Trochlear nerve

| Trochlear nerve | |

|---|---|

|

Path of the Trochlear nerve, right eye, superior view | |

|

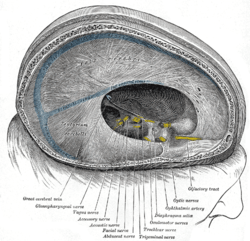

Inferior view of the human brain, with the cranial nerves labelled. | |

| Details | |

| Innervates | superior oblique muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus trochlearis |

| MeSH | A08.800.800.120.800 |

| TA | A14.2.01.011 |

| FMA | 50865 |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

The trochlear nerve,[help 1] also called the fourth cranial nerve or cranial nerve IV, is a motor nerve (a somatic efferent nerve) that innervates only a single muscle: the superior oblique muscle of the eye, which operates through the pulley-like trochlea.

The trochlear nerve is unique among the cranial nerves in several respects:

- It is the smallest nerve in terms of the number of axons it contains.

- It has the greatest intracranial length.

- It is the only cranial nerve that exits from the dorsal (rear) aspect of the brainstem.

- It innervates a muscle, Superior Oblique muscle, on the opposite side (contralateral) from its origin.

Homologous trochlear nerves are found in all jawed vertebrates. The unique features of the trochlear nerve, including its dorsal exit from the brainstem and its contralateral innervation, are seen in the primitive brains of sharks.[1]

The human trochlear nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic midbrain.

Structure

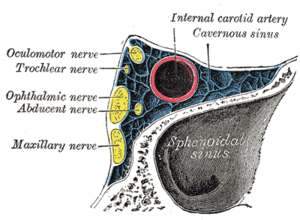

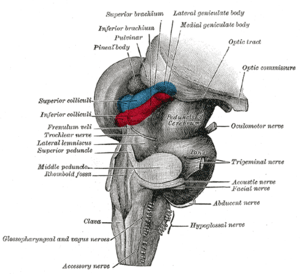

The trochlear nerve emerges from the dorsal aspect of the brainstem at the level of the caudal mesencephalon, just below the inferior colliculus. It circles anteriorly around the brainstem and runs forward toward the eye in the subarachnoid space. It passes between the posterior cerebral artery and the superior cerebellar artery, and then pierces the dura just under free margin of the tentorium cerebelli, close to the crossing of the attached margin of the tentorium and within millimeters of the posterior clinoid process.[2] It runs on the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus, where it is joined by the other two extraocular nerves (oculomotor - cranial nerve III and abducens - cranial nerve VI) and the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve (V), Ophthalmic (V1) and Maxillary (V2). The internal carotid artery also runs within the cavernous sinus. Finally, it enters the orbit through the superior orbital fissure and innervates the superior oblique muscle.

Nucleus

The nucleus of the trochlear nerve is located in the caudal mesencephalon beneath the cerebral aqueduct. It is immediately below the nucleus of the oculomotor nerve (III) in the rostral mesencephalon.

The trochlear nucleus is unique in that its axons run dorsally and cross the midline before emerging from the brainstem posteriorly. Thus a lesion of the trochlear nucleus affects the contralateral eye. Lesions of all other cranial nuclei affect the ipsilateral side.

Function

The trochlear nerve carries axons of type GSE, general somatic efferent, which innervate skeletal muscle of the superior oblique muscle.

The superior oblique muscle ends in a tendon that passes through a fibrous loop, the trochlea, located anteriorly on the medial aspect of the orbit. Trochlea means “pulley” in Latin; the fourth nerve is named after this structure.

Actions of the superior oblique muscle

In order to understand the actions of the superior oblique muscle, it is useful to imagine the eyeball as a sphere that is constrained – like the trackball of a computer mouse – in such a way that only certain rotational movements are possible. Allowable movements for the superior oblique are (1) rotation in a vertical plane – looking down and up (depression and elevation of the eyeball) and (2) rotation in the plane of the face (intorsion and extorsion of the eyeball).

The body of the superior oblique muscle is located behind the eyeball, but the tendon (which is redirected by the trochlea) approaches the eyeball from the front. The tendon attaches to the top (superior aspect) of the eyeball at an angle of 51 degrees with respect to the primary position of the eye (looking straight forward). The force of the tendon’s pull therefore has two components: a forward component that tends to pull the eyeball downward (depression), and a medial component that tends to rotate the top of the eyeball toward the nose (intorsion).

