Burning of Washington

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

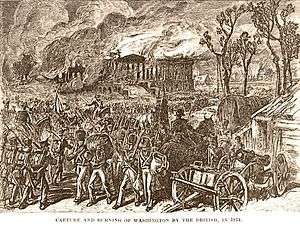

The Burning of Washington was a British attack against Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, during the War of 1812. On August 24, 1814, after defeating the Americans at the Battle of Bladensburg, a British force led by Major General Robert Ross occupied Washington and set fire to many public buildings, including the White House (known as the Presidential Mansion at the time) and the Capitol, as well as other facilities of the U.S. government.[2] The attack was in part a retaliation for the recent American destruction of Port Dover in Upper Canada. It marks the only time in U.S. history that Washington, D.C. has been occupied by a foreign force.

President James Madison, military officials, and his government fled the city in the wake of the British victory at the Battle of Bladensburg. They eventually found refuge for the night in Brookeville, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland, which is known today as the "United States Capital for a Day." President Madison spent the night in the house of Caleb Bentley, a Quaker who lived and worked in Brookeville. Bentley's house, known today as the Madison House, still stands in Brookeville.

Less than a day after the attack began, a sudden, very heavy thunderstorm—possibly a hurricane—put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that passed through the center of the capital, setting down on Constitution Avenue and lifting two cannons before dropping them several yards away, killing British troops and American civilians alike. Following the storm, the British returned to their ships, many of which were badly damaged. The occupation of Washington lasted only about 26 hours. After the "Storm that saved Washington", as it soon came to be called, the Americans were able to regain control of the city.[3]

Reasons for the attack

The British government, absorbed in a life-or-death struggle with Napoleonic France, adopted a defensive strategy against the United States when the Americans declared war in 1812. Reinforcements were held back from Canada and reliance was instead made on local militias and native allies to bolster the British Army in Canada. However, after the defeat and exile of Napoleon Bonaparte in April 1814, Britain was able to use its now available troops and ships to prosecute its war with the United States. In addition to reinforcements sent to Canada, the Earl of Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, dispatched an army brigade and additional naval vessels to Bermuda, from where a blockade of the US coast and even the occupation of some coastal islands had been overseen throughout the war. It was decided to use these forces in raids along the Atlantic seaboard to draw American forces away from Canada.[4] The commanders were under strict orders, however, not to carry out operations far inland, or to attempt to hold territory. Early in 1814, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy's North America and West Indies Station, controlling naval forces based at the new Bermuda dockyard and the Halifax Naval Yard which were used to blockade US Atlantic ports throughout the war. He planned to carry the war into the United States by attacks in Virginia and against New Orleans.[5]

Rear Admiral George Cockburn had commanded the squadron in Chesapeake Bay since the previous year. On June 25 he wrote to Cochrane, stressing that the defenses there were weak, and he felt that several major cities were vulnerable to attack.[6] Cochrane suggested attacking Baltimore, Washington and Philadelphia. On July 17, Cockburn recommended Washington as the target, because of the comparative ease of attacking the national capital and "the greater political effect likely to result".[7]

An added motive was retaliation for what Britain saw as the "wanton destruction of private property along the north shores of Lake Erie" by American forces under Col. John Campbell in May 1814, the most notable being the Raid on Port Dover.[8] On June 2, 1814, Sir George Prévost, Governor General of The Canadas, wrote to Cochrane at Admiralty House, in Bailey's Bay, Bermuda, calling for a retaliation against the American destruction of private property in violation of the laws of war. Prévost argued that,

… in consequence of the late disgraceful conduct of the American troops in the wanton destruction of private property on the north shores of Lake Erie, in order that if the war with the United States continues you may, should you judge it advisable, assist in inflicting that measure of retaliation which shall deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages.[8]

On July 18, Cochrane ordered Cockburn that to "deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages....You are hereby required and directed to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts as you may find assailable".[9] Cochrane instructed, "You will spare merely the lives of the unarmed inhabitants of the United States". Ross and Cockburn surveyed the torching of the President's Mansion, during which time a great storm arose unexpectedly out of the southeast. They were confronted a number of times while on horseback by older women from around Washington City and elderly clergymen (Southern Presbyterian and Southern Baptist), with women and children who had been hiding in homes and churches. They requested protection from abuse and robbery by enlisted personnel from the British Expeditionary Forces whom they accused of having tried to ransack private homes and other buildings. Major-General Ross had two British soldiers put in chains for violation of his general order. Throughout the events of that day, a severe storm blew into the city, worsening on the night of August 24, 1814.

