The Lady and the Unicorn

The Lady and the Unicorn (French: La Dame à la licorne) is the modern title given to a series of six tapestries woven in Flanders from wool and silk, from designs ("cartoons") drawn in Paris around 1500.[1] The set, on display in the Musée national du Moyen Âge (former Musée de Cluny) in Paris, is often considered one of the greatest works of art of the Middle Ages in Europe.

Five of the tapestries are commonly interpreted as depicting the five senses – taste, hearing, sight, smell, and touch. The sixth displays the words "À mon seul désir". The tapestry's meaning is obscure, but has been interpreted as representing love or understanding. Each of the six tapestries depicts a noble lady with the unicorn on her left and a lion on her right; some include a monkey in the scene. The pennants, as well as the armour of the Unicorn and Lion in the tapestry bear the arms of the sponsor, Jean Le Viste, a powerful nobleman in the court of King Charles VII. However, a very recent study of the heraldry appears to lend credence to another hypothesis - previously dismissed - that the real sponsor of the tapestry is Antoine II Le Viste (1470-1534), a descendant of the younger branch of the Le Viste family and an important figure at the court of Charles VIII, Louis XII and François I.[2]

The tapestries are created in the style of mille-fleurs (meaning: "thousand flowers").

The tapestries were rediscovered in 1841 by Prosper Mérimée in Boussac castle (owned at the time by the subprefect of the Creuse) where they had been suffering damage from their storage conditions. In 1844 the novelist George Sand saw them and brought public attention to the tapestries in her works at the time (most notably in her novel Jeanne), in which she correctly dated them to the end of the fifteenth century, using the ladies' costumes for reference.[3] Nevertheless, the artefacts continued to be threatened by damp and mould until 1863, when they were brought to the Thermes du Cluny in Paris. Careful conservation has restored them nearly to their former glory. They are presently on display in the Musée de Cluny (Musée du Moyen-Âge), Paris.

The tapestries

- Touch

The lady stands with one hand touching the unicorn's horn, and the other holding up the pennant. The lion sits to the side and looks on.

- Taste

The lady is taking sweets from a dish held by a maidservant. Her eyes are on a parakeet on her upheld left hand. The lion and the unicorn are both standing on their hind legs reaching up to pennants that frame the lady on either side. The monkey is at her feet, eating one of the sweetmeats.

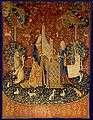

- Smell

The lady stands, making a wreath of flowers. Her maidservant holds a basket of flowers within her easy reach. Again, the lion and unicorn frame the lady while holding on to the pennants. The monkey has stolen a flower which he is smelling, providing the key to the allegory.

- Hearing

The lady plays a portative organ on top of a table covered with a Oriental rug. Her maidservant stands to the opposite side and operates the bellows. The lion and unicorn once again frame the scene holding up the pennants. Just as on all the other tapestries, the unicorn is to the lady's left and the lion to her right - a common denominator to all the tapestries.

- Sight

The lady is seated, holding a mirror up in her right hand. The unicorn kneels on the ground, with his front legs in the lady's lap, from which he gazes at his reflection in the mirror. The lion on the left holds up a pennant.

- À Mon Seul Désir

This tapestry is wider than the others, and has a somewhat different style. The lady stands in front of a tent, across the top of which is written "À Mon Seul Désir", an obscure motto, variously interpretable as "my one/sole desire", "according to my desire alone"; "by my will alone", "love desires only beauty of soul", "to calm passion". Her maidservant stands to the right, holding open a chest. The lady is placing the necklace she wears in the other tapestries into the chest. To her left is a low bench with a dog sitting on a decorative pillow. It is the only tapestry in which she is seen to smile. The unicorn and the lion stand in their normal spots framing the lady while holding onto the pennants.

This tapestry has elicited a number of interpretations. One interpretation sees the lady putting the necklace into the chest as a renunciation of the passions aroused by the other senses, and as an assertion of her free will. Another sees the tapestry as representing a sixth sense of understanding (derived from the sermons of Jean Gerson of the University of Paris, c. 1420). Various other interpretations see the tapestry as representing love or virginity. It is also debated whether the lady in "À Mon Seul Désir" is picking up or setting aside the necklace.

In The Lady with the Unicorn tapestry series, it is generally accepted that the first five tapestries represent the five senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. The interpretation of the sixth tapestry, “À Mon Seul Désir,” remains uncertain. [4]

A new proposal suggests that the French words, “à mon seul désir,” translate to “with my unique desire,” meaning that people are the only species that covet material objects even as we share the five senses with animals. The tapestries appear to be arranged to show that while we share the five senses, we are unique in our want of valuable possessions. In the scenario depicted in the last tapestry, it is unclear whether the lady is taking her necklace from the box held by her maid or putting it away, but that distinction doesn’t matter. The point is that she treasures the golden necklace.

