The Aviator (2004 film)

| The Aviator | |

|---|---|

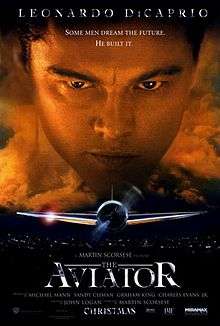

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Produced by |

Michael Mann Sandy Climan Graham King Charles Evans, Jr. |

| Written by | John Logan |

| Starring |

Leonardo DiCaprio Cate Blanchett Kate Beckinsale John C. Reilly Alec Baldwin Alan Alda Jude Law |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

Warner Bros. Pictures Miramax Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 170 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $110 million |

| Box office | $213.7 million[1] |

The Aviator is a 2004 American biographical drama film directed by Martin Scorsese, written by John Logan. It stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes, Cate Blanchett as Katharine Hepburn and Kate Beckinsale as Ava Gardner. The supporting cast features Ian Holm, John C. Reilly, Alec Baldwin, Jude Law as Errol Flynn, Gwen Stefani as Jean Harlow, Kelli Garner as Faith Domergue, Willem Dafoe, Alan Alda, and Edward Herrmann.

Based on the 1993 non-fiction book Howard Hughes: The Secret Life by Charles Higham, the film depicts the life of Howard Hughes, an aviation pioneer and director of Hell's Angels. The film portrays his life from 1927–1947 during which time Hughes became a successful film producer and an aviation magnate while simultaneously growing more unstable due to severe obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).

The Aviator was released in the United States on December 25, 2004. The film grossed $214 million at the box office. It was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor in a Leading Role for DiCaprio, and Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Alda, winning five for Best Cinematography, Best Film Editing, Best Costume Design, Best Art Direction and Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Cate Blanchett.

Plot

In 1913 Houston, nine-year-old Howard Hughes is warned by his mother about diseases from which she is afraid he will succumb. Fourteen years later, he begins to direct the film Hell's Angels. However, after the release of The Jazz Singer, the first partially talking film, Hughes becomes obsessed with shooting his film realistically, and decides to convert the movie to a sound film. Despite the film being a hit, Hughes remains unsatisfied with the end result and orders the film to be recut after its Hollywood premiere. He becomes romantically involved with actress Katharine Hepburn, who helps to ease the symptoms of his worsening obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

In 1935, Hughes test flies the H-1 Racer, pushing it to a new speed record. Three years later, he breaks the world record by flying around the world in four days. He subsequently purchases majority interest in Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA), aggravating Juan Trippe, company rival and chairman of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am). Trippe gets his friend, Senator Owen Brewster, to introduce the Community Airline Bill, giving Pan Am exclusivity on international air travel. As Hughes' fame grows, he is linked to various starlets, causing a jealous Hepburn to break up with him following her announcement that she has fallen in love with fellow actor Spencer Tracy. Hughes quickly finds a new love interest with 15-year-old Faith Domergue, and later actress Ava Gardner.

Hughes secures a contract with the Army Air Forces for two projects: a spy aircraft and a troop transport unit. In 1946, with the "Spruce Goose" flying boat still in construction, Hughes finishes the XF-11 reconnaissance aircraft and takes it for a test flight. However, one of the engines fails midflight, and the aircraft crashes in Beverly Hills, with Hughes getting severely injured. With the end of World War II, the army cancels its order for the H-4 Hercules, although Hughes still continues the development with his own money. When he is discharged, he is informed that he must choose between funding the airlines or his 'flying boat'. Hughes orders Noah Dietrich to mortgage the TWA assets so he can continue the development.

Hughes becomes increasingly paranoid, planting microphones and tapping Gardner's phone lines to keep track of her. His home is searched by the FBI for incriminating evidence of war profiteering, provoking a powerful psychological trauma on Hughes, with the men searching his possessions and tracking dirt through his house. Brewster privately offers to drop the charges if Hughes sells the TWA to Trippe, but is rejected. With Hughes in a deep depression, Trippe has Brewster summon him for a Senate investigation, certain that Hughes will not show up. With Hughes shut away for nearly three months, Gardner visits him and personally grooms and dresses him in preparation for the hearing.