Events

President James Madison, members of his government, and the military fled the city in the wake of the British victory at the Battle of Bladensburg. They eventually found refuge for the night in Brookeville, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland, which is known today as the United States Capital for a Day. President Madison spent the night in the house of Caleb Bentley, a Quaker who lived and worked in Brookeville. Bentley's house, known today as the Madison House, still stands in Brookeville.[10]

The sappers and miners of the Corps of Royal Engineers under Captain Blanshard were employed in burning the principal buildings. Blanshard reported that it seemed that the American President was so sure that the attacking force would be made prisoners that a handsome entertainment had been prepared. Blanshard and his sappers enjoyed the feast.[11]:358

U.S. Capitol

The Capitol was, according to some contemporary travelers, the only building in Washington "worthy to be noticed."[12] Thus, it was a prime target for the invaders, both for its aesthetic and symbolic value. After looting the building, the British found it difficult to set the structure on fire, owing to its sturdy stone construction. Soldiers eventually gathered furniture into a heap and ignited it with rocket powder, which successfully set the building ablaze. Among the casualties of the destruction of the Capitol was the Library of Congress, the entire 3,000 volume collection of which was destroyed.[13] Several surrounding buildings in Capitol Heights also caught fire. After the war, Thomas Jefferson sold his own personal library to the government in order to pay personal debts, re-establishing the Library of Congress.

White House

After burning the Capitol, the troops turned northwest up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. After US government officials and President Madison fled the city, the First Lady Dolley Madison received a letter from her husband, urging her to be prepared to leave Washington at a moment's notice.[14] Dolley organized the slaves and staff to save valuables from the British.[15] James Madison's personal slave, the fifteen-year-old boy Paul Jennings, was an eyewitness.[16] After later buying his freedom from the widow Dolley Madison, Jennings published his memoir in 1865, considered the first from the White House:

It has often been stated in print, that when Mrs. Madison escaped from the White House, she cut out from the frame the large portrait of Washington (now in one of the parlors there), and carried it off. She had no time for doing it. It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were thought to be but a few squares off, and were expected any moment.[17]

Jennings said the people who saved the painting and removed the objects actually were:

John Susé (Jean Pierre Sioussat) (a Frenchman, then door-keeper, and still living) and Magraw [McGraw], the President's gardener, took it down and sent it off on a wagon, with some large silver urns and such other valuables as could be hastily got hold of. When the British did arrive, they ate up the very dinner, and drank the wines, &c., that I had prepared for the President's party.[17][18][19]

The soldiers burned the president's house, and fuel was added to the fires that night to ensure they would continue burning into the next day.

In 2009, President Barack Obama held a ceremony at the White House to honor Jennings as a representative of his contributions to saving the Gilbert Stuart painting and other valuables. [According to recorded history of this event, the painting that was saved was a copy of the Gilbert Stuart painting, NOT the original][20] "A dozen descendants of Jennings came to Washington, to visit the White House. They looked at the painting their relative helped save."[21] In an interview with National Public Radio, Jennings' great-great-grandson Hugh Alexander said, "We were able to take a family portrait in front of the painting, which was for me one of the high points."[16] He confirmed that Jennings later purchased his freedom from the widowed Dolley Madison.[16]

Other Washington properties

%2C_by_John_James_Halls.jpg)

_(Harper's_engraving).png)

The day after the destruction of the White House, Rear Admiral Cockburn entered the building of the D.C. newspaper, the National Intelligencer, intending to burn it down. However, several women persuaded him not to because they were afraid the fire would spread to their neighboring houses. Cockburn wanted to destroy the newspaper because its reporters had written so negatively about him, branding him as "The Ruffian." Instead, he ordered his troops to tear the building down brick by brick, ordering all the "C" type destroyed "so that the rascals can have no further means of abusing my name."[22]

The British sought out the United States Treasury in hopes of finding money or items of worth, but the British Army only found old records.[23] The British burned the United States Treasury and other public buildings. The United States Department of War building was also burned. However, the War and State Department files had been removed thus all books and records had been saved; the only records of the War Department lost were recommendations of appointments for the Army and letters received from seven years previous.[24] The First U.S. Patent Office Building was saved by the efforts of William Thornton, the former Architect of the Capitol and then the Superintendent of Patents, who gained British cooperation to preserve it.[25][upper-alpha 1] "When the smoke cleared from the dreadful attack, the Patent Office was the only Government building . . . left untouched" in Washington.[26]