The relative strength of these two forces depends on which way the eye is looking. When the eye is adducted (looking toward the nose), the force of depression increases. When the eye is abducted (looking away from the nose), the force of intorsion increases, while the force of depression decreases. When the eye is in the primary position (looking straight ahead), contraction of the superior oblique produces depression and intorsion in roughly equal amounts.

To summarize, the actions of the superior oblique muscle are (1) depression of the eyeball, especially when the eye is adducted; and (2) intorsion of the eyeball, especially when the eye is abducted. The clinical consequences of weakness in the superior oblique (caused, for example, by fourth nerve palsies) are discussed below.

This summary of the superior oblique muscle describes its most important functions. However, it is an oversimplification of the actual situation. For example, the tendon of the superior oblique inserts behind the equator of the eyeball in the frontal plane, so contraction of the muscle also tends to abduct the eyeball (turn it outward). In fact, each of the six extraocular muscles exerts rotational forces in all three planes (elevation-depression, adduction-abduction, intorsion-extorsion) to varying degrees, depending on which way the eye is looking. The relative forces change every time the eyeball moves – every time the direction of gaze changes. The central control of this process, which involves the continuous, precise adjustment of forces on twelve different tendons in order to point both eyes in exactly the same direction, is truly remarkable.

The recent discovery of soft tissue pulleys in the orbit – similar to the trochlea, but anatomically more subtle and previously missed – has completely changed (and greatly simplified) our understanding of the actions of the extraocular muscles.[3] Perhaps the most important finding is that a 2-dimensional representation of the visual field is sufficient for most purposes.

Clinical significance

Vertical diplopia

Injury to the trochlear nerve cause weakness of downward eye movement with consequent vertical diplopia (double vision). The affected eye drifts upward relative to the normal eye, due to the unopposed actions of the remaining extraocular muscles. The patient sees two visual fields (one from each eye), separated vertically. To compensate for this, patients learn to tilt the head forward (tuck the chin in) in order to bring the fields back together – to fuse the two images into a single visual field. This accounts for the “dejected” appearance of patients with “pathetic nerve” palsies.

Torsional diplopia

Trochlear nerve palsy also affects torsion (rotation of the eyeball in the plane of the face). Torsion is a normal response to tilting the head sideways. The eyes automatically rotate in an equal and opposite direction, so that the orientation of the environment remains unchanged – vertical things remain vertical.

Weakness of intorsion results in torsional diplopia, in which two different visual fields, tilted with respect to each other, are seen at the same time. To compensate for this, patients with trochlear nerve palsies tilt their heads to the opposite side, in order to fuse the two images into a single visual field.

The characteristic appearance of patients with fourth nerve palsies (head tilted to one side, chin tucked in) suggests the diagnosis, but other causes must be ruled out. For example, torticollis can produce a similar appearance.

Causes

The clinical syndromes can originate from both peripheral and central lesions.

Peripheral lesion

A peripheral lesion is a damage to the bundle of nerves, in contrast to a central lesion, which is a damage to the trochlear nucleus. Acute symptoms are probably a result of a trauma or disease, while chronic symptoms probably are congenital.

Acute palsy

The most common cause of acute fourth nerve palsy is head trauma.[4] Even relatively minor trauma can transiently stretch the fourth nerve (by transiently displacing the brainstem relative to the posterior clinoid process). Patients with minor damage to the fourth nerve will complain of “blurry” vision. Patients with more extensive damage will notice frank diplopia and rotational (torsional) disturbances of the visual fields. The usual clinical course is complete recovery within weeks to months.

Isolated injury to the fourth nerve can be caused by any process that stretches or compresses the nerve. A generalized increase in intracranial pressure – hydrocephalus, pseudotumor cerebri, hemorrhage, edema – will affect the fourth nerve, but the abducens nerve (VI) is usually affected first (producing horizontal diplopia, not vertical diplopia). Infections (meningitis, herpes zoster), demyelination (multiple sclerosis), diabetic neuropathy and cavernous sinus disease can affect the fourth nerve, as can orbital tumors and Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. In general, these diseases affect other cranial nerves as well. Isolated damage to the fourth nerve is uncommon in these settings.

