to the other property boundaries to the south and east: Church Street and St Andrews Street. To the north, St Andrew’s grounds border Brighton Grammar School, as in the 1920s the school received in trust five acres of the original ten acres of land granted to the church in 1841.[1]

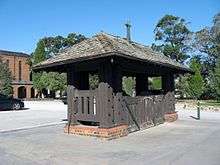

The main church car parking area is entered from New Street, to the north of the corner of Church and New Streets; the entry to the car park is at the site of the rustic timber lych gate, built to the west of the church in 1926 in the Arts and Crafts style and possibly designed by Louis Williams.[1]

Early history

Ten acres of land were set aside as a Church of England Reserve in the Brighton estate planned by Henry Dendy and Jonathan Binns Were in 1841.[1] This "Church Reserve" site was located in a small township of fashionable crescents, between the outer crescent and desirable allotments that ran to Port Phillip Bay.

Foundation: 1842

In 1842, the earliest recorded Anglican church service was held near the corner of New Street and Well Street, in the home owned by Henry Dendy.[2] The Revd Adam Compton Thomson, the only Anglican priest in the Port Phillip District at the time, was the first to minister to the Brighton congregation.[3]

Graveyard: 1843

On 24 October 1843, the two-acre St Andrew's Graveyard, established to the north-east of the first building, was consecrated by Bishop William Grant Broughton, the first and only Bishop of Australia. The graveyard was the first portion of the existing church land to be used for religious purposes and is a rare surviving example in Victoria of a pre-gold rush graveyard.[2] The first burial took place the following year, well before the opening of the Brighton General Cemetery in 1855, and St Andrew's Cemetery was the major burial ground for the district. More than 300 burials took place, mostly before 1860, and the graves of many district pioneers are located in the graveyard. After over 100 years of interments, the last burial took place in 1948. However, the adjoining garden of remembrance, established in 1953, remains in use.[2] The St Andrew's Graveyard is one of only four remaining churchyard cemeteries in Melbourne.[4]

Original buildings

First church and school building: 1842

A small wooden building, erected to the south of the site in 1842 as No. 1 St Andrews Street, was used as a church and school. However, the north-western extension of Church Street, from St Andrews Street to the junction with New Street, isolated the southern portion of the "Church Reserve" from the main site soon after construction. This southern portion was not conveyed to the church in 1843 and other development took place on that land.[1] In 1843, it was recorded that 75 pupils were enrolled at the newly established St Andrew's School, which was officially opened as School No. 44 in 1849 by Church of England authorities.[5]

Second church building: 1850

A rectangular ironstone church, designed by architect, Melbourne city surveyor and St Andrew's parishioner, Charles Laing,[6] was erected to the north-west of the St Andrew’s Graveyard in 1850. Although no drawings of this second church building survive, the architectural style was probably rudimentary Gothic.[2] In the late 1920s, the present Vicarage was built on the site of this second church building.[1]

Third church building and school house: 1857

By 1857, the congregation had outgrown the second church building.[2] The parishioner, Brighton resident and prolific Melbourne architect Charles Webb, and his partner Thomas Taylor, were commissioned to design a new bluestone church, school house and vicarage.[7] "King Webb" designed the new bluestone church in the Early English Gothic style, with a prominent bellcote surmounting the gable, a small gabled western entrance porch, a seven-bay nave and small chancel. Webb's building was considered "one of the more perfect examples of a church of the period in the Colony"[8] and the majority of the building, including the distinctive western facade, remains a Brighton landmark.

The ironstone church building was demolished and some of the stone used in the construction of a T-shaped school house building.[2] St Andrew's School, originally established in the first small wooden church building 15 years earlier, continued to operate in this ironstone school building until 1875 when students were relocated to a new school in Brighton, established after the state school system was introduced in 1872.[5] The school house was then used for Sunday School and other church activities.

In either 1866 or 1886, a north wing was added to the school house building, creating the symmetrical H-shaped building which survives today. Designed in a Gothic Revival style, the symmetrical H-shaped school house is constructed of random coursed, locally quarried ironstone and is roofed in slate. It has projecting gabled end wings, a central projecting entry porch and render detailing that includes parapets, finials, angle buttresses, window and door surrounds and gable vents. When additions were made to the church building in 1886, the altar and furnishings from the demolition of the chancel were installed in the central space of the school house.[5] The building is currently used as a café and coffee shop.