Hughes defends himself against Brewster's charges and accuses Trippe of bribing the senator. Hughes concludes by announcing that he has committed to completing the H-4 aircraft, and that he will leave the country if he could not get it to fly. After successfully flying the aircraft, Hughes speaks with Dietrich and his engineer, Glenn Odekirk, about a new jetliner for TWA. However, the sight of men in germ-resistant suits causes Hughes to have a mental breakdown. As Odekirk hides him in a restroom while Dietrich fetches a doctor, Hughes begins to have flashbacks of his childhood, his obsession for aviation, and his ambition for success, repeating the phrase, "the way of the future".

Cast

- Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes

- Cate Blanchett as Katharine Hepburn

- John C. Reilly as Noah Dietrich

- Kate Beckinsale as Ava Gardner

- Alec Baldwin as Juan Trippe

- Alan Alda as Senator Owen Brewster

- Ian Holm as Professor Fitz

- Danny Huston as Jack Frye

- Gwen Stefani as Jean Harlow

- Jude Law as Errol Flynn

- Willem Dafoe as Roland Sweet

- Adam Scott as Johnny Meyer

- Matt Ross as Glenn "Odie" Odekirk

- Kevin O'Rourke as Spencer Tracy

- Kelli Garner as Faith Domergue

- Frances Conroy as Katharine Houghton

- Brent Spiner as Robert E. Gross

- Stanley DeSantis as Louis B. Mayer

- Edward Herrmann as Joseph Breen

- J. C. MacKenzie as Ludlow Ogden Smith

- Josie Maran as Thelma the Cigarette Girl

Production

Development

Warren Beatty planned to direct and star in a Hughes biopic in the early 1970s. He co-wrote the script with Bo Goldman after a proposed collaboration with Paul Schrader fell through. Goldman wrote his own script, Melvin and Howard, which depicted Hughes' possible relationship with Melvin Dummar. Beatty's thoughts regularly returned to the project over the years,[2] and in 1990 he approached Steven Spielberg to direct Goldman's script, but the project never materialized.[3] Charles Evans, Jr. purchased the film rights of Howard Hughes: The Untold Story (ISBN 0-525-93785-4) in 1993. Evans secured financing from New Regency Productions, but development stalled.[4]

The Aviator was a joint production between Warner Bros, which handled Latin American and Canadian distribution, and Disney, which released the film internationally under its Miramax Films banner in the US and the UK. Disney previously developed a Hughes biopic with director Brian De Palma and actor Nicolas Cage between 1997 and 1998. Titled Mr. Hughes, the film would have starred Cage in the dual roles of both Hughes and Clifford Irving. It was conceived when De Palma and Cage were working on Snake Eyes with writer David Koepp.[2][5] Universal Pictures joined the competition in March 1998 when it purchased the film rights to Empire: The Life, Legend and Madness of Howard Hughes (ISBN 0-393000-257), written by Donald Barlett and James Steele. The Hughes brothers were going to direct Johnny Depp as Howard Hughes, based on a script by Terry Hayes,[6] Universal canceled it when it decided it did not want to fast-track development to compete with Disney. Following the disappointing release of Snake Eyes in August 1998, Disney placed Mr. Hughes in turnaround.

Disney restarted development on a new Howard Hughes biopic in June 1999, hiring Michael Mann to direct Leonardo DiCaprio playing the role of Howard Hughes, based on a script by John Logan.[7] The studio put it in turnaround again following the disappointing box-office performance of Mann's critically acclaimed The Insider. New Line Cinema picked it up in turnaround almost immediately, with Mann planning to direct after finishing Ali.[8] Mann was eventually replaced with DiCaprio's Gangs of New York director Martin Scorsese. Scorsese later said that he "grossly misjudged the budget".[9]

Howard Hughes suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), most notably an obsession with germs and cleanliness. Scorsese and DiCaprio worked closely with Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz, Ph.D. of UCLA, to portray the most accurate depiction of OCD. The filmmakers had to focus both on previous accounts of Hughes’ behaviors as well as the time period, given that when Hughes was suffering, there was no psychiatric definition for what ailed him. Instead of receiving proper treatment, Hughes was forced to hide his stigmatized compulsions; his disorder began to conflict with everyday functioning, eventually destroying his once-successful career.