The Americans had already burned much of the historic Washington Navy Yard, founded by Thomas Jefferson, to prevent capture of stores and ammunition,[27] as well as the 44-gun frigate USS Columbia and the 18 gun USS Argus both new vessels nearing completion.[28] The Navy Yard's Latrobe Gate, Quarters A, and Quarters B were the only buildings to escape destruction.[29][30] Also spared were the Marine Barracks and Commandant's House, although several private properties were damaged or destroyed.[31]

In the afternoon of August 25, General Ross sent two hundred men to secure a fort on Greenleaf's Point. The fort, later known as Fort McNair, had already been destroyed by the Americans, but 150 barrels of gunpowder remained. While the British were trying to destroy it by dropping the barrels into a well, the powder ignited. As many as thirty men were killed in the explosion, and many others were maimed.[32]

"The Storm that Saved Washington"

Less than a day after the attack began, a sudden very heavy thunderstorm—possibly a hurricane—put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that passed through the center of the capital, setting down on Constitution Avenue[3] lifting two cannons before dropping them several yards away and killing British troops and American civilians alike.[33] Following the storm, the British troops returned to their ships, many of which were badly damaged. There is some debate regarding the effect of this storm on the occupation. While some assert that the storm forced their retreat,[3] it seems likely from their destructive and arsonous actions before the storm, and their written orders from Cochrane to "destroy and lay waste",[34] that their intention was merely to raze the city, rather than occupy it for an extended period. Whatever the case, the British occupation of Washington lasted only about 26 hours. Despite this, the "Storm that saved Washington" as it became known, did the opposite according to some. The rains sizzled and cracked the already charred walls of the White House and ripped away at structures the British had no plans to destroy (such as the Patent Office). The storm may have exacerbated an already dire situation for Washington DC.

An encounter was noted between Sir George Cockburn 10th Baronet and a female resident of Washington. "Dear God! Is this the weather to which you are accustomed to in this infernal country?" enquired the Admiral. "This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city,” the woman allegedly called out to Cockburn. "Not so, Madam," Cockburn retorted. “It is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city", before riding off on horseback.[35] Yet, the British left right after the storm completely unopposed by any American military forces.

The Royal Navy reported that it lost one man killed and six wounded in the attack, of whom the fatality and three of the wounded were from the Corps of Colonial Marines.[36]

The destruction of the Capitol, including the Senate House and the House of Representatives, the Arsenal, Dockyard, Treasury, War Office, President's mansion, bridge over the Potomac, a frigate and a sloop together with all Materiel was estimated at £365,000.[11]:359

A separate British force captured Alexandria, on the south side of the Potomac River, while Ross's troops were leaving Washington. The mayor of Alexandria made a deal and the British refrained from burning the town.[37]

President Madison returned to Washington by September 1, on which date he issued a proclamation calling on citizens to defend the District of Columbia.[38] Congress returned and assembled in special session on September 19. Due to the destruction of the Capitol and other public buildings, they initially met in the Post and Patent Office building.[39]

Aftermath

Most contemporary American observers, including newspapers representing anti-war Federalists, condemned the destruction of the public buildings as needless vandalism.[40] Many of the British public were shocked by the burning of the Capitol and other buildings at Washington; such actions were denounced by most leaders of continental Europe. According to The Annual Register, the burning had "brought a heavy censure on the British character," with some members of Parliament, including the anti-establishment MP Samuel Whitbread,[40] joining in the criticism.

The majority of British opinion believed that the burnings were justified following the damage that United States forces had done with its incursions into Canada. In addition, they noted that the United States had been the aggressor, declaring war and initiating it.[41] Several commentators regarded the damages as just revenge for the American destruction of the Parliament buildings and other public buildings in York, the provincial capital of Upper Canada, early in 1813. Sir George Prévost wrote that "as a just retribution, the proud capital at Washington has experienced a similar fate."[42] The Reverend John Strachan, who as Rector of York had witnessed the American acts there, wrote to Thomas Jefferson that the damage to Washington "was a small retaliation after redress had been refused for burnings and depredations, not only of public but private property, committed by them in Canada."[43]

When they ultimately returned to Bermuda, the British forces took two pairs of portraits of King George III and his wife, Queen Charlotte, which had been discovered in one of the public buildings. One pair currently hangs in the House of Assembly of the Parliament of Bermuda, and the other in the Cabinet Building, both in the city of Hamilton.[44]

