Siege of Detroit

Coordinates: 42°19′49″N 83°02′55″W / 42.33015°N 83.04874°W

| Siege of Detroit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

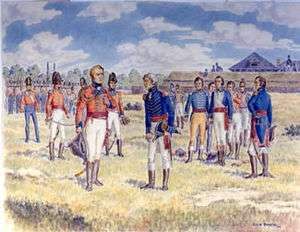

The Surrender of Detroit by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Tecumseh's Confederacy | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Tecumseh | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

582 regulars 1,600+ militia 30 guns[1] |

600 Natives 330 regulars 400 militia 5 light guns 3 heavy guns, 2 mortars 2 warships[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7 killed 2,493 captured | 2 wounded | ||||||

The Siege of Detroit, also known as the Surrender of Detroit, or the Battle of Fort Detroit, was an early engagement in the Anglo-American War of 1812. A British force under Major General Isaac Brock with Native American allies under the Shawnee leader, Tecumseh, used bluff and deception to intimidate the American Brigadier General William Hull into surrendering the fort and town of Detroit, Michigan, and a dispirited army which nevertheless outnumbered the victorious British and Native Americans.

The British victory reinvigorated the militia and civil authorities of Upper Canada, who had previously been pessimistic and affected by pro-American agitators. Many Native American people in the Northwest Territory were inspired to take arms against American outposts and settlers. The British held Detroit for more than a year before their small fleet on Lake Erie was defeated, which forced them to abandon the western frontier of Upper Canada.

Background

American plans and moves

In the early months of 1812, as tension with Britain increased, President of the United States James Madison and Secretary of War William Eustis were urged by many people, including William Hull, Governor of the Michigan Territory, to form an army which would secure the former Northwest Territory against Native Americans incited to take arms against the United States by British agents and fur trading companies. In particular it was urgently necessary to reinforce the outpost of Detroit, which had a population of 800 but a peacetime garrison of only 120 soldiers.[3] It was also suggested that this army might invade the western districts of Upper Canada, where support might be expected from the many recent immigrants from the United States who had been attracted by generous land grants.[4]

Madison and Eustis concurred with this plan. Madison offered command of the army to Hull, an ageing veteran of the American Revolutionary War. Hull was initially reluctant to take the appointment, but no other officer with his prestige and experience was immediately available. After repeated pleas from Madison, Hull finally accepted, and was commissioned as a Brigadier General in the United States Army.[5]

Hull's army consisted initially of three regiments of Ohio militia under Colonels Lewis Cass, Duncan McArthur and James Findlay. When Hull took command of them at Dayton on 25 May, he found that they were badly equipped and ill-disciplined, and no arrangements had been made to supply them on the march. He made hasty efforts to remedy the deficiencies in equipment. Joined by the 4th U.S. Infantry under Lieutenant Colonel James Miller, the army marched north from Urbana on 10 June. On instructions from Eustis, Hull ignored an earlier route established by Anthony Wayne, and created a new route to Detroit across the Black Swamp area of northwest Ohio.[6] On 26 June, he received a letter from Eustis, dated 18 June, warning him that war was imminent and urging that he should make for Detroit "with all possible expedition".[7] Hull accordingly hastened his march. To lighten the load on his draught horses, worn out by the arduous march, he put his entrenching tools, medical supplies, officers' baggage and despatches, with some sick men and the army's band, aboard the packet vessel Cayahoga at the foot of the Maumee River, to be transported across Lake Erie.

Eustis had sent his first letter of 18 June by special messenger. Congress had passed the declaration of war later that day but Eustis sent a second letter to Hull with this vital information only by ordinary mail.[8] On 28 June, the postmaster at Cleveland, Ohio hired an express rider to rush the letter to Hull but even this arrived only on 2 July. The British ambassador in Washington had sent the news of the American declaration of war urgently to Britain and Canada and the military commanders in Canada had in turn hastened to inform all their outposts of the state of war. On 2 July, the unsuspecting Cayahoga was captured by a Canadian-manned armed brig of the Provincial Marine, the General Hunter, near the British post at Amherstburg at the foot of the Detroit River.[7]

Hull reached Detroit on 5 July. Here he was reinforced by detachments of Michigan militia, including the 140 men of the Michigan Legionary Corps which Hull had established in 1805. The American army was short of supplies, especially food, as Detroit apparently provided only soap and whiskey.[8] Nevertheless, Eustis urged Hull to attack Amherstburg. The fort there was defended by 300 British regulars, mainly from the 41st Regiment of Foot, 400 Native Americans, and some militia.[9] The post's commander was Colonel St. George, who was later superseded by Colonel Henry Procter of the 41st. Although Hull was not enthusiastic, writing to Eustis that "The British command the water and the savages",[10] his army crossed into Canada on 12 July. He issued several proclamations which were intended to induce Canadians to join or support his army. Some of his mounted troops raided up the Thames as far as Moraviantown. Although these moves discouraged many of the militia from opposing Hull's invasion, few of the inhabitants of the region, even those who had recently moved from the United States, actively aided Hull.