St Andrew's School House is of architectural and historical significance to the State of Victoria as one of the few surviving examples of Charles Webb's distinctive institutional buildings, as a rare example of a building constructed of local ironstone and as a rare surviving example of a substantial early denominational school building.[5]

Third church building enlargement: 1886

In the 1860s and 1870s, Brighton further expanded as a desirable beach-side suburb and by 1886 necessary additions were made to the church.

Large sandstone transepts and an apsidal chancel were added to the existing bluestone church by 'probably the best known figure in the architectural profession in Melbourne',[9] architect Lloyd Tayler. Built in the High Victorian Gothic style, and constructed of Oamaru limestone from New Zealand, Charles Webb's bluestone church served as the nave in the enlarged building.[2]

As the simpler Early English Gothic and decorated High Victorian Gothic architectural styles were not considered visually compatible,[2] there was provision for either replacing the bluestone nave, or cladding it in Oamaru limestone to complement the transepts and chancel.

The 1886 Lloyd Tayler interior featured elaborate woodwork in the sanctuary fittings including a large rood screen and divided choir stalls, and magnificent stained glass windows in the transepts and chancel. The designs for Tayler’s additions, opened in August 1886 and costing £7,000 – a substantial sum for the time, were clearly influenced by the most prolific 19th century Gothic Revivalists, including A.W.N. Pugin and Sir George Gilbert Scott.[2]

Parish hall: 1928

In 1928, St Andrew’s Parish Hall, designed by architect Louis Williams, was built to the east of the 19th century school house building. This large Arts and Crafts-influenced building facing St Andrews Street is constructed of clinker brick and the symmetrical front facade contains a broad central jerkinhead gable roof.

The exposed brick interior of the building contains oversized timber hammer beam trusses and large folding timber doors that line both sides of the central hall. All timberwork remains unpainted.[1] The Parish Hall is used daily by numerous organizations for a large variety of events.

Fire: 1961

In 1954, over 70 years after the construction of the transepts and chancel, the nave of Lloyd Tayler’s grand design for the church building had not been completed, and proposals were made by the noted Melbourne architect John F. D. Scarborough to demolish the 1857 bluestone building, still functioning as the nave, and rebuild a wider nave using the bluestone facings and arches.[2]

Scarborough’s proposals did not proceed, and the 1857 nave and 1886 transepts and chancel were largely destroyed by a devastating fire on Sunday evening 19 February 1961. Given the nave timber ceiling over 100 years old, the fire quickly engulfed the building and the damage was such that a restoration was impractical, even had that been considered appropriate.[2]

On 20 February 1961, the day following the fire, the renowned Australian church architect and parishioner, Louis Williams, was appointed to be the architect for a new church building.[2]

Present church complex

The present St Andrew’s Church complex is considered to be among the largest and most impressive church buildings in Australasia. Using over 500,000 bricks and over 16,000 roof tiles, the versatile space consists of three major conjoined internal areas: the main church building, the Pioneer Chapel and the lady chapel.[2]

The present church building, a Melbourne landmark, was dedicated on 15 December 1962 in the presence of the Governor of Victoria, Sir Dallas Brooks; the Archbishop of Melbourne, the Most Reverend Sir Frank Woods; other clergy and two thousand people.[1]

Main church

As it was decided to retain the west end and four bays from the nave of Charles Webb’s bluestone church built in 1857, the main section of the new church building, incorporating a new nave, transepts and sanctuary, was re-orientated and set at a right angle to the bluestone building, so the new nave was built on a north-south axis rather than the traditional liturgical east-west.[2]

Sir Edward Maufe’s design for Guildford Cathedral in England, consecrated in 1961, was held up as “an example of good taste”[2] for the design of the new St Andrew’s Church and many of Louis Williams' personal ecclesiastical design ideas are also apparent at St Andrew's. Williams retained “the traditional layout of an Anglican church favoured by ecclesiologists in the 19th century and following the pre-Reformation pattern”,[2] and used a modern Gothic style for overall design with modern materials and construction methods. Williams had used this conservative approach frequently and successfully in other smaller buildings in suburban Melbourne and country Victoria.[2]

Williams’ desire for extremely generous planning is manifest throughout the main church with well-spaced pews, a clear view of the altar, wide aisles, a vast sanctuary and a large choir and organ gallery at the rear with a spacious narthex below. The narthex's low ceiling emphasises the height of the nave and sanctuary, "which is obvious as one enters the body of the church and the walls seem to rise in an impressive upsurge - 'an offering of height'."[8]

The windowless recessed sanctuary wall, lit by concealed clear side windows, was originally intended to be enriched with a reredos of Venetian vitreous mosaic, "rising towards its summit in a stirring outburst of joyous, expressive colour". The commissioning of this large and colourful mosaic, however, was deferred and finished instead with a large cross. The sanctuary recess now features a bronze sculpture of the prodigal son by Guy Boyd below this "temporary" cross. The sculpture was installed in 1987, the new church building’s 25th anniversary.[2]

The main church building, of cruciform shape with shallow transepts, has a steel frame; red autumn-tinted "ripple-tex" brick was used for the exterior and hard-faced "oatmeal"-coloured cream brick for the interior. The dimensions are spacious: the building is almost 200 feet long and the nave is nearly 50 feet high with a distinctive ceiling of golden anodised aluminium tiles. Externally, the copper flèche over the crossing is nearly 120 feet high.