DiCaprio dedicated hundreds of hours of work to portray Hughes’ unique case of OCD on screen. Apart from doing his research on Hughes, DiCaprio met with people suffering from OCD. In particular, he focused on the way some individuals would wash their hands, later inspiring the scene in which he cuts himself scrubbing in the bathroom. The character arc of Howard Hughes was a drastic one: from the height of his career to the appearance of his compulsions and, eventually, to him sitting naked in a screening room, refusing to leave, and later repeating the phrase “the way of the future.”[10]

Cinematography

In an article for the American Cinematographer, John Pavlus wrote: "The film boasts an ambitious fusion of period lighting techniques, extensive effects sequences and a digital re-creation of two extinct cinema color processes: two-color and three-strip Technicolor."[11] For the first 52 minutes of the film, scenes appear in shades of only red and cyan blue; green objects are rendered as blue. This was done, according to Scorsese, to emulate the look of early bipack color films, in particular the Multicolor process, which Hughes himself owned, emulating the available technology of the era. Similarly, many of the scenes depicting events occurring after 1935 are treated to emulate the saturated appearance of three-strip Technicolor. Other scenes were stock footage colorized and incorporated into the film. The color effects were created by Legend Films.[12]

Production design

Scale models were used to duplicate many of the flying scenes in the film. When Martin Scorsese began planning his aviation epic, a decision was made to film flying sequences with scale models rather than CGI special effects. The critical reaction to the CGI models in Pearl Harbor (2001) had been a crucial factor in Scorsese's decision to use full-scale static and scale models in this case. The building and filming of the flying models proved both cost-effective and timely.[13]

The primary scale models were the Spruce Goose and the XF-11; both miniatures were designed and fabricated over a period of several months by New Deal Studios.[14] The 375 lb (170 kg) Spruce Goose model had a wingspan of 20 ft (6.1 m) while the 750 lb (340 kg) XF-11 had a 25 ft (7.6 m) wingspan. Each was built as a motion control miniature used for "beauty shots" of the model taking off and in flight as well as in dry dock and under construction at the miniature Hughes Hangar built as well by New Deal Studios. The XF-11 was reverse engineered from photographs and some rare drawings and then modeled in Rhinoceros 3D by the New Deal art department. These 3D models of the Spruce Goose as well as the XF-11 were then used for patterns and construction drawings for the model makers. In addition to the aircraft, the homes that the XF-11 crashes into were fabricated at 1:4 scale to match the 1:4 scale XF-11. The model was rigged to be crashed and break up several times for different shots.[13]

Additional castings of the Spruce Goose flying boat and XF-11 models were provided for new radio controlled flying versions assembled by the team of model builders from Aero Telemetry. The Aero Telemetry team was given only three months to complete three models including the 450 lb H-1 Racer, with an 18 ft (5.5 m) wingspan, that had to stand-in for the full-scale replica that was destroyed in a crash, shortly before principal photography began.[15]

The models were shot on location at Long Beach and other California sites from helicopter or raft platforms. The short but much heralded flight of Hughes’ HK-1 Hercules on November 2, 1947 was realistically recreated in the Port of Long Beach. The motion control Spruce Goose and Hughes Hangar miniatures built by New Deal Studios are presently on display at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon, with the original Hughes HK-1 "Spruce Goose".[13]

Release

Distribution

Miramax Films distributed the film in the United States, the United Kingdom as well as Italy, France and Germany. Miramax also held the rights to the US television distribution, while Warner Bros. Pictures retained the rights for home video/DVD distribution and the theatrical release in the United States, Canada and Latin America. Initial Entertainment Group released the film in the remaining territories around the world.[16]

Box office performance

The Aviator was given a limited release on December 17, 2004 in 40 theaters where it grossed $858,021 on its opening weekend.[17] It was given a wide release on December 25, 2004, and opened in 1,796 theaters in the United States, grossing $4.2 million on its opening day and $8.6 million in its opening weekend, ranking #4 with a per theater average of $4,805.[18][19] On its second weekend, it moved up to #3 and grossed $11.4 million – $6,327 per theater.[20] The film grossed $102.6 million in the United States and Canada and $111.1 million overseas, for a worldwide total of $213.7 million, against an estimated production cost of $110 million.[21]

Home media

The film was released in DVD in a two-disc-set in widescreen and full screen versions on May 24, 2005.[22] The first disc includes commentary with director Martin Scorsese, editor Thelma Schoonmaker and producer Michael Mann. The second disc includes "The Making of 'The Aviator' ", "Deleted Scenes", "Behind the Scenes", "Scoring The Aviator", "Visual Effects", featurettes on Howard Hughes as well as other special features. The DVD was nominated for Best Audio Commentary (New to DVD) at the DVD Exclusive Awards in 2006.