After some indecisive skirmishes with British outposts along the Canard River, Hull decided he could not attack the British fort without artillery, which could not be brought forward because the carriages had decayed and needed repair, and he fell back.[11] Several of Hull's officers disagreed with this retreat and secretly discussed removing him from command. Hull had been quarreling with his militia Colonels since taking over the army, and he felt that he did not have their support, whether in the field or in the frequent councils of war he called.

British moves

On 17 July, a mixed force of British regulars, Canadian fur traders and Native Americans captured the important trading post of Mackinac Island on Lake Huron from its small American garrison who, like Hull earlier, were not aware that war had broken out. While many of the Natives who had taken part in the attack either remained at Mackinac or returned to their homes, at least one hundred Sioux, Menominee and Winnebago warriors began moving south from Mackinac to join those already at Amherstburg, while the news induced the previously neutral Wyandots living near Detroit to become increasingly hostile to the Americans. Hull learned of the capture of Mackinac on 3 August, when the paroled American garrison reached Detroit by schooner.[12] Fearing that this had "opened the northern hive of Indians",[13] Hull abandoned all the Canadian territory he held.

Hull's supply lines ran for 60 miles (97 km) along the Detroit River and the shore of Lake Erie, which was dominated by the British armed vessels, and were vulnerable to British and Native American raiders. On 4 August, at the Battle of Brownstown, a party under Tecumseh ambushed and routed an American detachment under Major van Horne, capturing more of Hull's despatches. Hull sent a larger party under James Miller to clear his lines of communication, and escort a supply convoy of 300 head of cattle and 70 pack horses loaded with flour, which was waiting at Frenchtown under Major Brush.[14] On 9 August, at the Battle of Maguaga, Miller forced a British and Indian force under Major Adam Muir of the 41st Regiment to retreat some distance, but when the British re-formed their line, he declined to resume the attack. Miller, who was ill and whose losses in the engagement were heavier than those of the enemy, seemed to completely lose confidence and remained encamped near the battlefield until Hull ordered him to return to Detroit.

Meanwhile, Major General Isaac Brock, the British commander in Upper Canada, was in York, the provincial capital, dealing with the unwilling Assembly and mobilising the province's militia. Although he had only a single regiment of regulars and some small detachments of veterans and artillery to support the militia, he was already aware that there was no immediate threat from the disorganised and badly-supplied American forces on the Niagara River, or from the lethargic American commander in chief, Major General Henry Dearborn, at Albany in Upper New York State. Only Hull's army was occupying or threatening Canadian territory. Late in July, Brock learned of the capture of Mackinac. He was also informed by Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost, the Governor General of Canada, that an additional regiment he had asked for was being dispatched to Upper Canada, although as piecemeal detachments. Brock dispatched 50 of his small force of regulars and 250 volunteers from the militia westward from York to reinforce Amherstburg. On 5 August, he prorogued the Assembly and set out himself after them. He and his force sailed from Port Dover in batteaux and open boats and reached Amherstburg on 13 August,[15] at the same time as 200 additional Native American warriors (100 "Western Indians" from Mackinac and 100 Wyandots) who joined Tecumseh.

At Amherstburg, Brock immediately learned from Hull's captured despatches that the morale of Hull and his army was low, that they feared the numbers of Indians which might be facing them, and that they were short of supplies. Brock also quickly established a rapport with Tecumseh, ensuring that the Indians would cooperate with his moves. Brock and Tecumseh met for the first and only time shortly after Brock arrived at Amherstburg. Legend has it that Tecumseh turned to his warriors and said, "Here is a man!" Brock certainly wrote shortly afterwards, "... a more sagacious and a more gallant Warrior does not I believe exist."[16]

Against the advice of most of his subordinates, Brock determined on an immediate attack on Detroit. The British had already played on Hull's fear of the Natives by arranging for a misleading letter to fall into American hands. The letter asked that no more Indians be allowed to proceed from Fort Mackinac as there were already no less than 5,000 at Amherstburg and supplies were running short. Brock sent a demand for surrender to Hull, stating:

The force at my disposal authorizes me to require of you the immediate surrender of Fort Detroit. It is far from my intention to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware, that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences…

To deceive the Americans into believing there were more British troops than there actually were, Brock's force carried out several bluffs. At the suggestion of Major Thomas Evans, the Brigade Major at Fort George, Brock gave his militia the cast-off uniforms of the 41st Regiment to make Hull believe most of the British force were regulars.[17] The troops were told to light individual fires instead of one fire per unit, thereby creating the illusion of a much larger army. They marched to take up positions in plain sight of the Americans then quickly ducked behind entrenchments, and marched back out of sight to repeat the manoeuvre. The same trick was carried out during meals, where the line would dump their beans into a hidden pot, then return out of view to rejoin the end of the queue.

