Suomenlinna

| Suomenlinna Sveaborg | |

|---|---|

|

An aerial view of Suomenlinna. | |

| Location | Helsinki, Finland |

| Coordinates | 60°08′37″N 24°59′04″E / 60.14361°N 24.98444°ECoordinates: 60°08′37″N 24°59′04″E / 60.14361°N 24.98444°E |

| Official name: Fortress of Suomenlinna | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 1991 (15th session) |

| Reference no. | 583 |

| State Party | Finland |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Suomenlinna (Finnish) or Sveaborg (Swedish), until 1918 Viapori (Finnish), is an inhabited sea fortress built on six islands (Kustaanmiekka, Susisaari, Iso-Mustasaari, Pikku-Mustasaari, Länsi-Mustasaari and Långören) and which now forms part of the city of Helsinki, the capital of Finland.

Suomenlinna is a UNESCO World Heritage site and popular with tourists and locals, who enjoy it as a picturesque picnic site. Originally named Sveaborg (Fortress of Svea), or Viapori as called by Finnish-speaking Finns, it was renamed in Finnish to Suomenlinna (Castle of Finland) in 1918 for patriotic and nationalistic reasons, though it is still known by its original name in Sweden and by Swedish-speaking Finns.

The Swedish crown commenced the construction of the fortress in 1748 as protection against Russian expansionism. The general responsibility for the fortification work was given to Augustin Ehrensvärd. The original plan of the bastion fortress was strongly influenced by the ideas of Vauban, the foremost military engineer of the time, and the principles of star fort style of fortification, albeit adapted to a group of rocky islands.

In addition to the island fortress itself, seafacing fortifications on the mainland would ensure that an enemy would not acquire a beach-head from which to stage attacks. The plan was also to stock munitions for the whole Finnish contingent of the Swedish Army and Royal Swedish Navy there. In the Finnish War the fortress surrendered to Russia on May 3, 1808, paving the way for the occupation of Finland by Russian forces in 1809.

The Swedish era

Background

Early on in the Great Northern War, Russia used the Swedish weakness in the Ingermanland and captured the area near river Neva as well as the Swedish forts, Nyen and Nöteborg, built to protect it. In 1703 Peter the Great had founded his new capital, Saint Petersburg, in that furthest-flung corner of the Gulf of Finland. In the approach to it he built the fortified naval base of Kronstadt. Russia soon became a maritime power and a force to be reckoned with in the Baltic Sea. The situation posed a threat to Sweden, which until that time had been the dominant power in the Baltic. This was visibly demonstrated by the use of naval forces in the Russian capture of Viborg in 1710. The main Swedish naval base at Karlskrona was far to the south in accordance with Swedish needs for its navy in the 17th century which often resulted in Swedish ships reaching the coast of Finland only after Russian ships and troops had either started or completed their spring campaigns.[1]

Lack of coastal defenses was keenly felt with Russian landings on spring of 1713 to Helsingfors and with Swedish failure to blockade Hanko Peninsula in 1714. A Russian naval campaign against Swedish coast towards the end of the Great Northern War further outlined the need of developing Finnish coastal defenses. Immediately after the war had ended first plans were set into motion in Sweden to construct an archipelago fleet and a base of operations for it in Finland. However, nothing with regard to Sveaborg took until place until the end of Russo-Swedish War of 1741–1743. Fortifications were left unfinished at Hamina and at Lappeenranta while Hämeenlinna was being built into a supply base. Lack of funds, unwillingness to devote funds for defending Finland and just before the war belief that Russia would be pushed away from the Baltic Sea were the main causes for the lack of progress.[2]

In the following Russo-Swedish War of 1741–1743 which quickly turned from Swedish attack into Russian occupation of Finland again underlined the importance of developing fortifications to Finland. Lack of base of operations for naval forces made it difficult for the Swedish navy to operate in the area.[3] Other European states were also concerned about developments, especially France, with which Sweden had concluded a military alliance. After lengthy debate the Swedish parliament decided in 1747 to fortify the Russian frontier and to establish a naval base at Helsinki as a counter to Kronstadt. The frontier fortifications were established in Svartholm near the small town of Lovisa.[4]

Construction

Sweden started building the fortress in 1748, when Finland was still a part of the Swedish kingdom. Augustin Ehrensvärd (1710–1772) and his gigantic fortification work on the islands off the town of Helsinki brought the district a new and unexpected importance. The fortification of Helsinki and its islands began in January 1748, when Ehrensvärd, as a young lieutenant colonel, came to direct the operations. Fortifications were also built on the Russian side of the new border during the 18th century and some of the Swedish ones were added to.