The film was later released in High Definition on Blu-ray Disc and HD DVD on November 6, 2007.[22]

Critical response

The Aviator received generally positive reviews. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 87% approval rating based on reviews from 213 critics, with an average rating of 7.8 out of 10. The site's critical consensus states: "With a rich sense of period detail, The Aviator succeeds thanks to typically assured direction from Martin Scorsese and a strong performance from Leonardo DiCaprio, who charts Howard Hughes' descent from eccentric billionaire to reclusive madman."[23] On Metacritic, the film received a weighted average score of 77 out of 100 based on 41 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[24]

Roger Ebert of Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four and described the film and its subject, Howard Hughes, in these terms: "What a sad man. What brief glory. What an enthralling film...There's a match here between Scorsese and his subject, perhaps because the director's own life journey allows him to see Howard Hughes with insight, sympathy – and, up to a point, with admiration. This is one of the year's best films."[25] In his review for The Daily Telegraph, Sukhdev Sandhu praised Scorsese's direction, DiCaprio and the supporting cast but considered Beckinsale 'miscast'. Of the film, he said it is "a gorgeous tribute to the Golden Age of Hollywood" even though it "tips the balance of spectacle versus substance in favour of the former."[26] David T. Courtwright in The Journal of American History characterized The Aviator as a technically brilliant and emotionally disturbing film. According to him, the main achievement for Scorsese is that he managed to restore the name of Howard Hughes as a pioneer aviator.[27]

Accolades

See also

References

- ↑ "The Aviator (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- 1 2 David Hughes (March 2004). Tales From Development Hell. London: Titan Books. pp. 136–140. ISBN 1-84023-691-4.

- ↑ Joseph McBride (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York City: Faber and Faber. p. 446. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ↑ Hughes, p.144-147

- ↑ Staff (1998-08-06). "'Snake' trio tackles Hughes; LaPaglia in 'Sam'". Variety. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Staff (March 2, 1998). "Hughes team tags Depp; 'Spider' rumors fly". Variety. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ↑ Chris Petrikin; Michael Fleming (June 24, 1999). "Mouse, Mann and DiCaprio pact". Variety. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ↑ Michael Fleming (February 25, 2000). "New Line spruced up". Variety. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Scorsese overspends on 'The Aviator'". Digital Spy. December 8, 2004. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Kinsey, Beck. "The Affliction of Howard Hughes: OCD - Aviator - Martin Scorsese - Leonardo DiCaprio" January 2014 via youtube.com. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ↑ Pavlus, John (January 2005). "Robert Richardson, ASC exploits modern methods to craft a classic look for The Aviator, an epic that details the ambitions that drove Howard Hughes". American Cinematographer. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ↑ "The Aviator: Visual Effects – Behind the Scenes". AviatorVFX.com. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Cobb, Jerry (February 25, 2005). "Movie Models are the real stars of 'The Aviator'". MSNBC. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- ↑ "New Deal Studios." NewDealStudios.com. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Baker, Mark. "Cottage Grove pilot dies in replica of historic plane." The Register-Guard, August 6, 2003 via ArticleArchives.com. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Miramax Gets Distribution Rights to 'The Aviator'." Miramax Films via About.com: Hollywood Movies. Retrieved: February 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 17–19, 2004". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 24–26, 2004". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Daily Box Office Results for December 25, 2004". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 31–January 2, 2005". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ "The Aviator (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- 1 2 "The Aviator (2004)". www.dvdreleasedates.com. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Aviator (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ "The Aviator". Metacritic. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 23, 2004). "The Aviator Movie Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Thrillingly bumpy ride towards madness". The Daily Telegraph. December 24, 2004. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ Courtwright, David T. "The Aviator". The Journal of American History. Oxford University Press. 92 (3). JSTOR 3660141.

Further reading

- Floyd, Jim. The Avro Canada C102 Jetliner. Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1986. ISBN 0-919783-66-X.

- Higham, Charles. Howard Hughes: The Secret Life. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2004. ISBN 978-0-312-32997-6.

- Maguglin, Robert O. Howard Hughes, His Achievements & Legacy: the Authorized Pictorial Biography. Long Beach, California: Wrather Port Properties, 1984. ISBN 0-86679-014-4.

- Marrett, George J. Howard Hughes: Aviator. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2004. ISBN 1-59114-510-4.

- Wegg, John. General Dynamic Aircraft and their Predecessors. London: Putnam, 1990. ISBN 0-85177-833-X.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Aviator (2004 film) |

- Official website

- The Aviator at the Internet Movie Database

- The Aviator at the TCM Movie Database

- The Aviator at AllMovie

- The Aviator at the American Film Institute Catalog