Battle of North Point

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

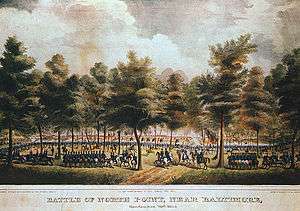

The Battle of North Point was an engagement in the War of 1812, fought on September 12, 1814, between Brigadier General John Stricker's Third Brigade of the Maryland State Militia and a British landing force, composed of units from the British Army, Royal Navy seamen and Royal Marines, and led by Major General Robert Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn. The events and result of the engagement, a part of the larger Battle of Baltimore, saw the U.S. forces retreating after having inflicted heavy casualties on the British.[7]

One of the casualties was Ross, killed during the course of the battle by American sharpshooters. His death significantly demoralized the troops under his command and left some units confused and lost among the woods and marshes of Patapsco Neck. This prompted the British second-in-command, Colonel Arthur Brooke of the 44th Regiment of Foot, to have his troops remain on the battlefield for the evening and night, treating the wounded at the nearby Methodist meeting house, thus delaying his advance against Baltimore.

This delay gave the Americans more time to organize the defense of the city, under the command of Major General Samuel Smith, along an extensive network of trenches and fortifications, with a central strong point of "Rodgers' Bastion", commanded by U.S. Navy Commodore John Rodgers. Stricker slowly retreated back to the main defenses, cutting down trees across the roads to delay the British advance, and rejoined the existing regular, militia and civilian forces of approximately 15,000 men and 100 cannons. Along with the failure of the Royal Navy to neutralize Fort McHenry guarding Baltimore Harbor, the resulting vast numerical superiority over the British force of 4,000 men and 4 cannons led to the subsequent abandonment of the planned assault on Baltimore.

Background

British movements

Major General Robert Ross had been dispatched to Chesapeake Bay with a brigade of veterans from the Duke of Wellington's army from the Spanish Peninsular Wars early in 1814, reinforced with a battalion of Royal Marines and seamen from the Royal Navy under Rear Admiral George Cockburn. They had already defeated a hastily assembled force of Maryland, Baltimore and District of Columbia state militia at the Battle of Bladensburg, northeast of Washington, D.C. on August 24, 1814, and burned Washington, the new national capital but rough village. Having disrupted the American government, he withdrew to the waiting ships of the Royal Navy at Benedict, Maryland, withdrawing down the Patuxent River before later heading further up the Chesapeake Bay to the strategically more important port city of Baltimore, although the Americans managed to defeat a British landing at Caulk's Field on the Eastern Shore of the Bay and killing their commander, Captain Sir Peter Parker (1785–1814), before doing so.

Ross's small army of 3,700 troops and 1,000 marines[8] landed at North Point at the end of the peninsula between the Patapsco River and the Back River on the morning of September 12, 1814, and began moving toward the city of Baltimore.[9]

American defenses

Major General Samuel Smith of the Maryland militia anticipated the British move, and dispatched Brigadier General John Stricker's column to meet them. Stricker's force consisted of five regiments of Maryland militia, a small militia cavalry regiment from Maryland, a battalion of three volunteer rifle companies and a battery of six 4-pounder field guns.[11] Stricker deployed his brigade half way between Hampstead Hill, just outside Baltimore, where there were earthworks and artillery emplacements, and North Point. At that point, several tidal creeks narrowed the peninsula to only a mile wide, and it was considered an ideal spot for opposing the British before they reached the main American defensive positions.[9]

Stricker received intelligence that the British were camped at a farm just 3 miles (4.8 km) from his headquarters.[9] He deployed his men between Bear Creek and Bread and Cheese Creek, which offered cover from nearby woods, and had a long wooden fence near the main road. Stricker placed the 5th Maryland Regiment and the 27th Maryland Regiment and his six guns in the front defensive line, with two regiments (the 51st and 39th) in support, and one more (the 6th) in reserve. He placed his men in mutually supporting positions, relying on numerous swamps and the two streams to stop a British flank attack, all of which he hoped would help avoid another disaster such as Bladensburg.[12]

The riflemen initially occupied a position some miles ahead of Stricker's main position, to delay the British advance. However, their commander, Captain William Dyer, hastily withdrew on hearing a rumour that British troops were landing from the Back River behind him, threatening to cut off his retreat. Stricker posted them instead on his right flank.[13]

Battle

Opening skirmish

At about midday on the 12th, Stricker heard the British had halted while the soldiers had a meal, and some sailors attached to Ross's force plundered nearby farms. He decided it would be better to provoke a fight rather than wait for a possible British night attack. At 1:00 pm, he sent Major Richard Heath with 250 men and one cannon to draw the British to Stricker's main force.[12]