There were two main aspects to Ehrensvärd's design for the fortress: a series of independent fortifications on each of the linked islands and, at the very heart of the complex, a navy dockyard. Initially the soldiers were housed in the vaults of the fortifications, while the officers had specially built quarters integrated into the baroque cityscape composition of the overall plan. The most ambitious plan was left only half complete: a baroque square on Iso Mustasaari partly based on the model of Place Vendôme in Paris. As the construction work progressed, more residential buildings were built, many following the shape of the fortification lines. Ehrensvärd and some of the other officers were keen artists and painted oil paintings presenting a view of life in the fortress during its construction, and giving the impression of a lively "fortress town" community.

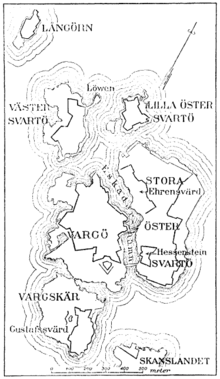

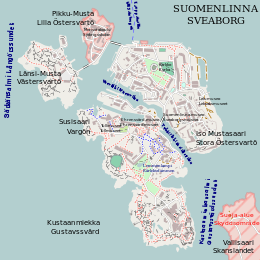

Ehrensvärd's plan contained two fortifications: a sea fortress at Svartholm and place d'armes at Helsingfors. Sveaborg was to be just the sea fortress with additional landside fortifications making up for the rest. Additional plans were made for fortifying the Hanko Peninsula, but these were postponed. Construction started in the spring of 1748 kept expanding and by September had around 2,500 men building them. Due to the repeated Russian threats in 1749 and 1750 more effort was placed on the fortifications on the islands at the expense of the land fortifications to secure a safe base of operations for the Swedish naval units along the Finnish coast. Fortifications spread along the islands Långören (Finnish: Särkkä), Västersvartö (Finnish: Länsi-Mustasaari), Lilla Östersvartö (Finnish: Pikku-Mustasaari), Stora Östersvartö (Finnish: Iso Mustasaari), Vargö (Finnish: Susisaari), and Vargskär (Finnish: Susiluoto), the last of which became known during construction as Gustavssvärd (Finnish: Kustaanmiekka); "Gustav's sword".

Using the military garrisoned in Finland as the workforce, construction continued with over 6,000 workers in 1750. Fortifications at Gustavssvärd were completed in 1751 and the main fortifications on Vargö were ready in 1754 fully operational if unfinished. These accomplishments did not reduce the pace of construction and in 1755 there were 7,000 workers constructing the fortifications outside of Helsingfors which at the time had around 2,000 residents. Swedish participation to the Seven Years' War halted the construction efforts in 1757 which also marks the end of the rapid construction phase of the Sveaborg.[5]

After the 'Cap' party rise to power in 1766 Ehrensvärd was relieved of his post and replaced with ardent 'Cap' supporter Christopher Falkengréen. However, in 1769 when the 'Hat' party again gained power, Ehrensvärd was again placed in command of the Swedish archipelago fleet in Finland, officially arméens flotta ("fleet of the army"). By the time Ehrensvärd died in 1772 no progress had been done at the fortifications. Efforts to improve fortifications continued under Jacob Magnus Sprengtporten, but his tenure was cut short with disagreements with the King Gustav III. Once again efforts slowed down as garrisons were reduced and in 1776 Sveaborg's commander reported that he couldn't even men tenth of the artillery placed to the fort. Even in 1788 at the start of the Russo-Swedish War of 1788–1790 Sveaborg remained in partially incomplete state.[6]

Facilities for constructing ships for the Swedish archipelago fleet were constructed to Sveaborg in the 1760s. In 1764 the first three archipelago frigates launched from Viapori.[7] In addition to the construction of the fortifications and ships, naval officer training was started by Ehrensvärd by his own expense at Sveaborg in 1770. It took until 1779 before a naval military school was formally founded to Sveaborg.[8]

