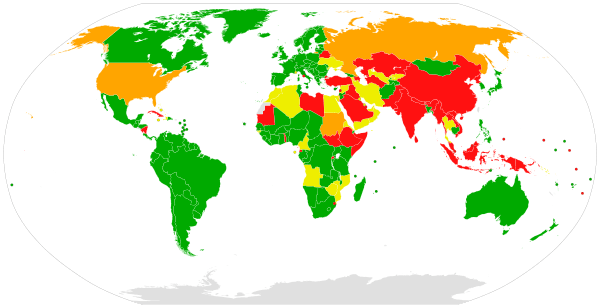

States parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The states parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court are those sovereign states that have ratified, or have otherwise become party to, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Rome Statute is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court, an international court that has jurisdiction over certain international crimes, including genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes that are committed by nationals of states parties or within the territory of states parties. States parties are legally obligated to co-operate with the Court when it requires, such as in arresting and transferring indicted persons or providing access to evidence and witnesses. States parties are entitled to participate and vote in proceedings of the Assembly of States Parties, which is the Court's governing body. Such proceedings include the election of such officials as judges and the Prosecutor, the approval of the Court's budget, and the adoption of amendments to the Rome Statute.

States parties

As of 3 December 2016, 124 states have ratified or acceded to the Rome Statute.[1]

| State party[1] | Signed | Ratified or acceded | Entry into force | Amend. 1[2] | Amend. 2[3] | Amend. 3[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

— | 10 February 2003 | 1 May 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 31 January 2003 | 1 May 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 30 April 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

23 October 1998 | 18 June 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

8 January 1999 | 8 February 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

9 December 1998 | 1 July 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 28 December 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

16 September 1999 | 23 March 2010 | 1 June 2010 | — | — | — |

| |

8 September 2000 | 10 December 2002 | 1 March 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

10 September 1998 | 28 June 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

5 April 2000 | 5 April 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

24 September 1999 | 22 January 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 27 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

8 September 2000 | 8 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

7 February 2000 | 20 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

11 February 1999 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

30 November 1998 | 16 April 2004 | 1 July 2004 | — | — | — |

| |

13 January 1999 | 21 September 2004 | 1 December 2004 | — | — | — |

| |

23 October 2000 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 December 1998 | 7 July 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

28 December 2000 | 10 October 2011 | 1 January 2012 | — | — | — |

| |

12 December 1999 | 3 October 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

20 October 1999 | 1 November 2006 | 1 January 2007 | — | — | — |

| |

11 September 1998 | 29 June 2009 | 1 September 2009 | Ratified | Ratified | — |

| |

10 December 1998 | 5 August 2002 | 1 November 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

22 September 2000 | 18 August 2006 | 1 November 2006 | — | — | — |

| |

8 September 2000 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 3 May 2004 | 1 August 2004 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 18 July 2008 | 1 October 2008 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 7 June 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

30 November 1998 | 15 February 2013 | 1 May 2013 | — | — | — |

| |

12 October 1998 | 21 May 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

15 October 1998 | 7 March 2002 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

13 April 1999 | 21 July 2009 | 1 October 2009 | In force | In force | — |

| |

25 September 1998 | 21 June 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 5 November 2002 | 1 February 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 12 February 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

8 September 2000 | 12 May 2005 | 1 August 2005 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 6 September 2002 | 1 December 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 5 February 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 3 March 2016 | 1 June 2016 | Ratified | Ratified | — |

| |

27 December 1999 | 30 January 2002 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

29 November 1999 | 29 November 1999 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 29 December 2000 | 1 July 2002 | Ratified | Ratified | Ratified |

| |

18 July 1998 | 9 June 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

22 December 1998 | 20 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

4 December 1998 | 28 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 5 September 2003 | 1 December 2003 | In force | In force | — |

| |

10 December 1998 | 11 December 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 20 December 1999 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 15 May 2002 | 1 August 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 19 May 2011 | 1 August 2011 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 2 April 2012 | 1 July 2012 | — | — | — |

| |

7 September 2000 | 14 July 2003 | 1 October 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

28 December 2000 | 24 September 2004 | 1 December 2004 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 1 July 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

15 January 1999 | 30 November 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

26 August 1998 | 25 May 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | Ratified | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 26 July 1999 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 17 July 2007 | 1 October 2007 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

11 August 1999 | 15 March 2005 | 1 June 2005 | — | — | — |

| |

8 March 2000 | 13 November 2002 | 1 February 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

22 April 1999 | 28 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

30 November 1998 | 6 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 22 September 2004 | 1 December 2004 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 2 October 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

10 December 1998 | 12 May 2003 | 1 August 2003 | Ratified | Ratified | — |

| |

13 October 1998 | 8 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 6 March 2002 | 1 July 2002 | Ratified | Ratified | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 14 March 2008 | 1 June 2008 | — | — | — |

| |

2 March 1999 | 19 September 2002 | 1 December 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 21 September 2011 | 1 December 2011 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 16 August 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 29 November 2002 | 1 February 2003 | In force | In force | — |

| |

6 September 2000 | 7 December 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

11 November 1998 | 5 March 2002 | 1 July 2002 | In force | — | — |

| |

7 September 2000 | 28 October 2005 | 1 January 2006 | — | — | — |

| |

8 September 2000 | 12 October 2010 | 1 January 2011 | — | — | — |

| |

29 December 2000 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 23 October 2006 | 3 June 2006 | — | — | — |

| |

27 October 1998 | 25 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

13 December 2000 | 12 November 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 17 July 2001 | 1 July 2002 | Ratified | Ratified | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 7 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