In the first five tapestries, one or more of the animals are shown utilizing the represented sense along with the women. In “Sight,” the unicorn is gazing at itself in a mirror held by the lady. Presumably, all of the animals can hear the music being played by the women in the “Hearing” tapestry. In “Taste,” a monkey is eating a sweetmeat as the lady takes a sweet from a bowl held by her maid, and in “Smell,” the monkey is sniffing a flower as the lady assembles a flower wreath. The “Touch” tapestry features the lady’s hand touching the unicorn’s horn. In the final tapestry, only the two women are engaged in handling the necklace, while some of the animals seem to watch from afar. The blue tent in the last tapestry also serves to separate the human figures from the natural world, which includes the unicorn with its mythical qualities. The tent frames the lady handling her necklace with a strip of cloth and her maid and is not present in any of the previous tapestries. In all of the tapestries except “Smell,” a falcon, sometimes wearing jesses, is hunting another bird. In the sixth tapestry, this occurs above and outside of the tent and may represent hunting as another trait or proclivity shared between people and animals.

The interpretation of people alone valuing material objects ties the individual representations of the six tapestries together and allows them to flow towards the realization that, while people may live alongside the natural and mythical worlds (which, in medieval times, were likely considered the same), they remain separate and not completely in either due to their unique desires.

In popular culture

- The tapestries are described in detail by the narrator of Rainer Maria Rilke's novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.

- The Lady and the Unicorn is the title of a 1970 album by the English folk guitarist John Renbourn, comprising arrangements of early music. It shows the tapestry À Mon Seul Désir on its cover.

- These tapestries are depicted in the novel The Lady and the Unicorn by Tracy Chevalier.

- Several of the tapestries can be seen hanging on the walls of the Gryffindor Common Room in the Harry Potter series of films.

- The six tapestries have inspired the six movements of Kaija Saariaho's clarinet concerto D'om le Vrai Sens: the title is an anagram of "A mon seul désir".

- The tapestries are featured heavily in the novel Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn.

- One of the tapestries can be found hanging in the Musée Crune in the game Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars.

- The tapestry Sight is the cover art of Anonymous 4's 1994 early music album Love's Illusion: Music from the Montpellier Codex 13th Century.

- The tapestries' orange trees were adapted and redesigned by artist Leon Coward for the mural The Happy Garden of Life in the 2016 sci-fi movie 2BR02B: To Be or Naught to Be.[5] The mural also makes use of the millefleur style.

Gallery

Touch 3.15 m x 3.58 m (12 ft 14 in x 11 ft 9 in)

Touch 3.15 m x 3.58 m (12 ft 14 in x 11 ft 9 in) Taste 3.75 m x 4.60 m (12 ft 4 in x 15 ft 1 in)

Taste 3.75 m x 4.60 m (12 ft 4 in x 15 ft 1 in) Smell 3.67 m x 3.22 m (11 ft 11 in x 10 ft 7 in)

Smell 3.67 m x 3.22 m (11 ft 11 in x 10 ft 7 in) Hearing 3.70 m x 2.90 m (12 ft 2 in x 9 ft 6 in)

Hearing 3.70 m x 2.90 m (12 ft 2 in x 9 ft 6 in) Sight 3.10 m x 3.30 m (10 ft 2 in x 10 ft 10 in)

Sight 3.10 m x 3.30 m (10 ft 2 in x 10 ft 10 in) "À Mon Seul Désir" 3.80 m x 4.64 m (12 ft 4 in x 14 ft 10 in)

"À Mon Seul Désir" 3.80 m x 4.64 m (12 ft 4 in x 14 ft 10 in) The Dame à la licorne room of the Musée national du Moyen Âge (former Musée de Cluny)

The Dame à la licorne room of the Musée national du Moyen Âge (former Musée de Cluny)

See also

Notes

- ↑ See the six tapestries at the Musée du Moyen-Âge website

- ↑ Carmen Decu Teodorescu, "La tenture de la Dame la licorne : nouvelle lecture des armoiries", in Bulletin Monumental, Société française d'archéologie, n° 168-4, 2010, pp. 355-367. The coat of arms that appears on the tapestry was attributed by specialists to the older branch and to the chief of the Le Viste family, Jean IV Le Viste, but it blatantly breaks the rules of French heraldry with an incorrect superposition of colours (blue on red). While underscoring the weakness of the arguments in favour of the name Jean IV Le Viste as the patron of the tapestry, this new study suggests the probability of the intervention of Antoine II Le Viste, the descendant of the younger branch of the family, in ordering the Lady and the Unicorn. The incorrect superposition of colours could have been a deliberate choice intended to apprise the observer, in an explicit et well known manner, that he was faced with a familiar phenomenon, that of the modification of the coat of arms by a mark of cadency. Documentary sources appear to lend credence to this hypothesis

- ↑ "Medieval Mysteries: A Guide to History, Lore, Places and Symbolism: Karen Ralls PhD, p. 180: 9780892541720: Amazon.com: Books", Amazon.com, retrieved 1 January 2015

- ↑ Cavallo, Adolfo Salvatore. The Unicorn Tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York:Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998. pp. 99-100. Print.

- ↑ Masson, Sophie (October 19, 2016). "2BR02B: the journey of a dystopian film–an interview with Leon Coward". Feathers of the Firebird (Interview).

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Lady and the Unicorn. |

- The Unicorn

- Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries Musée du Moyen Age photos and discussions of the six tapestries. (Retrieved from the Internet Archive's copy on February 25, 2014)

- Mary Tudor - Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, the mysterious Lady of The Lady and the Unicorn ? http://dame-licorne.pagesperso-orange.fr/