Service

Sveaborg was formed and stocked according to the needs of the Swedish archipelago fleet and was unable to repair and refit the Swedish battlefleet after the battle of Hogland. Facilities were found lacking at Sveaborg especially in the areas intended for taking care of the sick and wounded. Russian control of the waters outside of Sveaborg practically blockaded the Swedish battlefleet to Sveaborg. By cutting the coastal sea route past Hangö, Russians prevented supplies from being shipped from Sweden to the Sveaborg. The Swedish fleet finally managed to set sail for its base at Karlskrona on 20 November when sea had already frozen badly enough that some ships ice had to be sawed open before they could move. Fleet couldn't winter over at Sveaborg since it lacked supplies and facilities for fitting the ships.[9]

While the route to Sweden was open again in late 1788 and in early 1789, Russian ships cut the connection from Sveaborg to Sweden by forming a blockade at Porkkala cape. Sveaborg was the most important location for archipelago fleet's ship construction and fitting in the war. Even then and despite the efforts, several ships remained unfinished until the end of the war at Sveaborg. Importance of the Sveaborg did not escape the Russians whose broad operational plan for 1790 included siege of Sveaborg both from sea and land.[10]

Following a pact between Alexander I and Napoleon, Russia launched a campaign against Sweden and occupied Finland in 1808. The Russians easily took Helsinki in early 1808 and began bombarding the fortress.[11] Its commander, Carl Olof Cronstedt, negotiated a cease-fire. When no Swedish reinforcements had arrived by May, Sveaborg, with almost 7,000 men, surrendered. The reasons for Cronstedt's actions remain somewhat unclear; but the hopeless situation, psychological warfare by the Russians, some (possibly) bribed advisors, fear for the lives of a large civilian population, lack of gunpowder, combined with their physical isolation, are some likely causes for the surrender. By the Treaty of Fredrikshamn in 1809 Finland was ceded from Sweden and became an autonomous grand duchy within the Russian Empire. The Swedish period in Finnish history, which had lasted some seven centuries, came to an end.

Under Russian rule

After taking over the fortress, the Russians started an extensive building program, mostly extra barracks, and extending the dockyard and reinforcement to the fortification lines. The long period of peace following the transfer of power was shattered by the Crimean War of 1853–56. The allies decided to engage Russia on two fronts and sent an Anglo-French fleet to the Baltic Sea. For two summers the fleet shelled the towns and fortifications along the Finnish coast. The bombardment of Suomenlinna (then known as Sveaborg or Viapori) lasted 47 hours and the fortress was badly damaged. They were unable to knock out the Russian guns; after the bombardment the Anglo-French fleet sent no troops ashore and instead set sail for Kronstadt.

After the Crimean War extensive restoration work was begun at Suomenlinna. A new ring of earthworks with artillery emplacements was built at the western and southern edges of the islands.

The next stage in the arming of Suomenlinna and the Gulf of Finland came in the build-up to World War I. The fortress and its surrounding islands became part of "Peter the Great's naval fortification" designed to safeguard the capital, Saint Petersburg.

The fortress became part of an independent Finland in 1917, following the Russian Revolution. After the Finnish Civil War, a prison camp existed on the island.[12]

Present

No longer very practical as a military base, Suomenlinna was turned over to civilian administration in 1973. An independent government department (the Governing Body of Suomenlinna) was formed to administer the unique complex. At the time there was some debate over its Finnish name, with some suggesting that the old name Viapori be restored, but the newer name was retained. The presence of the military on the islands has been drastically scaled down in recent decades. The Suomenlinna garrison houses the Naval Academy (Finnish: Merisotakoulu) of the Finnish Navy. Suomenlinna still flies the war flag, or the swallow-tailed state flag of Finland.

Suomenlinna is now one of the most popular tourist attractions in Helsinki as well as a popular picnicking spot for the city's inhabitants. On a sunny summer day the islands, and in particular the ferries, can get quite crowded. In 2009, a record 713,000 people visited Suomenlinna, most between May and September.[13] A number of museums exist on the island, as well as the last surviving Finnish submarine, Vesikko.

Suomenlinna has always been much more than just a part of Helsinki — it is a town within the town. There are about 900 permanent inhabitants on the islands, and 350 people work there year-round. This is one of the features that makes Suomenlinna unique: the fortress is not simply a museum but a living community.

There is a minimum-security penal labor colony (Finnish: työsiirtola) in Suomenlinna, whose inmates work on the maintenance and reconstruction of the fortifications. Only volunteer inmates who pledge non-use of controlled substances are accepted to the labour colony.

For the general public, Suomenlinna is served by ferries all year, and a service tunnel supplying heating, water and electricity was built in 1982. From the beginning of the 1990s, the tunnel was modified so that it can also be used for emergency transport.