1 June 2000 | 27 September 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

28 August 1998 | 16 February 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | — | Ratified |

| |

— | 2 January 2015 | 1 April 2015 | — | Ratified | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 21 March 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 14 May 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 December 2000 | 10 November 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

28 December 2000 | 30 August 2011 | 1 November 2011 | — | — | — |

| |

9 April 1999 | 12 November 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 5 February 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

7 July 1999 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 22 August 2006 | 1 November 2006 | — | — | — |

| |

27 August 1999 | 18 August 2010 | 1 November 2010 | — | — | — |

| |

— | 3 December 2002 | 1 March 2003 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 16 September 2002 | 1 December 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 13 May 1999 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 2 February 1999 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

19 December 2000 | 6 September 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

28 December 2000 | 10 August 2010 | 1 November 2010 | — | — | — |

| |

17 October 1998 | 15 September 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

23 December 1998 | 11 April 2002 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | Ratified |

| |

7 October 1998 | 31 December 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 27 November 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 24 October 2000 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

— | 15 July 2008 | 1 October 2008 | — | — | — |

| |

7 October 1998 | 28 June 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

18 July 1998 | 12 October 2001 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

29 December 2000 | 20 August 2002 | 1 November 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

30 November 1998 | 5 May 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

23 March 1999 | 6 April 1999 | 1 July 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

— | 24 June 2011 | 1 September 2011 | — | — | — |

| |

17 March 1999 | 14 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

30 November 1998 | 4 October 2001 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

19 December 2000 | 28 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | In force | In force | — |

| |

— | 2 December 2011 | 1 February 2012 | — | — | — |

| |

14 October 1998 | 7 June 2000 | 1 July 2002 | — | — | — |

| |

17 July 1998 | 13 November 2002 | 1 February 2003 | — | — | — |

Withdrawal

Article 127 of the Rome Statute allows for states to withdraw from the ICC. Withdrawal takes effect one year after notification of the depositary, and has no effect on prosecution that has already started. As of November 2016 three states have given formal notice of their intention to withdraw from the statute.[1]

| State party[1] | Signed | Ratified or acceded | Entry into force | Withdrawal notified | Withdrawal effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

13 January 1999 | 21 September 2004 | 1 December 2004 | 27 October 2016 | 27 October 2017 |

| |

4 December 1998 | 28 June 2002 | 1 September 2002 | 10 November 2016 | 10 November 2017 |

| |

17 July 1998 | 27 November 2000 | 1 July 2002 | 19 October 2016 | 19 October 2017 |

These states, and several others contemplating withdrawing, have argued that it is a tool of Western imperialism, only punishing leaders from small, weak states while ignoring crimes committed by richer and more powerful states.[10][11][12] This sentiment has been expressed particularly by African states, 34 of which are members of the ICC, due to a perceived disproportionate focus of the Court on Africa. Nine out of the ten situations which the ICC has investigated were in African countries.[13][14]

In June 2009, several African states, including Comoros, Djibouti, and Senegal, called on African states parties to withdraw en masse from the statute in protest against the indictment of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.[15] In September 2013, Kenya's National Assembly passed a motion to withdraw from the ICC in protest against the ICC investigation in Kenya.[16] A mass withdrawal from the ICC by African member states in response to the trial of Kenyan authorities was discussed at a special summit of the African Union in October.[17] The summit concluded that serving heads of state should not be put on trial, and that the Kenyan cases should be deferred.[18] However, the summit did not endorse the proposal for a mass withdrawal due to lack of support for the idea.[19] In November the ICC's Assembly of State Parties responded by agreeing to consider proposed amendments to the Rome Statute to address the AU's concerns.[20]

The prosecution of Kenyan Deputy President William Ruto and President Uhuru Kenyatta (both charged before coming into office) led to the Kenyan parliament passing a motion calling for Kenya's withdrawal from the ICC. Gambia submitted it's formal notice of withdrawal on 10 November 2016. However, a few weeks later a presidential election ended the long rule of Yahya Jammeh in favour of Adama Barrow, who pledged to remain a member of the ICC.[21]

Implementing legislation

The Rome Statute obliges states parties to cooperate with the Court in the investigation and prosecution of crimes, including the arrest and surrender of suspects.[22] Part 9 of the Statute requires all states parties to “ensure that there are procedures available under their national law for all of the forms of cooperation which are specified under this Part”.[23]

Under the Rome Statute's complementarity principle, the Court only has jurisdiction over cases where the relevant state is unwilling or unable to investigate and, if appropriate, prosecute the case itself. Therefore, many states parties have implemented national legislation to provide for the investigation and prosecution of crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of the Court.[24]