Chronic palsy

The most common cause of chronic fourth nerve palsy is a congenital defect, in which the development of the fourth nerve (or its nucleus) is abnormal or incomplete. Congenital defects may be noticed in childhood, but minor defects may not become evident until adult life, when compensatory mechanisms begin to fail. Congenital fourth nerve palsies are amenable to surgical treatment.

Central lesion

Central damage is a damage to the trochlear nucleus. It affects the contralateral eye. The nuclei of other cranial nerves generally affect ipsilateral structures (for example, the optic nerves - cranial nerves II - innervate both eyes).

The trochlear nucleus and its axons within the brainstem can be damaged by infarctions, hemorrhage, arteriovenous malformations, tumors and demyelination. Collateral damage to other structures will usually dominate the clinical picture.

The fourth nerve is one of the final common pathways for cortical systems that control eye movement in general. Cortical control of eye movement (saccades, smooth pursuit, accommodation) involves conjugate gaze, not unilateral eye movement.

Examination

The trochlear nerve is tested by examining the action of its muscle; the superior oblique. When acting on its own this muscle depresses and abducts the eyeball. However movements of the eye by the extraocular muscles are synergystic. Therefore one tests the trochlear nerve by asking the patient to look 'down and in' as the contribution of the superior oblique is greatest in this motion. Common activities requiring this type of convergent gaze are reading the newspaper and walking down stairs. Diplopia associated with these activities may be the initial symptom of a fourth nerve palsy.

Alfred Bielschowsky's head tilt test is a test for palsy of the superior oblique muscle caused by damage to cranial nerve IV (trochlear nerve).

See also

Notes

- ↑ The words trochlea and trochlear (/ˈtrɒkliə/, /ˈtrɒkliər/) come from Ancient Greek τροχιλέα trokhiléa, “pulley; block-and-tackle equipment”.

References

- ↑ Maisey JG. Morphology of the Braincase in the Broadnose Sevengill Shark Notorynchus (Elasombranchii, Hexanchiformes), Based on CT Scanning. American Museum Novitates, Number 3429. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 2004

- ↑ Bisaria KK. Cavernous portion of the trochlear nerve with special reference to its site of entrance. J. Anat. 159:29-35, 1988

- ↑ Demer JL. Pivotal Role of Orbital Connective Tissues in Binocular Alignment and Strabismus. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2004;45:729-738

- ↑ Hoya K, Kirino T. Traumatic Trochlear Nerve Palsy Following Minor Occipital Impact. Neurol Med Chir 40:358-360, 2000

Bibliography

Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. Sinauer Associates, 2002

Brodal A. Neurological Anatomy in Relation to Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 1981

Brodal P. The Central Nervous System, 3rded. Oxford University Press, 2004

Butler AB, Hodos W. Comparative Vertebrate Neuroanatomy, 2nd ed. Wiley-Interscience, 2005

Carpenter MB. Core Text of Neuroanatomy, 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins, 1991

Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2000

Martin JH. Neuroanatomy Text and Atlas, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2003

Patten J. Neurological Differential Diagnosis, 2nd ed. Springer, 1996

Ropper, AH, Brown RH. Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 8th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2005

Standring S (ed.) Gray’s Anatomy, 39th edition. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005

Wilson-Pauwels L, Akesson EJ, Stewart PA. Cranial Nerves: Anatomy and Clinical Comments. Decker, 1998

Additional images

Dura mater and its processes exposed by removing part of the right half of the skull, and the brain.

Dura mater and its processes exposed by removing part of the right half of the skull, and the brain. Hind- and mid-brains; postero-lateral view.

Hind- and mid-brains; postero-lateral view. Dissection showing origins of right ocular muscles, and nerves entering by the superior orbital fissure.

Dissection showing origins of right ocular muscles, and nerves entering by the superior orbital fissure. Upper part of medulla spinalis and hind- and mid-brains; posterior aspect, exposed in situ.

Upper part of medulla spinalis and hind- and mid-brains; posterior aspect, exposed in situ.- Trochlear nerve.Deep dissection.Superior view.

External links

- hier-449 at NeuroNames

- oph/697 at eMedicine - "Trochlear Nerve Palsy"

- MedEd at Loyola Grossanatomy/h_n/cn/cn1/cn4.htm

- lesson3 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (orbit2)

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (IV)

- Animations of extraocular cranial nerve and muscle function and damage (University of Liverpool)

- Trochlear nerve at Neurolex

- Notes on Trochlear Nerve