Cephalopod limb

_on_tentacular_club.jpg)

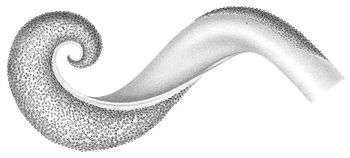

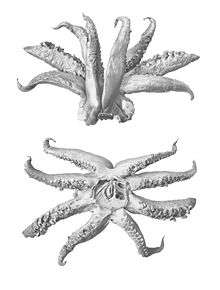

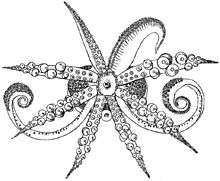

All cephalopods possess flexible limbs extending from their heads and surrounding their beaks. These appendages, which function as muscular hydrostats, have been variously termed arms or tentacles.

Description

In the scientific literature, a cephalopod arm is often treated as distinct from a tentacle, though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Generally, arms have suckers along most of their length, as opposed to tentacles, which have suckers only near their ends.[1] Barring a few exceptions, octopuses have eight arms and no tentacles, while squid and cuttlefish have eight arms and two tentacles.[2] The limbs of nautiluses, which number around 90 and lack suckers altogether, are called tentacles.[2][3][4]

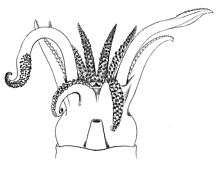

The tentacles of Decapodiformes are thought to be derived from the fourth arm pair of the ancestral coleoid, but the term arms IV is used to refer to the subsequent, ventral arm pair in modern animals (which is evolutionarily the fifth arm pair).[1]

The males of most cephalopods develop a specialised arm for sperm delivery, the hectocotylus.

Anatomically, cephalopod limbs function using a crosshatch of helical collagen fibres in opposition to internal muscular hydrostatic pressure.[5]

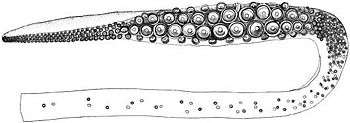

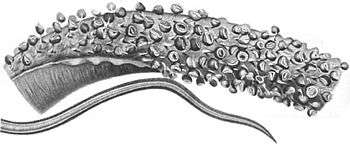

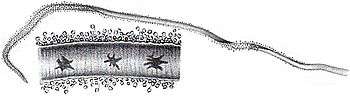

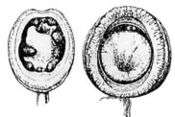

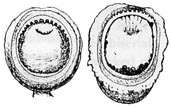

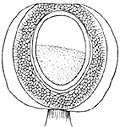

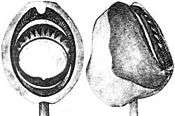

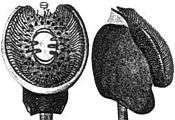

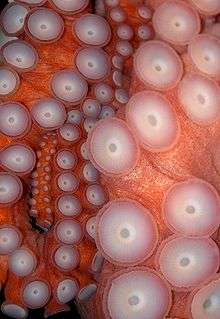

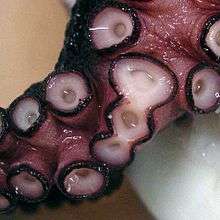

Suckers

Cephalopod limbs bear numerous suckers along their ventral surface as in octopus, squid and cuttlefish arms, or in clusters at the ends of the tentacles, as in squid and cuttlefish.[6] Each sucker is usually circular and bowl-like and has two distinct parts: an outer shallow cavity called an infundibulum and a central hollow cavity called an acetabulum. Both of these structures are thick muscles, and are covered with a chitinous cuticle to make a protective surface.[7] Suckers are used for grasping substratum, catching prey and for locomotion. When a sucker attaches itself to an object, the infundibulum mainly provides adhesion while the central acetabulum is free. Sequential muscle contraction of the infundibulum and acetabulum causes attachment and detachment.[8][9]

Abnormalities

Many octopus arm anomalies have been recorded,[10][11] including a 6-armed octopus (nicknamed Henry the Hexapus), a 7-armed octopus,[12] a 10-armed Octopus briareus,[13] one with a forked arm tip,[14] octopuses with double or bilateral hectocotylization,[15][16] and specimens with up to 96 arm branches.[17][18][19]

Branched arms and other limb abnormalities have also been recorded in cuttlefish,[20] squid,[21] and bobtail squid.[22]

Variability

Cephalopod limbs and the suckers they bear are shaped in many distinctive ways, and vary considerably between species. Some examples are shown below.