As of April 2006, the following states had enacted or drafted implementing legislation:[25]

| States | Complementarity legislation | Co-operation legislation |

|---|---|---|

| Australia, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom | Enacted | Enacted |

| Colombia, Congo, Serbia, Montenegro | Enacted | Draft |

| Burundi, Costa Rica, Mali, Niger, Portugal | Enacted | None |

| France, Norway, Peru, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland | Draft | Enacted |

| Austria, Japan, Latvia, Romania | None | Enacted |

| Argentina, Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dominica, Gabon, Ghana, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Lesotho, Luxembourg, Nigeria, Samoa, Senegal, Uganda, Uruguay, Zambia | Draft | Draft |

| Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Hungary, Jordan, Panama, Venezuela | Draft | None |

| Mexico | None | Draft |

| Afghanistan, Albania, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cyprus, Djibouti, Fiji, the Gambia, Guinea, Guyana, Liberia, Malawi, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Mongolia, Namibia, Nauru, Paraguay, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, San Marino, Sierra Leone, The Republic of Macedonia, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste, United Republic of Tanzania | None | None |

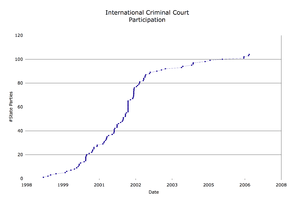

Summary of signatures and ratifications/accessions

| Date | Signatures | |

| December 31, 1998 | 72 | |

| December 31, 1999 | 93 | |

| December 31, 2000 | 139 | |

| Date | Ratifications/accessions | Remaining signatories |

| December 31, 1998 | 0 | 72 |

| December 31, 1999 | 6 | 87 |

| December 31, 2000 | 27 | 112 |

| December 31, 2001 | 48 | 92 |

| December 31, 2002 | 87 | 55 |

| December 31, 2003 | 92 | 51 |

| December 31, 2004 | 97 | 46 |

| December 31, 2005 | 100 | 43 |

| December 31, 2006 | 104 | 41 |

| December 31, 2007 | 105 | |

| December 31, 2008 | 108 | 40 |

| December 31, 2009 | 110 | 38 |

| December 31, 2010 | 114 | 34 |

| December 31, 2011 | 120 | 32 |

| December 31, 2012 | 121 | |

| December 31, 2013 | 122 | 31 |

| December 31, 2014 | ||

| December 31, 2015 | 123 | |

| March 3, 2016 | 124 | |

Allocation of judges

The number of states parties from the several United Nations regional groups has an influence on the minimum number of judges each group is allocated. Paragraph 20(b) of the Procedure for the nomination and election of judges of the Court[26] states that any of the five regional groups shall have at least two judges on the court. If, however, a group has more than 16 states parties, there is a third judge allocated to that group.

The following table lists how many states parties there are from each regional group. After the accession of the Maldives on 1 December 2011, the Asian Group has become the last regional group to have three judges allocated. This already had consequences for the ICC judges election, 2011.[27]

| Group | Number of states parties | Number of judges allocated |

| African Group | 34 | 3 |

| Asian Group | 19 | 3 |

| Eastern European Group | 18 | 3 |

| Latin American and Caribbean Group | 27 | 3 |

| Western European and Others Group | 25 | 3 |

Acceptance of jurisdiction

Pursuant to article 12(3) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, a state that is not a party to the Statute may, "by declaration lodged with the Registrar, accept the exercise of jurisdiction by the Court with respect to the crime in question." The state that does so is not a State Party to the Statute, but the Statute is in force for the state as if it had ratified the Statute, only on an ad hoc basis. However, a state that lodges an article 12(3) declaration cannot refer a situation to the Court. This means that the Prosecutor can only open an official investigation after a State Party or the United Nations Security Council refer the situation to the Court. Alternatively, the Prosecutor can open an investigation after a Pre-Trial Chamber gives its consent to do so, but only after it is presented with preliminary evidence.

To date, the Court has made public five article 12(3) declarations. Additionally, a declaration was submitted in December 2013 by the Freedom and Justice Party of Egypt seeking to accept jurisdiction on behalf of Egypt. However, the Office of the Prosecutor found that as the party has lost power following the 2013 Egyptian coup d'état that July, it did not have the authority to make the declaration.[28][29]

| State[30] | Date of acceptance | Start of jurisdiction | End of jurisdiction |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

18 April 2003 | 19 September 2002 | Indefinite |

| |

21 January 2009 | 1 July 2002 | Indefinite |

| |

9 April 2014 | 21 November 2013 | 22 February 2014 |

| |

31 December 2014 | 13 June 2014 | Indefinite |

| |

8 September 2015 | 20 February 2014 | Indefinite |

| Italicized entries signify that declaration has been deemed invalid by the Office of the Prosecutor. |

Signatories which have not ratified

Of the 139 states that had signed the Rome Statute, 31 have not ratified.[1]

| State[1] | Signature |

|---|---|

| |

28 December 2000 |

| |

7 October 1998 |

| |

1 October 1999 |

| |

29 December 2000 |

| |

11 December 2000 |

| |

17 July 1998 |

| |

26 December 2000 |

| |

7 October 1998 |

| |

12 September 2000 |

| |

26 February 1999 |

| |

31 December 2000 |

| |

31 December 2000 |

| |

8 September 2000 |

| |

8 September 2000 |

| |

8 December 1998 |

| |

18 July 1998 |

| |

8 September 2000 |

| |

28 December 2000 |

| |

20 December 2000 |

| |

13 September 2000 |

| |

28 December 2000 |

| |

3 December 1998 |

| |

8 September 2000 |

| |

29 November 2000 |

| |

2 October 2000 |

| |

20 January 2000 |

| |

27 November 2000 |

| |

31 December 2000 |

| |

29 December 2000 |

| |

28 December 2000 |

| |

17 July 1998 |

| * | = States which have declared that they no longer intend to ratify the treaty |