Heath advanced down the road and soon began to engage the British pickets. When Ross heard the fighting, he quickly left his meal and ran to the scene.[12] His men attempted to drive out the concealed American riflemen. Rear Admiral George Cockburn, second in command of the Royal Navy's American Station who usually accompanied Ross, was cautious about advancing without more support and Ross agreed that he would leave and bring back the main army.[12] However, Ross never got the chance, as an American rifleman shot him in the chest.[12] Mortally wounded, Ross turned command over to Colonel Arthur Brooke and died soon after.[12]

Main battle

Brooke reorganized the British troops and prepared to assault the American positions at 3:00 pm.[12] He decided to use his three cannon to cover an attempt by his 4th Regiment to get around the American flank, while two more regiments and the naval brigade would assault the American center.[12] The British frontal assault took heavy casualties as the American riflemen fired into the British ranks, and lacking canister the Americans loaded their cannon with broken locks, nails and horseshoes, firing scrap metal at the British advance.[12] Nevertheless, the British 4th Regiment managed to outflank the American positions and sent many of the American regiments fleeing. Stricker was able to conduct an organized retreat, with his men firing volleys as they continued to fall back. This proved effective, killing one of the British commanders and leaving some units lost among woods and swampy creeks, with others in confusion.[12]

Not all the militia regiments performed with equal distinction. The 51st Regiment and some men of the 39th broke and ran under fire. Robert Henry Goldsborough, US Senator and serving as a Major in the militia, reflected his feelings on the conduct of the militia units and the battle in general a week later, stating that:

The affair at Baltimore was...as little glorious to our arms as that at Bladensburg. Our militia were completely defeated routed.[14]

Goldsborough's account of the battle is distinctly more critical and pessimistic than those of Smith and Stricker, and arguably has a greater basis in reality. For example, Smith initially stated the British had near double the numbers they actually had, which is not the first example of exaggeration on the part of the American commanders involved with the affair at Baltimore.[15] However, the 5th and 27th held their ground and retreated in good order, having inflicted significant casualties on the enemy.[16] Only one American gun was lost.

Corporal John McHenry of the 5th Regiment wrote of the battle:

Our Regiment, the 5th, carried off the praise from the other regiments engaged, so did the company to which I have the honor to belong cover itself with glory. When compared to the [other] Regiments we were the last that left the ground... had our Regiment not retreated at the time it did we should have been cut off in two minutes.[16]

Brooke did not follow the retreating Americans. He had advanced to within a mile of the main American position, but he had suffered heavier casualties than the Americans. As it was getting dark, he chose to wait until Fort McHenry was expected to be neutralized,[17] while Stricker withdrew to Baltimore's main defences.

Casualties

The official British Army casualty report, signed by Major Henry Debbeig, gives 39 killed and 251 wounded. Of these, 28 killed and 217 wounded belonged to the British Army; 6 killed and 20 wounded belonged to the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Royal Marines; 4 killed and 11 wounded belonged to the contingents of Royal Marines detached from Cockburn's fleet; and 1 killed (Elias Taylor) and 3 wounded belonged to the Royal Marine Artillery.[4] As was normal, the Royal Navy submitted a separate casualty return for the engagement, signed by Rear-Admiral Cockburn, which gives 4 sailors killed and 28 wounded but contradicts the British Army casualty report by giving 3 killed (1 and 2 from HMS Madagascar and HMS Ramillies respectively) and 15 wounded for the Royal Marines detached from the ships of the Naval fleet.[18] A subsequent casualty return from Cochrane to the Admiralty, dated 22 September 1814, gives 6 sailors killed, 1 missing and 32 wounded, with Royal Marines casualties of 1 killed and 16 wounded.[19] The total British losses, as officially reported, were either 43 killed and 279 wounded or 42 killed and 283 wounded, depending on which of the two casualty returns was accurate. Historian Franklin R. Mullaly gives still another version of the British casualties, 46 killed and 295 wounded, despite using these same sources.[20][21][22] The American loss was 24 killed, 139 wounded and 50 taken prisoner.[3]