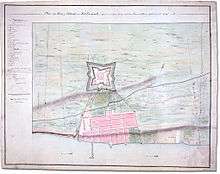

Battle

On 15 August, gunners of the Provincial Marine set up a battery of one 18-pounder and two 12-pounder guns and two mortars on the Canadian shore of the Detroit River and began bombarding Fort Detroit, joined by two armed vessels (the General Hunter and the 20-gun sloop-of-war Queen Charlotte in the river. In the early hours of the morning of 16 August, Tecumseh's warriors crossed the river about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Detroit.[18] They were followed after daybreak by Brock's force, divided into three small "brigades". The first was composed of 50 men of the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles and some Lincoln and Kent militia; the second consisted of 50 men of the 41st Regiment with York, Lincoln, Oxford and Norfolk militia; the third was formed from the main body of the 41st (200 men) and 50 men of the Royal Artillery with five field guns (three 6-pounders and two 3-pounders).[2]

Brock originally intended to occupy a fortified position astride Hull's supply line and wait for starvation and bombardment to force the Americans to surrender or come out to fight, but he then learned that on the previous day, Hull had sent a detachment of 400 men under Colonels Cass and McArthur to escort Brush's convoy to Detroit via a backwoods trail some distance from the lake and river,[19] and this detachment was only a few miles from the British rear. (Hull had sent messengers recalling this force the night before, but Cass and MacArthur had already encamped for the night and declined to move.) To avoid being caught between two fires, Brock advanced immediately against the rear of Fort Detroit, the side furthest from the river where the defences were weakest.[18] Tecumseh's warriors meanwhile paraded several times past a gap in the forests where the Americans could see them, while making loud war cries. One account claims that Tecumseh was behind the idea of displaying trumped-up troop levels. A Canadian officer (militia cavalry leader William Hamilton Merritt) noted that "Tecumseh extended his men, and marched them three times through an opening in the woods at the rear of the fort in full view of the garrison, which induced them to believe there were at least two or three thousand Indians."[20] Because Merritt was not an eyewitness, his version has been disputed.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

As the British prepared to attack, a shell exploded in the officers' mess inside the fort, causing casualties. Hull despaired of holding out against a force which seemingly consisted of thousands of British regulars and, hearing the Indian war cries, began to fear a slaughter. Women and children, including his own daughter and grandchild, still resided within the fort. Against the advice of his subordinates, Hull hoisted a white flag of surrender. He sent messengers to Brock asking for three days to agree on terms of surrender. Brock replied he would allow him three hours. Hull surrendered his entire force, including Cass's and McArthur's detachment and Major Brush's supply convoy. There were rumours that General Hull had been drinking heavily prior to the surrender. He is reported to have said the Indians were "numerous beyond example," and "more greedy of violence… than the Vikings or Huns."[21]

Casualties and losses

Before the surrender, the British bombardment had killed two American officers (including Lieutenant Porter Hanks, the former commander of Fort Mackinac, who was awaiting a court martial), and five other ranks. The answering fire from the guns of Fort Detroit wounded two British gunners.

After Hull surrendered, the 1,600 Ohio militia from his army were paroled and were escorted south until they were out of danger of attack from the natives. Most of the Michigan militia had already deserted. The 582 American regulars were sent as prisoners to Quebec City.

Among the booty and military stores surrendered were 33 cannon,[22] 300 rifles and 2,500 muskets. The only armed American vessel on the Upper Lakes, the brig Adams, was captured and taken into British service, but was recaptured a few weeks later near Fort Erie, and later ran aground and was set on fire.

Aftermath

British

The news of the surrender of Hull's army was startling on both sides of the border. On the American side, many Indians took up arms and attacked American settlements and isolated military outposts.[23] In Upper Canada, the population and militia were encouraged, particularly in the Western districts where they had been threatened by Hull's army. Brock overlooked the local militia's former reluctance to perform their duty, instead rewarding those militiamen who had remained at their posts. More materially, the 2,500 muskets captured from Hull were distributed among the hitherto ill-equipped militia.