According to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, a state that has signed but not ratified a treaty is obliged to refrain from "acts which would defeat the object and purpose" of the treaty. However, these obligations do not continue if the state has "made its intention clear not to become a party to the treaty".[42] Four signatory states (Israel, Russia, Sudan, and the United States) have informed the UN Secretary General that they no longer intend to become parties to the Rome Statute, and as such have no legal obligations arising from their signature.

Bahrain

The government of Bahrain originally announced in May 2006 that it would ratify the Rome Statute in the session ending in July 2006.[43] By December 2006 the ratification had not yet been completed, but the Coalition for the International Criminal Court said they expected ratification in 2007.[44]

Israel

Israel voted against the adoption of the Rome Statute but later signed it for a short period. In 2002, Israel notified the UN Secretary General that it no longer intended to become a party to the Rome Statute, and as such, they has no legal obligations arising from their signature of the statute.[45]

Israel states that it has "deep sympathy" with the goals of the Court. However, it has concerns that political pressure on the Court would lead it to reinterpret international law or to "invent new crimes". It cites the inclusion of "the transfer of parts of the civilian population of an occupying power into occupied territory" as a war crime as an example of this, whilst at the same time disagrees with the exclusion of terrorism and drug trafficking. Israel sees the powers given to the prosecutor as excessive and the geographical appointment of judges as disadvantaging Israel which was prevented from joining any of the UN Regional Groups.[46]

Kuwait

At a conference in 2007, the Kuwaiti Bar Association and the Secretary of the National Assembly of Kuwait, Hussein Al-Hereti, called for Kuwait to join the Court.[47]

Russia

Russia signed the Rome Statute in 2000. In November 2016, a presidential decree by Russian President Vladimir Putin approved "sending the Secretary General of the United Nations notice of the intention of the Russian Federation to no longer be a party to the Rome Statute".[48][49] Formal notice was given on 30 November.[50]

Thailand

Former Senator Kraisak Choonhavan called in November 2006 for Thailand to ratify the Rome Statute and to accept retrospective jurisdiction, so that former premier Thaksin Shinawatra could be investigated for crimes against humanity connected to 2,500 alleged extrajudicial killings carried out in 2003 against suspected drug dealers.[51]

Ukraine

A 2001 ruling of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine held that the Rome Statute is inconsistent with the Constitution of Ukraine.[52] Notwithstanding, in October 2006, the Ambassador to the United Nations stated that the Ukrainian government would submit a bill to the parliament to ratify the Statute.[53] Ukraine ratified Agreement on the Privileges and Immunities of the Court (APIC) without having ratified the Rome Statute on 2007-01-29.[54] On 4 April 2012, the Foreign Minister of Ukraine told the President of the International Criminal Court that "Ukraine intends to join the Rome Statute once the necessary legal preconditions have been created in the context of the upcoming review of the country’s constitution."[55] A bill to make the necessary constitutional amendments was tabled in Parliament in May 2014.[56][57] Article 8 of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement, which was signed in 2014, requires Ukraine to ratify the Rome Statute. In 2016 the Ukrainian parliament adopted the necessary constitutional amendments to allow for ratification of the treaty, however they will not enter into force for three years.[58]

United States

There is presently bipartisan consensus that the United States does not intend to ratify the Rome Statute.[59] Some US Senators have suggested that the treaty could not be ratified without a constitutional amendment.[60] Therefore, US opponents of the ICC argue that the US Constitution in its present form does not allow a cession of judicial authority to any body other than the Supreme Court. In the view of proponents of the ICC there is no inconsistency with the US Constitution, arguing that the role of the US Supreme Court as final arbiter of US law would not be disturbed. Before the Rome Statute, opposition to the ICC was largely headed by Republican Senator Jesse Helms.[61] Other objections to ratification have included that it violates international law, is a political court without appeal, denies fundamental American human rights, denies the authority of the United Nations, and would violate US national sovereignty.

Although the US originally voted against the adoption of the Rome Statute, President Bill Clinton unexpectedly reversed his position on 31 December 2000 and signed the treaty,[62][63] but indicated that he would not recommend that his successor, George W. Bush, submit it to the Senate for ratification.[64] On 6 May 2002, the Bush administration informed the UN Secretary General that the US no longer intended to become a state party and, as such, has no legal obligations arising from their former representatives' signature of the Statute.[65] The country's main objections are interference with their national sovereignty and a fear of politically motivated prosecutions.

In 2002, the US Congress passed the American Servicemembers' Protection Act (ASPA), which contained a number of provisions, including prohibitions on the US providing military aid to countries which had ratified the treaty establishing the Court (exceptions granted), and permitting the President to authorize military force to free any US military personnel held by the Court, leading opponents to dub it the "Hague Invasion Act". The act was later modified to permit US cooperation with the ICC when dealing with US enemies.