Aftermath

The battle had been costly for the British. Apart from the other casualties, losing General Ross was a critical blow to the British. He was a respected leader of British forces in the Peninsular War and the War of 1812. Ross's death proved a blow to British morale as well. The combined effect of the blow suffered at North Point and the failure of the Royal Navy to capture or get past Fort McHenry at the entrance to Baltimore harbor, despite a 25-hour bombardment, proved to be the turning point of the Battle of Baltimore. During the bombardment on Fort McHenry, Francis Scott Key was detained on a British ship, HMS Surprise, under the command of Admiral Cochrane's son, Capt. Thomas Cochrane, but later at the request of the Americans were returned to their truce ship, the "President", under guard by the fleet frigate) at the entrance to Baltimore in the Patapsco River, approximately off the mouth of Colgate Creek, near Old Roads Bay with the rest of the heavier ships of the attacking fleet and witnessed the bombardment of the fort during the rainy, stormy night. Later in the morning, after the Americans fired their morning gun of salute and the regimental band played the tune of "Yankee Doodle", the huge 30 by 42 foot "garrison flag" was raised overhead as the Royal Navy upper-river bombardment ketches and ships made sail and rejoined their heavy warships in evacuating the retreating men of Colonel Brooke as they made their way back down the peninsula from Loudenschlager's/Hampstead Hill to North Point, passing the scene of their earlier battle and wounded and dead. Key wrote a few words and lines of inspiration that morning, and upon the truce ship's return to the "Basin" ("Inner Harbor") later that day and his brief stay at the Indian Queen Hotel, at West Baltimore and Hanover Streets, finished the four paragraphs of the poem/song milling about in his mind, later showing it to his friends including his brother-in-law, Judge and Colonel Joseph Nicolson, (recently returned from commanding an artillery regiment at McHenry) who arranged to have "broadside" handbills printed up under the title of "The Defence of Fort McHenry" at the Baltimore Street offices of the closed newspaper, the "Baltimore American" by the boy apprentice printer, Samuel Sands. Within days the bills were everywhere at both the fort and throughout the city, being whistled, hummed and sang, soon set to the tune of a well-known 18th Century English tune by John Stafford Smith from a musical social, dancing and drinking society, entitled "An Anacreon in Heaven", later soon renamed "The Star-Spangled Banner".

The day after the North Point battle at Godley Wood on the "Patapsco Neck", after resting and treating his wounded men at the Methodist meeting house on the battlefield, Colonel Brooke, now in command, advanced cautiously northwest towards Baltimore. There was no more opposition from Stricker, however he left teams of axemen to fell dozens of trees across the small pathway road through the dense woods and dig trenches to slow up the enemy's troops and artillery. But when the British came into view of the main east-side defenses of Baltimore, Brooke estimated them to be manned by up to 22,000 militia, with 100 cannon ranged in a mile-long stretch of trenches, embankments and bastions from the water's edge near Fells Point to the northeast near the modern Bel Air Road. He prepared to make a night assault against a perceived weak spot in the defenses at Loudenslager Hill, but sent messages to Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane on-board his flagship in the river to send close-in, the bomb ketches with additional small boats and barges loaded with 1,000 Royal Marines to silence the main American battery, "Rodger's Bastion", in the center and the smaller artillery near the shore to the south on the flank of his proposed attack. After 1 a.m. in the early morning of the 14th, (despite losing half his force which got turned in the rain and storm of the night to the wrong direction and headed mistakenly instead to the northeast towards Lazaretto Point and Fells Point opposite the fort) a stiff fight between the boats, commanded by Captain Charles John Napier of the HMS Euryalus and the American smaller supporting batteries at Fort Covington and Fort Babcock, west of McHenry, up the flanking Ferry or Middle Branch. Losing several barges to the returning fire, General Smith and Commodore Rodgers' eastern lines were unharmed and Brooke called off the planned simultaneous eastern attack and began withdrawing before dawn.[23] The British re-embarked at North Point heading out to the Chesapeake Bay.

Legacy

The battle has been commemorated on September 12 for over 200 years since, through the Maryland state, Baltimore City and County holiday of "Defenders' Day" along with observances of the following two days of bombardment at Fort McHenry. It was also immediately remembered beginning the following year with the laying of the cornerstone for the "Battle Monument", the first in the nation to commemorate the common American soldiers whose names were to be inscribed on the column shaft of the Monument, designed by French émigré architect J. Maximilian M. Godefroy at the downtown intersection of North Calvert Street and between East Lexington and East Fayette Streets, at the former long-time central gathering place, Courthouse Square, now vacant, (site of the previous 1769 Baltimore City/County Courthouse, famously known after 1784 as the "Courthouse on Stilts", when stone/brick arches were constructed to preserve the colonial structure and raise the building up and allow Calvert Street to pass to the north underneath, later razed in 1805 and rebuilt to the west of the small square at the southwest corner of Calvert and Lexington Streets) until, which had just months before been proposed for the erection of the new "Washington Monument. After viewing the proposed elaborately detailed design by architect Robert Mills and fearing if the shaft might topple over and hit any of the many expensive substantial townhouses then around the square, the memorial was moved further north of town to the area known as "Howard's Woods" on land donated by Colonel John Eager Howard of Revolutionary War fame. Another cornerstone-laying ceremony occurred the next year and it was completed in 1827. The several phases of the Battle of Baltimore is annually remembered by the meeting beginning in 1815 and continuing in the following decades with the later organization by the 25th Anniversary in 1839 of "The Old Defenders" of the Fort McHenry, North Point and Hampstead Hill soldiers into one of the nation's first veterans organizations which later evolved into the nationwide "General Society of the War of 1812". The historical lineage of the famous 5th Maryland Regiment (the "Dandy Fifth") from the August 1814 Battle of Bladensburg and the Battle of Baltimore in the following month, of the old Third Division and the "Baltimore City Brigade" ("City Brigade") of the Maryland State Militia is perpetuated by the modern 175th Infantry Regiment of the (Maryland Army National Guard, one of nineteen Army National Guard units with campaign credit and flag ribbons for the War of 1812. It also has been called up several times since 1814 to join further in the defense of the country or serve in overseas battles and campaigns (notably in World War I and World War II) with the regular United States Army.