Reconstruction

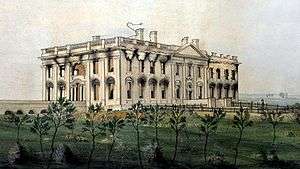

The thick sandstone walls of the White House and Capitol survived, although scarred with smoke and scorch marks. There was a strong movement in Congress to relocate the nation's capital with many northern Congressmen pushing for a city north of the Mason–Dixon line. Philadelphia was quick to volunteer as a temporary home as did Georgetown, where Mayor Thomas Corcoran offered Georgetown College as a temporary home for Congress. Ultimately, a bill to relocate the capital was defeated in Congress and Washington remained the seat of government.

Fearful that there might be pressure to relocate the capital altogether, Washington businessmen financed the construction of the Old Brick Capitol, where Congress met while the Capitol was reconstructed from 1815 to 1819. Madison resided in The Octagon House for the remainder of his term. Reconstruction of the White House began in early 1815 and was finished in time for President James Monroe's inauguration in 1817.[45]

See also

Bibliography

Footnotes

- ↑ Brief History of the United States Patent Office from its foundation—1790 to 1886—with an outline of laws, growth, publications, office routine, etc. Washington, D.C.: R. Beresford, Printer. 1886. Retrieved December 16, 2011. It is written that a loaded cannon was aimed at the Patent Office to destroy it. Thornton "put himself before the gun, and in a frenzy of excitement exclaimed: 'Are you Englishmen or only Goths and Vandals? This is the Patent Office, a depository of the ingenuity of the American nation, in which the whole civilized world is interested. Would you destroy it? If so, fire away, and let the charge pass through my body.' The effect is said to have been magical upon the soldiers, and to have saved the Patent Office from destruction."

Endnotes

- ↑ "Burning of Washington, D.C.;Chesapeake Campaign". The War of 1812. genealogy, Inc. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ↑ "The White House at War: The White House Burns: The War of 1812". White House Historical Association. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- 1 2 3 The War of 1812, Scene 5 'An Act of Nature', History Channel, 2005

- ↑ Hitsman & Graves 1999, p. 240.

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 100.

- ↑ Morriss 1997, p. 101.

- 1 2 Cruikshank 2006, p. 402.

- ↑ Cruikshank 2006, p. 414.

- ↑ "Brookeville 1814". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- 1 2 Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ Herrick 2005, p. 92.

- ↑ Herrick 2005, p. 96.

- ↑ Pitch, Anthony S. (1998). The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Willets includes Dolley Madison's letter to her sister describing these events. (Willets 1908, p. 219)

- 1 2 3 Siegel & Block 2009, Descendant...

- 1 2 Jennings 1865, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Corrected spelling of names of staff comes from Willets (Willets 1908, p. 221)

- ↑ Sioussat was the first Master of Ceremonies of the White House (McCormick 1904, p. 170).

- ↑ http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/british-troops-set-fire-to-the-white-house

- ↑ Gura 2009, Descendants of a slave....

- ↑ Fredriksen 2001, p. 116.

- ↑ Herrick 2005, p. 99.

- ↑ Business Methods in the War Department: Report of the Board Appointed in Compliance with the Request of the Senate Select Committee to Investigate the Methods of Business in the Executive Departments. By United States. War Dept. Board on Business Methods 1889 .p.184

- ↑ "The Patent Fire of 1836". patentlaws.com. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ↑ "One Hot Commodity: Great Patent Fire of 1836 United States Patent Office". Kids pages. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ↑ Crawford, p222, quoting letter from Cockburn to Cochrane dated August 27, 1814 'The Enemy himself, on our entering the Town set fire to …'

- ↑ "It is one of the few structures to have escaped the fire in 1814 when the British invaded Washington." (Gerson & Branam 1973, p. 5)

- ↑ "When the British captured Washington on August 24, 1814, and Captain Tingey ordered the Navy Yard set fire to prevent the British using the Yard and its ships to their advantage, both Quarters A (Tingey's House) and Quarters B (Lieutenant Haraden's House) were untouched, but the people the neighborhood plundered them to such an extent that 'not a movable object from cellar to garret was left, and even the fixtures and locks off the doors were taken." (Taylor 1973, p. 3,5)

- ↑ "Act of July 14, 1832, to pay estate of Edward Barry $568.35 for property destroyed in the burning of the Washington navy-hard by the British in 1814 ... Act of March 2, 1833, to pay the estate of George Hodge $824.18 for property destroyed in the burning of the Washington navy-yard by the British in 1814." (Reports... 1894, p. 174)

- ↑ George 2000, p. 111.