The US has also made a number of Bilateral Immunity Agreements (BIAs, also known as "Article 98 Agreements") with a number of countries, prohibiting the surrender to the ICC of a broad scope of persons including current or former government officials, military personnel, and US employees (including non-national contractors) and nationals. None of these agreements preclude the prosecution of Americans by any nation where they are believed to have committed any crime. As of 2 August 2006, the US Department of State reported that it had signed 101 of these agreements.[66] The United States has cut aid to many countries which have refused to sign BIAs.[66]

In 2002, the United States threatened to veto the renewal of all United Nations peacekeeping missions unless its troops were granted immunity from prosecution by the Court.[67] In a compromise move, the Security Council passed Resolution 1422 on 12 July 2002, granting immunity to personnel from ICC non-states parties involved in United Nations established or authorized missions for a renewable twelve-month period.[67] This was renewed for twelve months in 2003 but the Security Council refused to renew the exemption again in 2004, after pictures emerged of US troops abusing Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib, and the US withdrew its demand.[68]

Yemen

On 24 March 2007, the Yemeni parliament voted to ratify the Rome Statute.[69][70] However, some MPs claim that this vote breached parliamentary rules, and demanded another vote. In that further vote, the ratification was retracted.[71]

Non-party, non-signatory states

The deadline for signing the Rome Statute expired following 31 December 2000. States that did not sign before that date have to accede to the Statute in a single step.

Of all the states that are members of the United Nations, observers in the United Nations General Assembly, or otherwise recognized by the Secretary-General of the United Nations as states with full treaty-making capacities,[72] there are 42 which have neither signed nor acceded to the Statute:

Additionally, in accordance with practice and declarations filed with the Secretary-General, the Rome Statute is not in force in the following dependent territories:

-

Guernsey – a Crown dependency of the United Kingdom

Guernsey – a Crown dependency of the United Kingdom -

Jersey – a Crown dependency of the United Kingdom

Jersey – a Crown dependency of the United Kingdom -

Tokelau – a territory of New Zealand

Tokelau – a territory of New Zealand

China

The People's Republic of China has opposed the Court, on the basis that it goes against the sovereignty of nation states, that the principle of complementarity gives the Court the ability to judge a nation's court system, that war crimes jurisdiction covers internal as well as international conflicts, that the Court's jurisdiction covers peacetime crimes against humanity, that the inclusion of the crime of aggression weakens the role of the UN Security Council, and that the Prosecutor's right to initiate prosecutions may open the Court to political influence.[73]

India

The government of India has consistently opposed the Court. It abstained in the vote adopting of the statute in 1998, saying it objected to the broad definition adopted of crimes against humanity; the rights given to the UN Security Council to refer and delay investigations and bind non-states parties; and the use of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction not being explicitly criminalized.[74] Other anxieties about the Court concern how the principle of complementarity would be applied to the Indian criminal justice system, the inclusion of war crimes for non-international conflicts, and the power of the Prosecutor to initiate prosecutions.[75]

Indonesia

Indonesia has stated that it supports the adoption of the Rome Statute, and that “universal participation should be the cornerstone of the International Criminal Court”.[76] In 2004, the President of Indonesia adopted a National Plan of Action on Human Rights, which states that Indonesia intends to ratify the Rome Statute in 2008.[76] This was confirmed in 2007 by Foreign Minister Hassan Wirajuda and the head of the Indonesian People's Representative Council's Committee on Security and International Affairs, Theo L. Sambuaga.[77] In May 2013, Defense Minister Purnomo Yusgiantoro stated that the government needed "more time to carefully and thoroughly review the pros and cons of the ratification".[78]

Iraq

In February 2005 the Iraqi Transitional Government decided to ratify the Rome Statute. However, two weeks later they reversed this decision,[79] a move that the Coalition for the International Criminal Court claimed was due to pressure from the United States.[80]

Lebanon

In March 2009, Lebanese Justice Minister said the government had decided not to join for now. The Coalition for the International Criminal Court claimed this was due in part to "intense pressure" from the United States, who feared it could result in the prosecution of Israelis in a future conflict.[81]

Malaysia

In 2011, Mohamed Nazri Abdul Aziz, the Malaysian minister in charge of Law & Parliamentary Affairs, stated that the government had agreed to ratify the Rome Statute.[82] It reported that, in Malaysia, the cabinet is the authority which can ratify international treaties. As of 2016, the Attorney general was reviewing Malaysia's ratification of the statute.[83]

Nepal

On 25 July 2006, the Nepalese House of Representatives directed the government to ratify the Rome Statute. Under Nepalese law, this motion is compulsory for the Executive.[84]

Following a resolution by Parliament requesting that the government ratify the Statute, Narahari Acharya, Ministry of Law, Justice, Constituent Assembly and Parliamentary Affairs of Nepal, said in March 2015 that it had "formed a taskforce to conduct a study about the process". However, he said that it was "possible only after promulgating the new constitution", which was being debated by the 2nd Nepalese Constituent Assembly.[85][86]

Pakistan

Pakistan has supported the aims of the International Court and voted for the Rome Statute in 1998. However, Pakistan has not signed the agreement on the basis of several objections, including the fact that the Statute does not provide for reservations upon ratification or accession, the inclusion of provisional arrest, and the lack of immunity for heads of state. In addition, Pakistan (which is one of the world's largest supplier of peacekeepers) has, like the United States, expressed reservations about the potential use of politically motivated charges against peacekeepers.[87]