Suomenlinna has been known as an avant-garde location for culture. In the mid-1980s the Nordic Arts Centre was established on the island. Several buildings have been converted into artists' studios, which are let by the administration at reasonable rates. During the summer there is an art school for children. The performances of the Suomenlinna summer theatre regularly draw full houses.

Between 2 and 6 September 2015, the Finnish postal service ran a test of the use of drones to deliver parcels between Helsinki and Suomenlinna. The parcels were limited to 3 kg (7 lb) or less, and flights were under the control of a pilot.[14]

Politics

Results of the Finnish parliamentary election, 2011 in Suomenlinna:

- Green League 23.8%

- Left Alliance 18.8%

- National Coalition Party 17.3%

- Social Democratic Party 16.3%

- Finns Party 14.2%

- Swedish People's Party 2.9%

- Centre Party 2.5%

- Christian Democrats 2.5%

Timeline

- 1748: Building of Sveaborg (Fortress of Svea/Sweden - Swedish), later to be named Suomenlinna in 1918 (Fortress of Finland - Finnish), begins under command of Augustin Ehrensvärd.

- 1808: Sveaborg surrenders to Russia without any opposition during the Finnish War.

- 1809: Treaty of Fredrikshamn: Finland becomes part of Russia.

- 1855: Crimean War: Anglo-French navy bombards Suomenlinna and causes substantial damage.

- 1906: Viapori Rebellion: Russian soldiers plan to depose the tsar.

- 1914-1917: A ring of ground and sea fortifications, called Krepost Sveaborg, is built around Helsinki.

- 1917: Finland becomes independent after the Russian Revolution.

- 1918: Name Suomenlinna becomes official name of the fortress in Finnish, it retains its Swedish name Sveaborg in Swedish. Prison camp of Red rebels is located in Suomenlinna after the Finnish Civil War.

- 1921 Valtion lentokonetehdas (State Aircraft Factory) starts building aeroplanes and powered ice sleighs in Suomenlinna for the Finnish Air Force. In 1936 the factory moves to Tampere.

- 1973: Suomenlinna becomes civil administration area.

- 1991: Suomenlinna becomes UNESCO World Heritage site.

- 1998: Suomenlinna's 250th birthday.

Geography

The Suomenlinna district of Helsinki consists of eight islands. Five of the islands — Kustaanmiekka (which has the greatest concentration of fortifications), Pikku Mustasaari, Iso Mustasaari, Länsi-Mustasaari and Susisaari — are connected by either bridges or sandbars. The unconnected islands are Särkkä, Lonna and Pormestarinluodot. The total land area is 80 hectares (0.8 km²).

Instead of the normal Finnish postal addressing scheme (consisting of a street name and house number), the addresses consist of letter code for island and then a house number. For example, C 83 is house #83 in Iso-Mustasaari (code C). The postal code for the Suomenlinna district is 00190.

In fiction

George R. R. Martin wrote a short story about the surrender of Viapori, "The Fortress", when he was a college student. It was published in his 2007 volume of short stories, Dreamsongs.

See also

- Krepost Sveaborg

- List of fortifications

- List of castles in Finland

- Suomenlinna church

- Vesikko - a submarine anchored at Suomenlinna

- Walhalla-orden

Sources

References

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 13-17,27-47.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 54-55,57-59.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 74-75.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 80-85.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 89-91.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 105-116.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 104.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 122-125.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 138-155.

- ↑ Mattila (1983), p. 155-193.

- ↑ Carl Nordling, L. "Capturing ‘The Gibraltar of the North:’How Swedish Sveaborg was taken by the Russians in 1808." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17.4 (2004): 715-725.

- ↑ Finnish Civil War#Prison camps

- ↑ Helsingin sanomat (Finnish)

- ↑ Reuters - "Finnish post office tests drone for parcel delivery" -accessed 15 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Mattila, Tapani (1983). Meri maamme turvana [Sea safeguarding our country] (in Finnish). Jyväskylä: K. J. Gummerus Osakeyhtiö. ISBN 951-99487-0-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suomenlinna. |

- Suomenlinna official site

- Suomenlinna Historical Society Official Site

- Photographs from Suomenlinna

- Fortifications of Suomenlinna

- More information on Suomenlinna

- Panoramic view of the King's Gate in Suomenlinna

- Sveaborg at Northern Fortress

- Suomenlinna Video

- Picturesque walking tour at Suomenlinna

- Link to satellite imagery of fortifications at Suomenlinna, via Google