The nave of the present building, the “Cathedral of Light”, is a vast light-filled space. Large stained glass windows and travertine piers dominate the cream brick walls; clear glass doors, placed the entire length of one side of the nave, open to the cloister garden.

. Many artistic features in the main building are the result of the close collaboration between Louis Williams and the Dutch-Australian artist Rein Slagmolen of Vetrart Studios, including the brass representations of the Four Evangelists on the 'Polylite' pulpit and lectern panels, the copper font cover featuring a dove and vine leaves, and the "Tree of Life" west window.

Using the German-made "antique" stained glass favoured by Williams, the windows in the nave are toned from quiet and cooler colours to richer and warmer colours as they progress to the sanctuary and the intended artistic highlight of the main building, the vibrant and multi-coloured sanctuary mosaic. The stained glass in the main building is non-figurative, relying instead on the colour gradation of the leadlight to imply symbolic references.

The sanctuary and baptistery windows are predominantly deep blues, greens and reds, while the large Tree of Life west window, by Rein Slagmolen, at the opposite end of the building, uses cool blues at the base rising to warm golds at the top of the window.

The west window tracery was designed to suggest the branching of a tree; the impression is enhanced by the inclusion of leaf-shaped russet-coloured glass at the apex of the window and the large double-winged organ cases branching out from the "tree".[2]

The south transept features a large and richly traceried rose window above the exposed pipework of the Transept division of the pipe organ; the rose window tracery, with its "leaf-like pattern" also provides a subtle link to the 'Tree of Life' west window.[8]

The interior of the main church building stands as a testament to Williams’ intention to make the present St Andrew’s nave “a symphony of light and colour”[2] as distant as possible from the “dim religious light of the Victorian era”.[2]

All the furniture and furnishings within the church building were made to Williams' designs, and represent one of the largest collections of mid 20th century ecclesiastical furniture in Australia.

Pioneer Chapel

The old bluestone nave built in 1857, in Early English Gothic style and typical of the work of Charles Webb, remains as the Pioneer Memorial Chapel. In 1961, in order to reconcile the proportions of the old bluestone nave and convert it to its present use as a chapel and baptistery, three bays of the original seven-bay bluestone nave were demolished.[2]

Externally, the Pioneer Chapel is linked to the narthex of the new building by a large arcaded cloister with an internal cloister garden, extremely rare in any cathedral or church in Australasia.

Significantly, the original west end of the 1857 bluestone church building, a distinctive Brighton landmark with its prominent bellcote, bracketed string course, triple lancet window tracery, pinnacled corner buttresses and original main entrance porch remains as the symmetrical western façade of the Pioneer Chapel.[1]

As the original triple lancet west window was destroyed in the 1961 fire, the opportunity was taken to commission a mural from the leading one-armed Australian muralist Napier Waller to complete the internal western wall of the Chapel; externally, the stone tracery remains with blacked-in stone. The Pioneer Memorial Mural depicts the “pioneers of Brighton landing from Port Phillip Bay and setting about the task of building a new church.”[2]

Lady Chapel

This intimate space, to the north-west of the crossing in the main church, was designed as the Chapel of the Incarnation. The stained glass windows, by David Taylor Kellock, a Scottish-trained Ballarat artist favoured by Louis Williams, represent “the work of Christ and His Church in the redemption of the world in all its aspects”.[2]

The Lady Chapel windows are among the most successful examples of Kellock's work;[10] the repetition of the "Tree of Life" west window "tree-form" tracery within the stained glass unifies these figurative windows with the non-figurative windows of the main building and gave Kellock the basic composition for each scene.[10]

In addition to the six Kellock stained glass windows, the Lady Chapel also houses a notable dossal (“The Crowning of the Virgin”) and altar frontal (“There is a Green Hill far away”) by Beryl Dean, considered by some as the leading ecclesiastical textile artist in the world during the second half of the 20th century.[2]

Clergy

Many of the vicars of St Andrew's Church have been appointed bishops after their ministry at St Andrew's. Since 1980, the vicars of St Andrew's have formerly been deans of cathedrals in dioceses in Tasmania, New South Wales and New Zealand.

