Timeline of coelophysoid research

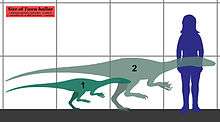

This timeline of coelophysoid research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the coelophysoids, a group of primitive theropod dinosaurs that were among Earth's dominant predators during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic epochs.[1] Although formally trained scientists didn't discover coelophysoid fossils until the late 19th century, Native Americans of the modern southwestern United States may have already encountered their fossils. Navajo creation mythology describes the early Earth as being inhabited by a variety of different kinds of monsters who hunted humans for food. These monsters were killed by storms and the heroic Monster Slayers, leaving behind their bones. As these tales were told in New Mexico not far from bonebeds of Coelophysis, this dinosaur's remains may have been among the fossil remains that inspired the story.[2]

The first scientifically documented coelophysoid taxon was Coelophysis bauri itself.[3] However, when the species was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1887, it was thought to belong to a genus of small carnivorous dinosaurs called Coelurus.[4] Later that same year Cope changed his mind and transferred it to the genus Tanystrophaeus. Tanystrophaeus turned out to be a long-necked reptile not regarded by scientists as a true dinosaur. As such, "Tanystrophaeus" bauri was soon given its own genus, Coelophysis in 1889.[5] Over the ensuing decades, many new coelophysoids would be discovered, like Podokesaurus, Procompsognathus, and Segisaurus.[3]

In 1947, a paleontological team led by Edwin Colbert made a major discovery in New Mexico. While on an expedition to Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, he made a detour to Ghost Ranch, New Mexico where many phytosaur fossils had been found.[6] There they discovered a massive bonebed preserving hundreds of Coelophysis, many of which were complete and articulated.[7] The find has been considered the most significant Triassic fossil discovery in North America.[8] Later, other coelophysoids and even other bonebeds would be discovered.[9] Notable coelophysoids discovered during the mid to late 20th century include Syntarsus (now Megapnosaurus) and Gojirasaurus.[3] Despite this extensive history of research, the formal recognition of the Coelophysoidea as a distinct group of dinosaurs is relatively recent and the group would not be formally named until a 1994 by Thomas Holtz.[10]

Prescientific

- Navajo creation mythology tells stories about the Grey Monsters that populated the world during earth's early days. These monsters came in a variety of forms, including flying and four-footed creatures.[2] They used to terrorize early humans, capturing them and cooking them, in the process leaving behind burnt places in the rocks near Taos, New Mexico. The Navajo believe that the Grey Monsters were wiped out by heroic Monster Slayers and storms. The remains of these monsters can now be found in stones, under tree roots, and near bodies of water. These stories were likely inspired by local fossils, including those of nearby Triassic amphibians and reptiles like Coelophysis, as well as the dinosaurs of the Jurassic Morrison Formation.[11]

19th century

1880s

- Othniel Charles Marsh named the Ceratosauria.[10] Coelophysoids would later come to be considered a member of this group for some time.[12]

- May 4th: Edward Drinker Cope described the new species Coelurus bauri.[4]

- Cope transferred Coelurus bauri to Tanystrophaeus bauri.[13]

- Cope described the new genus Coelophysis to house the species Tanystrophaeus bauri.[13]

1890s

- The American Museum of Natural History bought Cope's fossil collection and acquired the original Coelophysis type specimen.[14]

20th century

1910s

- Mignon Talbot described the new genus and species Podokesaurus holyokensis.[3]

- Fraas described the new genus and species Procompsognathus triassicus.[3]

- Von Huene published a detailed description and illustrated the fossils of Coelophysis for the first time in the scientific literature.[15]

1930s

- Huene described the new species Halticosaurus liliensternus.[3] He noted that at least two individuals of this species were preserved together.[16]

- Camp described the new genus and species Segisaurus halli.[3]

1940s

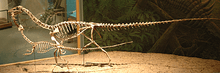

- While en route to collect fossils from Petrified Forest National Park, a team of paleontologists led by Edwin Colbert took a detour to Ghost Ranch, New Mexico where some interesting phytosaur remains had once been discovered.[6] While there they serendipitously discovered a bonebed preserving hundreds of Coelophysis, many of them complete and articulated.[7]

1960s

- Raath described the new genus and species Syntarsus rhodesiensis.[3]

1980s

- Welles described the new genus Liliensternus to house the species Halticosaurus liliensternus.[3]

- Rowe described the new species Syntarsus kayentakatae.[3] He reported that at least three individuals of this species were found preserved together in a single mass burial.[16]

- Colbert published his findings after 22 years of research on the Ghost Ranch Coelophysis bonebed.[17]

1990s

- Hunt and Lucas described the new genus Rioarribasaurus to house the species Coelophysis bauri. They also described the species Rioarribasaurus colberti.