South Sudan

South Sudan's President Salva Kiir Mayardit said in 2013 that the country would not join the ICC.[88]

Turkey

Turkey is currently a candidate country to join the European Union, which has required progress on human rights issues in order to continue with accession talks. Part of this has included pressure, but not a requirement, on Turkey to join the Court which is supported under the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy.[89] Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated in October 2004 that Turkey would "soon" ratify the Rome Statute,[90] and the Turkish constitution was amended in 2004 to explicitly allow nationals to be surrendered to the Court.[91] However, in January 2008, the Erdoğan government reversed its position, deciding to shelve accession because of concerns it could undermine efforts against the Kurdistan Workers Party.[92]

See also

- List of Presidents and Vice-Presidents of the Assembly of States Parties of the International Criminal Court

- European Union and the International Criminal Court

Notes

- ↑ Burundi formally notified the depositary of its intentions to withdraw from the ICC, effective 27 October 2017.[5]

- ↑ Colombia made use of article 124 of the Rome Statute to exempt war crimes committed by its nationals or on its territory from the jurisdiction of the Court for a period of seven years. The relevant declaration came into force with the coming into force of the Rome Statute, for Colombia, on 1 November 2002 and expired on 31 October 2009.

- 1 2 On 1 October 2003 the Ivorian government submitted a declaration, dated 18 April 2003, accepting the Court's jurisdiction for "acts committed on Ivorian territory since the events of 19 September 2002."[6] Côte d'Ivoire subsequently acceded to the Rome Statute, on 15 February 2013, and therefore is now a state party.

- ↑ The Rome Statute entered into force for the Faroe Islands on 1 October 2006 and for Greenland on 1 October 2004.

- ↑ France made use of article 124 of the Rome Statute to exempt war crimes committed by its nationals or on its territory from the jurisdiction of the Court for a period of seven years. The relevant declaration came into force with the coming into force of the Rome Statute, for France, on 1 July 2002. France withdrew its declaration on 13 August 2008 with effect from 15 June 2008.

- ↑ Gambia formally notified the depositary of its intentions to withdraw from the ICC, effective 10 November 2017.[7]

- ↑ Montenegro succeeded to the Rome Statute on 3 June 2006, the date of its independence from Serbia and Montenegro, per a declaration it sent to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, which was received on 23 October 2006.

- ↑ The Rome Statute is not in force for Tokelau.

- 1 2 3 The Palestinian National Authority submitted a declaration on 22 January 2009, dated the previous day, accepting the Court's jurisdiction for "acts committed on the territory of Palestine since 1 July 2002."[31] However, on 3 April 2012 the Prosecutor of the ICC deemed the declaration invalid because the Rome Statute only permits sovereign states to make such a declaration and Palestine was designated an "observer entity" within the United Nations (the body that is the depositary for the Rome Statute) at the time.[32] On 29 November 2012, the United Nations General Assembly voted in favour of recognising Palestine as a non-member observer state.[33] However, in November 2013 the Office of the Prosecutor concluded that this decision did "not cure the legal invalidity of the 2009 declaration."[34] A second declaration accepting the court's jurisdiction was reportedly submitted in July 2014 by Palestine's Justice Minister Saleem al-Saqqa and General Prosecutor Ismaeil Jabr, but the Prosecutor responded that only the Head of State, Head of Government or Minister of Foreign Affairs had the authority to make such a declaration. After failing to receive confirmation from Minister of Foreign Affairs Riyad al-Maliki during an August meeting that the declaration had been made on behalf of the Palestinian government, the Prosecutor concluded that the declaration was invalid because it did not come from an authority with the power to make it.[35] On 2 September 2014, the Prosecutor clarified that if Palestine filed a new declaration, or acceded to the Rome Statute, it would be deemed valid.[36] In December 2014, the assembly of state parties of the ICC recognized Palestine as a "state" without prejudice to any legal or other decisions taken by the court or any other organization.[37][38] A new declaration was submitted 1 January 2015 by Palestine, dated 31 December 2014, accepting the court's jurisdiction effective 13 June 2014.[39] Palestine acceded to the Rome Statute on 2 January 2015, and the prosecutor accepted Palestine as state party. However, the court has not made a ruling on the legal validity of this decision.

- ↑ Canada filed a declaration stating that it does not recognize Palestine as a state and as such it does not consider the Rome Statute to be in force between it and Palestine.[8]

- ↑ South Africa formally notified the depositary of its intentions to withdraw from the ICC, effective 19 October 2017.[9]

- ↑ The Rome Statute entered into force for Akrotiri and Dhekelia; Anguilla; Bermuda; the British Virgin Islands; the Cayman Islands; the Falkland Islands; Montserrat; the Pitcairn Islands; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; and the Turks and Caicos Islands on 11 March 2010. The Statute entered into force for the Isle of Man on 1 February 2013. The Statute entered into force for Gibraltar on 20 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Ukraine submitted a declaration accepting the jurisdiction of the Court for a limited time period on 17 April 2014.[40] Another declaration accepting jurisdiction indefinitely was submitted on 8 September 2015.[41]

