Swansea, Arizona

| Swansea, Arizona | |

|---|---|

| Ghost town | |

|

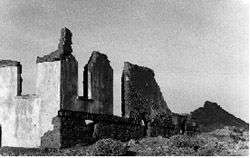

Remnants of Swansea. | |

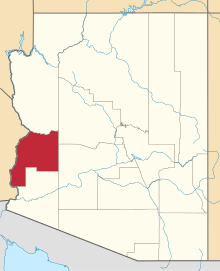

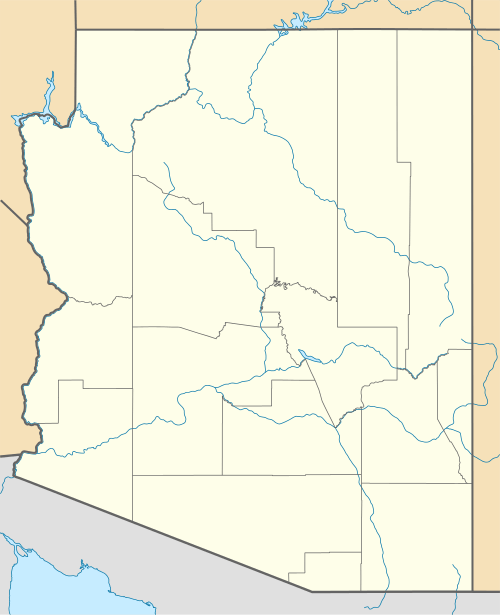

Swansea, Arizona  Swansea, Arizona Location in the state of Arizona | |

| Coordinates: 34°10′12″N 113°50′46″W / 34.17000°N 113.84611°WCoordinates: 34°10′12″N 113°50′46″W / 34.17000°N 113.84611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | La Paz |

| Founded | 1908 |

| Abandoned | 1937 |

| Elevation[1] | 1,283 ft (391 m) |

| Population (2009) | |

| • Total | 0 |

| Time zone | MST (no DST) (UTC-7) |

| Post Office opened | March 25, 1909 |

| Post Office closed | June 28, 1924 |

Swansea is a ghost town in La Paz County in the U.S. state of Arizona. It was settled around 1909 in what was then the Arizona Territory. It served as a mining town as well as a location for processing and smelting the copper ore taken from the nearby mines.

History

Prospecting and mining in the area first began around 1862, but the remote location and lack of transportation kept activity to a minimum. By 1904, the railroad was coming to nearby Parker, and local miners Newton Evans and Thomas Jefferson Carrigan saw an opportunity to develop the area. Within a few years, the two miners had built a 350-ton furnace, a water pipeline to the Bill Williams River, and hoists for five mine shafts.[2][3] They called the new town Signal (not to be confused with the other Arizona ghost town of Signal).[4] By 1908, the claims in the area had been consolidated by the Clara Gold and Copper Mining Company, which set up its headquarters in the mining camp that would become Swansea.[2][3][4] That same year, what was to become the Arizona and Swansea Railroad connected Signal to Bouse some 25 miles (40 km) away. These two factors spurred the growth of the town, and its population quickly grew to about 300 residents.[2][4]

When mining operations first began, the lack of smelting facilities meant that the copper ore had to be sent away for smelting. The destination for most of the ore was Swansea, South Wales, United Kingdom[1][4] and it was sent by way of railroad to the Colorado River, and was then shipped from the Gulf of California around Cape Horn to the United Kingdom. Once a smelter was constructed in 1909, Signal took its new name from the previous location of the smelter they had used in Wales. As such, the destination of the ore sent for smelting remained the same. When the post office was established on March 25, 1909, it was under the name of Swansea.[1][4][5]

At its peak, Swansea boasted an electric light company, an auto dealer, a lumber company, two cemeteries, a saloon, theaters, restaurants, barbershops, an insurance agent, a physician, and of course the local mining and smelting facilities.[3][4]

Decline

The town was short-lived. By 1911, the Clara Consolidated Gold and Copper Mining Company was in financial trouble.[4] The company's promoter in Swansea, George Mitchell, spent considerable sums of money on improvements aimed at attracting investors at the expense of practical improvements to the process of mining, hauling, and processing ore. As a result, the high cost of improvements coupled with the high cost of production meant that the mines could not turn a profit as the per-pound cost of copper production exceeded its price by three cents.[3] The company collapsed in 1912, closing down the mines.[4][5]

After a false start later that year under a new owner, the mines and the town remained quiet until the American Smelting and Refining Company bought the properties in 1914. The new owners restarted mining operations and once again built up the town. Swansea lived on until just after World War I when copper prices dropped, and the town went into a steep decline. Swansea's post office was discontinued on June 28, 1924, and the population dispersed. By 1937, the mines shut down, and Swansea was already a ghost town.[2][3][4][5]

Remnants

Today Swansea is under the protection of the Bureau of Land Management, and constitutes the Swansea Town Site Special Management Area. Due to vandalism and exposure to the weather, the remains of Swansea are in decline. However, you can still see a number of adobe structures, the remains of the railroad depot, two cemeteries, and several mine shafts. The Bureau of Land Management has restored roofs to rows of single-miner's quarters, established an interpretive trail for visitors to Swansea, and is engaged in efforts to shore up other structures. In addition, there are many stone foundations where buildings once stood.[2][3]

Geography

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 400 | — | |

| 1920 | 337 | −15.7% | |

| 1930 | 0 | −100.0% | |

| Source:[6] | |||

Swansea is located approximately 25 miles (40 km) northeast of both Bouse and the town of Parker at 34°10′12″N 113°50′46″W / 34.17000°N 113.84611°W (34.1700198, -113.8460490). The site is remote, and is only accessible via rough, gravel roads.[1][2][4]

Demographics

US Census data placed the population of the town at 400 in 1910 shortly after it was founded, and 337 in 1920, shortly before it was abandoned.[6] By some accounts, the town's population peaked at about 750 residents, though the rapid rise and fall of the town coupled with the timing of the collection of population data make that figure difficult to substantiate.[4]

Popular culture

- In the Chris Ryan novel, Blackout, Swansea is the location of Luke's hideout.

- The training scenes in the 1971 film The Day of the Wolves were shot in Swansea.

See also

- American Old West

- Boomtown

- History of Arizona

- List of ghost towns in Arizona

- Copper mining in Arizona

References

- 1 2 3 4 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Swansea

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Swansea Historic Townsite". Bureau of Land Management. January 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Varney, Philip (April 2005). "Ghosts of the Rivers". In Stieve, Robert. Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps: A Travel Guide to History (10th ed.). Phoenix, Arizona: Arizona Highways Books. pp. 48–51. ISBN 1-932082-46-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sherman, James E.; Barbara H. Sherman (1969). "Swasea". Ghost Towns of Arizona (First ed.). University of Oklahoma Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-8061-0843-6.

- 1 2 3 Granger, Byrd H. (1970). Arizona Place Names. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 386. ISBN 0-8165-0009-6.

- 1 2 Moffat, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 9–17. ISBN 0-8108-3033-7.

External links

- Swansea Historic Townsite - Bureau of Land Management

- Swansea at Ghosttowns.com

- Swansea at Ghost Town Gallery