Tlalocan

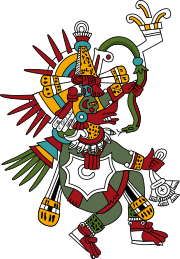

Tlālōcān [t͡ɬaːˈloːkaːn̥] ("place of Tlaloc") is described in several Aztec codices as a paradise, ruled over by the rain deity Tlaloc and his consort Chalchiuhtlicue. It absorbed those who died through drowning or lightning, or as a consequence of diseases associated with the rain deity. Tlalocan has also been recognized in certain wall paintings of the much earlier Teotihuacan culture. Among modern Nahua-speaking peoples of the Gulf Coast, Tlalocan survives as an all-encompassing concept embracing the subterranean world and its denizens.

Aztecs

In the Florentine Codex, a set of sixteenth-century volumes which form one of the prime sources of information about the beliefs and history of Postclassic central Mexico, Tlalocan is depicted as a realm of unending Springtime, with an abundance of green foliage and edible plants of the region.[1]

Tlalocan is also the first level of the upper worlds, or the Aztecs' Thirteen Heavens, that has four compartments according to the mythic cosmographies of the Nahuatl-speaking peoples of pre-Columbian central Mexico, noted particularly in Conquest-era accounts of Aztec mythology. To the Aztec there were thirteen levels of the Upper Worlds, and nine of the Underworld; in the conception of the Afterlife the manner of a person's death determined which of these layers would be their destination after dying. As the place of Tlaloc, 9th Lord of the Night,[2] Tlalocan was also reckoned as the 9th level of the Underworld, which in the interpretation by Eduard Seler was the uppermost underworld in the east.[3]

As a destination in the Afterlife, the levels of heaven were reserved mostly for those who had died violent deaths,[4] and Tlalocan was reserved for those who had drowned or had otherwise been killed by manifestations of water, such as by flood, by diseases associated with water, or in storms by strikes of lightning. It was also the destination after death for others considered to be in Tlaloc's charge, most notably the physically deformed.[5]

Contemporary Nahuas

In areas of contemporary Mexico, such as in the Sierra Norte de Puebla region, some communities continue to incorporate the concept of Tlalocán as a netherworld and shamanic destination in their modern religious practices.[6] As described by Knab, shamanic entry into Tlalocan, always achieved during dreams and often with the objective of curing a patient, is via underground waterways, commonly a whirlpool ("the water was whirling there and it took me in and down into the darkness around and around"[7]). Upon awakening, the shaman-dreamer will recount, to the audience during a curing-session, the itinerary traveled in Tlalocan; to which will be added (only when instructing a trainee or in speaking to other practicing shamans, never to an audience of general public) a description of the itinerary in term of numerically counted rivers, highways, and hills : as counted in series of 14, "There are thus thirteen of each type of feature located between the center and the edges of the underworld and one of each type (p. 120) of feature located in the center of the underworld."[8]

Here is a description of the sections of Tlalocan, as arranged in cardinal directions :-

- In the North "are the ehecatagat, the lord of the winds, and the miquitagat, the lord of death. They are the ones that care for souls for the first year after death. Both of the lords live in great caves. ... there are two caves, one on top of the other, and ... death lives in the lowest realm. The dead enter the underworld from the cemetery, where the lord death and his minions keep their souls. The role of the lord of the winds is to seek out more souls on the surface of the earth with which to populate the regions of the dead."

- "From the cave of the winds in the northern reaches of t[l]alocan issue the mal aires or evil winds, the feared ahmo cualli ehecat[l], the sombra de muerte or shadow of death, the miquicihual, and the miquiehecat[l], the nortes, 'the winds of death'."[9] "The cave of the winds ... is where the lord of the winds resides with his various assistants who guard the cooking pots ["According to numerous tales, the assistants are toads who keep the pots." (p. 163, n. 4:9)] where the ingredients for storms are kept, the winds, mists, rains, thunder, and lightning. Other assistants of the lord of winds are the quautiomeh or lightning bolts, the thunderclaps or popocameh, and the smoke ones, who make the miquipopoca or smoke of death that issues forth onto the surface of the earth, in t[l]alticpac, along with the winds of death."[10]

- In the South "is a spring of boiling water shrouded in mist and clouds. This spring is found in the depths of a cave illuminated by the fires of the popocameh. In the depths of this boiling spring, ... lives ... a giant worm, the cuiluhuexi.The cuiluhuexi eats the earth and fashions the caverns ... Its fiery breath and boiling saliva eat away the earth as it crawls beneath the surface."[11]

- In the East "is the place known as apan, the waters ... . Apan is a great lake or sea in the underworld that is united in its depths with all the waters of the surface of the world. In its depths live atagat and acihuat[l], the lord and lady of the waters. The acihuat[l] is often identified with the llorona or weeping woman {"in the Telleriano-Remensis and the Tonalamatl Aubin, her eyes are filled with tears"[12]} of folklore, who ... is always found near sources of water weeping”. ... In the depths of apan are cities ..., and ... souls – once they have passed out of the north at the end of the first year of death – seek out ... this region."[13]

- In the West "is actually a cave inhabited only by truly dangerous women such as miquicihuauh, 'death woman,' and the ehecacihuauh, 'wind woman.' " "the women from this side of the underworld ... went in search of the souls of men, especially lascivious men who couple with various women. They would also take the souls of women waiting on the paths, in the gardens, or in the fields for their illicit lovers."[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ As described in Miller and Taube (1993, p.167)

- ↑ Elizabeth Hill Boone : Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. U of TX Pr, Austin, 2007. pp. 95-99

- ↑ http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/america/am-moff4.htm (Fig. 1)

- ↑ Those dying of "natural causes", i.e. the majority, would instead endure a perilous journey through the layers of the Underworld to finally reach Mictlan, the lowest layer. See Miller and Taube (1993:178).

- ↑ See for example the Vaticanus A Codex, per Miller and Taube (op. cit.)

- ↑ See for example the investigations into religious practices of the area conducted by Timothy Knab, anthropologist at the Fundación Universidad de las Américas, Puebla, as recounted in Knab (2004).

- ↑ Knab, p. 69

- ↑ Knab, p. 119

- ↑ Knab, p. 107

- ↑ Knab, pp. 108-9

- ↑ Knab, pp. 109-10

- ↑ Elizabeth Hill Boone : Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. U of TX Pr, Austin, 2007. pp. 93b-94a

- ↑ Knab, pp. 110-1

- ↑ Knab, p. 112

References

- Knab, Timothy J. (2004). The Dialogue of Earth and Sky: Dreams, Souls, Curing and the Modern Aztec Underworld. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2413-0. OCLC 54844089.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.