The British gained an important post on American territory and won control over Michigan Territory and the Detroit region for most of the following year. Brock was hailed as a hero, and Tecumseh's influence over the confederation of natives was strengthened. Brock next intended to mount a pre-emptive attack into New York State to forestall an American attack across the Niagara River. He was thwarted by an armistice arranged by Sir George Prevost. When this ended, the Americans attacked in October near Queenston. At the ensuing Battle of Queenston Heights, Brock was killed leading a hasty counter-attack to recover a battery which had been captured by the Americans. Under Brock's successor, Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, the British drove the Americans from their positions on the heights, and captured several hundred American soldiers. Nevertheless, the loss of Brock is generally reckoned to have been a severe blow to the British.

Americans

A third American invasion of Canada took place in November, north of Lake Champlain. After the Americans accidentally fired on each other in the dark, they gave up and retreated after a brief engagement at Lacolle Mills. "The whole Canadian campaign had produced nothing but 'disaster, defeat, disgrace, and ruin and death'" the Green-Mountain Farmer, a Vermont newspaper, reported in January 1813.

General Hull was tried by court martial and was sentenced to death for his conduct at Detroit, but the sentence was commuted by President Madison to dismissal from the Army, in recognition of his honourable service in the American Revolution.

American attempts to regain Detroit were continually thwarted by poor communications and the difficulties of maintaining militia contingents in the field, until the Americans won a naval victory at the Battle of Lake Erie on 10 September 1813. This isolated the British at Amherstburg and Detroit from their supplies and forced them to retreat. Hull's successor, Major General William Henry Harrison, pursued the retreating British and their native allies and defeated them at the Battle of the Thames, where Tecumseh was killed.

Memorials

The British 41st Regiment, which subsequently became the Welch Regiment, was awarded the battle honour "Detroit", one of the few to be awarded to British regiments for the War of 1812. The captured colours of the 4th U.S. Infantry are currently in the Welch Regiment Museum at Cardiff Castle.

A patriotic song "The Bold Canadian" was written by a private on the campaign to commemorate the conquering of Detroit in Michigan Territory. Link to song

Six currently active regular battalions of the United States Army (5-3 FA, 1-3 Inf, 2-3 Inf, 4-3 Inf, 1-5 Inf and 2-5 Inf) perpetuate the lineages of several American units (Freeman's Company, 1st Regiment of Artillery, and the old 1st, 4th and 19th Infantry Regiments) that participated in Hull's initial invasion of Canada and his subsequent surrender of Detroit.

Six infantry/armoured regiments of the Canadian Army carry the battle honour Detroit to commemorate the service of ancestor units in the campaign. They are: the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Queen's York Rangers, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Essex and Kent Scottish Regiment the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, and The Lorne Scots. The 56th Field Artillery Regiment, RCA is also recognized for its links to the battle. In 2012, the Royal Canadian Mint released a 25¢ coin depicting Tecumseh to mark the War of 1812's bicentennial.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Hitsman, p.81

- 1 2 Hitsman, pp.79-80

- ↑ Elting, p. 24

- ↑ Elting, p. 25

- ↑ Elting, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Elting, pp. 24-26

- 1 2 Elting, p. 26

- 1 2 Elting, p. 27

- ↑ Elting, p. 28

- ↑ Hitsman, p. 70

- ↑ Hitsman, pp. 71-72

- ↑ Hitsman, p.75

- ↑ C. P. Stacey, The Defence of Upper Canada, 1812, in Zaslow (ed), p.18

- ↑ Elting, p.30

- ↑ C. P. Stacey, The Defence of Upper Canada, 1812, in Zaslow (ed), p.17

- ↑ Hitsman, p.78

- ↑ Cruikshank, p.186

- 1 2 Elting, pp.34-35

- ↑ Elting (1995), p.32

- ↑ Merritt, in Wood, William ed. Select British Documents of the Canadian War of 1812. British documents, 3:554.)

- ↑ Gilbert, Bil (1989). God Gave us This Country: Tekamthi and the First American Civil War. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-11632-2.

- ↑ Porter (1889), p.357

- ↑ Elting, pp.36-37

Bibliography

- Elting, John R. (1995). Amateurs to Arms. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay (1999). The Incredible War of 1812. Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- Hull, William (1824). Memoirs of the Campaign of the Northwestern Army of the United States, A.D. 1812. True & Greene.

- Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02584-9.

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- Zaslow, Morris (1964). The Defended Border. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 0-7705-1242-9.

External links

- Cruikshank, Ernest A. "The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier. Part 3". Lundy's Lane Historical Society. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- PBS Documentary on the War of 1812 features a chapter on Detroit.