Arms

For hectocotylized arms see hectocotylus variability.

| Shape of arm | Species | Family |

|---|---|---|

|

Todarodes pacificus | Ommastrephidae |

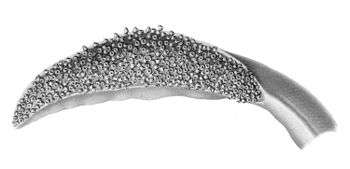

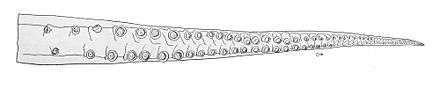

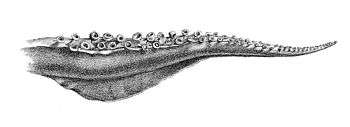

Tentacular clubs

Suckers

References

- 1 2 Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold 1999. Cephalopoda Glossary. Tree of Life web project.

- 1 2 Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 15. "There is some confusion around the terms arms versus tentacles. The numerous limbs of nautiluses are called tentacles. The ring of eight limbs around the mouth in cuttlefish, squids and octopuses are called arms. Cuttlefish and squid also have a pair of specialised limbs attached between the bases of the third and fourth arm pairs [...]. These are known as feeding tentacles and are used to shoot out and grab prey."

- ↑ Fukuda, Y. 1987. Histology of the long digital tentacles. In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 249–256. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_17

- ↑ Kier, W.M. 1987. "The functional morphology of the tentacle musculature of Nautilus pompilius." (PDF). In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 257–269. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_18

- ↑ Inside natures giants, Giant squid episode.

- ↑ von Byern J, Klepal W (2005). "Adhesive mechanisms in cephalopods: a review". Biofouling. 22 (5–6): 329–38. doi:10.1080/08927010600967840. PMID 17110356.

- ↑ Walla G (2007). "A study of the Comparative Morphology of Cephalopod Armature". tonmo.com. Deep Intuition, LLC. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ↑ Kier WM, Smith AM (2002). "The structure and adhesive mechanism of octopus suckers". Integr Comp Biol. 42 (6): 1146–1153. doi:10.1093/icb/42.6.1146.

- ↑ Octopuses & Relatives. "Learn about octopuses & relatives: locomotion". asnailsodyssey.com. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ↑ Kumph, H.E. 1960. Arm abnormality in octopus. Nature 185(4709): 334-335. doi:10.1038/185334a0

- ↑ Toll, R.B. & L.C. Binger 1991. Arm anomalies: cases of supernumerary development and bilateral agenesis of arm pairs in Octopoda (Mollusca, Cephalopoda) Zoomorphology 110(6): 313–316.doi:10.1007/BF01668021

- ↑ Gleadall, I.G. 1989. An octopus with only seven arms: anatomical details. Journal of Molluscan Studies 55: 479–487.

- ↑ Minor birth defect resulting in 10-armed juvenile, all arms fully present and functional. CephBase.

- ↑ Minor birth defect showing bifurcated arm tip. Both tips were fully functional. CephBase.

- ↑ Robson, G.C. 1929. On a case of bilateral hectocotylization in Octopus rugosus. Journal of Zoology 99(1): 95–97. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07690.x

- ↑ Palacio, F.J. 1973. "On the double hectocotylization of octopods." (PDF). The Nautilus 87: 99–102.

- ↑ Okada, Y.K. 1965. On Japanese octopuses with branched arms, with special reference to their captures from 1884 to 1964. Proceedings of the Japan Academy 41(7): 618–623.

- ↑ Okada, Y.K. 1965. Rules of arm-branching in Japanese octopuses with branched arms. Proceedings of the Japan Academy 41(7): 624–629.

- ↑ Monster octopi with scores of extra tentacles. Pink Tentacle, July 18, 2008.

- ↑ Okada, Y.K. 1937. An occurrence of branched arms in the decapod cephalopod, Sepia esculenta Hoyle. Annotated Zoology of Japan 17: 93–94.

- ↑ Bradbury, H.E. & F.A. Aldrich 1971. The occurrence of morphological abnormalities in the oegopsid squid Illex illecebrosus (Lesueur, 1821). Canadian Journal of Zoology 49(3): 377–379. doi:10.1139/z71-055

- ↑ Voss, G.L. 1957. Observations on abnormal growth of the arms and tentacles in the squid genus Rossia. The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 20(2): 129–132.