Musée national du Moyen Âge

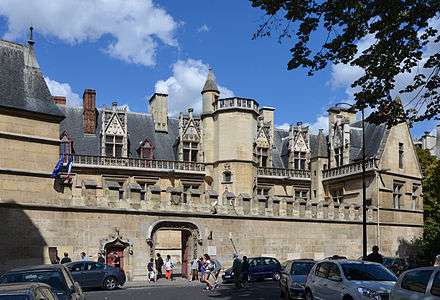

The Musée national du Moyen Âge, formerly Musée de Cluny (French pronunciation: [myze də klyni]), officially known as the Musée national du Moyen Âge – Thermes et hôtel de Cluny ("National Museum of the Middle Ages – Cluny thermal baths and mansion"), is a museum in Paris, France. It is located in the 5th arrondissement at 6 Place Paul-Painlevé, south of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, between the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Rue Saint-Jacques.

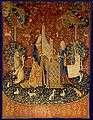

Among the principal holdings of the museum are the six The Lady and the Unicorn (La Dame à la licorne) tapestries.

The Hôtel de Cluny

The structure is perhaps the most outstanding example still extant of civic architecture in medieval Paris. It was formerly the town house (hôtel) of the abbots of Cluny, started in 1334. The structure was rebuilt by Jacques d'Amboise, abbot in commendam of Cluny 1485–1510; it combines Gothic and Renaissance elements. In 1843, it was made into a public museum, to hold relics of France's Gothic past preserved in the building by Alexandre du Sommerard.

Though it no longer possesses anything originally connected with the abbey of Cluny, the hôtel was at first part of a larger Cluniac complex that also included a building (no longer standing) for a religious college in the Place de la Sorbonne, just south of the present day Hôtel de Cluny along Boulevard Saint-Michel. Although originally intended for the use of the Cluny abbots, the residence was taken over by Jacques d'Amboise, Bishop of Clermont and Abbot of Jumièges, and rebuilt to its present form in the period of 1485-1500.[1] Occupants of the house over the years have included Mary Tudor, the sister of Henry VIII of England. She resided here in 1515 after the death of her husband Louis XII, whose successor, Francis I, kept her under surveillance, particularly to see if she was pregnant.[2] Seventeenth-century occupants included several papal nuncios, including Mazarin.[3]

In the 18th century, the tower of the Hôtel de Cluny was used as an observatory by the astronomer Charles Messier who, in 1771, published his observations in the landmark Messier catalog. In 1789, the hôtel was confiscated by the state, and for the next three decades served several functions. At one point, it was owned by a physician who used the magnificent Flamboyant chapel on the first floor as a dissection room.[4]

In 1833, Alexandre du Sommerard bought the Hôtel de Cluny and installed his large collection of medieval and Renaissance objects.[5] Upon his death in 1842, the collection was purchased by the state; the building was opened as a museum in 1843, with Sommerard's son serving as its first curator. The present-day gardens, opened in 1971, include a "forêt de la licorne" inspired by the tapestries.

The Hôtel de Cluny is partially constructed on the remnants of the third century Gallo-Roman baths (known as the Thermes de Cluny), famous in their own right, and which may be visited. In fact, the museum itself actually consists of two buildings: the frigidarium ("cooling room"), where the vestiges of the Thermes de Cluny are, and the Hôtel de Cluny itself, which houses its impressive collections.

The museum

The Musée de Cluny houses a variety of important medieval artifacts, in particular its tapestry collection, which includes the fifteenth century tapestry cycle La Dame à la Licorne.

Other notable works stored there include early medieval sculptures from the seventh and eighth centuries, and works of gold, ivory, antique furnishings, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts.

Gallery

Hôtel de Cluny

Interior of the Roman baths

Interior of the Roman baths- Element of the Pillar of the Boatmen, first quarter of the 1st century AD

Room of the Roman baths with capitals from the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Room of the Roman baths with capitals from the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés- View of the courtyard and its gallery

View of the courtyard and tower

View of the courtyard and tower- Tower door

- Gable window

The well

The well View from the medieval garden

View from the medieval garden View of the garden arcades

View of the garden arcades Capitals under the arcades

Capitals under the arcades Vaults of the gothic chapel

Vaults of the gothic chapel One of the rooms of the museum

One of the rooms of the museum A colourful stained glass room in the museum

A colourful stained glass room in the museum

Collections

- The Devil and a woman, stained glass, before 1248, from the Sainte-Chapelle

- Marble sculpture of the Presentation at the Temple, Burgundy, late 14th century

Reliquary of the Holy Umbilical Cord : Virgin and Child, gilded silver, France (Paris ?), 1407

Reliquary of the Holy Umbilical Cord : Virgin and Child, gilded silver, France (Paris ?), 1407 Casket : Apostles and angels, gilded champlevé enamel, Limoges, 2nd quarter of the 13th century

Casket : Apostles and angels, gilded champlevé enamel, Limoges, 2nd quarter of the 13th century Adam, stone, Paris, around 1260, from the interior of the south transept of Notre-Dame de Paris

Adam, stone, Paris, around 1260, from the interior of the south transept of Notre-Dame de Paris- Altarpiece of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, around 1250-1260, episodes of the life of Saint Benedict

- « Melancholic » Apostle, stone, around 1243-1248, from the interior decor of the Sainte-Chapelle

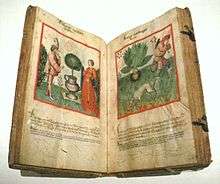

Health collection of Ibn Butlan, Rhineland, 2nd half of 15th century

Health collection of Ibn Butlan, Rhineland, 2nd half of 15th century- Visigothic votive crowns from the Treasure of Guarrazar, Spain, 7th century

Ivory binding of Ariadne with Maenad, Satyr and Cupids, Constantinople, 6th century

Ivory binding of Ariadne with Maenad, Satyr and Cupids, Constantinople, 6th century Ivory crosier, Virgin and child with two angels, around 1300

Ivory crosier, Virgin and child with two angels, around 1300 Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, A mon seul désir, late 15th century.

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, A mon seul désir, late 15th century. Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Hearing

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Hearing Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Taste, detail

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Taste, detail

References in literature

Herman Melville visited Paris in 1849, and the Hôtel de Cluny evidently fired his imagination. The structure figures prominently in Chapter 41 of Moby-Dick, when Ishmael, probing Ahab's "darker, deeper" motives, invokes the building as a symbol of man's noble but buried psyche.

In G. K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, the narrator states (chapter 13) that the wealthy Dr. Renard's rooms "were like the Musée de Cluny".

See also

Notes

References

- Seven Ages of Paris, Alistair Horne, (ISBN 1-4000-3446-9) 2004

- Michelin, the Green Guide: Paris, (ISBN 2060008735), 2001

- Album du Musée national du Moyen Âge, Thermes de Cluny, Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, Dany Sandron (ISBN 2-7118-2777-1).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hôtel de Cluny. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Musée national du Moyen Âge. |

Coordinates: 48°51′02″N 2°20′36″E / 48.85056°N 2.34333°E