- ↑ On 28 August 2002, Israel notified the UN Secretary General that it no longer intended to ratify the treaty and therefore no longer bears any legal obligations arising from its signature.[1]

- ↑ On 30 November 2016, Russia notified the UN Secretary General that it no longer intended to ratify the treaty and therefore no longer bears any legal obligations arising from its signature.[1]

- ↑ On 26 August 2008, Sudan notified the UN Secretary General that it no longer intended to ratify the treaty and therefore no longer bears any legal obligations arising from its signature.[1]

- ↑ On 6 May 2002, the United States notified the UN Secretary General that it no longer intended to ratify the treaty and therefore no longer bears any legal obligations arising from its signature.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. 2016-12-03. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ "Amendment to article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ↑ "Amendments on the crime of aggression to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ↑ "Chapter XVIII, Penal Matters 10.c: Amendment to article 124 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- 1 2 "Reference: C.N.805.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ↑ "Declaration by the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire Accepting the Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court" (PDF). International Criminal Court. 2003-04-18. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- 1 2 "Reference: C.N.862.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 2016-11-11. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ↑ "Depository Notification C.N.57.2015.TREATIES-XVIII.10" (PDF). United Nations. 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- 1 2 "Reference: C.N.786.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ↑ "ICC AND AFRICA - International Criminal Court and African Sovereignty". Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/01/30/ozatp-africa-icc-idAFJOE70T01R20110130 African Union accuses ICC prosecutor of bias

- ↑ "The European Union's Africa Policies". Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Africa and the International Criminal Court: A drag net that catches only small fish?, Nehanda Radio, By William Muchayi, 24 September 2013, http://nehandaradio.com/2013/09/24/africa-and-the-international-criminal-court-a-drag-net-that-catches-only-small-fish/

- ↑ Europe - From Lubanga to Kony, is the ICC only after Africans?. France 24 (2012-03-15). Retrieved on 2014-04-28.

- ↑ African ICC Members Mull Withdrawal Over Bashir Indictment, Voice of America, 2009-06-08

- ↑ "Kenya MPs vote to withdraw from ICC". BBC. 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ "African Union summit on ICC pullout over Ruto trial". BBC News. 2013-09-20. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2013/10/africans-urge-icc-not-try-heads-state-201310125566632803.html

- ↑ Fortin, Jacey (2013-10-12). "African Union Countries Rally Around Kenyan President, But Won't Withdraw From The ICC". International Business Times. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ↑ KABERIA, Judie (2013-11-20). "Win for Africa as Kenya agenda enters ICC Assembly". Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- ↑ "Gambians celebrate after voting out 'billion year' leader". Swissinfo. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Amnesty International, Implementation. Accessed 2007-01-23. See also Article 86 of the Rome Statute

- ↑ Part 9 of the Rome Statute. Accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ [See Article 17 of the Rome Statute

- ↑ Amnesty International, The International Criminal Court: Summary of draft and enacted implementing legislation. Accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Verbal note from the President of the Assembly of States Parties. Retrieved 27 August 2011. From page 3 on, the Procedure for the nomination and election of judges of the International Criminal Court is contained.

- ↑ Note verbale regarding the change of minimum voting requirement for Asia-Pacific states. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "ICC Weekly Update #208" (PDF). International Criminal Court. 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "The determination of the Office of the Prosecutor on the communication received in relation to Egypt". International Criminal Court. 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ "Declarations Art. 12(3)". International Criminal Court. Retrieved 2015-02-01.

- ↑ "Declaration by the Palestinian National Authority Accepting the Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court" (PDF). ICC. 2009-01-21. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ↑ ICC "Prosecutor's Update on the situation in Palestine" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). ICC. 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2014-09-05. - ↑ "Q&A: Palestinians' upgraded UN status". BBC News. 2012-11-30. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ↑ "Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2013" (PDF). Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. 2013-11-25. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ "Is the PA stalling Gaza war crimes probe?". Al Jazeera. 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ↑ Bensouda, Fatou (2014-08-29). "Fatou Bensouda: the truth about the ICC and Gaza". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-09-01.

- ↑ "ASSEMBLY OF STATES PARTIES TO THE ROME STATUTE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT - THIRTEENTH SESSION" (PDF). International Criminal Court. 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2014-12-31.

- ↑ "Hague-based ICC accepts Palestine's status". Al Jazeera. 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ↑ "Declaration accepting the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court" (PDF). International Criminal Court. 2014-12-31. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ↑ "Ukraine accepts ICC jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed between 21 November 2013 and 22 February 2014". ICC. 2014-04-17. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine accepts ICC jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed since 20 February 2014". ICC. 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2015-09-08.

- ↑ Part II §1 Art. 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

- ↑ The ratification and implementation of the Statute of the International Criminal Court in Bahrain, FIDH, 2006-07-10.

- ↑ Rights push for key court pact, Gulf Daily News, 2006-12-21.

- ↑ The American Non-Governmental Organizations Coalition for the International Criminal Court. Ratifications & Declarations. Accessed 2006-12-04.

- ↑ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 30 June 2002. Israel and the International Criminal Court. Accessed 2002-06-30.

