Théodore Chassériau

Théodore Chassériau (September 20, 1819 – October 8, 1856) was a Dominican/French Romantic painter noted for his portraits, historical and religious paintings, allegorical murals, and Orientalist images inspired by his travels to Algeria.

Life and work

Chassériau was born in El Limón, Samaná, in the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic).[1] His father Benoît Chassériau was a French adventurer who had arrived in Santo Domingo in 1802 to take an administrative position in what was until 1808 a French colony.[2] Theodore's mother, Maria Magdalena Couret de la Blagniére, was the daughter of a mulatto landowner born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). In December 1820 the family left Santo Domingo for Paris, where the young Chassériau soon showed precocious drawing skill. He was accepted into the studio of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in 1830, at the age of eleven, and became the favorite pupil of the great classicist, who regarded him as his truest disciple.[3] (An account that may be apocryphal has Ingres declaring "Come, gentlemen, come see, this child will be the Napoleon of painting.")[4]

After Ingres left Paris in 1834 to become director of the French Academy in Rome, Chassériau fell under the influence of Eugène Delacroix, whose brand of painterly colorism was anathema to Ingres. Chassériau's art has often been characterized as an attempt to reconcile the classicism of Ingres with the romanticism of Delacroix.[5] He first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1836, and was awarded a third-place medal in the category of history painting.[6] In 1840 Chassériau travelled to Rome and met with Ingres, whose bitterness at the direction his student's work was taking led to a decisive break.

.jpg)

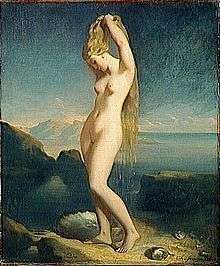

Among the chief works of his early maturity are Susanna and the Elders and Venus Anadyomene (both 1839), Diana Surprised by Actaeon (1840), Andromeda Chained to the Rock by the Nereids (1840), and The Toilette of Esther (1841), all of which reveal a very personal ideal in depicting the female nude.[7] Chassériau's major religious paintings from these years, Christ on the Mount of Olives (a subject he treated in 1840 and again in 1844) and The Descent from the Cross (1842), received mixed reviews from the critics; among the artist's champions was Théophile Gautier. Chassériau also carried out a commission for murals depicting the life of Saint Mary of Egypt in the Church of Saint-Merri in Paris; these were completed in 1843.

Portraits from this period include the Portrait of the Reverend Father Dominique Lacordaire, of the Order of the Predicant Friars (1840), and The Two Sisters (1843), which depicts Chassériau's sisters Adèle and Aline.

Throughout his life he was a prolific draftsman; his many portrait drawings executed with a finely pointed graphite pencil are close in style to those of Ingres. He also created a body of 29 prints, including a group of eighteen etchings of subjects from Shakespeare's Othello in 1844.[8]

In 1846, shortly after painting the colossal Ali-Ben-Hamet, Caliph of Constantine and Chief of the Haractas, Followed by his Escort, Chassériau made his first trip to Algeria. From sketches made on this and subsequent trips he painted such subjects as Arab Chiefs Visiting Their Vassals and Jewish Women on a Balcony (both 1849, now in the Louvre). A major late work, The Tepidarium (1853, in the Musée d'Orsay), depicts a large group of women drying themselves after bathing, in an architectural setting inspired by the artist's trip in 1840 to Pompeii. His most monumental work was his decoration of the grand staircase of the Cour des Comptes, commissioned by the state in 1844 and completed in 1848. This work was heavily damaged in May 1871 by a fire set during the Commune, and only fragments could be recovered; these are preserved in the Louvre.

After a period of ill health, exacerbated by his exhausting work on commissions for murals to decorate the Churches of Saint-Roch and Saint-Philippe-du-Roule, Chassériau died at the age of 37 in Paris, on October 8, 1856.

His work had a significant impact on the style of Puvis de Chavannes and Gustave Moreau, and—through those artists' influence—reverberations in the work of Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse.[9] There is in Paris a Society for the painter: Association des Amis de Théodore Chassériau.

Works of Chassériau are today visible in the Musée du Louvre where a room is dedicated to him, in the Musée d'Orsay or in the Musée de Versailles. Collections in the United States holding works by Théodore Chassériau include the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University, the National Gallery of Art of Washington, D.C., the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Museum of the Art Rhode Island School of Design, The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Selected works

- Self-portrait (Chassériau) - Musée du Louvre

- Aline Chassériau - Musée du Louvre

- Battle of Arab Horsemen Around a Standard (1854) - Dallas Museum of Art

Exhibitions

- Théodore Chassériau : Parfum exotique - National Museum of Western Art of Tokyo - Japan, planned from Feb 28th to May 28, 2017

- Théodore Chassériau : Obras sobre papel - Galerie nationale des beaux-arts de Santo Domingo and Centro cultural León de Santiago de los Caballeros - Dominican republic, 2004

- Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856) - A different Romanticism - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (United States), Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris (France) and Musée des beaux-arts de Strasbourg (France), 2002

- Chassériau (1819-1856) : exposition au profit de la Société des amis du Louvre - Galerie Daber, Paris - France, 1976

- Theodore Chassériau (1819-1856) - Musée des beaux-arts de Poitiers - France, 1969

- Théodore Chassériau - Musée national des beaux-arts d'Alger - Algeria, 1936

- Restrospective Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856) - Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris - France, 1933

- Aquarelles et dessins de Chasseriau (1819-1856) - Galerie L. Dru, Paris - France, 1927

- Les Peintres orientalistes français - 4e exposition : Rétrospective Théodore Chassériau - Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris - France, 1897

Gallery

Othello and Desdemona in Venice, 1850, oil on wood, 25 x 20 cm, in the Louvre, Paris. Another work inspired by Shakespeare

Othello and Desdemona in Venice, 1850, oil on wood, 25 x 20 cm, in the Louvre, Paris. Another work inspired by Shakespeare Le Harem, ca. 1851–1852, oil on wood, 49 x 39 cm.

Le Harem, ca. 1851–1852, oil on wood, 49 x 39 cm. Tepidarium, 1853, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay.

Tepidarium, 1853, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay.

References

- Fisher, Jay M.(1979). Théodore Chassériau: Illustrations for Othello. Baltimore: The Baltimore Museum of Art. ISBN 0-912298-50-2

- Guégan, Stéphane; Pomarède, Vincent; Prat, Louis-Antoine (2002). Théodore Chassériau, 1819-1856: the unknown romantic. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 1-58839-067-5

- Miller, Peter Benson (2004). "By the Sword and the Plow: Théodore Chassériau's Cour des Comptes Murals and Algeria," The Art Bulletin vol. 86, no. 4 (Dec. 2004), pp. 690–718.

- Rosenblum, Robert (1989). Paintings in the Musée d'Orsay. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 1-55670-099-7

Further reading

- Chassériau Correspondance oubliée, édition présentée et annotée par Jean-Baptiste Nouvion. Préface par Marianne de Tolentino - Les Amis de Théodore Chassériau, 260 pages, Paris, 2014

- Aglaus Bouvenne Théodore Chassériau : Souvenirs et Indiscrétions (1884), réédition par Les Amis de Théodore Chassériau, 2012 (en langue française), 2013 (en langue espagnole)

- Xavier de Harlay, « L'Idéal moderne selon Charles Baudelaire & Théodore Chassériau », revue Art et Poésie de Touraine numéro 180, 2005 et éditions Litt&graphie, 2011

- André-Pierre Nouvion, Trois familles en Périgord-Limousin dans la tourmente de la Révolution et de L'Empire : Nouvion, Besse-Soutet-Dupuy et Chassériau, Paris, 2007

- Louis-Antoine Prat, Cahiers du Dessin Français numéro 5. Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856), Galerie de Bayser, 1989

- Christine Peltre, Théodore Chassériau, Gallimard, 2002

- Louis-Antoine Prat, Dessins de Théodore Chassériau: 1819-1856, 2 vol., Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des dessins, Paris : Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1988

- Marc Sandoz, Théodore Chassériau, 1819 1856, catalogue raisonné des peintures et estampes. Paris : Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1974

- Werner Teupser, Theodore Chasseriau, Zeitschrift für Kunst

- Léonce Bénédite, Théodore Chassériau: sa vie et son œuvre, Paris, 1931

- Goodrich, Théodore Chassériau, 1928

- Henri Focillon, « La peinture au XIXe : Le retour à l'antique » in Le Romanticisme, Paris, 1927

- Jean Laran, Théodore Chassériau, Paris, 1913, 1921

- Léandre Vaillat, « L'Œuvre de Théodore Chassériau » in Les Arts, août 1913

- Léandre Vaillat, « Chassériau » in L'Art et les Artistes, 1907

- Valbert Chevillard, « Théodore Chassériau » in Revue de l'art ancien et moderne, numéro 3, 10 mars 1898,

- Alice et Aline, une peinture de Théodore Chassériau, par Robert de Montesquiou Ed. Charpentier et Fasquelle, Paris, 1898

- La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, numéro 9, 27 février 1897

- Ary Renan, Les Peintres orientalistes, Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1897

- Valbert Chevillard, Un peintre romantique : Théodore Chassériau, Paris, 1893

- Aglaus Bouvenne Théodore Chassériau : Souvenirs et Indiscrétions, A. Detaille, Paris, 1884

- Théophile Gautier, « L'Atelier de feu Théodore Chassériau » in L'Artiste, numéro 14, 15 mars 1857

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Théodore Chassériau. |

- Site web des 'Amis de Théodore Chassériau' (France)

- insecula (Chasseriau)

- Famille Chasseriau, Généalogie d'Haiti et de Saint-Domingue

- Portrait de femme

- Théodore Chassériau exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Retrieved on April 15, 2007.