Vicars of St Andrew's Church, Brighton

- 1842-1848: The Revd Adam Compton Thomson[3]

- 1849-1853: The Revd William Brickwood

- 1853-1889: The Revd Samuel Taylor (the parish's longest serving vicar; Taylor was vicar for 36 years)

- 1889-1892: Canon William Chalmers (later Bishop of Goulburn, New South Wales)[11]

- 1892-1894: The Revd John "Jack" Stretch (later Bishop of Newcastle, New South Wales)[12]

- 1894-1899: The Revd Reginald Stephen (later Bishop of Tasmania and then Bishop of Newcastle),[13]

- 1899-1913: The Revd Edward Crawford

- 1913-1917: The Revd Archibald Law (later vicar of St John's Church, Toorak, Melbourne)

- 1918-1928: Canon William Hancock (later Archdeacon of Melbourne)[14]

- 1928-1948: The Venerable Harold Hewett

- 1949-1951: The Revd Donald Redding MBE (later Bishop of Bunbury and Coadjutor Bishop of Melbourne)

- 1952-1965: The Venerable George "Bill" Codrington

- 1966-1969: The Revd Ross Border

- 1969-1973: The Revd David Shand (later Bishop of St Arnaud, Victoria)

- 1974-1979: The Revd Don Hardy

- 1980-1993: The Revd Harlin Butterley (formerly Dean of St David's Cathedral, Hobart, Tasmania)

- 1993-2003: The Revd Ken Hewlett (formerly Dean of Bathurst Cathedral, New South Wales)

- 2004-2011: The Revd Kenyon McKie (formerly Dean of Goulburn Cathedral, New South Wales)

- 2012–present: The Revd Canon Jan Joustra (formerly Dean of St Peter's Cathedral, Hamilton, New Zealand)

Associate clergy

Many clergy have served at St Andrew's Church as associate priests. The associate priest occupies the curate's house, located adjacent to the vicarage and organist's house. In recent years, retired clergy have also been assisting in the parish in addition to the current assistant priest, Mother Emily Fraser.

- The Revd Richard Harvey (1992-1994) (former curate at St John's Camberwell from 1989-1991 in Melbourne and St Stephen's Belmont from 1991-1992 in Geelong, Harvey served as assistant priest from 1992-1994 at Brighton; he is now residing in New South Wales since 1994 and a full-time teacher, but he continues to be a volunteer associate priest at Holy Trinity, Terrigal as of 2012)

- The Revd Judith Marriott (now serving in Beaumaris)

- The Revd Sam Goodes

- The Revd Chris Lancaster

- Mother Emily Fraser

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 http://vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au/mobile/result_detail/160

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 The Anglican Parish of St Andrew, Brighton: A History in Celebration. Brighton, 2013.

- 1 2 James Grant, "Thomson, Adam Compton (1800–1859)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/thomson-adam-compton-2730/text3851, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 27 January 2015.

- ↑ http://www.foskc.org/pdf/CC23.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.onmydoorstep.com.au/heritage-listing/160/st-andrews-school-house

- ↑ J. L. O'Brien, 'Laing, Charles (1809–1857)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/laing-charles-2318/text3011, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Charles Bridges-Webb, 'Webb, Charles (1821–1898)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/webb-charles-4820/text8039, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Gladys Marie Moore, "Louis Reginald Williams", Masters thesis, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, The University of Melbourne, 2001.

- ↑ Donald James Dunbar and George Tibbits, 'Tayler, Lloyd (1830–1900)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/tayler-lloyd-4689/text7763, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 Bronwyn Hughes, "Twentieth Century Stained Glass in Melbourne Churches", Masters thesis, Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne, 1997.

- ↑ B. R. Marshall, 'Chalmers, William (1833–1901)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chalmers-william-3188/text4783, published first in hardcopy 1969, accessed online 1 February 2015.

- ↑ K. J. Cable, 'Stretch, John Francis (Jack) (1855–1919)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/stretch-john-francis-jack-8699/text15223, published first in hardcopy 1990, accessed online 1 February 2015.

- ↑ K. J. Cable, 'Stephen, Reginald (1860–1956)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/stephen-reginald-8641/text15105, published first in hardcopy 1990, accessed online 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Stan Moss, 'Hancock, William (1863–1955)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hancock-william-6547/text11251, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online 27 January 2015.