- ↑ NWS staff 2011.

- ↑ Cruikshank 2006, p. 414.

- ↑ Peter Snow "When Britain Burned the White House" 2012

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16939. pp. 1942–1943. September 27, 1814. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ↑ Landry 2009, p. 255.

- ↑ "James Madison, Proclamation – Calling All Citizens to Unite in Defense of the District of Columbia September 1, 1814". The American Presidency Project.

- ↑ Howe, David Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 67.

- 1 2 Hitsman & Graves 1999, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Hickey 1989, p. 202.

- ↑ Elting 1995, p. 220.

- ↑ Hitsman & Graves 1999, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ POTSI (archived): HM Queen Elizabeth addresses the colonial Parliament in 1976

- ↑ Hickey 1989, p. 11.

References

- Crawford, Michael J. (Ed) (2002). The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, Vol. 3. Washington: United States Department of Defense. ISBN 978-0-16-051224-7

- Cruikshank, Ernest (2006) [1814]. The Documentary History of the campaign upon the Niagara frontier. (Part 1-2). University of Calgary. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- Elting, John R. (1995). Amateurs to Arms! A Military History of the War of 1812. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- Fredriksen, John C. (2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-57607-603-3.

- George, Christopher T (2000). Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay. White Mane Books. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-57249-276-9.

- Gerson, Leonard; Branam, Alfred (August 14, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- Gleig, George Robert (1827). The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, 1814–1815. London: J. Murray. ISBN 0-665-45385-X.

- Gura, David (August 24, 2009). "Descendants of a Slave See The Painting He Saved". The Two-Way. NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- Herrick, Carole (2005). August 24, 1814: Washington in Flames. Falls Church, VA: Higher Education Publications, Inc.

- Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812, A Forgotten Conflict. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, Chicago and Urbana. ISBN 0-252-01613-0.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay; Graves, Donald E. (1999). The Incredible War of 1812. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- Jennings, Paul (1865). A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison. Brookyn: George C. Beadle.

- Landry, Peter (2009). Settlement, Revolution & War. Bloomington, IL: Trafford Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4251-8791-0.

- McCormick, John H. (1904). "The First Master of Ceremonies of the White House". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. Washington, D.C. 7: 170–194. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- Morriss, Roger (1997). Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 1772–1853. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-253-0.

- NWS staff (June 15, 2011). "NWS Sterling, VA – D.C. Tornado Events". National Weather Service Eastern Region Headquarters. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- Myatt, Kevin (August 26, 2006). "Did tornado wreak havoc on War of 1812?". The Roanoke Times. Roanoke, VA. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1902). The Naval War of 1812 or the History of the United States Navy during the Last War with Great Britain to Which Is Appended an Account of the Battle of New Orleans. Part II. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Siegel, Robert; Block, Melissa (August 24, 2009). "Descendant Of White House Slave Shares Legacy". NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- Taylor, Nancy (August 14, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- The Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-Third Congress. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1894. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- Willets, Gilson (1908). Inside History of the White House-the complete history of the domestic and official life in Washington of the nation's presidents and their families. New York: The Christian Herald.

Further reading

- Latimer, Jon. 1812: War with America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-674-02584-9

- Martin, John. "The British Are Coming: Historian Anthony Pitch Describes Washington Ablaze," LC Information Bulletin, September 1998

- Pack, A. James. The Man Who Burned The White House, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87021-420-9

- Phelan, Mary Kay. The Burning of Washington: August 1814, Ty Crowell Co, 1975. ISBN 0-690-00486-9

- Pitch, Anthony S. The Burning of Washington, White House History Magazine, Fall 1998

- Pitch, Anthony S. The Burning of Washington, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55750-425-3

- Siegel, Robert Descendant Of White House Slave Shares Legacy NPR, August 24, 2009.

- Snow, Peter "When Britain Burned the White House, The 1814 Invasion of Washington", London: John Murray, 2013. ISBN 978-1-250-04828-8

- Whitehorne, Joseph A. The Battle for Baltimore: 1814 (1997)

- Listing by surname of Royal Marines (2nd Battn, 3rd Battn, Colonial Marines) paid prize money for participating in the attack on Washington

External links

- The War of 1812 and Relocating the Nation's Capital

- Brookeville 1814, U.S. Capital for a Day Maryland State Archives