- ↑ Lawyers urge Kuwait to become ICC member, Kuwait Times, 2007-03-26, accessed on 2007-04-05

- ↑ "Распоряжение Президента Российской Федерации от 16.11.2016 № 361-рп". President of Russia. 2016-11-26. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ "Russia to Withdraw From the International Criminal Court". The Moscow Times. 2016-11-16. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ "Reference: C.N.886.2016.TREATIES-XVIII.10 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). United Nations. 2016-11-30. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ↑ War on drugs returns to bite Thaksin, Bangkok Post, 2006-11-23

- ↑ "[Decision of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine]" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada. 2001-07-11. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ↑ Statement by Ukraine regarding the Report of the International Criminal Court, UN, 2006-10-09.

- ↑ http://www.iccnow.org/documents/CICC_APIClist_current.pdf

- ↑ ICC President meets Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. ICC. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ "Проект Закону про внесення змін до статті 124 Конституції України (щодо визнання положень Римського статуту)" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ↑ "Проект Закону про внесення змін до статті 124 Конституції України (щодо визнання положень Римського статуту)" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ↑ "Rada amends Constitution of Ukraine in part of justice". Interfax-Ukraine. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- ↑ "Clinton's statement on war crimes court". BBC News. 2000-12-31.

- ↑ "Article III | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ U.S. News & World Report: "The Brief for a World Court, A permanent war-crimes tribunal is coming, but will it have teeth?" By Thomas Omestad; Posted 9/28/97

- ↑ Amnesty International. US Threats to the International Criminal Court. Accessed 2006-11-23.

- ↑ Brett D. Schaefer, 9 January 2001. Overturning Clinton's Midnight Action on the International Criminal Court. The Heritage Foundation. Accessed 2006-11-23.

- ↑ Curtis A Bradley, May 2002. U.S. Announces Intent Not to Ratify International Criminal Court Treaty. The American Society of International Law. Accessed 2006-11-23.

- ↑ John R Bolton, 6 May 2002. International Criminal Court: Letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. US Department of State. Accessed 2006-11-23.

- 1 2 Coalition for the International Criminal Court, 2006. Status of US Bilateral Immunity Acts. Accessed 2006-11-23.

- 1 2 Human Rights Watch, The ICC and the Security Council: Resolution 1422. Accessed 2007-01-11.

- ↑ BBC News, 20 March 2006. Q&A: International Criminal Court. Accessed 2007-01-11.

- ↑ gulfnews.com, 26 March 2007. “Yemen becomes fourth Arab country to ratify ICC statute”. Accessed 27 March 2007.

- ↑ Amnesty International, 27 March 2007. Amnesty International urges Yemen to complete the ratification of the Rome Statute. Accessed 2007-04-01.

- ↑ Almotamar.net, 9 April 2007. “”. Accessed 2021-05-19.

- ↑ "Organs Supplement", Repertory of Practice (PDF) (8), United Nations, p. 10, retrieved 2015-09-20

- ↑ Lu, Jianping; Wang, Zhixiang (2005-07-06). "China's Attitude Towards the ICC". Journal of International Criminal Justice. Oxford University Press. 3 (3): 608–620. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi056. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑ Explanation of vote on the adoption of the Statute of the International Criminal Court, Embassy of India, 1998-07-17

- ↑ Ramanathan, Usha (2005-06-21). "India and the ICC". Journal of International Criminal Justice. Oxford University Press. 3 (3): 627–634. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi055. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 Amnesty International, Fact sheet: Indonesia and the International Criminal Court. DOC, HTML. Accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ RI to join global criminal court, Jakarta Post, 2007-02-11, accessed on 2007-02-11

- ↑ Aritonang, Margareth (2013-05-21). "Govt officially rejects Rome Statute". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ↑ Iraq Pulls Out Of International Criminal Court, Radio Free Europe, 2005-03-02

- ↑ Groups Urge Iraq to Join International Criminal Court, Common Dreams, 2005-08-08

- ↑ Justice campaigners say US urged Lebanon not to join International Criminal Court, Daily Star (Lebanon), 2009-03-12

- ↑ Pandiyan, Veera (2015-01-28). "Ratify the Rome Statute". The Star. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

- ↑ "Kula: Speed up International Criminal Court membership move". 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ Asian Parliamentarians’ Consultation on the Universality of the International Criminal Court, “An action plan for the Working Group of the Consultative Assembly of Parliamentarians for the ICC and the rule of law on the universality of the Rome Statute in Asia”. PDF, HTML 16 August 2006. Accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ "Govt to ratify Rome Statute soon: Minister". República. 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

- ↑ "Wait for consensus cannot exceed two months: Acharya". The Himalayan Times. 2015-03-21. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

- ↑ http://www.amicc.org/docs/Pakistan1422Stmt12June03.pdf

- ↑ McNeish, Hannah (2013-05-23). "South Sudan's President Says 'Never' to ICC". Voice of America. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

- ↑ Council Common Position on the International Criminal Court, American Coalition for the International Criminal Court, 2003-06-13

- ↑ Turkey, EU and the International Criminal Court, Journal of Turkish Weekly, 2005-04-14

- ↑ Constitutional Amendments, Secretariat-General for EU Affairs (Turkey), 2004-05-10

- ↑ Turkey shelves accession to world criminal court, Zaman, 2008-01-20, accessed on 2008-01-20