Tropical wave

Tropical waves, easterly waves, or tropical easterly waves, also known as African easterly waves in the Atlantic region, are a type of atmospheric trough, an elongated area of relatively low air pressure, oriented north to south, which moves from east to west across the tropics causing areas of cloudiness and thunderstorms. West-moving waves can also form from the tail end of frontal zones in the subtropics and tropics and may be referred to as easterly waves, but these waves are not properly called tropical waves; they are a form of inverted trough sharing many characteristics with fully tropical waves. All tropical waves form in the easterly flow along the equatorward side of the subtropical ridge or belt of high pressure which lies north and south of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Tropical waves are generally carried westward by the prevailing easterly winds along the tropics and subtropics near the equator. They can lead to the formation of tropical cyclones in the north Atlantic and eastern north Pacific basins. Tropical wave study is aided by Hovmöller diagrams, a graph of meteorological data.

Characteristics

A tropical wave normally follows an area of sinking, intensely dry air, blowing from the northeast. After the passage of the trough line, the wind veers southeast, the humidity abruptly rises, and the atmosphere destabilizes. This yields widespread showers and thunderstorms, sometimes severe. As the wave moves westward, the showers gradually diminish.

An exception to this rain is in the Atlantic. Sometimes, a surge of dry air called the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) follows a tropical wave, leaving cloudless skies, as convection is capped by the dry layer inversion. Also, any dust in the SAL reflects sunlight, cooling the air below it.

Atlantic

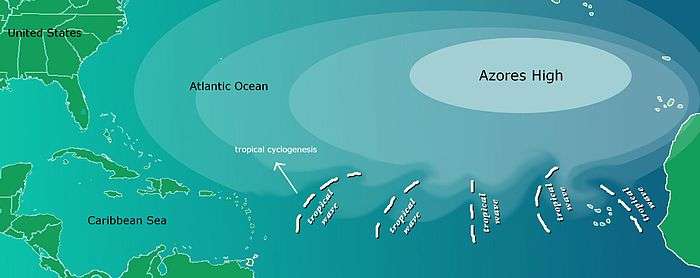

Tropical waves in the Atlantic basin develop from disturbances which develop as far east as Sudan in east Africa [1] and drift over the continent into the Atlantic ocean. These are generated or enhanced by the African Easterly Jet. The clockwise circulation of the large transoceanic high-pressure cell or anticyclone centered near the Azores islands (known as the Azores High) impels easterly waves away from the coastal areas of Africa towards North America.

Approximately 60% of Atlantic tropical cyclones originate from tropical waves, while approximately 85% of intense Atlantic hurricanes (Category 3 and greater) develop from tropical waves.[2][3]

Tropical cyclones can sometimes degenerate back into a tropical wave. This normally occurs if upper-level wind shear is too strong. The storm can redevelop if the upper level shear abates.

If a tropical wave is moving quickly, it can have strong winds of over tropical storm force, but is not considered a tropical storm unless it has a closed circulation. An example of this was Hurricane Claudette in 2003, where the original wave had winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) before developing a circulation.

East Pacific

It has been suggested that some eastern Pacific Ocean tropical cyclones are formed out of tropical easterly waves that originate in North Africa as well.[2] During the summer months, tropical waves can extend northward as far as the desert southwest of the United States, producing spells of intensified shower activity embedded within the prevailing monsoon regime.[4]

Screaming eagle waves

A screaming eagle is a tropical wave whose convective pattern loosely resembles the head of an eagle. This phenomenon is caused by shearing from either westerly winds aloft or strong easterly winds at the surface. These systems are typically located within 25 degrees latitude of the equator.[5] Rain showers and surface winds gusting to 29 mph (47 km/h) are associated with these waves. They move across the ocean at a rate of 15 mph (24 km/h). Strong thunderstorm activity can be associated with the features when located east of a tropical upper tropospheric trough.[6] The term was first publicly seen in an Air Force satellite interpretation handbook written by Hank Brandli in 1976. In 1969, Brandli discovered that a storm of this type threatened the original splashdown site for Apollo 11.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ "Morphed Integrated Microwave Imagery at CIMSS (MIMIC)". Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- 1 2 Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is an easterly wave?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion, Lixion A.; Richard Pasch (March 1995). "Atlantic tropical systems of 1993" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 123 (3): 887–896. Bibcode:1995MWRv..123..887A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<0887:ATSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ↑ Ladwig, William C.; Stensrud, David J. (2009). "Relationship Between Tropical Easterly Waves and Precipitation During the North American Monsoon". J. Clim. 22 (2): 258–271. Bibcode:2009JCli...22..258L. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2241.1.

- ↑ Bob Fett (2002-12-09). World Wind Regimes - Tropical Atlantic Screaming Eagle Tutorial (Report). Monterey, California: Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ↑ Henry W. Brandli (August 1976). AWS-TR-76-264 Satellite Meteorology. Air Weather Service. p. 101.

- ↑ Kara Peters. The Man Who Saved Apollo 11 (Report). Tufts Magazine Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

External links

- Tropical Waves Presentation

- African Easterly Wave Variability and Its Relationship to Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Activity