- Cuny and Galton informally named the new species Liliensternus airelensis.[3]

- Holtz named the Coelophysoidea. He defined them as all theropods more closely related to Coelophysis than to Ceratosaurus. Within the Coelophysoids he defined the Coelophysids as the descendents of the most recent common ancestor shared by Coelophysis and Syntarsus.[10]

- Carpenter described the new genus and species Gojirasaurus quayi.[3]

- Hunt and others described the new genus and species Camposaurus arizonensis.[3]

- Sereno redefined Ceratosauria as all neotheropods closer to Coelophysis bauri than to birds. However, this definition never received broad acceptance by the scientific community because the Rowe had already defined the group in 1989, and therefore had priority. He also defined the Coelophysidae as the descendents of the most recent common ancestor shared by Coelophysis bauri and Procompsognathus triassicus. He further divided the family into two stem-based subfamilies; the Coelophysinae (all Coelophysids closer to Coelophysis than to Procompsognathus) and the Procompsognathinae (all coelophysids closer to Procompsognathus than Coelophysis).[10]

- Tykoski observed that since three species of coelophysoid had been recovered from the Kayenta Formation, this stratigraphic unit preserved the most diverse ceratosaur fauna known to science.[16]

21st century

2000s

- Ivie, Slipinsky, and Wegriznowicz described the new genus Megapnosaurus to house the species Syntarsus rhodesiensis.[3]

- Ezcurra and Cuny described the new genus Lophostropheus airelensis.[18]

- Nesbitt and others described the new genus and species Tawa hallae.[19]

2010s

- You and others described the new genus and species Panguraptor lufengensis.[20]

- Nesbitt and Ezcurra described the new genus and species Lepidus praecisio.[21]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Tykoski and Rowe (2004); "Introduction", page 47.

- 1 2 Mayor (2005); "The Monsters," pages 126–127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Tykoski and Rowe (2004); "Table 3.1: Ceratosauria", page 48.

- 1 2 Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," page 92.

- ↑ Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," pages 92–93.

- 1 2 Colbert (1995); "The Discovery," pages 1–4.

- 1 2 Colbert (1995); "The Discovery," pages 17–19.

- ↑ Colbert (1995); "The Discovery," page 20.

- ↑ Tykoski and Rowe (2004); "Paleobiology", pages 69–70.

- 1 2 3 4 Tykoski and Rowe (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 64.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "The Monsters," page 127.

- ↑ eg. Tykoski and Rowe (2004); in passim.

- 1 2 Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," page 93.

- ↑ Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," pages 93–94.

- ↑ Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," page 95.

- 1 2 3 Tykoski and Rowe (2004); "Paleobiology", page 69.

- ↑ Colbert (1995); "Bones and History," pages 96–97.

- ↑ Ezcurra and Cuny (2007); "Abstract," page 73.

- ↑ Nesbitt et al. (2009); "Abstract," page 1530.

- ↑ You et al. (2014); "Abstract," page 233.

- ↑ Nesbitt and Ezcurra (2015); "Systematic paleontology," page 515.

References

- Colbert, Edwin H. (1995). The Little Dinosaurs of Ghost Ranch. Columbia Univ Pr. ISBN 978-0-231-08236-5.

- Ezcurra, Martin D.; Cuny, Gilles (2007). "The coelophysoid Lophostropheus airelensis, gen. nov.: a review of the systematics of "Liliensternus" airelensis from the Triassic-Jurassic boundary outcrops of Normandy (France)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[73:TCLAGN]2.0.CO;2.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Nesbitt, S.J.; Ezcurra, M.D. (2015). "The early fossil record of dinosaurs in North America: A new neotheropod from the base of the Upper Triassic Dockum Group of Texas". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60. doi:10.4202/app.00143.2014.* Nesbitt, S. J.; Smith, N. D.; Irmis, R. B.; Turner, A. H.; Downs, A. & Norell, M. A. (2009), "A complete skeleton of a Late Triassic saurischian and the early evolution of dinosaurs" (PDF), Science, 326 (5959): 1530–1533, doi:10.1126/science.1180350, PMID 20007898

- Tykoski, R.S. & Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 47–70 ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- Hai-Lu You, Yoichi Azuma, Tao Wang, Ya-Ming Wang and Zhi-Ming Dong (2014). "The first well-preserved coelophysoid theropod dinosaur from Asia". Zootaxa. 3873 (3): 233–249. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3873.3.3.

External links

-

Media related to Coelophysoidea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coelophysoidea at Wikimedia Commons