Notes

- ↑ James, p. 321

- 1 2 Battle of North Point - North Point War of 1812 - Battle of North Point Baltimore, in which author Kennedy Hickman says, "While a tactical loss, the Battle of North Point proved to be a strategic victory for the Americans."

- 1 2 3 4 5 1814 British Dead

- 1 2 James, p. 513, reproducing in its entirety 'Return of the killed and wounded, in action with the enemy, near Baltimore, on the 12th of Sept., 1814, Public Record Office, WO 1'

- ↑ James, p. 521

- ↑ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 953.

- ↑ Snow, Peter, "When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington", London: John Murray, 2013. ISBN 978-1250048288.

- ↑ Crawford (2002) pg 273 refers to the number of Marines from each specific ship detachment

- 1 2 3 Brooks and Hohwald, p. 199

- ↑ Laura Rich. Maryland History In Prints 1743-1900. p. 44.

- ↑ Elting, p. 230

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brooks and Hohwald, p. 200

- ↑ Elting, p. 232

- ↑ Snow, Peter (5th June 2014 (John Murray paperback)). When Britain Burned The White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington. John Murray. p. 208. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Snow, Peter (2014). When Britain Burned the White House: The 1814 Invasion of Washington. John Murray. p. 208.

- 1 2 George, p.143

- ↑ Brooks, Hohwald p. 201

- ↑ James, p521, reproducing in its entirety 'a return of killed and wounded belonging to the navy, disembarked with the army under Major General Ross, Sept. 12, 1814, Public Record Office, ADM 1/507'

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16947. pp. 2078–2080. 17 October 1814.

- ↑ Mullaly, Franklin R. (March 1959). "The Battle of Baltimore". Maryland Historical Magazine: 90.

- ↑ Mullaly's sources are: '1. Return of the killed and wounded, in action with the enemy, near Baltimore, on the 12th of Sept., 1814, Public Record Office, WO 1; also, 2. a return of killed and wounded belonging to the navy, disembarked with the army under Major General Ross, Sept. 12, 1814, Public Record Office, ADM 1/507'

- ↑ The Pbenyon website quotes from James publication of 1827 'the total loss of the British on shore amount to 46 killed, and 300 wounded' which appears to be the totals from Debbeig and Cochrane's casualty returns, thereby double-counting the Royal Marine casualties.

- ↑ Elting, pp. 238-242

References and further reading

- Brooks, Victor; Hohwald, Robert (1998). How America Fought Its Wars. Da Capo Press. ISBN 1-58097-002-8.

- Crawford, Michael J. (Ed) (2002). The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, Vol. 3. Washington: United States Department of Defense. ISBN 9780160512247

- Elting, John R. (1995). Amateurs to Arms! A Military History of the War of 1812. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- George, Christopher T. (2001). Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay, Shippensburg, Pa., White Mane, ISBN 1-57249-276-7

- Gleig, George Robert (1827), The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, 1814–1815, London: J. Murray, ISBN 0-665-45385-X

- James, William (1818). A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America. Volume II, London, Printed for the Author. ISBN 0-665-35743-5

- Liston, Kathy Lee Erlandson (2006). "Where Are the British Soldiers Killed in the Battle of North Point Buried?". Fort Howard, MD: Myedgemere.com, LLC. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- Lord, Walter (1994). The Dawn's Early Light, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80-184864-3

- Pitch, Anthony S. (2000). The Burning of Washington, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-425-3

- Whitehorne, Joseph A. (1997). The Battle for Baltimore 1814, Baltimore: Nautical & Aviation Publishing, ISBN 1-877853-23-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of North Point. |

- Detailed Study of the Battle of North Point by John Pezzola

- National Guard Heritage Series painting at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Society of the War of 1812

- Wells & McComas

- Surgeon's Journal of HM troop ship Diomede. (Archive reference ADM 101/96/6 parts 2–5) Transcription of 'Folios 16–17: list of men wounded at Chesapeake on 13 September 1814'